Peace, joy, healing. You can see it, plain and powerful, in the faces of those who make music on the path to recovery. You can hear it as they speak of music’s role in their journeys out of psychiatric darkness and into the light of reclaimed lives.

Just watch and listen to those who harmonize through Sing Your Heart Out, an English program that’s open to anyone with any story — some with psychiatric diagnoses, some without, no questions asked either way. Or hear the words of James O’Flynn and his band, the Claddagh Rogues — among the many who gather for music and fellowship at 49 North Street, a well-being initiative in Skibbereen, Ireland.

Some say that music literally saved their lives, pulling them from the brink of suicide. Others say its mental-health benefits have played a significant role in their quest for wellness, providing relief from depression, anxiety, addiction, and freedom from hospitalization, incarceration, homelessness. “It kept me together,” said O’Flynn of the songs he created to carry him through his time in institutions. “It was the only sanity I could find.”

This all begs the question: Why? What is it about music that makes it such a potent and transformative force for healing? As a species, we like it — that’s obvious enough. But what does the science say about it? What can it tell us about music’s impact on our cognition and on our mood, on our capacity for empathy, and our sense of connection with others? How does it change the brain, an organ exquisitely designed to respond to its environment? In the process, how does it change us? In study after study after study, the links between music and wellness have been repeatedly confirmed, as scientists keep digging into its social, emotional, mental, and neurological effects.

“Music is good for us,” said Steven Mithen, an archeologist with the University of Reading, UK, and author of the 2005 book The Singing Neanderthals: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind and Body. “It’s been known for many, many years that music has therapeutic properties. It’s been in all sorts of areas — people who’ve got mental stress or physical pain. Doctors use it during operations, during dental surgery. . . . But nobody’s ever explained why it does have these therapeutic properties. Why is music so good for our well-being?”

“The medicine of the soul”

None of this is new — not the questions sparking inquiry from researchers, not the widely held conviction that music benefits us. A belief in its significance, even a mystical faith in its restorative properties, has gripped the minds of poets and philosophers since the dawn of both. The ancient Egyptians used musical incantations to heal the sick; the Ancient Greeks played flutes to calm the agitated and dulcimers to aid the sad. Plato, one of Greece’s greatest sages and one of music’s biggest fans, declared it “the medicine of the soul.”

“Music produces a kind of pleasure which human nature cannot do without,” opined Confucius, and a couple of thousand years later, Talking Heads frontman David Byrne argued more or less the same. “You can’t touch music — it exists only at the moment it is being apprehended — and yet it can profoundly alter how we view the world and our place in it,” he writes in How Music Works. “Music can get us through difficult patches in our lives by changing not only how we feel about ourselves, but also how we feel about everything outside ourselves. It’s powerful stuff.”

Kahlil Gibran once called it “the language of the spirit. . . . bringing peace, abolishing strife.” Or, in the words of Louis Armstrong: “Music is life itself.”

No single piece of research has verified such wisdom with raw data. But taken together, analyses exploring the neurology, psychosocial impact, and evolutionary underpinnings of music suggest that all those gurus were onto something. A vast range of studies examining functional outcomes illuminate its impact on how we think, how we learn, how we feel, how we age, and how we recover from illness and damage to the brain.

Cognitively, music assists in developing and maintaining “executive function” skills, helping kids and adults alike tune out distractions and nimbly navigate tasks. Children see improvements in math and language; kindergartners taking piano lessons are better at recognizing words. High schoolers who continue with music get better grades. Adults who play music have more plastic and adaptable brains. Stroke victims who listen to music recover faster. Parkinson’s patients who dance to music see improvements in their mobility, with tango helping them most of all. Music helps improve symptoms of depression. It helps memory, depression, and anxiety in people with Alzheimer’s.

Group music-making nurtures social skills in people of all ages. Teenagers in extended music classes enjoy enhanced social lives. Four-year-olds display “cooperative and helpful behavior.” Even babies respond to music: In one 2014 study, 14-month-old infants who bounced to music in synchrony with researchers later helped them pick up objects dropped to the floor. The authors conclude: “Interpersonal motor synchrony might be one key component of musical engagement that encourages social bonds among group members, and suggest that this motor synchrony to music may promote the very early development of altruistic behavior.”

All such research, so far, points to clear ties between music and wellness, and it confirms the impression it leaves on the brain. (For a clever summary of more 200 studies on the myriad benefits of music, see this roundup on starsandcatz.com.) But the neurological dimensions of that impression — and, again, the whys behind them — include many unknowns. Illuminating and analyzing music’s benefits requires a gradual and meticulous analysis of exactly how it affects us, and precisely what goes on.

“The science is slow,” wrote neuroscientist Thibault Chabin, responding via email to questions on a recent French study that tracked the pleasure response of musical chills with EEGs, “and we need to understand mechanisms brick by brick.”

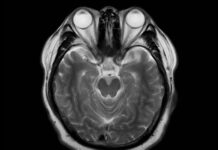

Also: the brain is really, really complicated. As Daniel J. Levitin points out in This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession, “It is difficult to appreciate the complexity of the brain because the numbers are so huge. The average brain consists of 100 billion neurons.”

