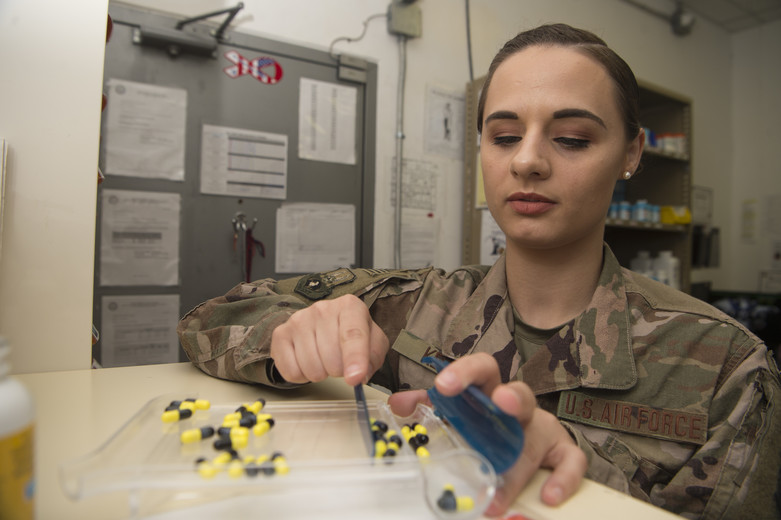

A new study, published in Medical Anthropology Quarterly, overviews a growing phenomenon in the U.S. military referred to as ‘pharmaceutical creep,’ where psychiatric drugs have become circulated throughout deployment zones with increasing regularity. This can range from the non-prescribed distribution of substances like stimulants to increase soldier performance to the prescription of antidepressants in ways that impede military objectives.

According to the author of the study, Dr. Jocelyn Lim Chua, an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of North Carolina:

“Psychopharmaceuticals variably drift, seep, infiltrate, deploy: They are smuggled into [deployment zones], flow in from civilian life, leak out of military supply chains, penetrate the military-corporate body, and are actively drawn into the tactical logic of urban counterinsurgency.”

“They engender anxieties and concerns for compromised soldier quality and effectiveness, even as they produce tactical opportunities and possibilities. They accrue multiple significations as they move, serving as ciphers of similarity and difference, affinity and disdain: at once the debased markers of civilian invasion, “routine” medication, contraband, and key technologies of global counterinsurgency.”

Historically, psy-professions like psychiatry and clinical psychology have shared ethically dubious relationships with the U.S. military. This was granted national attention in 2015 with the publication of the Hoffman Report. Here, it was revealed that members of the American Psychological Association (APA) had actively participated in the U.S. government’s “enhanced interrogation,” otherwise referred to as torture, programs at Guantanamo Bay and other overseas military detention centers.

While the APA council passed measures shortly thereafter to ban the participation of APA members in any such programs, renewed interest was sparked within and beyond the APA about psy-professions’ complicity in the U.S. military-industrial complex. Many psychologists expressed outraged about the history of torture and abuse that fellow members of the APA had participated in. However, others fought to cover up the revelations — or at least marginalize their significance in public discourse.

Today, one area where the relationship between psy-professions and the U.S. military is particularly evident is in the wide array of roles that psychopharmaceuticals serve in the everyday lives of deployed soldiers. As outlined in an article published in the New York Times, for instance, the number of psychotropic drugs prescribed for military personnel increased over 700% from 2005 to 2011.

According to Dr. Chua, the United States Department of Defense did not publish standards for the use of psychotropic drugs during deployments until 2006. This marked a stark contrast with the U.S. Army’s official position throughout the 1990s, which was that psychopharmacological treatments were largely unnecessary given soldiers’ supposedly innate abilities to heal themselves from the stressors of war.

Dr. Chua adds that most of the data collected on psychopharmaceutical use by military personnel have focused on periods before and after deployment. “Little is known about the use of different therapies for the management of mental and behavioral health conditions [in deployment zones] in the post-9/11 wars,” she explains, “and even less is known about the authorized and unauthorized use of psychopharmaceuticals for reasons beyond the treatment of these conditions.”

