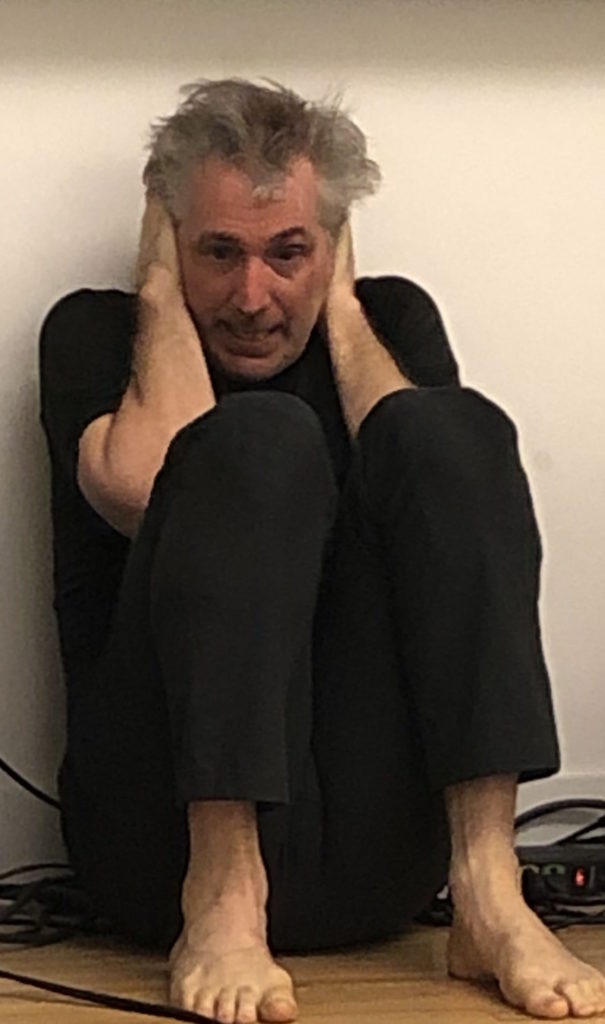

On the eighth floor of an old downtown Manhattan high-rise, NYU’s Create Lab is bustling with anticipatory energy prior to the 7:00PM performance of U.S. Army veteran Stephan Wolfert’s auto-biographical show Cry Havoc! Old friends greet each other while newcomers anxiously look around for a clue as to what they might expect out of the evening. It’s raining outside on this Monday night and a couple others quickly run in off the elevator and store their umbrellas. Stephan Wolfert, barefoot and a bundle of manic energy, is pacing frantically back and forth in this meeting room, a TV screen turned off in front, a clear glass wall looking out to the hallway. A few feet away from Stephan, a handful of veterans look around curiously as they wait for the show to begin.

Instead of starting the show right at 7:00PM, Stephan decides that he can’t begin without first connecting with everyone through a traditional group community circle.

“Everyone, let’s circle up. It feels weird if I don’t do it,” Stephan says. “Find your feet underneath your shoulder joints. Observe the good soldier stances around the room. Allow your belly to breathe. Check-in with yourself. Back to front, side to side. Let’s go around the circle . . . My name is . . . and right now I feel . . . ”

The group of ten begin to introduce themselves in the circle. This is not new to everyone; the returning group members are familiar with Stephan’s way of beginning evening meetings such as this. After the introductions, everyone begins to find their seats among the two rows of blue and green chairs facing the front of the room. Now they are more grounded and more connected than when first running in from the rain.

There are both military veterans and civilians here, and everyone leans intently forward. Stephan’s performance opens with the first line of Richard III:

“Now is the winter of our discontent . . .”

Normally, Monday nights at the Create Lab are filled with veterans, other than Stephan, rehearsing Shakespearean monologues. However, on this particular Monday, Stephan opened the doors to the public for a viewing of Cry Havoc!, his one-man show that showcases how the military characters of Shakespeare’s plays grappled with the same horrors and hopes as veterans do today. Richard III, he recalls, was a veteran of wars. After his riveting performance was over, Stephan briefly explained to the veterans that he created DE-CRUIT so they too could use the language of Shakespeare to tell their stories. “This is where you can find community to help you.”

DE-CRUIT—the name of the program tells of a need for veterans who were recruited into the world of the military and “wired up” for war, and now need to better understand the emotions roiling them as they re-enter the civilian world. The words of the great playwright are seen as a way to develop that understanding, and to help them rewire their brains for civilian life.