Any one of us has more thoughts or brain states than all the known particles in the universe, he says. And as Byrne pointed out, music doesn’t even exist unless we’re there to process it. Any given snatch of it is assembled in silence, traveling on soundwaves that ripple through the air — set off by the snap of vocal cords, or the pluck of a guitar — until they smack up against an eardrum. Those sound waves cause vibrations that move from middle ear to inner ear and the cochlea. There, tens of thousands of hair cells shimmy, causing electrical signals that neurons ferry along to the cerebral cortex — which then begins the hugely complex, profoundly human business of turning them into music.

A full-body workout for the brain

But music isn’t just one thing — and it takes myriad provinces of the brain to take all of its elements, decrypt and then assemble them into Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” or a song belted out in the shower. Rhythm gets uncoded on the right side, in the auditory belt and parabelt. Melody and harmony are channeled mostly in the auditory cortex of the temporal lobe, with assists from other areas; anticipation, a key piece in the enjoyment of music, builds in the prefrontal cortex. Other regions get involved, too: the hippocampus (memory), the visual cortex (reading music), the motor cortex and sensory cortex (making music or dancing), plus all the many zones of neurological real estate involved in emotion.

“I don’t think that there is anything besides music,” said Sarah Lock, executive director of the Global Council on Brain Health (GCBH) and senior vice president for policy at AARP, “that engages so many multiple parts of the brain and helps them work together.”

The result is the gray-matter equivalent of a full-body workout, building flexibility and muscle across the brain. As Oliver Sacks writes in Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain: “Anatomists today would be hard put to identify the brain of a visual artist, a writer or a mathematician — but they would recognize the brain of a professional musician without a moment’s hesitation.”

Again, this begs the question: Why? What happens inside our brains when people engage with music? Whether you play it, sing it, hear it at a concert or listen to it on your morning commute, it lifts the mood and lowers anxiety, firing off endorphins, releasing dopamine and deregulating cortisol.

Or consider the sensation of “chills,” that tingling pleasure many of us feel when we experience music we love — be it that snippet of Beethoven or a track from Drake. According to Avram Goldstein’s germinal 1980 study, roughly half of us get them while listening to music. For those who do, they’re unmistakable — sneaking up the spine and crawling around the scalp, a tiny blast of sensory fireworks that both anticipate the thrill of a favorite musical phrase and add to its pleasure. Their effects have been documented over the years by researchers looking at music’s effects on reward circuits in the brain (and the implications for people with depression) as well as the neurotransmitters and other “biochemical messengers” that respond.

In Cortical Patterns of Pleasurable Musical Chills, published in November in Frontiers in Neuroscience, Thibault Chabin and his colleagues at the Université de Bourgogne Franche-Comté in Besançon captured and tracked musical chills via electroencephalography (EEG), an approach that opens new directions in studying the neurology of musical pleasure. Electrodes attached to the scalps of 18 participants showed activity in the orbitofrontal cortex, an area of the brain — located just above the eyes — that’s closely associated with emotion and memory.

While the scalp results did not directly involve the brain’s reward structures, the activity did align with past research using fMRI and PET, Chabin said. Both of those are heavier, more unwieldy neuroimaging machines that can only be used in laboratories. EEGs, by contrast, can be taken into the field and used to track such electrical activity in people experiencing music in groups.

That’s the main significance of the recent study, Chabin said — to demonstrate that “musical pleasures and the chills” can indeed be captured with electroencephalography for future experiments. “The question of ‘why’ is essential,” he wrote, “because we know how it can be pleasurable, so future researchers should prove why. The fact that it recruits reward circuits involved in motivated behaviour, essential on the survival plan, such as sex, food, money etc., is intriguing.”

The mechanisms of musical pleasure

All of those pleasure sources have clear benefits for individual humans and the species — among them, staying alive and thriving. But as past studies have suggested, different clusters of reward circuits in the brain are engaged with different types of pleasure. Or not engaged, as exhibited in different types of anhedonia, i.e., an inability to feel pleasure. Failure to take pleasure from money is one type, leaving one part of the brain disengaged; failure to take pleasure from music leaves another part disengaged. This means that people can take high pleasure from music and not from money, or high pleasure from money and not from music.

With the EEG scans, Chabin said, three brain areas are “supposed to reflect” the mechanisms of musical pleasure. One is the prefrontal area, which is involved in emotional processing. Another is the temporal area, involved in auditory processing and linked with the orbitofrontal cortex; he cited recent research, published last year by Alberto Ara, that identified it as key to musical appreciation. Also involved, though less significantly, is the central area, which “we linked with the supplementary motor area involved in motor planning and maybe involved in rhythmic planning” as well as “musical imagery” — that is, the ability to conjure a tune in your own head.

As Chabin emphasized, the latest EEG research follows numerous other studies on the topic over the years — starting with Goldstein’s, which confirmed opioid peptides, i.e., endorphins, as part of the chemistry of chills by successfully blocking them with the opioid “antagonist” naloxone. The neurochemistry and emotional rewards sparked by music, and the self-reported experiences of those who feel them, have been re-confirmed in the four decades since.

In a 1991 study exploring physical responses to music, more than 80 percent of respondents reported “shivers down the spine, laughter, tears and lump in the throat.” In a 2009 study examining the link between subjective and objective effects of music, researchers showed that, yes, the intensely pleasurable chills felt by people listening to their favorite music equate with arousals in the sympathetic nervous system. Ten years after that, another study showed the neurotransmitter dopamine, the so-called “happy hormone,” plays a causal role in musical pleasure. A study from last year confirmed dopamine’s role in “mediating” same.