Going further, the author underscores how:

“Media accounts of soldier psychopharmaceutical use are often highly moralized: They frame the ‘drugging of our warriors’ as a sign of the biopolitical exploitation of soldiers, the inadequacy of the U.S. military‘s response to mental and behavioral health issues, and the failures of the post-9/11 U.S.-led military conflicts more broadly.”

“While such accounts commonly assume that military psychiatric medication use is for the purposes of medicating war and service-related trauma, in fact, there are multiple ways in which a single medication comes to matter to the U.S. military and to the soldiers who perform the work of violence while on them.”

To learn more about the unique ways that psychopharmaceuticals matter to the U.S. military today, Dr. Chua carried out a total of 18 months of ethnographic fieldwork at military bases across North Carolina, Washington, D.C., and Virginia. As of the publication of Dr. Chua’s paper, this research was still ongoing.

The research Dr. Chua conducted for the study included “36 semi-structured interviews with active-duty Army, Army National Guard, and Army Reserve enlisted soldiers, officers, and veterans who have deployed post-9/11 to either Iraq or Afghanistan and four interviews with military mental and behavioral health providers.” Beyond this, there were also four focus groups and a series of ethnographic observations at clinical trainings or military conferences where topics related to the use of psychopharmaceuticals within the U.S. military were discussed.

In the published study, Dr. Chua draws primarily on two case studies as examples of notably different trends of Psychopharmaceutical use in the military.

For “Luis,” a soldier deployed to Iraq from 2008 to 2009, a “steady flow” of Adderall directly from his sergeant kept him awake and alert during 18-hour long shifts, making his deployment “easy work” relative to other possible positions to which he might have otherwise been assigned.

According to Dr. Chua,

“The manner in which Luis‘s weekly Adderall escaped the military‘s regulatory mechanisms to transmute into something quite different in the context of counterinsurgency warfare recalls the diversion of high-dose buprenorphine from treatment contexts into informal networks . . . [whereby] two global addiction markets—one in which buprenorphine is valued as a pharmaceutical treatment tool and the other an illicit drug economy—merge through the process of what [Anne] Lovell calls ‘pharmaceutical leakage’.”

For “Matt,” a 13-year military veteran, however, active duty pharmaceutical use took on a very different meaning. While serving on what he describes as “a 12-man, self-sustaining, holistic unit that can go anywhere in the world and conduct operations,” he started to become concerned about the effects that prescribed antidepressants were having on two soldiers on his team.

While such pharmaceuticals were considered necessary for many soldiers to return to combat following earlier deployments, Matt cautions that, from his experience, they:

“completely change the person. Do they get them to calm down? Yes, but now they aren‘t as effective as they were before. These guys were only on them for 3, 4, 5 days. In my experience, that‘s about how long it takes for those drugs to kick in. Then they started to realize that they didn‘t have their edge anymore. So for example, there‘s a certain feeling and a sense when you know that things are going to go bad: I could feel IEDs, I could feel firefights before they ever came around. Certain smells. It‘s a whole world that changes. And they would lose that. So the answer was to not be on them anymore.”

As Dr. Chua notes, the two contrasting accounts of how psychopharmaceuticals are used within U.S. military deployments offered by Luis and Matt helps contextualize a set of problems that might otherwise be blamed simply on one institution or another. Instead, her research illustrates how pharmaceutical companies, psychiatrists, the medical field more broadly, the U.S. government, as well as individual soldiers and officers all play unique but highly interrelated roles in the phenomenon she describes as ‘pharmaceutical creep.’

Situating this within an even broader, historical context, Dr. Chua notes that the significantly lower number of psychopharmaceuticals used by U.S. soldiers prior to the publication of the 2006 handbook (referenced above) was partially a consequence of the long-term harm caused to soldiers who used medications like Compazine (prochlorperazine) and Thorazine (chlorpromazine) heavily during the Vietnam War.