A Radical Departure from Conventional Care

There are now more than 2.7 million veterans of the military campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan. These campaigns have led to a surge in veterans who, in the language of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), have struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, addiction, and other emotional difficulties.

When their struggles are viewed through this lens, the trauma that veterans may have experienced—and the difficulties they may be having returning to civilian life—are identified as a “pathology” that resides within the individual. Although a veteran may be treated with psychotherapy and other non-drug treatments, the first line of treatment is psychiatric medication, with this often leading to veterans taking multiple psychiatric drugs at once.

If the suicide data for veterans is seen as a marker of the merits of that approach, there is evidence that it does more harm than good. Since 2001, more than 100,000 veterans have committed suicide. Moreover, a large VA study in 2016 found that those with a mental health/substance abuse diagnosis who got mental health treatment were 50% more likely to die by suicide than those with a similar diagnosis who did not access mental health treatment.

DE-CRUIT provides a radical alternative to that medical approach. Veterans are understood to be suffering from what might be described as a failure to re-integrate into civilian society. They come back from war and they feel they don’t fit in. They miss the camaraderie they experienced in the military. They find it difficult to relate to non-veterans who have no clue—or even curiosity—about what they may have experienced. They may become isolated, and when that happens, they begin to lack the confidence that is needed to get a job and prosper.

This is their problem in the 21st century. Yet, when they read and recite Shakespeare, they can see that the great 17th century playwright, in his descriptions of characters back from war, could be writing about them. Shakespeare’s characters too are buffeted by rages, insecurities, and an overwhelming feeling that they are different from all of the civilians around them. They have been changed by war.

This foray into the arts might seem to fall so outside of the medical realm that it would be difficult to assess its outcomes. Yet, research led by Alisha Ali is putting the program to the scientific test. She and her colleagues are finding that it produces a benefit in a variety of physical and psychological domains, providing evidence that DE-CRUIT both reduces the physical symptoms of stress/PTSD, and helps the veterans regain a sense of self, important to their getting work and “fitting” in with civilian society.

Discovering Shakespeare

Stephan Wolfert was born in the late 1960s, the youngest son of a working-class family. From a young age, while growing up in conservative La Crosse, Wisconsin, he was taught that honor came with a price. Often, he spent his days after school with his father at the neighborhood bar where he tried to remain as quiet and invisible as possible. Returning home with his drunk father, Stephan remembers the words that helped to shape him: “You won’t tell your mother we were here, right? You give your word of honor? Because once you give your word of honor, you’ve got to keep it.”

A victim of both sexual and physical abuse as a child, Stephan grew up dreaming of moving to New York City. He imagined how he could become a dancer after high school in order to escape the “asylum known as the Wolfert household.”

Before that became a possibility, he sustained a wrestling injury his freshman year of high school that resulted in paralysis from the navel down. While in rehab, Stephan was placed beside patients who had suffered from strokes. A seed was planted as he witnessed the possibility of the brain healing itself.

Remarkably, Stephan eventually made a full recovery and graduated high school. After a failed 18-month attempt to live at home because he couldn’t afford college, Stephan turned to the military.

After being turned away because of his high school wrestling injury, Stephan camped outside of the Army recruitment office in LaCrosse for a week. How long could they say no to him? He soon reported to Alabama for basic training.

Throughout basic training, Stephan was slowly trained and wired for war. He was, he says, trained to kill. Stephan didn’t imagine that he or his fellow soldiers would be vulnerable to deadly harm while stateside, but during a live-fire training exercise in Fort Irwin, California, Stephan’s best friend, Marcus, was hit by rogue ammunition. Stephan screamed for a MedEvac and rushed to hold his friend.

“His head was like an over-inflated water balloon, being held together by my hands,” Stephan recalls.

He was able to keep his grief at bay just long enough to hand a folded flag to Marcus’s widow and his two baby girls. Then, he fell apart and his grief knew no bounds. One night—and this was seven years after he had joined the military—Stephan found himself driving aimlessly around rural Montana, drunk and suicidal.

And that was when he stumbled upon a local performance of Richard III.

“I sat transfixed sitting in the audience [of Richard III],” he says, as he performs Cry Havoc! “And yet there I stood on stage, like me, a soldier. Hearing the poetry, feeling this rhythm in my body. Seeing a veteran on stage express exactly how I felt without even realizing.”

After that night, Stephan began fervently researching other Shakespeare plays and monologues. Was the familiarity he felt while watching Richard III a fluke? Or could he find this same sense of personal recognition in other Shakespearean works?

He discovered that “among the characters in Shakespeare’s plays, there are numerous veterans who astutely describe their military trauma.” Their words, written centuries earlier, “described perfectly the vet experience and PTSD.”

