Dana Becker is professor emeritus of social work and social research at Bryn Mawr College and has practiced as a psychotherapist for over three decades. With a doctorate in psychology and a master’s degree in social work, she has been an equal-opportunity critic of both fields in her work on the effects of therapeutic culture on women in the US.

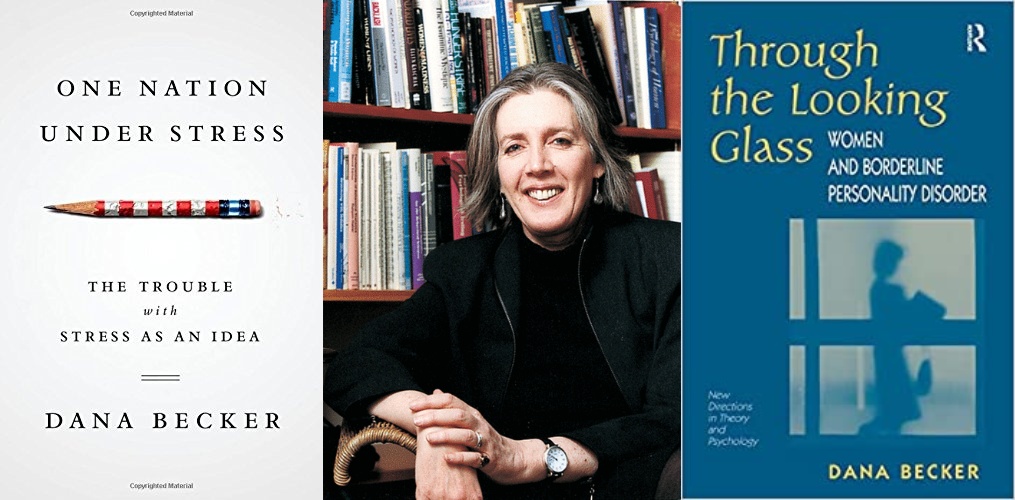

These themes are explored in her books, Through the Looking Glass: Women and Borderline Personality Disorder (Westview Press, 1997) and The Myth of Empowerment: Women and the Therapeutic Culture in America (NYU Press, 2005). Her most recent book, One Nation under Stress: The Trouble with Stress as an Idea (Oxford University Press, 2014), tackles the effects of the therapeutic culture through an examination of the ideological work currently performed by the stress concept. Her work has received awards from the Society for the Psychology of Women.

Becker is known for her work on the use of borderline personality disorder to medicalize women’s problems. She has also advanced some significant criticisms of the way we talk about and deal with stress in our society and noted how feminist psychotherapy had been weakened in its revolutionary potential.

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio of the interview here.

Ayurdhi Dhar: Could you briefly tell us what ‘therapeutic culture’ is and your concerns and criticisms?

Dana Becker: It is the culture we are all swimming in, infused with psychological concepts, values, and institutions predicated on those.

In therapeutic culture, the psyche is the principal object of our attention. The psychological is seen as the main source of problems in our society, and the health of our “psyches” is the ultimate goal. These shared assumptions about the psyche and its importance, and the importance of the self, shape our values, behaviors, and even institutions.

This emphasis on the psyche and the self makes the world, society’s problems, and structural and institutional problems less visible to us. Our American reliance on ideas about individualism also shapes therapeutic culture.

Dhar: How do you bring this consciousness about therapeutic culture into your work as a therapist with your clients? How does this influence your work?

Becker: We have to bring social context into therapy, but we cannot stop in the therapy room. A 45-minute session does not a world make.

For instance, women whose problems have long been medicalized see their own problems as medical problems, but we as therapists have to see all problems. It doesn’t mean that if somebody suffers from clinical depression, we’re not going to help them get medication. But as a family therapist who has worked a lot with women, I will ask not only about the family and relationship context but also understand the client’s perspective on the world and on gender—how women see themselves.