And yet, “Sentiment began to shift in the mid-1990s with the development of ‘cleaner’ psychiatric drugs, namely SSRIs,” Dr. Chua explains. Adding:

“Drawing on her experience in peacekeeping operations in Somalia during the early 1990s, Army psychiatrist Elspeth Ritchie (1994) was the first to propose a ‘psychiatric sick call chest’ for both psychiatric emergencies and for chronic treatment of depression and anxiety. While those like Ritchie advocated for psychiatric medications to avoid damaging military careers with unnecessary removals from operational duty, skeptics warned that the safety of SSRIs in combat had not been proven.”

For Dr. Chua, this shift in attitude toward the use of psychiatric drugs in the military can be understood as a reflection of similar changes in perception that occurred in civilian life during the same period. Trends in psychopharmaceuticals becoming prescribed at much higher rates by non-psychiatric doctors, for instance, ‘crept’ into military contexts, creating a set of paradoxical tensions for military personnel like those illustrated by the stories above.

In the author’s words, “while the osmotic movement of psychopharmaceuticals into the space of theater [i.e., deployment zones] and into the military-corporate body is positioned as an inevitability of civilian overmedication, it flags the permeability—and questions the very future—of an institution whose purpose and coherence requires that it be a world set apart.”

The transdisciplinary nature of Dr. Chua’s research makes it uniquely situated to explore critical dimensions of psychiatry’s relationship to the military that are seldom discussed within either profession on their own. This is all the more important in light of the ongoing military efforts the U.S. has been engaged in since 9/11, or what Dr. Chua refers to as America’s “forever war.”

As she explains, this “reveals both tension and convergence in the space where global pharmaceuticals and U.S. empire meet.” With data collection and analysis still ongoing, the author of the study expects more light to be shed on these complex issues with future publications.

****

Chua, J. L. (2019). Pharmaceutical Creep: U.S. Military Power and the Global and Transnational Mobility of Psychopharmaceuticals. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12520 (Link)

Where’s the Speed? During the Vietnam war, methamphetamine was a must in Special Forces camps’ dispensaries. As it left them too wired to function in firefights, the Green Berets preferred to use them in poker games, to keep the players awake overnight, although card games for serious money in a weapon-filled team shack sounds too risky for me.

Report comment

Yes, 9/11/2001 marks the complete takeover of America by the wrong banksters, and their “omnipotent moral busy body” psychiatrists, who’ve been mass drugging our military.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5hfEBupAeo4

Although those psychiatrists have also been waging an, unmentioned in the mainstream media, internal war against all Americans who do not support “America’s ‘forever wars.'” Because the ethical, non-war mongering and profiteering, non-bailout needing, non-“banks stole $trillions worth of houses,” fiscally responsible American banking families are intelligent enough to know that “forever wars” will bankrupt America.

But the psychiatrists want to destroy the brains of all the American families who have multiple Phi Beta Kappa winners, who are “insightful,” and in general have common sense and high functioning brains.

Stop drugging our military, insane psychiatrists. You’re deluded about the effects of your “wonder drugs.” Your ADHD drugs and antidepressants create your “bipolar” symptoms. And your neuroleptics/antipsychotics create both the negative and positive symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome and anticholinergic toxidrome. Stop drugging our military.

Report comment

Thanks

https://www.google.com

Report comment

You don’t need to travel to war and occupation zones to see Lethal Psychiatric Drugs and Psychotherapy being used in the service of imperialism.

Just open your front door, go to prisons, salvation churches, and homeless encampments. You will see how Drugs, Therapy, Recovery, Motivationalism, and Salvation are used in the service of Capitalism, the Middle-Class Family, and the Self-Reliance / Self-Improvement Ethic.