In another, as-yet-unpublished experiment, Chabin and his colleagues simultaneously scanned the brains of 15 people during a concert, tracking their physiological parameters — heart rate and skin activity — while they reported “their subjective emotional pleasure,” he said.

“The aim was to study how people share similar emotional experiences when they live a situation together, how they influence each other, if their neurophysiological activities are coupled in some part of the concert and try to understand how and why.” At this point the results are confidential, but he called them “exciting.”

Why is all of this important? In Chabin’s view, because music itself is important in the lives of so many people — “like no other hedonic stimulation.” To understand the cerebral processing behind such pleasure could mean using music “to treat, or at least to soften, effects of several diseases.”

Music on our minds, and on our bodies

While hard science trains a lens on the brain, other research weighs the self-reported experiences of people themselves — and overwhelmingly, they say that music makes them feel better. Such are the findings of the GCBH, an international brain-health consortium that examined the impact of music on adults of all ages, training a particular eye on older populations. Formed by AARP in 2015, the council held a conference in February of 2020 that explored the role of music in improving mental health and well-being.

Its conclusions were unambiguous. “Any type of musical engagement – including singing, dancing, playing an instrument, composing music, and listening to music – appears to hold benefits for adults age 18 and older.” Further: “A higher percentage of adults who engage in music self-rate aspects of their cognitive function, brain health, quality of life, and happiness as excellent or very good. Adults who engage in music also report lower average levels of anxiety and depression.”

The full report, “Music on Our Minds: The Rich Potential of Music to Promote Brain Health and Mental Well-Being,” is based on the conference and accompanying survey of 3,185 respondents aged 18 and over. Conducted online, the survey showed small but significant ties between music and wellness.

“Adults who engage in music are more likely to self-report their overall health, brain health, and cognitive function as excellent or very good,” it states in its list of key findings. “Listening to music shows a small, positive effect on mental well-being, depression, and anxiety. This includes listening to music in the background, attending musical performances, and focused listening to recorded music.”

According to the survey, those who listen to music at least half the time they engage in “everyday activities” report slightly higher mental well-being and slightly lower depression and anxiety; they also remember names better, learn new things a little more easily, finish what they start more regularly, and claim better brain health overall. More focused listening to recorded music and live attendance of musical performances also yield positive effects on self-reported well-being, anxiety, depression, and brain health.

The survey “showed us that even listening seems to be beneficial — and that’s another great thing about music,” Lock said. “It’s not just for those gifted people, right? It’s for everyone.” And for the older population, she added, “It really is a boon to healthy aging.”

When it comes to more active engagement, the survey shows that adults of any age who have ever — ever — participated in musical activities report better memory, capacity to learn, quality of life, overall health, and brain health. In the subset of adults over 50 who’ve actively engaged in music, they self-rate their cognitive function, happiness, and quality of life higher than those who haven’t. The larger report also cites research showing the benefits of active engagement over listening alone, and it notes the role of improved neuroplasticity — which aids memory, reason, adaptability, and focus, and creates a “cognitive reserve” that can help a brain rebound following injury or disease.

“Not all cognitive reserves are created equal,” it states. “People who have exercised and challenged their brains throughout their lives gain an edge. And it turns out that musical training is an effective way to help build the valuable cognitive reserve.” Taken together, the visual, auditory, and physical aspects of music-making all add up to a cognitive boost. “Studies suggest that people who engage in music-making as they age, either as a profession or a hobby, appear to have better brain health over the course of their lives compared to non-musicians.”

Childhood exposure is a big assist. But as the AARP report emphasizes, it’s never too late to start: For those 65 and older, current engagement in music “amplifies the mental well-being effects of early music exposure or ‘makes up for’ a lack of initial musical exposure. Adults with no early exposure to music but who currently engage in some music appreciation show above-average mental well-being scores … thus ‘making up for’ this lack of early exposure.”

In addition, the report stressed the social bonds encouraged by music, helpful in an age when omnipresent smartphones can lead to isolation. It builds social connections. Simply listening to music encourages empathy, as exhibited in brain scans of college students.

Overall, Lock said, the findings of the survey and the round-up of research in the report all point to music as a powerful, widely accessible, and relatively inexpensive force in shaping wellness over lifetimes. With the Global Council’s input from international participants, she noted public-health movements in Asia, Canada, and elsewhere to open up avenues for music as therapy — making it easier for people to practice it and more accessible to people in need.

“Here in the States, we have a lot to learn,” she said. Such approaches could help many and might well be implemented “without having to spend tons of money on the concept.”

No, Lock said, music is not a cure-all. “You don’t want to oversell what it can do. It can’t cure dementia. But it can make life a heck of a lot better.” And as a tool for well-being, she said, “It’s incredibly cheap, it speaks to many people, and it’s shockingly powerful.”

Prescribing music for what ails us

Given that trifecta of compelling characteristics, why not prescribe it as an alternative form of treatment? Debra Shipman makes precisely that point in “A Prescription for Music Lessons,” her 2016 paper in the Federal Practitioner.

“Playing an instrument may help decrease the need for antidepressants and provide a healthy recreational activity,” she writes. “Based on its physical and mental benefits, learning to play a musical instrument should be explored as complementary alternative medicine. Compared with filling prescription medications over an individual’s life-time, the cost of a portable keyboard is substantially less.”