I have spent several decades doing this work, and when I started, nobody ever came in saying, “I’m bipolar.” You never heard that. Nobody was doing self-diagnosis. As I continued to work, women would come in and say, “my mother thinks that I’m bipolar.”

I don’t like people calling themselves a diagnosis. They don’t say “I have bipolar disorder” these days. They say, “I am this, and I am that.” In the 1980s, there was a book called Mood Swings, and some clients and their parents or partners would read these things and immediately say, “Oh, if you’re angrier this day than the last day, that must mean you have mood swings, and that means you’re bipolar.”

For me, as a therapist, it is about finding out the context in which those ideas arose. What’s going on there? Sometimes the woman feels justifiably angry, but her partner or parents say, “there’s something wrong with that, and that means you have mood swings,” which means a diagnosis. This is how emotion gets medicalized.

I am not saying there is no such thing as bipolar. When you take a position like this, people always criticize; it is not as extreme as people assume. As a therapist, you have to delve deeply enough to understand the context of what the client is bringing.

Dhar: So, therapeutic culture is not just psychiatry but a larger societal and cultural narrative that exists, changing our self-definition. I have students who come in saying, “I am this or that (a diagnosis), but my therapist won’t give me a diagnosis, but I know I am this.”

Becker: There are other concepts, too, not just diagnosis. I had clients saying, “I’m feeling really terrible this week. I’m having a pity party.” Where do women get the idea that when they’re sad or upset about something that’s going on, they’re being self-pitying? The pity party aspect is denigrating.

For a therapist to not be curious about that is problematic. If I understand something about gender socialization, then I see that that woman bringing that idea to me brings a whole world of gendered associations.

Dhar: The first thing that we do when something happens is look inwards and look at our emotions and not bigger, external, systemic issues. Why do you think these psychologized or therapeutic narratives have become so powerful and pervasive? Is it a matter of who they benefit?

Becker: First, there certainly is a benefit for the psychological professions. There is a benefit in the medicalization of human problems. There’s no question about that. When the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual first came out, it was less than an inch thick, and now it’s so bloated that anything can be called a psychological problem. The professions have benefited greatly, and the number of psychological professions has proliferated. You have professional counseling and social work, which used to be a different kind of profession.

The other part is about the gendered nature of ideas about emotion because women have always been the primary candidates for psychotherapy, self-help books, and psychological advice. With Oprah and others, it became popular to talk about problems that had been hidden from public view. Also, there is the veneration of science—from the 19th century onward, there has been a tremendous scientization of all phenomena. This also influenced medicalization.

Freud himself never wanted psychiatry to become a medical profession. But, in America, it was decided that you had to become a medical doctor to become a psychiatrist.

Dhar: Recently, you wrote about the absence of context in feminist therapy, which, you write, has become toothless. Could you elaborate?

Becker: In a sense, there is no feminist therapy today, no people who call themselves feminist therapists. There are people who are feminists who do psychotherapy, but that’s different.

In the beginning, there was consciousness-raising—a very middle-class, white phenomenon. This was a critique of therapy for women—do we really want people to look inward rather than outward for the source of their problems? Fairly quickly, the ideas that consciousness-raising brought to therapy, which was bringing social context into the therapy room and helping women to achieve greater activism outside the therapy room, quickly became subsumed as professionalization took over.

It was a fairly short period. Today for women, trauma has become the watchword. Trauma and women have become a bundle that a lot of therapists who consider themselves feminists see together—”Let’s figure out how you’ve been traumatized.”

Now, talking about traumatic events has become much more destigmatized, and so have psychological problems, which is very helpful. Even back 1980s, it was rare for therapists to ask a woman if she’d been sexually or physically abused. Now it’s routine. It is good news for these problems to come out of the closet and for the social and societal context of psychological problems to be visible.

Having said that, when everything in the world is labeled traumatic, there is a loss of meaning. If I’m traumatized because I have too many text messages as opposed to having been a prisoner of war… These are things that are labeled traumatic these days, and the idea of trauma has lost meaning.

