Researchers Drs. Joanna Moncrieff and Sandra Steingard critically examined two new studies that claimed taking antipsychotics continuously and indefinitely is the best approach for people diagnosed with first episode psychosis or schizophrenia. Their analysis, published in Psychological Medicine, suggests that such claims are misleading and unsupported.

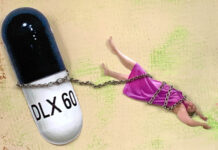

In a blog on the issue, Steingard writes, “there seems to be reasonable evidence that this assumption is not correct,” adding, “not only does long-term use of drugs expose people to the risks of weight gain and tardive dyskinesia, the drugs also impair functional outcomes.”

Together, Moncrieff and Steingard argue that “there is an insufficient appreciation of the potentially misleading nature of such analyses.”

Current guidelines, according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), recommend continued use of antipsychotics for at least one to two years for individuals who have experienced a single episode of psychosis. Moncrieff and Steingard point out that this is based upon the belief that if one remains well during this period, it may be safe to discontinue the drug.

However, two recent studies are challenging the reduction and discontinuation of antipsychotic drugs. These studies, closely examined by Moncrieff and Steingard, purport that long-term antipsychotic use ought to be the recommendation to most individuals who have experienced psychosis, even if it has only been in the context of a single episode. In this paper, Moncrieff and Steingard take a closer look at the claims drawn from these two studies.

The first study was a 10-year follow up of a randomized trial that compared antipsychotic drug, quetiapine and placebo maintenance. The original study was conducted by Dr. Hui and a team of researchers in Hong Kong. Before the 10-year follow-up was conducted, the relapse rates of the two groups from the original study were compared after two years. Relapse was defined “more liberally,” according to other researchers, note Moncrieff and Steingard. They found that those assigned to the quetiapine maintenance group showered lower rates of relapse and hospitalization at the one-year mark than those in the placebo group.

In the 10-year follow-up study, 142 of the 178 original participants were interviewed. Twenty-eight additional participants who could not be interviewed were analyzed with symptom measure data from the earlier study. They reported that 21% of the group members that were taking quetiapine had poor outcomes at the 10-year mark as compared to 39% of those with poor outcomes in the placebo group.

A closer analysis of this study demonstrates that “poor outcomes” were defined similarly to how “relapse” had been defined in that symptoms could be mild. Participants’ symptoms, suicide rates, and whether they were on Clozapine, another antipsychotic drug, were all observed to be correlated with outcomes. Moncrieff and Steingard reveal that most of the participants that were identified as having poor outcome met threshold scores on pre-specified psychotic symptom criteria—namely, delusions. Other outcomes, including other symptoms and work/social functioning, demonstrated no significant difference between the groups.

Moncrieff and Steingard write that “overall this study indicates that there was little difference in outcome between the groups 10 years after their enrolment in the antipsychotic discontinuation trial.”

They describe these results an unsurprising, given that the trial was shorter than its advertised 12-months (145 days for the quetiapine group and 106 for the placebo group) because of participant withdrawal and “relapse.” In addition to this, Moncrieff and Steingard address the implications of having used data from the original trial to assess the participants that were unaccounted for at the 10-year follow-up. They write:

“The inclusion of data from the original trial of some participants means the follow-up results do not reflect 10-year outcomes for all participants and means the results presented are likely to mirror the results of the original trial.”

The second study was a cohort study of observational, population data in Finland. The researchers had access to rates of death, hospitalization, and antipsychotic prescriptions. By examining rehospitalization rates and death, the researchers attempted to observe “treatment failure.” The primary results reported were that those who continue antipsychotic drugs were less likely to experience treatment failure than those who discontinued or who did not take them.

Moncrieff has written extensively about the limitations of this study in a recent MIA report. In their paper, Moncrieff and Steingard point out that these findings are difficult to interpret because not enough information is provided about the circumstances of death. Further, the study is observational in nature, meaning that the researchers did not control for certain factors. Causal inferences cannot be meaningfully derived.

The authors of the Finnish data study, according to Moncrieff, seem to take the argument across multiple studies that drugs are good for people’s health, despite the fact that many other studies demonstrate evidence to the contrary. In this particular study, the authors have been criticized for not including other factors in their observation such as socioeconomic status, substance misuse, and other health-related variables that are related to mortality.

Moncrieff and Steingard highlight that the researchers in this study excluded data recording deaths that occurred 24 hours prior to hospitalization. In addition to this, Moncrieff points out financial conflicts of interest between the authors and their “extensive links” with antipsychotic pharmaceutical companies.

What the data show, Moncrieff and Steingard argue, is that the rates of rehospitalization between continued and discontinued users of antipsychotics are actually comparable. The difference was that those who discontinued antipsychotics were readmitted earlier, but not more often than those who continued.

Moncrieff and Steingard write, “The result is consistent with other evidence showing that stopping antipsychotics brings forward risk of relapse but may not influence risk in the long-run.”

Moreover, it is important to recognize that people who discontinued from antipsychotic drugs may have done so without support or supervision. Discontinuing antipsychotics in a way that does not feature a controlled, gradual taper can be especially challenging and poses risks for readmission.