Why Children Don’t Belong in Therapy — Daniel Macker

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TqvqLUSNv98

Report comment

Sadly, we have another article, and a series of accompanying comments that stir the hysteria. Comments such as “Lethal Psychiatric Drugs and Psychotherapy being used in the service of imperialism”, “But the psychiatrists want to destroy the brains of all the American families who have multiple Phi Beta Kappa winners”, do little to help and support the excellent work done the initiate the development of this website which justly earns my support. We all need to recognize there are misuses and there are mostly a lot of compassionate people that are doing the best they can with the tools they currently have. No, “ADHD drugs and antidepressants create your “bipolar” symptoms” as their are quite a few people without the drugs that have the symptoms. Read “Anatomy of an Epidemic” and note the alternative approaches developed in Finland that is now being practiced in some locales in the U.S. Change takes time and a reasonable approach. Hysteria and finger pointing add nothing.

Report comment

To be fair, the title of the article uses the word “imperialism”. It also goes a little into the relation between psychology and torture.

Report comment

“Sadly, we have another article, and a series of accompanying comments that stir the hysteria …do little to help and support the excellent work done the initiate the development of this website which justly earns my support.”

Eic, I don’t know much about you. You’ve only commented twice on this website that I can see. And I do agree with your other comment, treating withdrawal of the SSRI’s with the benzos is a really dumb idea. The videos I’ve watched, and what I’ve read, of the horrors of benzo withdrawal, are appalling. I’m guessing you’re a well meaning psychologist or mental health worker of some sort?

But I’ll point out that it’s also a really dumb idea to treat the withdrawal symptoms of the antidepressants with the antipsychotics. Since both drug classes are anticholinergic drug classes, and combining the anticholinergic drugs can cause anticholinergic toxidrome, which mimics the positive symptoms of “schizophrenia” to the “mental health professionals.” And such appalling maltreatment is the current “gold standard of care” for all “bipolar” stigmatized.

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/bipolar-disorder/expert-answers/bipolar-treatment/faq-20058042

I read “Anatomy of an Epidemic” long ago, it’s a book about the iatrogenic etiologies of our current “childhood bipolar epidemic.” It’s a book about how both the “ADHD drugs and antidepressants create your ‘bipolar’ symptoms.” So yes, such misdiagnoses, have led to the maltreatment of millions, which is now a societal problem.

And the psychiatric industries’ systemic malpractice is now at “holocaust” levels, they’ve been killing 500,000 elderly a year for decades.

https://www.naturalnews.com/049860_psych_drugs_medical_holocaust_Big_Pharma.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Eixy_rZHkE

I do agree, “the alternative approaches developed in Finland that is now being practiced in some locales in the U.S.” show promise. I agree, “Change takes time and a reasonable approach.” But I do not agree, the current DSM paradigm/recommendations are a “reasonable approach.” The current DSM paradigm/recommendations are a recipe for how the “mental health” industry may destroy all of Western civilization from within.

Thus, I believe “Hysteria and finger pointing” are needed, for actual change. I’m sorry it’s difficult for you to wake up to reality, but I hope you do so. The DSM was confessed to be “invalid” and “unreliable” by the head of NIMH six years ago.

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml

The DSM “bible” needs to be put to rest. Those who’ve used it to misdiagnose and harm others have been financially raping our entire country for their malpractice insurance to pay those they’ve harmed, and should use their malpractice insurance for what it is intended. And we need a return to the rule of law in our country, which psychiatry’s “reign of terror” eliminates.

Since the primary actual function of both the psychological and psychiatric industries, both historically and today, is covering up child abuse, which is a crime.

https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/01/23/18820633.php?fbclid=IwAR2-cgZPcEvbz7yFqMuUwneIuaqGleGiOzackY4N2sPeVXolwmEga5iKxdo

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

Report comment

This is an article that we’d expect on Mad in America. It seems to say a lot but ultimately doesn’t say much of anything that critizes the status quo. Or militarism. One look at the comment section though and you wonder what the posters read.

Curiously there’s not even a passing mention here about the number of military members who decided to kill themselves over the past decades even when psychiatric medications were dispensed more than ever. But “research” has discovered that being in the military or being in combat had little to do with their suicides. They were already likely or predisposed to do so. Accordingly, Dr. Chua wouldn’t dare bite a hand that feeds her by being (you know) critical of anything.

Report comment