The other problem is that those who practice therapy, particularly in America, assume that every disaster induces trauma in everyone. This is not the case. For instance, after the tsunamis that happened a decade ago, American psychologists went over to offer psychological help to the victims of trauma. The people said, “we don’t have a house, warmth, and family has no food. And you’re talking to me about being traumatized.”

The events of 9/11 were cast tightly within the trauma narrative. Even ten years later, the American Psychological Association’s American Psychologist had to put out an entire issue which was a research apologia for all of the psychological work that had insisted that everybody was going to be traumatized. Everybody who had witnessed it, or seen it on TV, or the exposed children—everybody was going to suffer. The research found that this was actually a very small percentage of the population. But now, when research is done, a high percent of the population will say that they’ve experienced at least one or more traumatic events in their lifetime.

Dhar: It ties with Ian Hacking’s idea of the looping self—a concept in a popular narrative that changes your self-definition and then your experience. I wondered if trauma is the next big thing after the medicalization narrative. Can you give examples of how specifically trauma has been co-opted and used to further medicalize women’s problems?

Becker: In the DSM III, events that were causative of PTSD had to be considered outside the realm of human experience. Many feminists agitated for these criteria to be broadened so women’s experience of sexual and physical abuse would be included. Initially, I was really taken with this because I was studying the borderline diagnosis, which I can’t abide by, and PTSD was the only diagnosis with actual external situational causes. I thought, “this is wonderful.” So, we expanded the diagnosis. It changed my position.

I did a complete 360 and was horrified at how often the PTSD diagnosis was just slapped on women. They didn’t meet all the criteria. It’s not to say we shouldn’t take note of the abuse and its ill effects, but it became another tool to medicalize women’s suffering. This is how I think about the trauma narrative feeding into the PTSD diagnosis.

There was a terrific bit of research done by Jeanne Marecek and Diane Kravitz back in the nineties where they interviewed those who called themselves feminist therapists. They were saying, “This is the only diagnosis that I ever give. It’s not that I give it to every woman. I tell people, you have PTSD, and this is a normal reaction to trauma.” First of all, PTSD symptoms aren’t a normal reaction to trauma; otherwise, we wouldn’t be calling it a disorder. PTSD as a diagnosis had been much broadened.

Dhar: PTSD being a normal reaction to trauma doesn’t translate when we look at other places in the world.

Becker: No, culturally, it’s just absolutely terrible.

Dhar: And the second issue is we necessitate verbalization—that talking about trauma is the only healthy way to deal with and process it. You have to go to a professional. It just doesn’t work like that.

Becker: No. As cultures, we decide what is normal and what is not. Derek Summerfield talks about this—in a society, we decide what we say we should have to endure or not.

After the bombing of London, the Londoners were not calling themselves traumatized. There wasn’t any language, the there was no narrative for that. There was an attitude of keeping calm and carrying on and all that. Even in war, shell-shock was considered a humiliation. All of this was terrible, yet it was so different from our 9/11 response—a different discourse.

Dhar: In One Nation Under Stress, you write that the Psy-disciplines focus on the effects of stress, on being stressed out, and not always the causes. You write our individualist culture plays a part. Could you say more?

Becker: Making a bridge between trauma and stress, both concepts now share the same kind of problem. The cause and effect are conjoined in a way that makes them one, but it’s the emotional response that we focus on. So, the thing that stresses you out and your reaction to it are both ‘stress,’ but we focus on the feeling of being stressed.

In the book, I talk about this crazy American idea of balance. Women are targeted for this stress discourse. For instance, you are a working mother doing shift work or a professional woman. This discourse of balance applies to everybody equally, even though the stressors are quite different. The professional woman who is a CEO can have a nanny and is not in the same position as the woman working crazy shifts with no notice and thus no childcare. But we’re supposed to achieve a balance between what we’re doing out there, what we’re doing in the family, and take really good care of ourselves, no matter what the outer stressors are, what the context of our lives are. The idea is that if we can do that, we won’t be stressed out and angry and will be able to take care of everything.

