A new study, conducted by Dr. Miriam Larsen-Barr and a team of researchers, explored peoples experiences of attempting to discontinue antipsychotic medication. They investigated how people managed to navigate the process successfully and found that having support was a critical component to maintaining discontinuation.

“The qualitative data suggest that having support for attempted discontinuation provides a source of encouragement and hope alongside practical assistance with daily living, employing healthy coping strategies, and managing the reduction process,” Larsen-Barr writes.

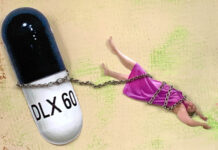

Data shows that most people who take antipsychotics attempt to discontinue them. The discontinuation process is accompanied by a variety of side effects including relapse of unwanted symptoms as well as cognitive, somatic, and emotional side effects. Much of the research on discontinuation focuses on clinical and medication factors. Less is known about how people manage attempts to stop and which factors influence their success in maintaining discontinuation.

Data shows that most people who take antipsychotics attempt to discontinue them. The discontinuation process is accompanied by a variety of side effects including relapse of unwanted symptoms as well as cognitive, somatic, and emotional side effects. Much of the research on discontinuation focuses on clinical and medication factors. Less is known about how people manage attempts to stop and which factors influence their success in maintaining discontinuation.

In this study, Drs. Larsen-Barr, Seymour, Read, and Gibson investigated how individuals navigate the discontinuation process with particular attention to the psychosocial factors, such as support and coping, that facilitate their success. To collect data, they drew from responses to The Experiences of Antipsychotic Medication Survey which was made available online for anonymous completion in 2014.

“This cross-sectional survey of 105 people’s most recent attempts to stop taking AMs [Antipsychotic Medication] represents only the third, and largest, study to date that specifically explores the way people manage attempted discontinuation of AMs, and how those efforts affect the success of their attempts.”

Participants included adults in New Zealand who had been on antipsychotic medication for at least three months and who were not currently in an inpatient unit. The overall sample of the study included 105 people who reported making at least one attempt to stop. They were asked questions about their experiences, including details about their last effort to stop, primary symptoms when the medication was first prescribed, withdrawal methods, coping efforts, and sources of support.

Some of these questions were formatted with open-ended responses allowing the researchers to analyze data qualitatively and quantitatively. Content analyses and deductive procedures were used to identify patterns and themes across responses. Researchers identified categories to describe the “coping strategies people used, the support they had for their attempt, withdrawal effects, experiences of relapse during withdrawal, and the subjective success of their attempt.”

Pearson’s Chi-square analyses were conducted to determine whether specific withdrawal methods, coping strategies, or social supports were associated with success in stopping and success in maintaining discontinuation.

Initial Success and Current Use

About half of the sample (50.5%) reported not taking antipsychotics at the time of the survey, and 55% reported having successfully stopped taking antipsychotics for varying periods of time. The majority of individuals (87.9%) who discontinued taking antipsychotics and had no current use had been off of them for over a year. About 38% reported last taking antipsychotics over five years ago. For the six individuals who reported stopping antipsychotics about six months prior, the authors noted that their chances of relapsing and resuming taking antipsychotics were high, based on the literature.

The qualitative responses by participants revealed that those who had successfully stopped taking antipsychotics at one point or another had resumed taking them because their alternative approaches were not sufficient.

The majority of people who were unsuccessful spoke specifically to their experiences of negative outcomes “such as hospitalizations, increased suicidality, disrupted employment and relationships, and compulsory treatment orders.” On the other hand, those who successfully stopped reported either noticing an improvement in their wellbeing or no change.

Experiences of Withdrawal

Many (61.9%) reported experiencing the full range of withdrawal effects including physical, emotional, cognitive, and functional setbacks. About 28% of the sample described a relapse of psychosis, mania, or hospitalization at the time of withdrawal. Others reported insomnia or disturbed sleep, or suicidal thoughts, urges or acts. Some reported experiencing short-lived effects, or no effects, and 13.3% reported having only positive responses to withdrawal.

The Availability of Support

Whereas about half of the sample described having some form of support in the form of at least one professional, family member, friend, or other social contact, the other half “reported feeling they had no support for their attempt; some kept their attempt a secret to avoid discouraging reactions from others or faced barriers to help-seeking.”

