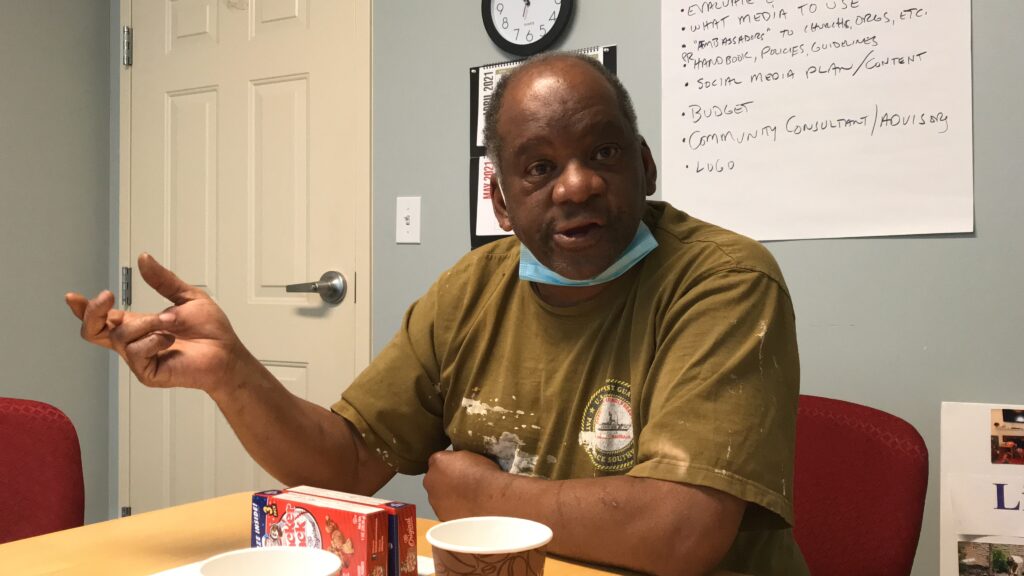

Carlton Brown, 66, has spent much of his life without a permanent home, having lived in the streets for long chapters and endured psychiatric hospitalizations in between.

He now has his own apartment in a supportive-living residence run by Joseph’s House in Troy, New York.

Mad in America asked if he would like to talk about his experiences. He agreed, sitting for two in-depth interviews. The resulting article, published below, was pulled together in his voice, using his words. It was approved by Carlton; he is the author of this piece.

— Amy Biancolli

T

his is a hell of a story.

It’s all about survival, because I’m not supposed to be living. I was homeless. Smoked crack. Drank. Went to the hospital, got volts in my head. I got stabbed, I got shot. I survived. And I finally came here, to my own place.

That’s it. That’s my whole life. Survival.

I was born in 1955. Most of my childhood, I was in a home — the Graham Home for Children, Hastings-on-Hudson. And I got beat. I went in about age 5 or 6, maybe 7, because my mother was an alcoholic. We lived in the projects in the Bronx — Bronx River Avenue. When I was young, my mother used to give me beer. I used to sneak it. I was liking the taste of it.

She tried, but she couldn’t take care of me. So the judge put me away in the Graham Home. Then I went to a foster house, a group home in the Bronx. After that I started getting snatched back and forth by different people, and I went from one place to another.

The mother of a friend that grew up with me in the projects — she knew me, so she took me under her wing. She took care of me, but she wasn’t buying me no clothes, so I was lookin’ kind of ragged. It was abuse. Then my father came to see me. He said, “Why you lookin’ like that?” So then he took me out of there, and I went to live with my father on the third floor of LeFrak City, a project in Queens. Then my grandmother took me from my father, and my mother would visit me there. Then from there, my father’s girlfriend snatched me to bring me back to my father.

Then my grandmother came and snatched me back from my father. I was in a tub — a tub with no clothes on. She knocked on the door, and I was in the tub, and she took me out of the tub to bring me back to her. I was a teenager, but that doesn’t make no difference. This was my grandmother.

Then one of my brothers took care of me in the Bronx. Then I got snatched from him and went back to my grandmother.

So you see, I wound up getting bounced everywhere. All over the place — here, here, here, here. All the way into my 20s, when I moved to Central Islip on Long Island.

Racist bosses and blow to the head

First I worked for a factory there. I was a welder, and I was living with my girlfriend Helen and our daughter Alicia. I also had two sons, Tito and Shawn, with other women.