Care has been a women’s province in this country, particularly since industrialization. As middle-class women flooded into the workplace in the 1980s and beyond, the expectation of care did not change. But now, the expectation of balance has become another weight on the shoulders of women.

I can use myself as an example. I never called myself stressed out the entire time. I had no money. I was a single parent. I was doing my doctorate and taking care of my son, a dog, a school turtle, everything else. And my expectation was that I did everything perfectly. So we moved on to this idea about balance that we should be able to juggle multiple things. If we can’t, it’s our fault. We blame ourselves, and we should buy more commodities to help us. If you’re poor, you don’t have the time, money, or support to do the caretaking things that middle-class culture tells us we should do.

Dhar: That’s where the narrative of self-care enters. I have to break it to my students that candles in a bath will not solve problems that emerge from poverty.

Becker: And when we call it stress, we then flatten this out. If we say we’re stressed, then it’s my problem to solve.

Dhar: So, stress is one way to individualize this? And then the diagnosis from borderline to PTSD are also ways?

Becker: So many of the women who are diagnosed borderline are women who have suffered extreme abuse, neglect, and invalidation. Stress is a non-diagnostic tool for those women who, as many of us do, take our cues from popular culture.

Dhar: Yes, I have a three-week-old baby, and whenever I feel overwhelmed, my mind goes to postpartum depression. I have read so many criticisms of the diagnosis. Plus, I have a broken ankle, I am away from home, and need to join work. But despite knowing about these important external factors, even as a critical psychologist, postpartum depression is the concept that keeps coming back into my head. Even if you are aware of them, the power of these narratives is strong!

Becker: If we’re just stressed out, we blame ourselves for not taking better care of ourselves. Then there’s no need then to go outside and ask, “Why are we still the only Western industrialized nation that does not have any paid family leave?”

And the most stressed-out women don’t have time for activism. This is another part of the problem, “I’m too stressed to get out there. I don’t have time to call my congressperson.” It’s a way of easing our consciences. We can say, “I’m stressed out; I’ll put on some candles, take the bubble bath, eat more kale smoothie.” There are women in our country who don’t have the option to do those things or have any help. And as you suggest, we’re not looking to the community as you would if you were back in India.

Dhar: There is a recent conversation around structural determinants of mental health, how things like poverty, violence, racism can be psychologically damaging. I wonder if it’s going to get co-opted and absorbed—if it’s just paying lip service, and the answer is again individual therapy. What do you think?

Becker: That’s what worries me. See what’s happened in poor neighborhoods in the public school system. We understand discrimination, the effects of poverty, of bullying. We know these things contribute to a child not doing well in school or acting out. What do we do? We call the mother, only the mother.

It’s the mother’s problem. She has to take the child to therapy, who is often not a family therapist. So, the child is with the therapist, who is very understanding for 45-minutes a week and then goes back into the same environment. So, the mother doesn’t have support or understanding of what’s happening in the therapy because she’s not included in that.

Studying stress, I found some really crazy popular articles about poverty and depression. This really worried me—seeing how these things are getting co-opted by the medical establishment—”Let’s treat the depression. So many people who are poor are depressed.” It’s the same as the trauma and stress problems—the external cause becomes shunted aside for the emotional after-effects.

It’s so much easier to deal with the effects. We don’t have to deal with discrimination, poverty, racism, with differences in tax dollars going to school in poor neighborhoods. It creates a perfect environment for us to individualize these problems.

Dhar: Since we are talking about ignoring larger systemic issues, let’s move to positive psychology, which used to be very popular. You have raised concerns about positive psychology. Could you elaborate?

Becker: Just like with PTSD, initially with positive psychology, you would think psychology is turning to context. Jeanne Marecek and I argued that positive psychology bolstered the psychology profession at a time when great inroads were being made through managed care, social workers becoming therapists, the professionalization of counseling, etc. The problem was that positive psychology is just as acontextual as any other form of individual psychology.