Overall, Moncrieff and Steingard emphasize that the observational data used to support long-term antipsychotic use is lacking and that contextual data are critical to interpreting and understanding the patterns presented. A closer examination of these studies reveals that they do not provide reliable data about antipsychotic discontinuation and further information is necessary to understand the benefits and risks of long-term use.

When asked for a follow-up comment about their critical review, Steingard shared:

“This commentary demonstrates the importance of reading beyond the headline or abstract on a study, especially when the studies are as complex as those reviewed here. For instance, how researchers define “relapse” will have major impacts on outcome. In headlines, it may conjure up an image that is quite different from how it was defined in the study. The can lead clinicians to make assumptions that are not well supported by the study data.”

Links to blogs:

https://www.madinamerica.com/2018/05/finnish-analysis-first-episode-schizophrenia/

****

Moncrieff, J., & Steingard, S. (2018). A critical analysis of recent data on the long-term outcome of antipsychotic treatment. Psychological Medicine 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718003811

I had an African friend who told me that his mother used to “go mad” from time to time, and recover again, and then go back to her job as teacher.

I think he also told me that in Africa “medication” was only used while people were in hospital (- and that this was why people were able recover).

(…I haven’t made this up, to score a point)

Report comment

The African friend didn’t realize that in the western world, health care refers to the financial health of upper level providers, pharmaceutical manufacturers, insurance companies, etc. If these individuals and groups are financially healthy, then we all allegedly become healthy just by contact with them, the way ancient Hebrews became cured of illnesses by touching Jesus’ garments.

Report comment

This is why the “antipsychotic” Clozapine is so highly recommended

https://amp.theguardian.com/society/2018/dec/22/clozapine-antipsychotic-implicated-in-two-deaths?CMP=share_btn_tw&__twitter_impression=true

Report comment

If my African friends sometimes “mad” mother lived in England 100 + years ago she might be described as “Hysterical”.

Today in England she might be described as “Schizophrenic”, put on “Clozapine” ….and never return to Teaching.

Report comment

Thanks for your work , Dr Moncrieff, and Dr Steingard. Coming from a now 50 year old , who was diagnosed/given the label of schizophrenia at age 19 and does not take “meds” or drugs. Intelligence and “good” behavior come from a fully functioning mind, not a drugged one.

Report comment

I would also like to thank Dr Moncrieff and Dr Steingard for their contribution.

Dr Rufus May and Author Will Hall (recovered “schizophrenics”) recommend similar straightforward Anxiety solutions for “schizophrenia” that actually work.

Recovery from Anxiety (/”schizophrenia”) is about practice not Neuro Science.

….And People don’t relapse with an effective psychotherapeutic solution.

Report comment

I think I need to read this a couple more times to truly understand all that’s trying to be stated, maybe that’s because of a couple glasses of wine during the holidays. Although maybe that’s because I tend to find medical literature to be particularly fact concealing and/or misleading, at least at times.

Nonetheless, this comment in you blog stuck out to me. “The result is consistent with other evidence showing that stopping antipsychotics brings forward risk of relapse but may not influence risk in the long-run.” My thought was that the term “risk of relapse” was likely misleading, since it is fairly well known that withdrawal from the neuroleptics can result in withdrawal effects, which are almost always misdiagnosed as a “relapse,” rather than as a withdrawal issue.

You do conclude by pointing out, “how researchers define ‘relapse’ will have major impacts on outcome,” which may relate to my concern that when doctors write in medical terminology, which has a lack of properly defined terms. This does lead to, intentionally or unintentionally, obfuscating literature. Have they defined “relapse,” and specifically and accurately delineated that from drug withdrawal? Just curious.

Nonetheless, Happy Holidays to all! And thanks to Drs. Moncrieff and Steingard for hopefully working to bring about the truth, some day … maybe … at least we can hope for the best.

Report comment

I’ve read a fair bit about these studies and it’s clear as mud and like all observational studies you make up your mind on something of a hunch. I have concluded that withdrawal hugely affects long term users because the risk of so called relapse goes up and up.

Unless you know the functioning of the group it’s difficult to figure out. I think there is an effect whereby you can be doped up but with less voice hearing and mediocre life quality, versus high functioning but perhaps subject to occasional wobble and certainly likely to wobble when withdrawing.

So, we don’t know for sure but some of us wonder why persistently clobbering your brain with antihistamines was ever a good idea, and if you hadn’t had that mistaken idea that controlling dopamine was the answer, would these drugs even exist.

And let us not forget that, amidst claims in the Hong Kong study that quetiapine halves your relapse risk, joanna Moncrieff has herself highlighted that this drug doesn’t really do what it’s supposed to anyway (because of low effect size). It’s so strange how drugs of questionable efficacy at all, all of a sudden become “relapse preventers”.

To me , the treatment model should be, get you through the crisis – somehow, maybe with drugs- and then ramp up the psychology and psycho social as fast as money can buy, so that you can keep yourself out of trouble , move forward and thrive.

Report comment

I wonder if tardive dyskinesia’s an important part of recovery from “mental illnesses” because it’s the most common obvious result of long term psychiatric drug therapy.

Report comment