Soon Stephan resigned his commission with the US Army. In 1997, he enrolled in the Trinity Repertory Conservatory to pursue acting. Stephan was the only veteran in his program, and he could see that he was different from his civilian classmates. “I responded differently if a helicopter flew overhead, I stood transfixed, unable to focus on anything else,” he says. “I responded in anger if I heard a sound that I was not expecting.”

Stephan continued to have difficulty adjusting to civilian life. He may have discovered Shakespeare, but his past still had a hold on him. Without a unit to report to, he had lost his sense of duty. What remained was the deep effects of the trauma he had experienced in the military.

And so he drank. He drank to self-medicate. But drinking couldn’t remove the wiring for war that had been instilled in him through his military service. In Cry Havoc!, he tells of his despair and of a moment that brought him to his knees.

These gorgeous little four-, five-, and six-year-old girls are dressed in their Disney princess gowns and my job as a caterer is to bend over and pick up these saliva-strewn balls. And as I bent over to pick one up, I saw my hand as it was when I served in the military. I saw the dirt and gun oil actually in the cracks of my hands, and I blinked and it was gone and I saw what I was doing. These hands that served this country, that held my best friend’s head together, handed several folded flags to weeping family members, called in air strikes, MedEvacs, saluted people that were calling me sir and looking me in the eyes, and now I’m picking up… And as I knelt there for I don’t know how long… I might have been kneeling for three-tenths of a second, three minutes, I have no idea.

A little girl walked up, looked me right in the eyes. The first one all day to look me in the eyes and she threw her cake at me. And my body’s reaction, not my thought, my body’s impulse, was to crush her skull. I lurched at her, caught myself. I didn’t hit her. I caught myself. We locked eyes, horrified. She turned, ran screaming to her mother. More horrified I pulled myself up, ran to my Jeep in the parking ramp, drove home to my apartment in Venice, locked the door, pulled out my sawed-off shotgun, opened up the breach, jammed a shell in, closed the breach, and rocked back the hammer . . .

“What is wrong with me?” Stephan asked himself. That was the question that haunted him, and it led Stephan on a journey to better understand his own trauma, his craft, and to create DE-CRUIT.

DE-CRUIT Takes Flight

The path to DE-CRUIT was a lengthy one. The seed for it, Stephan explains, had been planted during his time in graduate school. Despite his difficulties, he had nevertheless begun to appreciate that his training as a classical actor was helping him regain some measure of control over his emotions and thoughts. And so the light bulb went off: If theater could be his medicine, might it help others as well?

After graduating, Stephan began working with Twyla Tharp, the renowned American dancer and choreographer. She told him that his fellow dancers, since they were kids, had been wired to stand like dancers. However, he had been wired in the military to stand like a soldier. “Working as an artist gave me the understanding that soldiers are similarly wired, but wired instead for war,” Stephan says.

In 2003, Stephan moved to Los Angeles to be mentored by Randy Reinholz, the founder of Native Voices. This group focuses on the story-telling of Native Americans, which, Stephan recalls, helped him to “embrace theater as medicine instead of being afraid of it. I knew it was what I wanted once I worked with them and experienced it for myself.”

Piece by piece, he was discovering the healing touch of theater, and seeing it as a process that could help many. Actors must learn to control their breathing, and this led him to see that he could regulate and ground himself through his performances.

In addition to his work with Native Voices, Stephan became the founding artistic director of the Veterans Center for the Performing Arts in Los Angeles. During his seven years there, he both developed and produced original works by veterans for the stage, and he examined existing works from a veteran’s perspective.

All of this was coming together into a larger vision. He had come to appreciate the way a soldier had been wired for war; he had experienced the healing touch of theater; and now, in his work with other veterans, he was finding that “narrative therapy”—the telling of one’s own story—could have a powerful impact too. And ultimately, he understood this: he had been “using Shakespeare to rewire [his own] brain.”

And now he had his answer to the question he asked so many years earlier.

“What is wrong with me is what happened to me . . . I and my brothers and sisters who were recruited or drafted were done so at a psychologically malleable age and then we were wired for war. But we were never unwired from war after our service. We were not rewired for society.”

And thus DE-CRUIT was born: “If we had a recruiter to prepare recruits for anything that might happen in the military—where was the decruiter? We don’t have one in this country, so I made one.”

With this new dream in mind, Stephan moved to Brooklyn in 2013 to look for other people who could help him study the connection between Shakespeare and the science of healing. At the same time, he developed Cry Havoc! as an off-Broadway show which served as his own version of DE-CRUIT narrative therapy.