For those with support, the level of support varied, ranging from one to over three sources. These primarily consisted of family members and spouses, prescribers, friends and colleagues, professionals, peer support groups, and other forms of support.

Chi square tests found an association demonstrating that those who had support were more likely to describe successfully stopping and less likely to report current use. Additionally, people who had more support during their withdrawal were less likely to report experiencing relapses of psychosis or mania.

“In this group, discontinuation outcomes are also associated with having support for the attempt from other people. This suggests that overtly providing support to people who would like to stop AMs [Antipsychotic Medication] may improve their chances of success.”

Preparing to Stop and Intermittent use During Withdrawal

Almost half of the participants in the sample (48.5%) consulted with a doctor to prepare for discontinuation. However, consulting with a doctor was not significantly associated with success or current use, but it was associated with lower rates of relapse.

About one-third (32.4%) of responses indicated that antipsychotics were used intermittently to manage the effects of withdrawal. The use of antipsychotics in this way, however, was associated with less success withdrawing, greater chances of relapse, and a greater chance that the respondent was currently still taking antipsychotics.

Coping Strategies used During Withdrawal

Most participants (75.2%) provided the details of their coping strategies. This involved personal health-related or self-care strategies, medication strategies (e.g., using medicine to curb unwanted withdrawal effects), environmental strategies (e.g., avoiding stressful situations), and support strategies (e.g., utilizing social supports, therapists, or substances such as marijuana).

The results of this study highlight how social support can be instrumental to successful withdrawal, and that those who choose to keep this process completely private may be more susceptible to unsuccessful attempts or relapse. The researchers further highlight the importance of receiving encouragement and hope from an “advocate” rather than a “dispassionate observer.”

While the study is limited by featuring a nonrepresentative, namely one that was disproportionately New Zealand European, female, educated, and employed, responses nevertheless were novel in demonstrating a range of experiences and insightful associations.

The authors conclude with a strong statement supporting informed consent, and the right of individuals starting antipsychotic medications to be informed on their choices now and in the future:

“Given that it was possible for many to stop long-term (51% of the sample stopped for over 1 year) and maintain wellbeing without AMs, the current results strongly support the arguments made by other researchers, consumer rights legislation, and the service-user movement, that people should have the choice to take AMs or not take them, the choice to change their minds later, and all the information and resources required to make choices that are safe and have the best possible outcome for their recovery.”

They further elaborate that the paucity of information about these experiences poses practical and ethical risks:

“A lack of information about what is needed to safely manage withdrawal effects poses practical and ethical considerations for treatment systems aiming to align their practice with the principle of informed consent. It is difficult to freely choose to persist with AMs without knowledge of how to stop them.”

****

Larsen-Barr, M., Seymour, F., Read, J., & Gibson, K. (2018). Attempting to stop antipsychotic medication: success, supports, and efforts to cope. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 1-12.

42€ the paper… After, they ask why people read science on sci-hub.hk!

Report comment

Springer Nature have made a view-only copy of the full-text available here: https://rdcu.be/MpKs

Report comment

Informed consent, prior to prescribing antipsychotics, should include the fact that antipsychotics can create “psychosis,” via anticholinergic toxidrome. And that since this medically known, antipsychotic induced toxidrome is not a billable DSM disorder, it will always be misdiagnosed by the psychiatrists.

I do agree, it is unethical to prescribe any drugs, “without knowledge of how to stop them.” It’s also unethical to prescribe drugs to “cure” an unprovable “psychosis,” with drugs already medically known to create “psychosis.” And calling drugs that are known to create “psychosis,” “antipsychotics,” is also quite unethical.

Report comment

What are we talking about when we talk about not taking AMs?

There’s a big difference between taking say 450mg per day of thioradazine and taking 25mg per day of thioradazine.

450mg per day is likely to disable but 25mg per day would have a very mild anti anxiety effect.

Report comment

The lowest dose is what’s recommended and if this policy is followed the doses can be very unintrusive. But maybe doctors might be too hung up on diagnosis to allow “medication” to be reduced right down .

With me 25mg thioradazine per day eventually became nothing (- but even if it didn’t, it wouldn’t be doing too much harm).

Report comment