I was an alcoholic at that point. I’m still an alcoholic, a chronic alcoholic.

So one day I went and got a bottle of wine. After that I didn’t have nothin’ to do with my time, so I walked down to the Central Islip State Hospital, the psychiatric hospital, just to see if i could apply for a job there. So I went and I applied in the maintenance department.

I became an assistant mechanic, and I dressed nice and neat in a maintenance outfit. But they didn’t like me — because I was Black, okay? They was prejudiced. And one thing after another happened.

First my foot got caught in the wheel of the machine that presses the sheets, and I had to pull it out. About a week later, they asked me to fix a machine, and I touched the wrong voltage, and it blew me back. After that, they told me to fix the dryer — the big, heavy dryer. Then, when I was inside the dryer, fixing it, they put the lid on it and pushed the button, so I spun around in the dryer. One of the Black guys saw me in there, heard me spinnin’ around, so he pushed the button and the gate opened, and I got out.

Then there was this crane with a hook on it — a hook to pick up a basket to take the clothes over to be washed. So the foreman pulled a chain, and the crane fell on me. I’ll say it again: The crane fell on me.

And I said they were tryin’ to kill me.

They made me go in the back and clean up all the garbage. Then the foreman said, you wanna go for lunch? So I said sure. He brought a case of beer, and we drank it by the window. He asked me: What do I think? Are they prejudiced? I knew they were prejudiced, but I said no.

So then one of the laundry machines broke. A dryer was hanging on a crane. The foreman said, “go under the dryer,” and I did — and he kicked the crane, and the dryer fell on me. And it crushed me. The whole big dryer, maybe 80 pounds. My whole body. I was under it. The guys that were washing the clothes went over, and they jacked it back up.

After I got out, there was a ladder standing there — and a hook on top of the ladder with a big ball on it.

The foreman told me to go push the ladder. When I pushed the ladder, the hoist came down, the hook came off it, and the ball hit me in the head. Okay? He told me to push the ladder to try to kill me. And the ball fell off the hook from the ladder. It swung. Swung. And hit me in the forehead.

I told you, this is a hell of a story.

They called an ambulance. The ambulance came. They said, your eyes are dilated. I was unconscious, like. They took me to the emergency room, but they didn’t understand what happened, and they sent me back home. They saw the bruise on my head, but they said: You all right, go back home. Because at first I was acting normal. I didn’t act out then — I was in a daze.

I started acting out later, after I went home. That’s when I became mentally ill. Because I had trauma to the head.

Back at the house, I got into an argument with my girlfriend Helen. I went out of control, and seven cops came. I was throwing shit down the stairs. I threw the table down the stairs. The crib, the table, the chair, the stove, the refrigerator. Adrenaline. I had adrenaline. Strong adrenaline.

I was outrageous, I was erratic. Abnormal, just doing things that you never seen before — screamin’ hollerin’ fightin’, bitin’. Paranoia, psychosis, memory loss. Don’t know where I’m at. Suicidal. Wanted to kill myself, wanted to kill people.

They didn’t know what to do with me

So they handcuffed me. They tied me down in the ambulance and took me to a hospital for the criminally insane — Kings Park, I think it was.

Because I didn’t understand my mind. I didn’t understand my symptoms I was getting from being hit in the head. But I was acting out. Tired. Frustrated. Confused. Angry. Agitated. Very argumentative. Violent. In the hospital they gave me Haldol and all this other stuff — Thorazine, Navane. Told me I was psychotic. At some point, maybe it was later on, a doctor told me I had schizophrenia.

There were other diagnoses, too. They was trying to see what can help me, right? But my damage was so fucked up they didn’t know what to do with me. But it all goes back to the blow to the head.

And the whole thing that was missing: I didn’t know myself. I had to understand the shit I was going through. The treatment I got — it didn’t do nothin’. The drugs did not help me, and they don’t help me to this day. But I had to realize my illness. I had to separate it out: This is why this happened, this is why this happened, this is why this happened, this is why this happened. The best drug that helped me was understanding. That’s the best drug.

I had to listen within myself. I had to analyze myself. You don’t analyze yourself, and listen to yourself, and figure out what’s right and what’s wrong? You ain’t goin’ nowhere. But all of that took a while — trying to understand my own mind.