Making her argument, she lays out the research showing all the reasons why anyone — old or young, healthy or facing a physical or emotional challenge — should take up an instrument.

It alleviates stress: one study shows that playing the piano can lower cortisol. It helps depression and post-traumatic stress disorder: in a study of the Guitars for Veterans program, symptoms of both were alleviated after only six weeks of lessons. It can help lower the risks for dementia: another study, weighing the benefits of various leisure activities, determined that people who play an instrument are less likely to experience dementia than those who spend their time with crossword puzzles or reading.

Among the many articles cited is a clinical treatment report, published in 2012, that tells of a 91-year-old patient who, suffering symptoms of depression and psychosis, sat herself at a piano and played. Afterward, her vocabulary improved. Her mood improved. Her insight and ability to talk about her health improved. And while the woman never played again, Shipman notes, “the improvement in mood and cognition were sustained for several months.”

Throughout her review, she quotes a wide colloquy of voices affirming the effects of playing music. But she has a personal take on the subject as well. After completing her Ph.D., she explains in the article, she started piano lessons as a hobby — and its pursuit helped her navigate her father’s Parkinson’s disease. His own lessons on the instrument helped him navigate it, too.

Studying the piano “helped him to mentally deal with his disease. Dad genuinely looked forward to his music lessons and was able to focus on practicing the piano rather than on his disease,” writes Shipman, a nurse educator with Veterans Affairs in Salem, Virginia. “I believe playing the piano prevented him from becoming depressed and kept him engaged.”

James Folger was a boy when a drunk driver struck him on his bicycle, causing a traumatic brain injury that eventually led to his disease. But when his daughter first told him she planned to study piano, his response was immediate: I’m gonna take piano lessons, too. “And I thought, ‘How great is that?’”

He took lessons for several years — until the Parkinson’s progressed too far, and he physically couldn’t play. Folger never made it out of the first book on music technique, Shipman said, but that didn’t matter. What mattered was the chance to train his attention on something new.

“He would say, ‘Oh, I’m gonna go do my homework today’ — and it would give him a different focus.” The effects of that focus were clear: “It made him feel good. It made him feel like he was accomplishing something. It made him feel like he was doing something positive for himself, because he couldn’t hike, he couldn’t fish. And I believe it helped with his finger dexterity.” Beyond that, “He was in a better mood when he played the piano. . . He felt he was contributing, and he was doing something for himself. And I could see a difference when I was over there and he would play.”

Her father died in January of 2017. A little over a year later, Shipman said, her mother Carolyn “died of a broken heart.” In the two years since, playing the piano has helped her navigate her grief — seizing the mind and keeping it in the moment, one of music’s most healing gifts. It provides an escape.

The list of other therapeutic benefits goes on: the sense of achievement, of setting a goal and attaining it; the lowering of barriers, the building of community, the “connectivity” uniting people from different backgrounds and generations; and with it, the relief from solitude and pangs of despair. In one 2001 study cited in Shipman’s paper, older participants who took music classes felt less lonely, less anxious, and less depressed. People who cope with such struggles, she wonders: Why not get them a keyboard? Why can’t music be the prescription that sparks them toward well-being, moving them forward?

“You could be in a wheelchair, and you could still play piano. You could be without legs, and you could still play piano or violin.” The joys of music are out there, ready to be tapped. “I think,” she said, “it helps people cope.”

What’s the dosage?

Music isn’t the only creative undertaking that offers therapeutic benefits — research shows the arts in general are healing, too. But if a daily dose were prescribed, how much would we need?

About a quarter of an hour.

According to a 2011-2012 survey from Western Australia, that’s the minimum amount of arts engagement that can help nudge anyone toward improved well-being. In a representative survey of 708 telephone respondents, people who participated in the arts for 100 hours or more per year reported well-being around two points higher (on the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale) than those with less.

Give or take, “That translates to two hours a week, and that translates to 15 minutes a day,” said Christina Davies, a researcher with the School of Allied Health at the University of Western Australia and author of the study. It’s listening to a few favorite songs on your way to work each day. It’s going to a concert with friends each week. She added: “It’s quite easy to do.”

Published in BMC Public Health in 2015, The art of being mentally healthy aimed to quantify — and at the same time, demystify — the relationship between the arts and wellness in the hopes of establishing guidelines moving forward. “This is the first study to quantify the dose-response relationship between recreational arts engagement and mental health in a general population,” it states, “and is a starting point as to whether a population-based arts engagement strategy can be utilised to improve the mental well-being of the general population.”

A causal relationship between the two would mean “potential for new and innovative ‘time based’ arts-mental health campaigns.”

In a video call, Davies said the gist of any health directive needs to be simple, straightforward, and gettable, as in: “The arts are good for mental well-being.” And it needs a number attached to it: If the arts are good for us, how much do we need? That’s the “dose-response,” and it’s key to helping people understand just how much of a certain activity is beneficial for health.

In Western Australia, a public-health campaign urged adults to “Find Thirty” minutes a day of physical activity. Similarly, the 15-minute threshold for arts engagement frames healthy behavior in attainable, everyday terms. And once that message gets out, she said, “It seems doable.”