In 2014, Stephan found the people he was looking for. Through the Project for the Advancement of Our Common Humanity, a social justice think tank, he connected with a New York University research team, led by Alisha Ali, an associate professor in applied psychology. The NYU-based think tank aims to bring together health professionals, artists, activists, and researchers to better understand the role of arts and community in addressing mental health. Stephan credits Ali with being the first person who actually took the time to listen and understand his vision for an alternative therapeutic treatment approach such as DE-CRUIT.

DE-CRUIT as a Therapy

PTSD is typically treated through traditional psychotherapy, prolonged exposure, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), and psychiatric drugs. Yet, suicide rates among veterans diagnosed with PTSD and treated in this way are high; up to 68% of veterans drop out of clinical treatment for post-traumatic stress, and the reliance on psychiatric drugs has led many to become dependent on these medications.

The rates of unemployment and homelessness are also markedly high among veterans. Both Wolfert and Ali argue that these problems “can be understood as manifestations of our society’s failure to respond adequately to the needs of veterans when they return from service.”

As Wolfert designed the DE-CRUIT program, with support from Ali and others, he constantly focused on this question: What did veterans say they needed? They told of three overarching needs:

- “I need to get a job.”

- “I need to relate to people around me.”

- “I need community.”

All of this told of a struggle to re-integrate into civilian life. While conventional treatments for PTSD seek to reduce the symptoms of PTSD, DE-CRUIT was based on the understanding that the veterans needed to develop skills that would help them find meaningful work and better relate to others, and find a community. The problem wasn’t solely within them; it resided in their relationship to the civilian world.

In contrast to existing forms of treatment, Wolfert and Ali write, DE-CRUIT “adopts an approach that is strengths-based in its orientation toward fostering post-traumatic growth, as well as veteran-informed in its use of military derived concepts that are positively framed through theater to foster therapeutic camaraderie among group members.”

The veterans entering DE-CRUIT begin by watching Wolfert’s one-person play Cry Havoc!, either live or via video. Then, as a group, they go through a program that is a “fully manualized eight-week treatment,” with the group meeting once a week.

The treatment sessions are closed to the public. The veterans start each session in a circle to “ground themselves to the present moment and to those around them.” The circle ritual is taken from Stephan’s work with Native Voices and is meant to communalize the experience, encourage the participants to be bold, and to dare to fail.

The treatment then unfolds in five stages.

In the first stage, the group joins together in “entering the world of Shakespeare’s verse.” Together, they learn to recite verses from Shakespeare that tell so poignantly of the scars that come from war.

Next, each veteran writes his or her own personal “trauma monologue.” In addition, the veterans are given a piece of paper filled with words that describe experiences soldiers typically face, and they are then asked to circle the words that “hold emotions” for them. In this way, veterans begin to identify the themes from their narrative and from the circled words that will help them find an appropriate Shakespeare monologue to eventually perform.

It took Ali, Wolfert and others years to develop a method for matching themes from the personal stories to monologues in Shakespeare. After carefully observing and recording the themes that regularly surfaced with veterans, they created an algorithm for making this match. “We now can categorize the themes like insomnia, moral injury, sense of betrayal, etc., and in those categories there are monologues from Shakespeare that fit within that,” Ali says. “For example, someone with recurring nightmares might be given Richard III or the infamous “Out, Damned Spot” monologue of Lady Macbeth.

In the third stage, each veteran hands off his or her personal trauma monologue to a fellow veteran, who then rehearses and performs that monologue. The veteran now gains an “aesthetic distance” from his or her own trauma, and from that distance, can now feel empathy toward the veteran performing the monologue. For veterans who are unable to forgive themselves for some wartime trauma, such as the death of a fellow soldier, this distance can provide the veteran with a new self-awareness and a path to self-forgiveness.

In the fourth stage, the veterans go through the physical training necessary to deliver their Shakespearean monologue. Many such monologues are told in iambic pentameter, and the veteran needs to focus on breath control to deliver the lines. The beat in Shakespeare’s verse echoes the rhythm of the human heart and this practice has been found helpful in reducing their “heart rate variability.” A reduction in this variability is known to “track well-being,” researchers have found, and thus this breathing exercise, wrapped within an actor’s training, is reducing the stress response that is a key component of PTSD.

As might be expected, the final stage is a public performance. The veterans perform both their own personal trauma monologue and their Shakespearean monologue before an invited audience of fellow veterans, family members, friends and other community members.