Positive psychology is yet another of the many ‘adjustments psychologies’ that we have loved in America. By adjustment psychology, I mean those movements like the mental hygiene movement in which the goal was to produce these happy, healthy, “well-adjusted” individuals. For example, a woman who can take care of herself and her family without a lot of complaints and anger. That would be an ideal adjustment.

So the problem is that if you talk about “what kinds of families result in children who flourish,” and that’s the quotation from Seligman about positive psychology, you can’t do it without thinking about the environment, the institutions, and social context. The nuclear family is much too small an environment to look at.

I’ve been trained in multidimensional family therapy, which looks at the much larger context of families and their connections with broader institutions. We can’t simply focus on the dynamics of a family and then say, “We’re going to help that family to create wellbeing among children.”

Another example is Martin Seligman’s huge contract with the United States government to bring positive psychology to the military. For example, you have a soldier who’s going off to war, who is afraid of being killed, who’s going to presumably kill other people and watch them die. You’re going to inoculate them somehow with positive psychology against these horrors. But we don’t talk about war or male socialization and how we create warriors. We’re just going to train people to be more resilient.

The concept of moral injury is another internalization of a much larger problem. When the military talks about moral injury, it’s individualizing a problem that’s created because there is the existence of war and those political decisions. We only talk about the moral injury to soldiers, and anything that uses the medicalized language of injury brings us into the land of trauma. Again, our entire discussion, in many ways, just curves in upon itself.

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

“I am not saying there is no such thing as bipolar. When you take a position like this, people always criticize; it is not as extreme as people assume. As a therapist, you have to delve deeply enough to understand the context of what the client is bringing.”

“Bipolar” is as problematic for me as “Jesus.” The culture is polluted with both. And for me there is a connection. Victim of criminal psychiatry at a Catholic hospital built by the nasty nuns of my youth that I rejected. Part of a larger psychiatry-as-weapon, as if I lived under Putin or China, attack. Yes. True. I’ve not read any other story like it, and I look.

Some grasp and others abuse with the label. But everyone has heard it and assumes it’s as real as air. I was never evaluated but got the label in the emergency room by a man I never met.

I need professionals to tear down the word. Bipolar by Jesus is way too much to bear, meets the definition of torture and why should I be held in torture? Jesus was the original psychotic, maybe the original bipolar!!!

Report comment

I am terribly sorry that you feel that way about Jesus. Jesus saved my life from the evils of psychiatry, etc. It is very upsetting to me to hear that there are those who consider Jesus, the most perfect being to walk the face of the Earth, as having some devil-conceived, human sinfully adopted supposed illness. The fault is not in Jesus. It is in those of us who accept these diagnoses about ourselves that are false, and evil. I, too, did that at one time and it almost cost me life. But I like said earlier, Jesus saved me, and I thank Him every day for delivering me from psychiatry, which is nothing but pure evil and the work of the devil. Calling Jesus as the first bipolar is not a joking matter. Jesus is the One who saved from this evil. Thank you, Jesus and Thank you.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

And if hearing words like “traumatized” and “resilience” bother Dr. Becker so much, she oughta try living on the receiving end of one of her own “diagnosis” –

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

The author uses circular logic to describe circular logic. And then she points her finger at everyone and everything but herself and her own profession which to a great extent feeds the problem –