And this was back in 1982. I was 27, and Kings Park was my first time in a psych hospital. I’d be sittin’ there with a cigarette, burning my hand. You could smell the flesh. My daughter came to see me, or she tried to, but they wouldn’t let her. So I had to scream at her through the bars on the window.

It was crazy. You had to watch your back — and I was learning from the violent people how violence works, see? So a guy stabbed a guy in the head with a knife. Then I got in a fight, and stabbed the guy in the eye with a knife.

Then they gave me shock treatment. That’s how they used to do us — a lot of shit goin’ on that people don’t know. So they took me downstairs into the basement, and they put a helmet on my head, and they put volts in me. This might make you behave. So I was goin’ down there, gettin’ volts in my head. Like, electric.

I was shaking. I had a gown on. The men in the little jackets were standing there when they turned the volts on, and I was very fearful. They were doing things they weren’t supposed to do to us. Torturing us. I was tortured. I went through torture.

Then they’d bring you back upstairs so you’d be sittin’ in the room with the doctor, and you’re out cold on Haldol. Like they take your body in there, and they just put you in jail. You just sit there like this, slumping, and the doctor says: You all right.

They gave me more psychiatric drugs. Put me to sleep. Then they had us sittin’ in a cell with rats and roaches. A block cell, two-by-four. And then the rats and the roaches — and you pee on yourself.

Living on the streets

So I sat there with piss and shit on myself for about three years, off and on, going in and out of Kings Park. When I had an episode, my counselor would put me back in the hospital.

When I wasn’t in the hospital I was living with my girlfriend and going to a mental-health center nearby — outpatient, in Wyandanch. I was also going back and forth to court for a lawsuit against the state hospital because of my head injury. The judge told me: “You’re on total disability.” This is why I won’t work now. Because when you mean “total” with a head injury, you ain’t supposed to work at all.

Eventually I won the case. I wound up getting a big settlement. I don’t remember how much, but it was a lot. I gave what I had to my father, because he took care of me.

Meanwhile I was going through my mentally ill shit, taking Haldol and peeing on myself in the house, on the couch, because I was sedated. So I slept with piss on the couch. Then things got complicated with my girlfriend. There was a whole blow-up, so we moved from Central Islip to the Bronx. I put my girlfriend and our daughter Alicia up with another brother of mine — I have seven brothers, three sisters.

Sometimes I stayed at my brother’s place with them, sometimes I didn’t. That’s when I first took to the streets in New York. I went back and forth — from the streets to the apartment to the streets.

While I was there, my brother turned me onto crack.

One day I was sittin’ there in the apartment, and I was lookin’ disturbed. Like, he was scared of me, you know — because I looked crazy. So he called my counselor in the city, and I went to Bronx State Hospital for a couple weeks or a couple of months, I don’t remember. Then I went back to the streets, because I was used to the streets. I was drinking and cracking, eating out of garbage cans, living in the subways, at Grand Central Station, Times Square, Park Avenue. Ate at the soup kitchen. Then I went into a shelter on 42nd street, and I stayed there about six months.

When I wasn’t on the streets I went back and forth to Harlem Hospital Psychiatric Center. I went to other hospitals, too — to Bronx State for circulation problems, Bronx Lebanon for other things. I also had surgery on a broken ankle after a car hit it when I was crossing the street, and I went to Bronx Montefiore for an operation.

Then I came out and I took to the streets again, and slept in a dumpster.

I got arrested for crack and alcohol, and I went to Rikers Island. Seven or eight times I went there, and at one point the guards broke my arm. Every time I got out, I’d go back to the same spot where I would be drinkin’ and hangin’ out — in the Bronx, at Gun Hill Road, the train station. I’d stay there, piss there, shit there, drink there with the winos, crack there. Then the cops would catch me, and I’d wind up at Rikers Island again. Or I’d go back to the hospital.

This was all the late 1980s, maybe 1990 — I don’t know. All I know is I was out there, back and forth, back and forth. That was it. I don’t look at years. There’s no such thing as years. It’s just survival. I just stayed in the street. When I wasn’t in the hospital, when I wasn’t at Rikers, I was on the streets. That’s my life. That’s the story. When did it hit me that I was homeless? It never hit me. It don’t hit me now.

I appreciate where I’m at now. That’s it.

Surviving on the streets

Sometimes I would go into the woods, and I would sleep there. I had a gun, and when I heard somebody in the woods, I would shoot the gun. That’s right — I would shoot the gun. That was on University Avenue. Because it’s either them or me. Survival. Either them or me. I don’t know if I killed somebody — I don’t know. I’ll never know. But when you’re out there on that street, it’s either you or them.

