Editor’s note: The following is a dialogue between psychiatrist Jim Phelps and Robert Whitaker, founder of MIA. Dr. Phelps submitted a blog in response to Whitaker’s essay “Thomas Insel Makes a Case for Abolishing Psychiatry,” which invited a dialogue on whether MIA was doing harm with its critical reporting on psychiatry and the long-term impact of psychiatric drugs. What follows is his submitted essay, a “counterpoint” response by Robert Whitaker, and then a final response from Dr. Phelps. We have disabled the comments in order to encourage other psychiatrists to submit their criticisms of MIA to us, and stir further dialogues such as this one.

The Baby in the Psychiatric Bathwater

by Jim Phelps

Mr. Whitaker, you’re right about psychiatry, on multiple counts. I think you’re wrong on a few. You’re clearly doing good: your book and this MIA website provide important alternative views that are obviously resonating with many people. And… when you paint all of psychiatry as dishonest, corrupted by money, and ignorant of social effects on human experience, I fear you’re doing harm as well.

Let’s start with what you’ve got right. First, no doubt: there’s far too much pharmaceutical company influence on psychiatric practice, from direct payments to academic consultants and speakers, to misleading advertising, and their intimate relationship with the FDA—the latter leading to “approvals” that hinge as much on pharma funding as they do on efficacy in narrowly defined clinical trials.

Second, psychiatry has come to place far too much emphasis on medications and too little on psychotherapy. Therapies are as or more effective than pills for some of the most common problems people face: depression, anxiety, insomnia, traumatic recall, difficulty with eating control, and more—especially if you look at long-term outcomes. Residency training increasingly emphasizes a medical model that tilts learners toward prescribing rather than effective listening, “eye-level” respect (to borrow a phrase from this MIA site), deep inquiry into patients’ histories, and evidence-based therapies.

Third, many in psychiatry do not work hard enough to understand what their patients most want from treatment—e.g. ability to function well and reach their personal goals, not necessarily suppression of voices. Also common is underestimation and inadequate information-in-advance regarding potential side effects (e.g. loss of sexual pleasure; weight gain; loss of energy and motivation); and, as Mr. Whitaker has taken pains to describe, overestimation of medication efficacy. And there are more problems, including the DSM itself, as outlined here at MIA and by the Critical Psychiatry movement.

At the same time, for some people, for some of their symptoms/experiences, psychiatric treatments lead to better outcomes than no treatment. Take mania. Entirely a social construct? The only way you could think so is if you’ve never seen someone who’s fully manic. At its extreme, mania destroys relationships, jobs, finances, and dreams. And yes, for sure: when slightly less extreme, it can provide profound creativity and energy, leading to spectacular accomplishments. And… most of the time, such phases are accompanied by phases of severe depression, when life is monochromal and almost nothing gets done. Obviously the goal of treatment is to prevent the depressions and allow as much freedom of emotion, creativity and energy as possible—without risking a full manic episode.

With effort, that kind of stable mood course can sometimes be achieved with few or no medications. “Social Rhythm Therapy,” for example, includes an intense focus on regular sleep hours that parallel the natural rhythm of the sun. Other non-medication steps are essential ingredients for mood stability for some people, basic “mood hygiene.” (See expert-by-experience Julie Fast’s Taking Charge of Bipolar Disorder and other books.) If these alone are not sufficient, then we can look at adding drugs.

One more example of psychiatric treatment leading to better outcomes than no treatment: the non-manic versions of bipolarity. When bipolar depression is severe, suicide often seems preferable to going on in awful misery. People die. These frightening depressions can be treated by changing one’s sleep hours (so-called “phase advance”), careful use of light therapy, and some forms of omega-3 fatty acids. And… many people have fewer severe episodes with the addition of one or two “mood stabilizers with antidepressant effects,” a class of medications unto itself that includes lamotrigine and several different forms of lithium. For a great example, I’d urge everyone to read a new account so gripping I read most of it standing up on the spot where I opened it: Sara Schley’s Brainstorm. Hers is a great example of how awful bipolar mood swings can be and how fully people can recover.

How long will Ms. Schley’s improvement last? Several decades so far. Could she have achieved this outcome without medications at all, if she hadn’t been given antidepressants for years? That’s an extremely important question. Perhaps so. I spent much of my psychiatric career trying to help people stop antidepressants, and my current research and writing is largely devoted to trying to help people not get started on them in the first place. And… I took fluoxetine myself during my residency. It helped dramatically. But maybe I’m lucky for having been able to stop it after a few months, in the context of therapy and lower stress levels. My point: it’s not black and white, psychiatric drugs are not all good or all bad.