Report comment

I’ve been reading Jorg Friedrich’s nonfiction masterpiece The Fire. So my ears perked up when you mentioned The fire bombing of London in WWII. And your description of Londoners response. And then your comments about war and Warriors. I just commented recently on Robert L. Moore’s book Warriors, King, magician, lover. Another masterpiece imo. … Right there, is a boat load to unpack historically, politically and psychologically speaking….. I resonate with what you’re saying to some degree. But as I am a man, I cannot speak to a woman’s experience here. Which I think is different. But I will say this, the fire bombing of Germany was unprecedented. Of course Germany bombed London, Moscow and Spain ( testing munitions) mercilessly. Bombed the hell out of them… But it was no where near the quantity of munitions which bomber command/RAF and the allied bombers unleashed on Germany. Obviously Londoners where thirsting for revenge. Make the Germans pay. And many ordinary Germans felt they were deserving ( penance ) of the devastation they received in return. Alls fair in love and war. But scares still live On imo. Putin ( 4 yrs younger than myself) still lives out the fantasy ( deep in his psyche) of revenge even though He was born 15-16 yrs after the fall of Berlin. And my 67 year old native Berliner friend and I still speak of the War every time we talk. Though again we were born on two different continents in the mid 1950s. He buried his 92 year old mother only 2 months ago. She faced down the Russians as they marched into Berlin in 1945. She and He’s teenage father ( a James dean that hated the nazis) never recovered. Not really. The rebellious teenagers, refugees, forced laborers were often the ones to dig the mass graves. And deal with human remains. And WG Sebald and an entire generation of Germans after the War could not let go of the devastation. And the women, children and elderly were often left to pick up the pieces ( psychological bricks, body parts etc) . The positive psychology you mention sounds dreadful. Just like cookie cutter pop psychology that is disseminated by popular culture. Another way to churning a buck. Freud ( most of his clients were affluent women) was nominated for his first noble prize in literature not psychology. He was a hell of a storyteller. Most depth psychologists or humanistic psychologists I’ve known do not not advocate these cookie cutter approaches. Conversely I do believe we do need to become psychologically more literate as a society. But I agree the wholesale prescribing of diagnosis is as dangerous as any extreme right or left wing ideology/ theology.

Report comment

I get the most unusual comments in my email. Makes me wish I hadn’t commented. Dr. Becker seems like a very rational Woman and psychologist. I agree with a number of Her views. Her research and experience seem formidable. I have a cousin that spent much of Her career in women’s public health. She is Harvard graduate and full professor. The discrepancies contradiction undervaluing in women’s care seem clear. I think the don’t talk, trust or feel rule is still widely practiced, but that’s just me…. Also while I understand and respect folks that believe “ god” is an outside superanatural entity with a gray beard, or whatever. I get it. But I feel strongly that the God image is our creation, just like psychiatry. Not the other way around. And the great mysteries psychical, psychologically philosophically still remain as such. I have experienced numinous, holy, wholistic etc. and it is not within the context of rigid fundamental ideologies, religions, psychologies etc. but I respect those that have.

Report comment

So I read Allen Frances 2013 book Saving Normal, in which he admits that the DSM series has created an epidemic of bipolar over-diagnosis.

While Frances says some comforting things, ultimately he rests in my negative column as I read similar tomes. For one thing, he still says old school things like “real psychiatric orders . . . don’t get better by themselves.” While those professionals in my plus column say that naturally things like depression can pass.

But (and I’m sure others have posed a similar question): Why doesn’t the DSM list the criteria for normal?

Despite the title of his book, Frances doesn’t define what he’s trying to save, not like the DSM defines biploar (allegedly not normal). He waxes poetic about normal but gives no criteria, which I find undermines his entire endeavor.

Report comment

That, of course, is the total downfall of psychiatry and the DSM – there IS no valid definition of “normal” on the psychological/spiritual/behavioral level. There is no way to extract “normal functioning” from the society and culture in which such functioning is defined. So their definitions are actually simply a collection of social biases described in some fancy language designed to obscure the fact that they’re basically saying, “Stuff that we don’t want” or “stuff that is hard for society to deal with.” And of course, completely denying that our social system itself is the proximal cause of most of the “stuff we don’t want.” The real challenge is why so many people believe this nonsense that is so easily debunked.