And I knew they would kill me. I got shot once by somebody who was homeless — shot in my stomach. But why wouldn’t they? You go in the dark up the street, and you see what the fuck happens to you. You think they gonna worry about your ass? I could have died. All I know is I survived.

So shooting the gun — I don’t feel nothin’ about it. No. Because I had to survive. Simple.

One time I walked from the Bronx to Manhattan to Brooklyn to find a psychiatric hospital. It was snowin’ out there, maybe four or five feet, and I walked through it with no shirt, no shoes, no underwear, no socks. I had to walk to survive. I got jumped on Brooklyn Bridge by some guys who tried to throw me off. But I kept going. I did it because I was looking for a new hospital. I didn’t want to go to Harlem Hospital again — I’d been there. I wanted a new hospital. I was searching for help.

I left the Bronx around 4 or 5 o’clock in the afternoon and I got to the hospital in Brooklyn by midnight. They didn’t know what the fuck I was. They didn’t understand how the fuck I walked from the Bronx all the way to Brooklyn.

I stayed there about three days. After that they put me back on the street. They didn’t give me no place to stay, so I had to walk from Brooklyn back to the Bronx. They didn’t give me no bus fare or nothing — they just threw me in the street.

For a while I stayed with this woman Carol, my girlfriend. But then I started drinking, and she couldn’t handle me no more, so my son Shawn came and picked me up — and he brought me up here, to Troy, because I was outrageous. That was six, maybe seven, years ago.

Soon enough I was bouncing again, doing the back-and-forth. I was drinkin’, and then I was smokin’ reefer with his stepson, and then he got rid of me. So I was homeless again. I went to the shelter across the street. I stayed about two months. Then they was gonna give me a place over here, with the permanent housing, but Shawn needed to move. And you know how fathers are. So I used my subsidy to get an apartment with him over in Rensselaer. So we were splittin’ the rent, but then he took advantage of me and started tryin’ to control me.

And he threw me the fuck out. Simple. He locked me out of the house. Put that down: He locked me out of the house. And I was payin’ rent.

I took to the streets. Ain’t nothin’ wrong with the streets. I’m a survivor.

Then I met this girl and moved in down the street with her. The place had no heat. No electricity. We got in an argument, so she left. A counselor came in and said: You can’t live like this. So I moved down to South Carolina and lived with my niece for a little while. I didn’t like it too much, so I used the mental health system by acting up, and they put me in a place. A nice place. They gave me good sandwiches. After that, my other son, Tito, invited me to Detroit. I lived with him for three months, smoking reefer.

And I wound up in the streets again. Just livin’ in the street, sleepin’ in the street. I also spent about two and a half months with my ex-wife Sherry until things got bad, and I went through a lot of bullshit. I went to the hospital in Detroit, too. So the same kind of back and forth. Same thing.

All in all I was out there about six months, then I came back here — to Troy. I went back to the shelter and stayed there for six, seven months. From there I came here, you see what I’m saying? I came here, I came here.

Hitting my peak

This is the best place I ever had. Why? Because when you live in the street, it’s no joke. I ate out of the garbage. I ate rotten food. I waited for a restaurant to donate food. I slept in dumpsters. My best friend was a rat in the tunnel. I slept in the tunnel, so I had to make friends with the rat — put that down.