Overall, I appreciate that Mr. Whitaker has raised alarms about the risks of long-term antidepressants and antipsychotics. Psychiatry needs to look again, and again, at these concerns. And meanwhile… I applaud the posting guidelines from this MIA website: our inquiry into benefits and risks should be a “certainty-free zone.” Mr. Whitaker presents one way of looking at things. It’s important for all MIA readers to recognize that there are other perspectives. I’ll close with one example.

Mr. Whitaker may be very right that long-term antipsychotics and antidepressants can cause long-term harm. I fear so. And… look at the studies he cites showing better outcomes among people who did not continue their antipsychotics or antidepressants. Interpreting these results is tricky because of a problem he does not mention: “confounding by indication.” This jargon term means, roughly, “people who do not continue their medications are not the same as those who do.” People who continue are more likely to have severe symptoms, or have had more illness consequences, compared to those who manage to get through without an antipsychotic or antidepressant: not in all cases, just more likely. In other words, people who are more ill are more likely to end up on medications and stay on them. So when outcomes for people on medications are worse, that’s not entirely due to the medications.

Citing this confounding effect, some psychiatrists would say that Mr. Whitaker has got causation all wrong. But that’s the same error: too much certainty. Instead, I’ll just invite everyone to heed the MIA posting guidelines again, this time about the “shame-free zone”: drop the disparaging, blaming, and diminishing of psychiatry. Don’t throw out the baby with the psychiatric bathwater. Mr. Whitaker, I fear you’re doing harm while trying to do good, just as—unfortunately—we psychiatrists are. Let’s together keep wondering, keep asking questions, keep studying: what leads to the best outcomes for which people? We’re all trying to achieve that.

******

Counterpoint

by Robert Whitaker

I want to thank Dr. Phelps for writing his response to my essay on Thomas Insel’s book, Healing. From our inception, Mad in America has sought to stir a societal discussion about the merits of psychiatric care in this country (and abroad), and his response offers an opportunity for a dialogue on this topic.

I will respond here to Dr. Phelps, and he will then have a chance to have the “last word.” We will print whatever he chooses to write without any further reply from me.

Our Mission

Dr. Phelps, in his opening paragraph, writes this: “Mr. Whitaker . . . when you paint all of psychiatry as dishonest, corrupted by money, and ignorant of social effects on human experience, I fear you’re doing harm.”

With that description of me in mind, I think—for the purposes of this dialogue—it is essential that I explain how I came to this subject, and how it informs what Mad in America does. My critique of psychiatry is quite different from that described by Dr. Phelps, and is of a kind that I would think would be appreciated by those who profess a belief in “evidence-based” medicine.

As I have often stated, I got involved in this topic in 1998, when I co-wrote a series for the Boston Globe on abuses of psychiatric patients in research settings. At that time, I was a believer in the narrative of progress that had been told to the public, which was that schizophrenia had been found to be due to a hyperactive dopamine system, and that antipsychotics fixed that imbalance, like insulin for diabetes. That was a story that told of a great medical advance—the molecule that caused madness had been found.

However, while reporting that series, I stumbled upon three studies that belied that conventional narrative.

The WHO had twice conducted studies comparing longer-term outcomes for schizophrenia patients in three developing countries—India, Nigeria, and Columbia—to outcomes in the U.S. and five other developed countries, and each time they found outcomes were markedly superior in the developing countries, so much so that the researchers concluded that living in a developed country was a “strong predictor” you wouldn’t recover if you were diagnosed with schizophrenia.

After the first such finding, the WHO researchers hypothesized that perhaps the reason for the difference in outcomes was that patients in the poor countries were more medication compliant than in the developed countries. They studied medication usage in the second study and found that the opposite was true. In the developing countries, antipsychotics were used acutely, but not chronically. Only 16% of patients were regularly maintained on the drugs, whereas in the U.S. and other developed countries that was the standard of care.

The third study was by researchers at Harvard Medical School. They reported that schizophrenia outcomes had declined since the mid-1970s and were now no better than they had been in the first third of the 20th century.

At the same time, I had interviewed David Oaks and other leaders in the psychiatric survivor community, and they told me of how antipsychotics could damage the brain and how they could compromise their lives in multiple ways, both physical and emotional.