Finding, and prioritizing, the links between arts and health are an ongoing and central facet of Davies’ work, which also includes a 2014 qualitative study breaking down self-reported outcomes of arts engagement and a 2016 paper explaining arts-and-well-being concepts and terminology for health professionals. The latter lays out the lexicon in easy-to-grasp ways. What is arts engagement? Performing arts, visual arts, digital arts, festivals and fairs, literature. Is art therapy and arts engagement the same thing? In short, no. One is a form of psychotherapy; the other is a source of everyday enjoyment for the general population.

Confusion on that point is one of several assumptions complicating people’s attitudes toward the arts. Another is the notion that creative undertakings are a luxury, or should be — causing many to feel guilty about time and money spent on them. What’s more, many folks don’t even realize that what they’re doing is arts engagement. If they’re listening to music, that’s art. If they’re sitting with a coloring book on their lunch hour, that’s art.

Davies uses the sports analogy: Some folks like hockey, some folks like football, some folks like tennis. As with sports, the arts are a widely enjoyed activity with clear health benefits. And, as with sports, you needn’t be a high-achieving professional to reap them.

“People think they need to be good at art to do it. That’s not true,” she said. No one tells a three-year-old to stop making pictures because her art is sub-par. And yet, she said, “I think, as we get older, we have this need to be Picasso, or we don’t do it.”

The key is doing what you enjoy. For Davies, it’s painting: Hanging in the background on her video call was a vibrant artwork of her own creation, its kinetic blue spiral exploding cheerfully behind her.

“I think we need to change the way that the arts are valued. I think very much, the arts have been promoted as ‘arts for arts’ sake,’ and I think that’s wrong. I don’t think we can do that anymore.” The arts are too valuable, she said — and too often at risk of defunding. Emphasizing their impact and importance for well-being would help assure their health, and ours. “It’s very hard to cut funding for the arts once we recognize things like impact.”

And it’s not as though any of this is new, she added. Look at the role that music and the arts have played in healing over the course of history. Look at Florence Nightingale, the mother of modern nursing, who observed and promoted the soothing effects of music on patients in her care. Look at those ancient Egyptians, at those ancient Greeks, at the even more ancient rituals and relics going back thousands upon thousands of years.

“We’ve been doing it,” she said. “So why have we suddenly forgotten?” Maybe now is a good time to remember, she said. And to ask: “Can we promote, maintain, and improve mental well-being or recovery if we now focus on the arts, or especially music?”

Lessons from prehistory, and Hmmmmm

Yet again, the whys loom — not just why we’ve forgotten, but why music mattered so much from the start. This question, the biggest why of all, is the evolutionary, existential whopper behind all that music means to us as human beings. Our own experience tells us music makes us feel good; science breaks down the mechanisms; surveys tally how much and how widely we feel it. All of that suggests that music is fundamental to our natures.

If music is indeed innate and hard-wired within us, neuroscientist Chabin wants to know the underpinning reasons. The involvement of dopaminergic circuits suggests something deeply rooted in our past, and several hypotheses have already been floated: Maybe it was key in sexual selection, maybe social bonding, maybe a question of interpersonal emotional communication. That’s their next step in research, he said, and scientists are far from resolving the question. That 35,000-year-old bone flute uncovered from the Ice Age, for instance: What purpose did it serve?

“It is precisely what we want to know by studying all of this,” he said. “What is the ancestral function of music?”

Steven Mithen, the archeologist based in England, has an answer: Hmmmmm.

That’s his term, outlined in The Singing Neanderthals, for the “proto-musical language” that, he theorizes, fully emerged around 350,000 years ago after millions more of gradual evolution. Six million years ago, apes’ and humans’ shared ancestors started vocalizing. Two million years ago, as they stood upright and their tooth size shrank, their vocalizations also evolved. Half a million years ago, their brain size grew.

By the time Neanderthals appeared 150,00 years later, those vocalizations had developed into Hmmmmm — an acronym unpacking all the various aspects of quasi-musical communication that would have made it useful for our early ancestors. It was holistic, relying on larger phrases versus words; it was manipulative, useful in persuading people; it was multi-modal, employing both body and voice; it was musical, varying pitch, timbre, and rhythm to various ends, whether expressing emotion, bonding with a group, soothing infants, or luring mates; and it was mimetic, involving imitation of sounds from the natural world.

All of this boils down to one core argument: Singing was easier, anatomically, than verbal communication, allowing early humans to create families and nurture ties between them. It promoted connection. It created a sense of togetherness. And it came first. As a result, Mithen argues, music takes us back to our most essential, natural state; in so doing, it calms and connects us, giving us a sense of self and belonging to a group. Unlike spoken language, which can cause stress, music alleviates it. It brings us back to our time in the cradle as homo sapiens.

“Our early human ancestors communicated in a form of language that was basically musical in nature,” he said in a phone interview, “because, at that time, they didn’t have words. They didn’t have vocabulary. They didn’t have grammar. So the way they expressed emotions, the way they passed on information, the way they built social bonds between each other and built trust was very much through singing and dancing together. And that has remained as part of our nature of being.”

And its long-recognized healing properties? “Music is so good at developing your own self-expression, and also building friends and building all that sense of being a member of a group — and also learning to cooperate with people. So, so many benefits,” he said, “and they’re all rooted in our evolutionary past.”

In a new paper for the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences, Mithen and other researchers lay out the cross-disciplinary arguments for Music as a co-evolved system for social bonding — meaning, a system in which human genes and culture evolved together. As proto-music emerged, it fed culture; as the culture of music emerged, it fed social bonds; as those social bonds emerged, they fed back to our genes. Their arguments span everything from archaeology to neuroscience and analyze “deep links” between social reward and elements of music, drawing out the physiological and behavioral evidence across cultures.