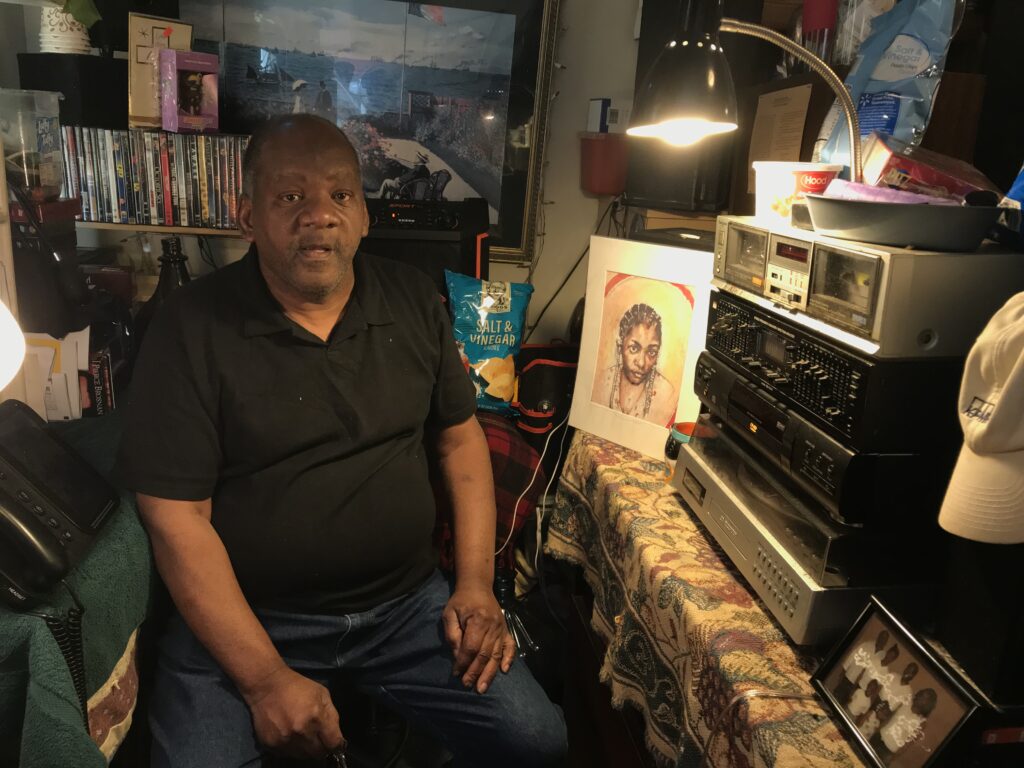

Sometimes people don’t understand why I have so much shit in my place here. I got a lot: speakers, potato chips, soda, a lot of food. Because I’ve been homeless — you see what I’m sayin’? — and I appreciate where I’m at.

I really enjoy having my own place, because I never had my own. I love to be in my place — I call it my house. I love to be in my house. I’m living with my TV. I put my VCR on. I’m playin’ my music — jazz, classical, African, Italian, Spanish. Everything. I got cassettes, I got CDs, I got movies. A full freezer, and my bathroom is nice and clean. Towels. Clothes. And I clean my house all the time. I don’t hang out in the street like I used to — I realize if you’re in the street, you can’t blame nobody but yourself when you get in trouble.

I’m 66 now. I feel good.

Being here means a lot for my mental health. It plays a big part, because it’s less stress on your brain. And I learned not to be angry, okay? I learned how to speak my mind, and I don’t care how you feel. I tell the truth. I take a lot of shit but don’t react to it. I’m a very calm person, but I speak my mind. I stand my ground.

The last time I went into a psych hospital was two or three years ago. Up here — Samaritan Hospital. In and out.

I’m on all kinds of medications. I got a nurse coming every Wednesday, and she fills my pill box. I got a heart problem, I got diabetes, high cholesterol, hypertension, water in my feet, allergic reactions. I’m allergic to fish. I got gout. I had a stroke in my left leg, and an aide comes to help me take a bath. I got everything.

And I’m still on some psych meds now — mood stabilizers. Not on Haldol any longer — I got off it. Don’t know when. Did I have withdrawal? I could be havin’ it now. Who knows, right? I don’t know. I’m gonna be honest with you, I don’t know.

And I don’t care about livin’ now. Why? I can’t answer that — I really can’t. I’m being honest with you. After all the shit I’ve been through, I don’t have a hard time, but I don’t care about life. Somebody kill me today or tomorrow, I don’t give a shit. I hit my peak already, right? Let’s be real: I hit my peak, and that’s livin’ here. If you’d been through the shit I’d been through, you wouldn’t give a fuck. Nothing else could happen to me. I could walk the streets. Somebody could kill me. I could get hit by a car. I don’t give a fuck.

You would know, if you had to go through it.

What I want people to know

You want to know more? Go out in the street and find out. Go the fuck out there. All you gotta do is you walk out that motherfuckin’ door. You’re homeless now — that’s homeless. You don’t know if you’re gonna survive. Somebody might shoot your ass.

So what else do you want to know? I did good. I did very good to survive. That’s the end of my story.

I’ve lived out my life, and I’ve eaten out of garbage. I’ve had diseases, everything. What else can happen? And now I’m living here. So let’s be real about this shit.