Report comment

Steve says, “The real challenge is why so many people believe this nonsense that is so easily debunked,” –

I agree – this is a huge challenge. But the why isn’t so hard to figure out. I think the reason is because being a psychiatrist means carrying the mantle of medical doctor, which is something most people are conditioned to regard as all-knowing. The “doctors save lives” trope is hard to counter, and the drugs they prescribe are essentially numbing agents (painkillers), and who doesn’t want these in a desperate moment? And since most of the allied professionals (i.e. psychologists, etc) are trained to defer to an m.d.’s assessments, (further spreading the nonsense), it’s no wonder people keep believing the nonsense. It’s been woven into everyday culture. And since most psychiatrists believe it themselves (because they invented it) they are content doing so and are unlikely to say anything different. They see no reason to; they’re happy sitting high on their mountain of nonsense.

One bright spot is that I once heard a psychiatrist say (in response to Mr. Whitaker’s book, “Anatomy of an Epidemic”), is that changes will be from the grassroots, not from psychiatry.

But I didn’t need a psychiatrist to figure that out –

Report comment

“I am not saying there is no such thing as bipolar. When you take a position like this, people always criticize; it is not as extreme as people assume. As a therapist, you have to delve deeply enough to understand the context of what the client is bringing.”

What if there is no such thing as bipolar? The DX has been around for quite a while, and now there are varieties, like bipolar 2, and rapid cycling bipolar (is there a bipolar 3 yet? Maybe the next DSM will give us that). Still:. No blood test. No MRI. Nothing definitive to say that this diagnosis even exists. The fact that people criticize as soon as someone suggests that there’s no such thing as bipolar disorder doesn’t make it any more real. I can say it all day and all night. There is no such thing as bipolar. There is no such thing as borderline. But I have nothing to lose (psychiatry took whatever I had).

Report comment

I agree with those who say that there is no such a thing as “bipolar” or any alleged mental illness. These are all manufactured diseases voted on by psychiatrists at their meetings. Their only benefit is to the psychiatric and Big Pharma community because it is how they base their treatments of disabling psych drugs and therapies. But there is hope and there is a better way of life. It is called leave psychiatry now. Just leave them. You will live. Thank you.

Report comment

Not sure if this is addressed to me, but I left psychiatry years ago. Yes, I’m still alive, but I haven’t recovered anything that I lost. I live in fear every day. Not everyone recovers.

Report comment

People in this society sure have a lot of advice when they see someone in pain. It doesn’t matter how little they know of that person, advice advice advice. That’s why Psychiatry gets its hooks in. Because the idea is that anyone in pain, anyone who is alone, anyone who is suffering is DOING IT WRONG. Well the society is disgusting let’s not forget that.

Report comment

It’s not society. It is us. We are society. We can continue through blaming everyone else for our condition. We have to take some responsibility. There is a time in one’s life when responsibility needs to be taken. Psychiatry does take advantage of those who refuse to take responsibility. Therefore, to be victorious over psychiatry, responsibility. And remember there are those who are more than happy to suffer. we have all had friends and family members who are more likely to tell you their troubles than their joys. The odd thing I have noticed is many times those who have every reason to complain do not. I do not know if that lengthens one’s life, as our lifespan is not completely in our hands, but in God’s hands. But it does make our time on Earth easier and our relationship with others, Ourselves, and God more joyful. Thank you.

Report comment

Right: responsibility. So many lessons and so much advice from complete strangers. More people telling me what I’m doing wrong. So even though I left Psychiatry years ago I haven’t escaped it.

Goodbye to this website and advice from strangers. Not helpful in the least.

Report comment

*happy to suffer. we have all had friends and family members who are more likely”

Rampant assumptions, assuming everyone has family members, has friends.

Report comment

This is pure shaming and victim blaming behavior.

Report comment

Should we tell the diagnosed and medicated preschoolers that they didn’t take responsibility and that is why psychiatry took advantage of them? Tell them, stop complaining?

Report comment

I hope the preschoolers being drugged with Adderall start to take responsibility before it’s too late.

Report comment

She is talking about the misery capitalism brings and how psychiatry medicalises and individualises this misery. She does not say this will continue till the working class, pertucularly working class women get organised and fight back.

Report comment