“Music’s universal power to bring people together across barriers of language, age, gender, and culture sheds light on its biological and cultural origins,” it concludes, “and provides humanity with a set of tools to create a more harmonious future – both literally and figuratively.”

The conversation — at times a debate, at other times a dispute — among anthropologists, ethnomusicologists, and archeologists regarding music and its likely evolutionary underpinnings is longstanding and ongoing. As Mithen observes, all the way back in 1871, even Charles Darwin heard singing among our hominid forebears: “It is probable that the progenitors of man, either the males or females or both sexes, before acquiring the power of expressing mutual love in articulate language, endeavoured to charm each other with musical notes and rhythm.”

But in the century and a half since, scholars have grappled with music, debating not its ubiquity and significance in human experience but its necessity in evolutionary terms. Is it something that evolved from some Darwinian imperative — making babies, bonding tribes, aiding communication on the hunt?

Or is it, in the words of linguist and psychologist Steven Pinker, no more than “the making of plinking noises” and “auditory cheesecake” — that is, a tasty and pleasant byproduct that doesn’t really matter and never really did, at least in evolutionary terms? He saw it not as adaptation but technology. And from a biological perspective, he said, it was “useless.”

This infamous brush-off of music needled many academics, Mithen among them, who have come to its defense in the decades since with arguments exploring present and past scholarship — and the powerful links between music and emotion. He articulates his case in The Singing Neanderthals: “We don’t have emotions for free or for fun: they are critical to human thought and behaviour, and have a long evolutionary history. . . . Emotions are deeply entwined with the functioning of human cognition and physiology; they are a control system for body and mind. It is most unlikely, therefore, that our deepest emotions would be so easily and profoundly stirred by music if it were no more than a recent human invention. And neither would our bodies.”

We snap our fingers, tap our toes. Even when we’re sitting still, he writes, “the motor areas of our brain are activated by music.”

Connecting with our ancestors and ourselves

On the call from England, Mithen did not claim that music plays quite the same role as it did back when homo sapiens first mouthed sounds on the savannah. Now that we have spoken language, we don’t use it as much for the simple reason we don’t need it as much. That’s inevitable.

But the capacity is still there, waiting to be tapped — even for the unschooled and the pitch-deficient. In the course of Mithen’s research, he took a year of singing lessons and tracked the changes via brain scan. “I was awful at singing,” he said, adding that his wife, a choir member, has instructed him never to sing in public. Nevertheless, the results showed increased activity in some areas, decreased in others — the sum of them pointing to an innate musicality installed via evolution over millions of years.

As a result, music returns us “to an early state of being that we feel comfortable in — and it has that consequence of giving us a sense of personhood, giving us a sense of being part of a community,” he said. It’s almost in our collective memory, “in our DNA of things that are good for us,” simply because we spent so much time as hunter-gatherers communicating in music, minus words.

Mithen doesn’t argue that words aren’t handy. We wouldn’t be here, living in a 21st century with all of its technological advances, were it not for the complexity and scope of verbal language.

“We couldn’t have invented agriculture, or cities, or had an industrial revolution without language,” he said. “But that all causes us some degree of mental stress, unhappiness, and so forth. And music takes us back to a time when that was the primary nature of being human — and we can still recover that in ourselves. And it gives us a sense of well-being, and calmness, and engagement.”

Happiness is important

If music restores us to our human essence, the implications are clear. The lessons of prehistory hold relevance today, or should, for mental-health policymakers and others who fund and shape priorities at all levels of society. For one, said Mithen and others, music shouldn’t be cut from schools. For another, its therapeutic powers need to be utilized more widely — especially now. COVID-19 has brought the importance of wellness to the forefront, emphasizing both the rising incidence of loneliness, depression, and anxiety and the pressing need to find new ways to address them.

“We really need to find a way to sing in the current pandemic to bring people together,” Mithen said, and he was not alone in voicing such concerns. Davies, the arts-and-health researcher out of Western Australia, reflected on a phrase that kept appearing in the comments on her arts survey: It makes me happy. “The word is ‘happy.’ So this is very, very much about mental well-being,” she said. “And happiness. Happiness is important, especially during a pandemic.”

Indeed, research confirms in the hardest numbers that people are hurting. The impact on psychological distress has been documented worldwide, with results from two studies — one in the U.S, one in China — showing around 53 percent of respondents citing the pandemic’s ill effects on their mental health.

But research also confirms that even amid the ongoing health crisis, music helps. Chabin pointed to a recent study, Rock ‘n’ Roll but not Sex or Drugs, showing a negative correlation between music and depression among more than 1,000 individuals surveyed in Italy, Spain, and the States during the COVID spring of 2020.

“The higher the engagement in music-related activities,” it states, “the lower the depressive symptoms reported by participants in our sample.” (For the record: Food helps, too.) The paper refers to all the piles of earlier research affirming music’s ability to alleviate depression, regulate mood, promote well-being, and rev up the underlying reward mechanisms in the brain, which the new results also suggest. Overall, the authors say, “Our data have practical significance in pointing to effective strategies to cope with mental health issues.”