By this time, the group has formed a deep bond, they have felt the strength of being part of a community, and now each veteran must confront the “risk” that comes with a public performance. And as any stage actor can attest, the aftermath of a public performance provides an actor with a sense of accomplishment and competence, and the joy of having done so as part of a troop.

In psychological terms, this public performance provides for a “communalization of trauma,” which has been identified “as crucial to the healing of trauma for military veterans,” Wolfert and Ali write. “The audience bears witness to the veterans’ pain, the fellow veterans in the group support each other through the performance and through the articulation of personal suffering, and together the entire group contributes to the process of sharing, feeling, and healing.”

The Science of DE-CRUIT

Ali began her research on trauma and stress in the 1980s, which was shortly after PTSD was categorized as a distinct disorder in the third edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The diagnoses in this manual were presented as medical disorders, and thus it became the norm to treat PTSD with antidepressants and other drugs.

As a result, today there are many veterans who come to DE-CRUIT with a “bin of pills because they are told that is what they need to get through the day,” Ali notes. “We say, ‘let’s see what you can do to bring out your inner resources to help you’.”

In the medical environment, research on a treatment for PTSD focuses on the reduction of the symptoms of the disorder. Ali and her colleagues, in their research on the DE-CRUIT outcomes, need to assess that symptom element and more: Does DE-CRUIT help veterans gain self-confidence? Does it help them feel better understood by the community? Does it provide them with a new way to “imagine” their own traumas?

When she started, PTSD researchers were not much focused on questions like these. But that is changing for two reasons, she says.

“One: There is a growing skepticism of the pharmaceutical industry. The opioid crisis has really brought to light the complicity of the industry in growing the epidemic of addiction. Two: Scientists are no longer seen as being at odds with physicians. We are coming towards a common understanding of alternative treatment methods and are saying that maybe there are things that can truly help.”

Ali’s research on DE-CRUIT “outcomes” is still in a preliminary phase. However, she and her colleagues have found that it produces these beneficial effects:

- It “significantly reduces symptoms of post-traumatic stress and depression.”

- It produces “significant increases in self-efficacy,” which means participants gain a greater belief in their own “abilities and competencies.” This translates into an increased confidence that they can get a job, socialize well with others, and so forth. This is a measurement showing that the treatment is helping provide the veterans with the confidence necessary to take their place in civilian society.

- As noted above, it produces significant improvements in heart-rate variabilities.

- It significantly improves “EEG function” which is a measurement associated with improved brain function.

The veterans also stay in this treatment: fewer than 10% who enter the program drop out before completing it.

Ali says that programs like DE-CRUIT are not necessarily intended to replace traditional medical treatments. “These sorts of arts-based approaches have to be part of the offerings for those with trauma. They need to be situated right alongside the current ‘tried and true’ methods, especially because [those methods] don’t produce the type of results we thought they did. We need to look at the data and see what it tells us [about arts-based therapies like DE-CRUIT] and have true evidence-based treatment.”

As the DE-CRUIT community continues to grow, so too do the lessons learned. When asked what lies ahead for DE-CRUIT, Ali first reflected on some of the discoveries borne from DE-CRUIT’s growth. “We learned that the trauma experienced is not categorically different from so many marginalized and oppressed people in society. They are different points on the same continuum.”

Additionally, so often the traumas that veterans unpack are actually focused on their early childhood. In fact, Wolfert and Alisha “have learned that trauma occurring earlier in life can both precipitate the decision to join the military (e.g., as a means of escaping an unsafe or abusive home environment) and also cultivate a need for some of the central elements of military training (e.g., building physical strength, learning to protect oneself and feeling a sense of belonging and camaraderie).”

This is certainly true in Wolfert’s own performance of Cry Havoc! where so much of his performance comes back to his early life. Recently, it was this particular lesson that has served as a catalyst for Ali and Wolfert to realize that “there is something about this method that is not just specific for vets.”

DE-CRUIT is now being designed for use in both a local New York City high school as well as in New York’s Rikers Correctional Facility, for both correctional officers and inmates. Wolfert’s guiding message holds true irrespective of where and how your trauma occurred. “It doesn’t matter if your trauma happened before, during, or after the military. We are here for you.”

One Vet’s Experience

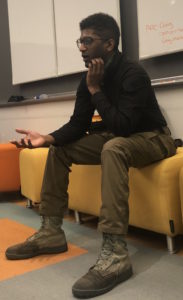

Craig Manbauman is a first-generation American from Jamaica who turned to the military in search of a reset after a rocky start at Queens College. Craig said that he “felt that the odds were against him financially and he desired to do something greater than ever before.” He stood resolute even after his friends tried to dissuade him from joining the Air Force. The perception of his friends was that “you only join the military if you aren’t intelligent enough” and he sought to fight against that stereotype.