After the series was published, I got a book contract to investigate why outcomes for those diagnosed with schizophrenia were so poor in the United States. There were clearly two contradictory narratives to consider, and as a first step, I called up several psychiatrists and asked if they could point me to the studies where researchers had found that those diagnosed with schizophrenia had hyperactive dopamine systems.

Here is what I was told: researchers had not found that to be true. The statement that antipsychotics were “like insulin for diabetes” was a “metaphor,” one that could help people understand why they needed to take their antipsychotic medication. I have to confess that I was rather taken aback by that explanation.

Those were the seeds for Mad in America, a book that was published in 2002. There was a narrative of progress that had been told by the prescribers of antipsychotics, and a narrative of suffering by those so treated, and I turned to the scientific literature to try to make sense of the conflicting narratives. And what I found was that a close look at the science provided more support for the narrative related by the “mad” as opposed to the prescribers’ narrative. The research told of drugs that could worsen psychotic symptoms, caused horrendous side effects, and frequently inflicted a type of permanent brain injury (tardive dyskinesia).

Fast forward to 2010, when I published Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs, and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America, which investigated the long-term effects of multiple classes of psychiatric drugs. That review told of medications that, in the aggregate, worsened long-term outcomes, with at least a few researchers presenting a biological explanation for why that was so.

Anatomy concluded with an explication of the forces that had driven the American Psychiatric Association to create its disease model when it published DSM-III, and how, following that publication, the APA set out to sell this model to the public. The APA had guild interests pushing it along, and then of course pharma money began flowing to the APA and to “thought leaders” in academic psychiatry to promote this story. With those two forces coming together, a false narrative—of breakthrough medications that fixed chemical imbalances in the brain—took hold in our society.

That was the path that led to the creation of the Mad in America website. I became convinced that our society had organized its thinking and care around a false narrative, and that this was doing great harm to our society, as evidenced by the rising burden of “mental illness” in our society. Mad in America was designed to serve as forum for making the ‘hidden science’ known, and to serve as a forum for blogs and personal stories that could contribute to a societal “rethinking” of our current paradigm of care.

That is the animating force for Mad in America. It is founded on the belief that a false narrative has been told to the public that is causing harm, and that our society needs a new narrative to govern its thinking and care, one that is informed by science.

Psychiatric Drugs

A common criticism of Mad in America (and me personally) is that we are “anti-med,” as though we are motivated by this bias. That is not so, and proof is on display in the solutions chapter of Anatomy of an Epidemic. There, I wrote of a “best-use” model for prescribing antipsychotics that had been adopted by the creators of Open Dialogue in northern Finland to great success.

In that region of Finland, they avoided immediate use of neuroleptics, as they had found that a significant percentage of psychotic patients could gradually get better without such exposure to the drugs and stay well. Those who didn’t begin to improve over the first weeks would then be asked if they would be willing to take a low dose of an antipsychotic, as this might be a path to recovery. After six months or so, these exposed patients would be given a chance to taper from the medication.

With this “selective use” model, at the end of five years, 67% of their patients had never been exposed to an antipsychotic, another 13% had used the drugs for a period of time, and the remaining 20% were taking antipsychotics. Seventy-three percent of their patients at the five-year mark were working or in school, 7% were unemployed, and 20% were on disability.

Those outcomes were markedly superior to outcomes in the U.S. and other developed countries where maintenance therapy was the standard of care. Thus, the solution presented in Anatomy of an Epidemic was not an “anti-med” solution, but rather a “best-use-of meds” solution. The drugs could serve as a useful tool if there was an effort to figure out “for whom” and “for how long” they should be prescribed.

I should note that Dr. Phelps appears to have adopted selective-use prescribing in his own practice. He also writes that his “current research and writing is largely devoted to trying to help people not get started on them in the first place.” That is an effort that I heartily applaud.

However, Dr. Phelps is an outlier in this regard. The narrative that governs the prescribing of these drugs in our society tells of treatments that “work” and hides the dispiriting long-term results, and it is this narrative that precludes the development of such selective-use protocols. I am not anti-med; I am critical of prescribing practices that are not—given the hiding of the long-term outcomes research—”evidence based.”

Diagnosis

Dr. Phelps raised a question about whether I consider “mania” a social construct. People, of course, can experience manic episodes, and Mad in America has published any number of personal stories that have told of such experiences. Mania clearly isn’t a social construct, it’s a description of a mental/emotional state.

