A recent study, published in the journal Environmental Justice, looked at the associations between historical redlining practices and present-day health inequities. The research team, led by Jason Corburn at UC Berkeley, found that residents in neighborhoods that were historically denied financial investment due to redlining policies were more likely to have high cancer and asthma rates in the present. Residents in these neighborhoods, examined across nine US cities, were also more likely to lack health insurance and endorse poor mental health.

The authors sought to contribute to the research that examines critical environmental justice issues affecting communities of color rooted in discriminatory policies. The researchers, Nardone, Chiang, and Corburn, write:

“Racial residential segregation remains a fundamental cause of health inequities, and redlining should be understood as a practice that left a physical and social imprint on urban health for generations. This study has attempted to explore one method for estimating the population health impacts today from historic redlining.”

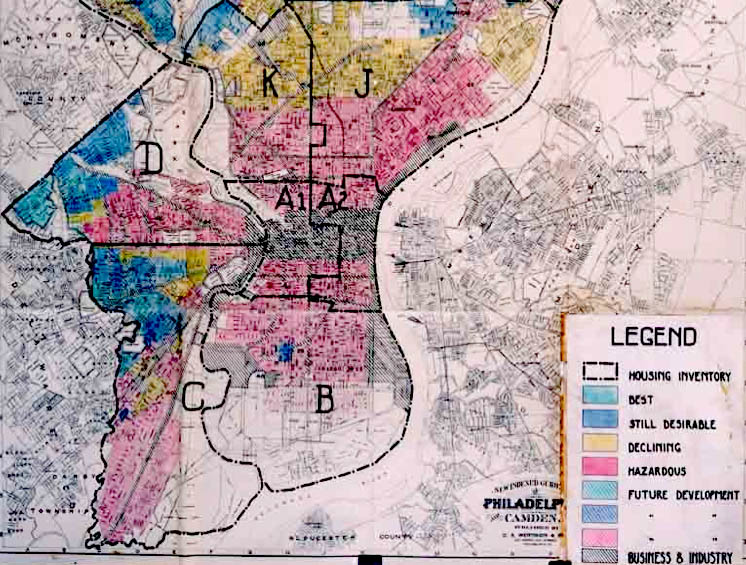

“Redlining” dates back to the 1930s, during the Great Depression, when black, indigenous, people of color (BIPOC) neighborhoods were categorized as “high risk,” restricting residents’ access to mortgages. On maps used by the private banking and mortgage industry, these neighborhoods were shaded red, hence the term “redlining.” Redlining originated as a practice of the government-established Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). Bankers and real estate professionals on HOLC committees graded neighborhoods on a scale of desirability.

Redlining was based almost entirely on race, Corburn and the research team point out. African American and immigrant neighborhoods were ranked “hazardous,” “high risk,” and least desirable. In contrast, neighborhoods that were predominantly white and non-immigrant were outlined in green, denoting desirability and permitting residents’ access to loans. Being denied access to loans thwarted black and immigrant homeownership and future wealth creation.

“Redlining was not the only discriminatory policy that adversely impacted urban communities of color,” the authors write. Federal housing and transportation policies, put forth as public health initiatives, led to the demolition of black and immigrant neighborhoods that were labeled as “unhealthy slums.” The authors articulate how these policies led to the systematized displacement and divestment of BIPOC communities:

“Taken together, redlining, housing, transportation, and other urban policies ushered in ‘white flight’ from cities, the widespread displacement of vibrant urban neighborhoods of color, and decades of urban decline.”

Redlining and other historical policies have had demonstrable effects, note the research team, such as racial segregation and environmental-justice related disparities that encapsulate the following: “persistent poverty and wealth creation, access to healthy food, mass incarceration, gun violence, qualities of green space, concentrations of pollution, and the determinants of health.” Despite attempts to prohibit redlining and other discriminatory practices, such as through the Fair Housing Act of 1968, redlining’s legacy has perpetuated structural racism, argue the authors.