Craig thrived in the military environment of brotherhood and camaraderie. He identified himself as a natural caretaker, finding meaning in a medical position that required him to tend to the wounds of his military brothers.

However, starting in basic training, Craig understood that he had to forego his civilian “wiring” for the wiring of a soldier. Drill sergeants constantly watched Craig and the new recruits, walking past to inspect and intimidate each soldier. They were being taught to “always be vigilant,” Craig says. “A lot of self-policing was sown into who they make you to be.”

During basic training, Craig learned to embrace rigidity and structure. He eventually moved to Wright-Patterson Air Force base in Ohio in order to complete EMT practical training. There, Craig experienced death for the first time. Sirens blared and flashed red as Craig was working in the emergency room one late evening, and he was soon directed to start compressions on a veteran suffering from cardiac arrest. Within minutes, however, the veteran died and Craig was left standing there feeling lifeless himself. From down the stark white halls, Craig saw his own sergeant break down in tears. Craig didn’t know how to react. A man devoted to his brotherhood, Craig internalized that he was the one who had not done enough. He vowed to never have to experience that feeling of inadequacy again.

Unfortunately, Craig would have to break that vow over and over again as he witnessed more and more lives lost throughout his medic training. Craig constantly strove to improve his abilities, but he always felt like he came up short and couldn’t honor the vow he made to himself. Eventually, he found himself at a crossroads. Years into his training and service, he still did not have a degree and he felt he lacked the depth of medical training necessary to help his brothers and sisters. He began to feel the emotional, physical, and mental fatigue that came with military life.

After four years in the Air Force, Craig applied and was accepted to the Palace Chase Program, which allowed him to trade in active duty time for reserve time and return to school. “There was a lot of good in the military, but I overall felt dissatisfied,” Craig says. “I wanted more intellectual stimulation and there was a lot of turmoil at home.”

Craig went to Long Island University Brooklyn to pursue his degree and be close enough to care for his younger brother. After not finding a veteran community on campus, Craig decided to form a veteran-student organization himself. “The military for all its good and bad is a supportive structure. You never have to feel alone in anything you are doing.”

This desire for support and community eventually led Craig to DE-CRUIT in 2018. He immediately understood the concept: this would help him “unwire” from his military days, and yet the process would involve using the same techniques that the military had used to wire his brain. However, as Craig first began to integrate himself with the others in his DE-CRUIT group, he felt a growing insecurity mounting within him. Did he deserve to be among other veterans who had served multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan? Did his military wiring and trauma even matter in comparison to that of his peers? Did the fact that he helped traumatized veterans with severe battle injuries during his deployment window instead of going abroad make him less acceptable to the others?

Craig soon found that his fears were unfounded. As he and the other veterans spoke about the experiences that had impacted them the most, he felt the stirring of relationships and bonds that would carry through the eight-week program.

Stephan, he says, never spoke about any “obligation to know Shakespeare.” Instead, he told Craig and the others to “make yourself present for the words and dare to be wrong.”

After each of the veterans wrote their own personal narrative, Stephan asked each one to step forward and read one of Shakespeare’s monologues. All the others, gathered in a circle, would fall silent and listen intently.

“One of the things that Stephan always reinforced was claiming time and space as your own,” he says. “Standing up in a room, trying not to rush through your piece, your breath all of the sudden becomes so important. The way Shakespeare is written forces you to take grounding breaths. If someone was reading something very difficult, the class supports you through it. The group is invited to lift you up and support you. You know that if and when the time comes and you need that support too, everyone will be there.”

During the weeknight DE-CRUIT session I attended, Craig told the others how it was the “DE-CRUITer breath that had helped him to stay grounded and calm after he had a small accident in a car.”

Responded Stephan: “Being present is what trauma robs us of, and that is what the military, to a certain extent, robs us of too. If you begin to feel like you are dissociating, your breath will bring you right back.”

As he proceeded through the training, Craig found that it was the communal aspect that was most helpful to him. “Although some traumas happen in isolation, to think that the healing must happen in isolation is a fallacy,” he says. “You need that societal space for healing and validation, to see you through it and know that you are supported.”

Even after he completed the DE-CRUIT program, Craig continued to come back to the NYU CREATE lab for informal DE-CRUIT community session. And since Stephan and his wife Dawn now spend much of their time now traveling around the country in a van to perform Cry Havoc! and speaking about DE-CRUIT at conferences on trauma, Craig regularly manages the weekly DE-CRUIT classes in New York and serves as the New York DE-CRUIT manager.