However, the diagnosis of bipolar disorder is clearly a construct.

Manic depressive illness used to be a rare diagnosis. This diagnosis was then transformed into “bipolar disorder,” a condition that is much more frequently diagnosed and is often given to people—including adolescents—who are better described as going through a period of moodiness. “Hypomania” entered the diagnostic symptom list, and soon there was bipolar 1 and bipolar 2, and suddenly bipolar was said to be a common disorder.

The changing criteria—and symptom checklists that have been created to make the diagnosis—tell of a social construct. But that is not how bipolar disorder has been pitched to the public. The public has been told that either you have bipolar disorder or you don’t, as though the diagnosis reflects a discrete biological illness.

This is another example of a false narrative doing harm. People so diagnosed now see themselves within this disease framework. Their self-understanding is altered, and the diagnosis foretells a future on drugs and—if the outcomes literature is any guide—of struggles with a chronic condition.

Indeed, outcomes for bipolar today are understood to be worse than they were for those diagnosed in the pre-psychopharmacology era with manic-depressive illness, and the surge of bipolar patients onto government disability is a primary driver of the soaring disability rates that Insel writes about in Healing.

Confounding by Indication

Leaders in American psychiatry have mostly chosen to ignore the long-term studies that tell of drugs that are worsening outcomes, or else, when pressed to consider them, they dismiss the results since they didn’t come from randomized studies. When I or anyone else seeks to publicize these results, we are seen as mistaking correlation for causation. The better outcomes for the unmedicated patients—or so the argument goes—is likely due to their being less ill at baseline than those who stayed on the medication. Dr. Phelps raises this issue in his post.

However, the authors of these reports have, in fact, often investigated whether the results can be dismissed in this way.

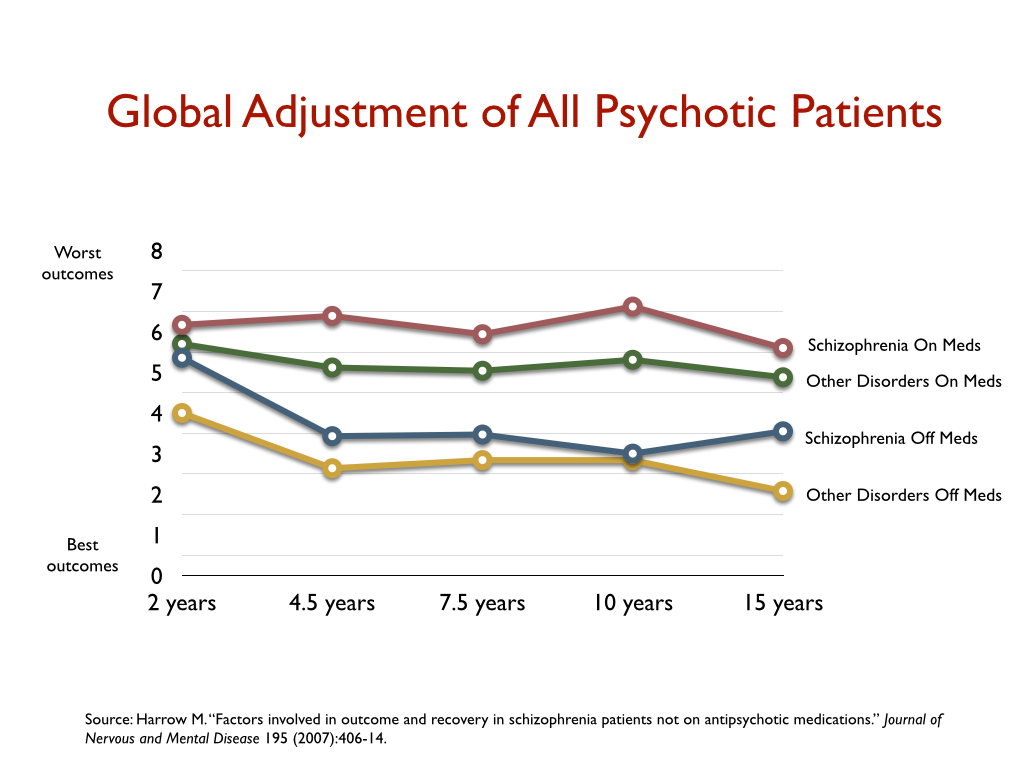

When Harrow and Jobe published their 15-year results in 2007, which told of an eight-fold higher recovery rate for off-med psychotic patients, they did, in fact, offer a “confounding factor explanation” for why the off-medication group had a much higher recovery rate. The schizophrenia patients with a good prognosis were more likely to stop taking their medication than those with a bad prognosis, and it was these good prognosis patients off medication who had the good outcomes, they wrote.