And so, once more, the research points to the beneficial properties of music. The science all says so: Music heals. It benefits the brain, the body, the spirit, and the social bonds that glue us together. It boosts our feelings and soothes our ills. Given the evidence in support, could Steven Pinker still be right? Could music be just some yummy but pointless scrap left on our plates, lacking any nutritive value?

“Obviously, I have a different opinion, but science is a confrontation of ideas, hypotheses, and proofs,” Chabin said. “One more time, we must prove it.”

Cheesecake or not, music is still out there, aiding and cheering many. It’s still forming the basis for forward-thinking recovery programs that prioritize wellness and provide a lift for the depressed, the down and out, the emotionally vulnerable, the chronically ill. It’s still giving people a chance to connect with others, to form new bonds, to find new hope through song or the beat of a drum. It’s still bringing joy to those who gather at 49 North Street in Ireland, at Sing Your Heart Out in England, at other well-being initiatives all over the globe. And it’s still giving a lift to anyone, anywhere, who just needs a blast of music to get them through the day.

Wherever music happens, so can healing.

As GCBH’s Sarah Lock phrased it: “If you could find anything that reduces anxiety, reduces agitation, reduces depression — and is fun and affordable — wouldn’t you use it?”

In the personal segment of Prescription for Music Lessons, Shipman talks about the arc of her father’s health. Even after his Parkinson’s progressed, even as he entered a nursing home, music was still a part of his life. It was still a gift — in the end, her gift to him.

“His mood changes, and he becomes more animated. In his more lucid moments, we play music together. Playing music has a magical way,” she writes, “of creating peace within the mind.” She then turns back to the wisdom of the ancients, quoting that hardcore Athenian music fanatic from millennia yore.

“Music gives a soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination,” Plato asserted. “And life to everything.”

***

Editor’s note: This is the second of a three-part series on music and its impact on well-being. Part one can be found here; and part three here.

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

I have my own way of expressing the value of music in human experience. It actually goes for any activity that involves “mere entertainment value.” This, oddly, includes many many activities currently considered “non essential:” social gatherings, church, concerts, shows, sporting events, movies…

My understanding is based on this quote from our Creed: “…the spirit alone may save or heal the body.”

Spirit, then, is the only true healing agent in life, according to what I have been taught. All other healing modalities ultimately operate through Spirit.

So my way of understanding this is that all these “non-essential activities” including playing, listening to and dancing to music, have healing power because they validate Spirit. Any activity that validates Spirit should have some healing benefit. This would even include the milder forms of education (or study).

Activities that validate Spirit “waste” time and money, provide no nutritional or medicinal value, usually involve no physical product at all, but only temporal experience, and often can be indulged in with minimal technological assistance.

Conversely, activities which invalidate Spirit tend to treat us only as animals or bodies, focus their attention on the brain and chemicals, are seen as “economically essential,” and when put into action tend to enslave and depress.

I believe this understanding, or model, explains all the experimental observations laboriously described above and points the way to improvements in theory and practice in all the healing arts, as well as the other humanities, and ultimately the physical sciences as well.

I appreciate this opportunity to comment on this topic. I really hope that in a few short years we will laugh at the premise of this article (why is music so good for us?) and wonder why we didn’t realize the most obvious answer much sooner.

Report comment

My former Lutheran psychologist should read this article, because she gave me the very bad advise to turn off music. Thankfully, I ignored that bad advice. And what’s bizarre is I can now tell much of my life’s story in the lyrics of music.

I remember the first time I found a song to be seemingly so descriptive of my life. I was hanging out on the roof top deck of my Chicago “brick house.” Some friends and I were listening to “Up on the roof,” and grateful to be there, rather than in the “rat race.”

The second time it happened, I didn’t notice it, until much later. As I was moving out of Chicago, to the suburbs to raise my children. I was driving over the North Avenue bridge, and the “Bridge over Troubled Water” was playing on the radio. And it was in the suburbs that I had the misfortune of running into satanic child molesters, an “evil” child abusing and child abuse covering up Russian pastor, and his satanic child abuse covering up psychologist and psychiatrist friends. Not to mention the “evil” child abuse covering up Muslim psychiatrist and doctor. Children of the corn.

As I was healing from all their anticholinergic toxidrome poisonings, I did some “chasing cars,” and the music lyrics on the radio seemed to coordinate with people’s car vanity plates and the street signs. It was the most staggeringly serendipitous experience of my life, and it seemed like we were all connected.

And when I moved from my healing in the ‘burbs, to healing in Chicago. I was awakened to the concept that the kind and comedic souls of Chicago thought of me as “the tailor who sings with the Lord, who is,” of course, “just and American Girl.” (The Lord and Taylor store in Water Tower Place, my former place of employment, was turned into an American Girl store.)

But, indeed, it does seem like He’s been “Killing me softly with his song, Telling my whole life with his words, Killing me softly with his song,” my whole life. I have a love story in my dreams. And “what’s wrong with that, I need to know….”

Yes, indeed, music helped to save me. And “what doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger,” so I now know to tell my Lutheran psychologists to take a hike, when they attempt to nose themselves into my business.

Report comment

I know this is far-fetched but it’s an idea. Why we like music, why it seems to help us mentally and emotionally, has to do with our association of music with the turning of attention to where it’s coming from and the steady focus of attention on it. This is a very necessary thing for people to focus attention on each one of us so we feel known and safe. When we see people all focusing on music, the association is a moment of safety has taken place, and we were there. If we could make the music, they would focus on us. The more we hear and take in, the more we feel we have the same chance to get people to focus on us and make us safe. The more minds we are in, the more security we have.