“A lot of good things are happening in my life right now,” he says. “I feel loved and supported. I feel like I have the skills necessary to achieve my goals. DE-CRUIT gives me the tools to sustain myself mentally and emotionally.”

However, on this rainy Monday night, Stephan is leading the group. As the meeting ends, the group of ten again comes together in a circle and Stephan asks everyone to make eye contact with everyone else in the circle. “Know that this is the group of people that you can think about this week if we start to feel lost or lonely. Whatever it is. Remember these beautiful, brave faces.”

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

I don’t know about this. As a former 11 bangbang with a Combat Idiot’s Badge (the writer will know what those things are), Lieutenants were people trained for the mission to get me stupidly killed. Cannabis helped get me through my tour, but I hear they drug tested during his active service days, as they probably do now. By the way, before I went to the Land of the Little People, I washed out of OCS because I couldn’t look like an officer should.

But then I was in a different army in a different time.

Report comment

This article brought tears to my eyes. I saw the new Joker movie last night and I woke up feeling really uncomfortable in my own relationship to crazy. There are so many messages in our society about fearing madness, and the biological origins of madness, and yet we all have it in us and we ALL long for the kind of camaraderie that people get in the military. Last night as I was watching the film I kept thinking about the irony that so many people are living vicariously through the violence in those kind of films and then locking up and drugging the people who are unlucky enough to get the diagnoses. I’m grateful to see this article and I’m glad it’s out here to expand the conversation about healing from trauma, individually and collectively. Good work.

Report comment

I notice lots of people who work in Mainstream Mental Health for some reason seem to live not too far away from “the Joker” they mightn’t act out, but its very much in there.

Report comment

“I saw the new Joker movie last night and I woke up feeling really uncomfortable in my own relationship to crazy.”

Mentalism, ableism, classism and ignorance can do that.

Conflating altered states of consciousness, a trauma history, not taking psychiatric drugs, being poor/disenfranchised, or a passion for social justice with “incurable” brokenness, violence and extremism can do that. Talk about fear mongering and victim blaming.

Exploiting mentalism, ableism and classism to make a film seem “ground breaking” and “deep” is “the joke”. Only it’s not funny.

Full disclosure I haven’t seen this film but I looked up the plot and wow. It would be quite the task not to internalize the underlying bigoted, disempowering, and harmful messages. I’d rather not spend time having to tease all that out and reject it. I work hard at perfecting my BS filter, but still. I could donate the money I would have spent on that film to an organization advocating for social change instead. Thank you for the warning and sorry to hear that happened to you.

Report comment

Great article Drew! This is the direction we need to take mental health in this country, and I’m happy to see programs like DE-CRUIT being featured. Also, very happy to hear Craig Manbauman’s story, and what sounds like him creating an SVA chapter at Long Island University Brooklyn!

Report comment

The concept of “Healing” is just a further way of abusing survivors, getting them to live without public honor and to see that as morally superior.

Report comment

Drew and MIA, I am thrilled that you have featured the phenomenally wonderful DE-CRUIT program here! In DE-CRUIT, the brilliant Stephan Wolfert has conceived, created, and implemented with so much art and heart a way of helping veterans without pathologizing them, without using risky approaches like psych drugs or forced “treatment,” and with a way of using theatre and other literature to reconnect with aspects of themselves, with the arts, and with the humanity of themselves and others, as well as — importantly — with Stephan and with their DE-CRUIT classmates. The work that Stephan and Dr. Alisha Ali have done in documenting the powerful effectiveness of DE-CRUIT and _why_ it works is also tremendously important.

I had the privilege of attending an event at which DE-CRUIT participants performed Shakespearean monologues and poetry they had written themselves, and what was stunning was that, both those veterans who are or want to be actors and those who are/do not, the depth into which they dove in exploring or creating the material and presenting it and the honesty and integrity with which they did it were all too rare onstage and in life. This is a tribute both to Stephan and to the veterans. The night I attended that event, I said I wished that every veteran could have the chance to participate in DE-CRUIT and urged that they — and Eric Tucker’s BEDLAM Theatre Co. in which DE-CRUIT was born — create a video to help spread the word.