What I want people to know: Be thankful for where you at.

What else I want people to know: Every mentally ill person is not crazy. They’re very observant, they’re very intelligent people in one way or another. They might be talkin’ to themselves, but they might listen to you another way. Stop judging mentally ill people. Mentally ill persons are the best persons to be around. I might say something crazy to you, but if you really analyze it, it makes sense. Every mentally ill person has their good ways of communicating — you just gotta listen to them.

People with mental diagnoses, people who live on the streets — they’re regarded as a piece of shit. That’s how people treated me when I was on the streets: a piece of shit. I felt sad, I felt hurt, I felt they didn’t give a fuck, I felt confused. They don’t treat you as human at all.

What would I say to people who run the mental health system? I would say they need a person like me to talk to. They need to hear from experienced people like me, because changes should be made.

And I would tell them to take it very seriously. To be patient with mentally ill people. Don’t take your personal shit out on them, because that aggravates the situation — and I’ve been through that experience. I feel like they’re not doin’ nothing to help people. I know they’re not, because if I was in that situation, I would know what to do. And what would that be? Caring.

If you don’t care, if you have the wrong attitude, and you’ve never been there, then how the fuck do you know? This is what I would say to them: How would you know? I’m speaking my goddamn mind, now. And if you ignore it, that’s on you. But I’m just letting you know how I feel about the situation with the mentally ill.

Put it like this, put it like this: Anybody gotta ask questions, ask Mr. Brown. No, for real. Ask him. Ask him — he got the right answers for you. A lot of people got closed minds about the mentally ill. I can make them aware. If somebody sees my goddamn story, they should be able to say, “I want him. I wanna hire him, because I know he’s gonna do the right shit.”

Mental health, the way people talk about it — it doesn’t matter to me. For real. Mental health is bullshit, unless you’ve lived the life. You know what mental health is? Going through experience. That’s what mental health is. The rest of it — it don’t mean nothing. You can’t help me that way. You gotta live the life to know what it is. It’s not mental health. It’s survival, I’m telling you. You gotta believe me. This motherfucker went through it. The answer to mental health is survival.

You don’t survive, you’re a dead bastard. The last word is survival. That’s it. It’s over. The interview is over.

This was a hell of a goddamn story.

From our inception, Mad in America has sought to provide a forum for people whose lives have intersected with psychiatry and its treatments to tell their stories. However, we have always known that this didn’t provide a forum for the many, like Carlton, who wouldn’t be prompted to write their stories, or who would even know about Mad in America. With this story, we are launching an effort to provide a forum for those “Unheard Voices” that need to be heard as part of any societal “rethinking” of psychiatry and its treatments.

Report comment

Dear Carlton

Wow! thank you for sharing your stunningly powerful story of survival. I am actually feeling pretty speechless reading about what you went through. Your unheard voice – I hear you and you moved me, big time. -thank you

Report comment

Carlton, I think you have it and the system figured out, and I’m convinced that you are

your own boss.

Your story is real, the treatment you received in the home, work and psych environment was simply others acting out their ignorance on you.

I always say, wrong place, wrong time, with the wrong people.

Thank you so much for doing the interview with Amy and thanks MIA for going above and beyond to get the real scoop.

Carlton, you’ve made some very powerful statements, profound really.

Report comment

I started reading your story, Carlton, and tears came to my eyes – the injustice of it all, is just heart wrenching. I had to stop reading, since I’d just finished a walk in a park, and was sitting at a picnic table in that park, and I didn’t want to cry in public.

“The best drug that helped me was understanding. That’s the best drug.” Words of wisdom, Carlton. And I agree, “the truth will set you free.” The truth is what saved me from psychiatry, too.

“Let’s be real: I hit my peak, and that’s livin’ here.” I’m quite certain this is evidence that housing is more important to provide, than ANY “mental health” service or drug.

Thank you for sharing your story, Carlton. I’m finishing the cry that I started in that park, as I write this, in the privacy of my home. I’m glad you survived, and I hope you may retire – in peace – in your beautiful “house.” And I pray God blesses you and your family.

Report comment

This story comes through loud and clear.

Is this guy “mentally ill?” How would YOU react to those experiences? He survived to speak honestly about what happened. I’d say he is one of the saner ones.