What sets this study apart is that the researchers investigated whether these discriminatory policies in the past are associated with specific health outcomes today. Corburn and team distinguish the aims of the study:

“Although there have been a few studies documenting how redlining has adversely influenced general environmental quality, housing, and economic status of those in redlined neighborhoods, very few studies to our knowledge have investigated how historic redlining may be linked to current-day health outcomes in multiple cities.”

The team hypothesized that the relationship between redlining and current racialized health disparities still exists. They examined the estimated prevalence of health outcomes and behaviors, as defined by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in nine US cities: Atlanta, Chicago, Cleveland, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, San Francisco/Oakland metro area, and St. Louis. Publicly available census data were utilized to investigate HOLC-defined risk levels of neighborhoods. The CDC 500 Cities data set and the American Community Survey were used to examine health outcomes and demographic data.

A total of 14 health indicators were examined and clustered into three overarching categories:

- Health outcomes (asthma, cancer, congenital heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, mental health, and stroke).

- Unhealthy behaviors (binge drinking, current smoking, obesity, <7 hours of sleep).

- Preventative measures (lack of health insurance, pap smear, taking blood pressure medication).

The findings demonstrated that neighborhoods graded to be “higher risk” and redlined in the past are more likely to include BIPOC residents and residents who make less than the average income level today. The percentage of people of color who live in previously redlined neighborhoods (63.7%) was significantly greater than those who live in neighborhoods that received a low-risk grade (37.8%).

Overall, historical redlining was most strongly associated with significantly higher rates of non-dermatological cancer and poor mental health in the past month. Moreover, people who live in historically redlined communities are more likely to lack health insurance.

There was some variation within cities, as well as between them. For example, while there were no significant associations between redlining and health outcomes in St. Louis, Miami residents living in historically redlined areas were more likely to experience adverse health outcomes across almost all 14 indicators. In Atlanta, Cleveland, Miami, and the San Francisco-Oakland metropolitan areas, people who lived in redlined neighborhoods were twice as likely to have poor health than those who lived in non-redlined neighborhoods.

The researchers also utilized spatial mapping and found that redlining was associated with health risks related to pollution exposure in cities such as Los Angeles. The authors write:

“These maps suggest that redlining and other place-based factors likely matter for today’s distribution of population health, such as the locations of air pollution-producing highways and food outlets, but also that those living in previously low-risk grade census tracts may have better access to cancer screening services and/or treatment options today.”

Some limitations of this study are that it utilized an exploratory analysis to capture trends in select cities at one point in time. Therefore, results might reflect different findings if other locations and time points are observed. Also, additional factors that might explain the patterns presented in this study were not examined.

However, these findings provide insight into associations between redlining policies and health outcomes and behaviors today.

“Although our neighborhood-scale mapping is preliminary, it points to the need for a deeper understanding of the sources of intergenerational disadvantage that can adversely impact life chances,” the authors note.

“Thus, neighborhood inequality for African Americans is more multigenerational, pointing to the importance of historical policies, such as redlining, that have shaped place-based opportunities.”

Multigenerational negative health trends that map onto patterns of historical and systematic disinvestment of neighborhoods call attention to how policies have played a role in creating and sustaining the life-threatening marginalization of BIPOC communities. This specific study delineates the population health impacts of these policies and practices:

“Research now points to how community-level social inequalities act as stressors that adversely impact our immune systems, compromising health, and contributing to premature aging. The traumas from racially discriminatory policies, such as redlining, may be a source of toxic stress that is influencing the health of communities today.”

This research not only articulates “the long-term processes through which racialized environmental health inequalities came to be” but also sheds light on “what explicit policies are needed to reverse decades of inequitable policies and provide reparations.”

The authors conclude:

“This exploratory analysis suggests that redlining may have left an indelible imprint on the health of some urban neighborhoods today, and more must be done to understand and reverse this inequitable legacy.”

****

Nardone, A., Chiang, J., & Corburn, J. (2020). Historic Redlining and Urban Health Today in US Cities. Environmental Justice, 13(4), 109-119. https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2020.0011