I have two other comments. One is that I hope that the nonpathologizing, even DE-pathologizing nature of DE-CRUIT comes through strongly enough in Drew’s article that the use a number of times of the dangerously pathologizing term “PTSD” is understood by readers to mean “people who have been traumatized by military experiences and/or by homecoming experiences and have wrongly been given the pathologizing ‘PTSD’ label when instead their reactions are deeply human ones that should never be pathologized.” Although many MIA readers would automatically make that translation in their heads each time they see a term for a psychiatric “disorder,” for some, there is the danger that any mention of one of these labels without a reminder that such labels are unscientific and expose the labeled person to a wide array of kinds of harm runs the risk of perpetuating the harm of such diagnoses.

My other comment is based on my experience when I blogged for Psychology Today. There, I wrote about a great variety of such subjects. I found that any time I wrote about veterans, the number of readers ranged from 30% to under 3% of the number who read about any other topic. As I wrote in my book, https://www.amazon.com/When-Johnny-Jane-Come-Marching/dp/150403676X/ref=as_li_ss_il?crid=1QTVHBGHEWJI&keywords=when+johnny+and+jane+come+marching+home&qid=1554480516&s=gateway&sprefix=When+johnny+and,aps,220&sr=8-1-fkmrnull&linkCode=li1&tag=whejohandja0d-20&linkId=1dbd7dedc192a717801d8a2ccc9ed082&language=en_US, nonveterans — who represent 93% of the U.S. population — don’t like even to _think_ about veterans, as those percentages show. As an experiment, after I saw those figures, the next time I wrote an essay about veterans for Psychology Today, I made sure the headline did not reveal that veterans were the subject. Within about three days, that essay received as many hits as my other articles that were not about veterans. I see a similar pattern here. I think it is wonderful that MIA plans to publish articles about veterans and trust that they will be about depathologizing them, but it is poignant that so few comments have been posted in response to Drew’s article, and I hope that that is not a reflection of low readership. Nonveterans who have been pathologized and otherwise harmed in the traditional system would do well to make common cause with veterans, because the system has done them harm in so many of the same ways to people in both groups, and people who have not been labeled and “treated” are often frightened by appalling stereotypes of both “mental patients” in general and of veterans as Other and as dangerous.

Report comment

As COO of DeCruit, I need to respond to Ms. Caplan incorrectly stating that DeCruit was born out of a theater company in NYC. As any preliminary research will show you, including reading Mr. Wiggins article, Mr. Wolfert has been doing this work for over two decades. DeCruit is a natural progression of his work with VCPA (Veteran’s Center for the Performing Arts) and Shakespeare and Veterans in partnership with Alisha Ali, PhD NYU Steinhardt. Mr. Wiggins, thank you for covering the stories of the veterans that fight for care that serves them. For more information please go to http://www.decruit.org

https://www.amazon.com/Weve-Been-Too-Patient-Radical-dp-1623173612/dp/1623173612/ref=mt_paperback?_encoding=UTF8&me=&qid=1563414571

https://www.psychotherapynetworker.org/magazine/article/2340/point-of-view

Report comment

Dawn, is that you replying as “ArmyWife”? I appreciate the clarification. If someone can tell me how to correct that mistaken phrase in my comment, I am happy to do so! I did of course read the article but did not see a mention of VCPA (Veteran’s Center for the Performing Arts). I know Stephan has done work combining Shakespeare and his own military experiences in his brilliant, one-man show, CRY HAVOC! which I have seen praised to the skies and urged everyone I know to go see. When I learned about DE-CRUIT and saw the performances of some of the veteran/students participating in Stephan’s Shakespeare class, it was the night that it was done in conjunction with Bedlam Theatre, and Stephan and Bedlam’s founder Eric Tucker (also a veteran, who I believe directed CRY HAVOC! at least at some point) and I talked that night about disseminating the work and the principles of it as widely as possible. It now strikes me that Bedlam is not mentioned anywhere in the MIA article, so are DE-CRUIT and Bedlam no longer connected? I am very much aware of and a great admirer of Alisha Ali’s work in general and with DE-CRUIT, and she and I are longtime colleagues and friends. In fact, after Stephan came with Alisha to the NYC premiere of my film about the tragic and unhealthy divide between veterans and nonveterans, “Is Anybody Listening?”, isanybodylisteningmovie.org, I was delighted to meet Stephan, and Alisha and a number of my other friends and colleagues talked at length afterward, which was when I began to learn about her work with Stephan on DE-CRUIT. I continue to wish that there could be this glorious use of theatre for veterans — and indeed for other traumatized or otherwise suffering people — everywhere! And Dawn, if you are the one who wrote that above comment, I had the pleasure of meeting you at an LA performance of CRY HAVOC! and know how crucial a part of the work you are.

Report comment