The sociopathic co-worker, the abusive hospital attendants and psychiatrists. Is this our “normal?” Those people, if anything, had bigger mental health problems. Why weren’t they the patients and Mr. Brown their keeper? Could it be this is a planet that has been turned on its head? Where good works and honesty are looked down on, and rape and murder applauded? It seems so, sometimes. Are those of us lucky or sane enough to have calm productive lives a minority on this planet? Sometimes I wonder. In any case, this story gives us some idea of how far we have to go.

I like his admonition: “The best drug that helped me was understanding. That’s the best drug.”

Report comment

Not sure exactly what the point of printing this is, other than to demonstrate that MIA has some Black contacts (sorry, had to say it). But if the purpose is really to provide a “forum” what I’m basically taking away from the discussion is a) “Somebody kill me today or tomorrow, I don’t give a shit”; b) “Mental health is bullshit”; and c) “You don’t survive, you’re a dead bastard. The last word is survival. That’s it. It’s over. The interview is over.”

I empathize with Carlton and admire his insight, which is shared by many others who have been imprisoned, psychiatrically and otherwise, and forced to live on the streets. It is indeed a question of survival. But nothing here is the sort of crisis that can be addressed by “rethinking psychiatry”; psychiatry can only get in the way, as Carlton makes clear. What he actually does very well is make a circumstantial case for revolution.

Report comment

I partly agree, but I also think it is a fine piece of working class writing showing what life at the bottom is like and how the state oppresses the poor – and you don’t get much of that in mainstream media. As such it is one of the best pieces on the site imho.

It is a piece that would not be out of place in the UK Lumpen journal. https://www.theclassworkproject.com/lumpen

Report comment

Pointing out his blackness is sort of the problem. It is OK MIA has “black contacts” and gives a forum…again what is the problem?

I think what this man’s story shows is the fundamental striving for humanity. He can show his shortcomings and those powers above and beyond that just were barrier. I could not empathize every decision he made in the past but I could see his struggles. At the end, I was on cheering at his delight in being independent in his 60s with all these health issues and giving his universal given wisdom whatever it might be.

Report comment

Deep respect for you Mr Brown and the incredible heroe’s life journey you have lived – thank you for sharing your story. So many could not have survived as you have done.

If there was ever a compelling case for an ‘unconditional basic income’ – to end the ‘survivalism’ 24/7 hyper-competitive neoliberal capitalist culture that forces humans to compete against each other, surely this is it?

It would be powerful to see your life story made into a movie to educate so many – especially those psychiatrists who think the solution is to numb people’s trauma and pain with ‘early Big Pharma drug intervention’.

Well done Mr Brown and to MIA.

Report comment

Thanks, Mr. Brown for doing the interview. Safe housing, regular meals and understanding are critical to an improved mental state. So much money is spent on programs that are detrimental to people’s Mental Health. The money would be better spent on safe housing and food.

There needs to be a better understanding of mental health problems before Mental health programs that do help can be developed. Mr. Brown and others with lived experience can increase understanding if people listen.

Report comment

Bravo Carlton,

For telling your story. I think you have a lot to teach other people, and I hope there is more to come for you, in terms of people paying attention to your deep and hard-won wisdom.

I can relate to so many aspects of your story, (although not all of them).

You…I can listen to.

I tried to have something published here last year, but it was considered too long. I am glad the editors have altered their standards. Some lifetimes cannot be represented in a quick, condensed fashion. All of that pain, and all of that wisdom, needs to come out the way it needs to come out. What a mighty effort. My heart breaks for what you went through. And sadly, the system fails people every day.

I deeply relate to ‘years meaning nothing’ and ‘not knowing if I was even in withdrawal’. Time gets lost, and it becomes simple survival. That’s all that’s left. You don’t know what’s up and what’s down. I understand your gratitude for having a home of your own, but also, on some level, for not being too ‘attached’ to your life, because of what you have been forced to go through before.

May your days remain safe, comfortable, and happy. xx

Report comment

I met Mr Brown the day he moved into his apartment. I have heard his story in bits and pieces over the last 5 or 6 years. He is one of the most self-aware people I know. He is truly a survivor!

Report comment

Wonderful interview, rough experience. “They don’t treat you as human at all”: yes, that’s the point. And they feel OK, entitled and even meant to do so, push you down and beat you while you are still on the floor. Caring, so many worlds, galaxies even, apart from the real situation. Wishing Mr. Brown is still enjoying his peak moment, going up and beyond.

Was the “Unheard Voices” series of articles cancelled?

Report comment