Report comment

Thanks Amy for the writing and amount of energy you put into it.

” As Daniel J. Levitin points out in This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession, “It is difficult to appreciate the complexity of the brain because the numbers are so huge. The average brain consists of 100 billion neurons.”

“Any one of us has more thoughts or brain states than all the known particles in the universe,”

I love it when someone points out the landscape of unknowns, although most put themselves above what is known.

I question what would happen to a beautiful piece of music within confines of an office of a doc or the rubber walls of a seclusion, or the straps of force?

Ohh wait, they don’t allow music in there.

Do tell, why not?

Did neuroscience not tell us the effects of music?

Would be a shame to change the words of this song, but it lends itself well to create your own. “I can’t remember if I cried, when I read psychiatry’s lies”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yDWvY_114gM

Report comment

Egads, and on the list of good music is of course “James and the disorders”, song called, “Bad Things Happen”.

It is listed under humour, but I think it’s quite educational.

Report comment

Good education is often humorous!

Report comment

And humour is good for our “mental health” too 🙂

Report comment

Since there is no such thing as “mental health” there’s no sense reading this, as it is misleading from the get-go.

Music is life-saving for many people. Revolution even more so.

Report comment

Long ago I wrote some blogs for MIA, and ever since I stopped, occasionally view what’s being written. As a psychiatrist who has long valued music and the arts for mental health, including my own, I read this article with some “chills” of myself. In my opinion, this is the best article on music (and with a suggestion towards the expressive arts and sports being of similar value) that I have ever read. As I was starting to prepare my notes for giving my weekly video on Society & Psychiatry, this one on The Arts and The Inauguration, this article is invaluable.

Looking forward to the third in the series and hope you branch out into all the expressive arts and sports in your analyses.

Stevie

Report comment

As I told Amy privately, I’ve always used music to “self regulate.” As a very (did I mention VERY?) anxious teenager, I would listen to music to calm down after a panic attack, and at times when I started to feel completely emotionally numb–it would “loosen” my stuck emotions.

I still use music this way. I’ve been suffering from some deep winter blues (some call it Seasonal Affective “Disorder,” but it’s more likely a response to less sunlight and a little thing called the pandemic). So I turned on my favorite Joni Mitchell album, Court and Spark, today to listen to while I work, and came upon these pertinent lyrics.*

My analyst told me

That I was right out of my head

The way he described it

He said I’d be better dead than alive

I didn’t listen to his jive

I knew all along

That he was all wrong

And I knew that he thought

I was crazy but I’m not

Don’t know

My analyst told me

That I was right out of my head

He said I need treatment

But I’m not that easily led

He said I was the type

That was most inclined

When out of his sight

To be out of my mind

And he thought I was nuts

No more ifs or ands or buts….

My analyst told me

That I was right out of my head

But I said dear doctor

I think that it’s you instead

Because I, I got a thing

That’s unique and new

To prove it I’ll have

The last laugh on you

‘Cause instead of one head

I got two

And you know two heads are better than one.

*apparently this was written not by Joni but one Annie Ross in 1952 (back when people still went to analysts).

Report comment

I like that you posted that Miranda.

I especially like this small part of her interview. The actual interview I believe was an hour long.

Where she talks about not interested in being defined, as she says, “the 3rd degree”. “misinterpreted”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fUu1MvnAecc

Report comment

Annie was in the singing group Lambert Hendricks and Ross. She died last summer at the age of 90.

I always knew “Twisted” as Joni’s song, but it is indeed Annie’s, and many singers have performed it. I always thought it was a delightful little “FU” jab at the whole middle class idea of what is supposed to be “normal.”

I wonder now how many girls I knew (when I was a boy) had to deal with the sort of emotional torrents that Miranda describes from when she was a teenager! I know one young woman (now a young mom) who still experiences this sort of thing a lot (she is embarrassed by it, I think, and likes to be alone when in the middle of it). But since roughly the 6 month mark of the lockdown in California, there is seldom a day goes by that I don’t cry pretty hard at least once that day.

Psychiatry (if it were a single being) would be sitting there grinning and rubbing its hands together, I imagine. A new flock of potential victims – I mean patients! – for our operation to chew up and spit out.

I like to listen to music from places where it is used as their primary route to health. Most of those places trace their musical roots to Africa.

Report comment

Miranda, that’s absolutely perfect! In my own life, music has carried me through all the toughest days and years — and I can’t imagine making it through this pandemic without it.

Report comment

l_e-cox, please share more about “places where music is used as their primary route to health”! Which countries or cultures?

Report comment

Well, I’m no anthropologist, but this is what I have seen: First, the more indigenous or nature-attached cultures tend to make music a big part of their lives. And if I can generalize, Africa has embraced music as a public community activity much more than the West has. I know that public performances have also been a big part of life in Bali. There are probably other places that I am less aware of. There is for instance the way street samba infuses life in the favelas of Brazil, particularly in Rio. I have also heard good things about Puerto Rico. In these places. music can be heard almost everywhere at almost any time. It tends to be celebratory rather than overly introverted and almost everyone is involved with it, including may part time or “amateur” musicians that help during festival times.

Report comment

As it happens, I’m touching on some of that in my third story in the music series, to run Feb. 14.

Report comment

I look forward to that, Amy!

Report comment