I reported that explanation in Anatomy of an Epidemic. Yet, I had also asked Harrow, in an interview, about data from their report that belied that explanation. Over the long-term, there were four groups in their study: schizophrenia on meds, schizophrenia off meds, milder psychotic disorders on meds, and milder psychotic disorders off meds. I had charted out the outcomes on the global assessment scale used by Harrow and Jobe for the four groups, and that graphic showed that schizophrenia off meds fared better than those with milder psychotic disorders who stayed on antipsychotics.

In other words, those with a worse prognosis at baseline who got off meds did better than those with a much better prognosis at baseline who stayed on the medication. I published this graphic in Anatomy of an Epidemic.

Moreover, in subsequent articles, Harrow and Jobe revisited this “confounding” question, and they reported that in every subset of patients—good-prognosis schizophrenia patients, bad-prognosis schizophrenia patients, and those with a milder diagnosis at baseline—it was those who got off antipsychotic medication that had a better outcome. Finally, in a 2021 paper, they looked at all possible confounders, and concluded that after all such factors were taken into account, the recovery rate for those off antipsychotic medication was six times greater than for those on medication. They wrote:

Regardless of diagnosis, after the second year, the absence of antipsychotics predicted a higher probability of recovery and lower probability of rehospitalization at subsequent follow-ups after adjusting for confounders.

The MTA study of ADHD treatments is similar in kind. The investigators were stunned to find that at the end of year three “stimulant use was a significant marker not of beneficial outcome, but rather of deterioration,” and thus hypothesized that “selection bias” might explain those results. Those who stayed on the drugs through year three may have had worse ADHD symptoms earlier in the trial, they reasoned.

However, when the MTA researchers looked at this possibility, they found the opposite to be true. If anything, the off-med group at the end of year three had more severe symptoms early in the trial. The researchers also divided the patients into five subsets, based on different criteria, to see whether there were groups of youth who were doing better on the medication. Once again, “there was no evidence of the superiority of actual use of medication in any quintile.”

Those are the two longitudinal studies that the NIMH funded to assess the long-term effects of antipsychotics and stimulants. Both studies found worse outcomes for the medicated patients, and confounding by indication did not provide an explanation for the difference in outcomes in either study.

My Questions for Dr. Phelps

In my essay on Thomas Insel and his new book, I wasn’t trying to argue that Insel should draw the same conclusion as I had regarding the long-term effects of psychiatric drugs. I was arguing that in a book designed to investigate why mental health outcomes in the U.S. are so poor, he had an ethical obligation to present and discuss findings from NIMH studies that told of worse outcomes for the medicated patients (or as was the case in the STAR*D trial, to present the poor one-year outcomes for those treated with antidepressants).

Here is my four-part question for Dr. Phelps:

- Should the findings from Harrow and Jobe’s study be publicized to the public and made known within the professional field, including the fact that “confounding by indication” did not provide an explanation for the superior outcomes for the unmedicated patients?

- Should the three-year and six-year results from the MTA study be publicized to the public, including their conclusion that “selection bias” couldn’t explain the poor results for the medicated youth?

- Should the one-year results from the STAR*D trial, which told of a stay-well rate of 3%, be told to the public?

- Is Mad in America doing harm when we publicize these results, and criticize psychiatry’s failure to make them known?

Again, I want to thank Dr. Phelps for writing to Mad in America, and opening up this dialogue.

*****

Response to Mr. Whitaker’s Counterpoint

by Jim Phelps

Before I lose anyone, here’s a summary of the ideas that follow. And don’t forget, I agree with Mr. Whitaker on about 50% of these issues!

- Interpreting the literature regarding the benefits and risks of antipsychotics, antidepressants, and stimulants is not easy. There can be justified differences of opinion among well-meaning people.

- Publishing one’s certainty is fine, it’s your right. But creating and promoting certainty in others’ minds broadens your responsibility. What if you’re steering someone away from something that could help them?

- Lastly, I am so bold as to make a suggestion. Two suggestions, in fact.

Now, to respond to your Counterpoint—and thanks for the opportunity to do so:

If I’m reading you right, Mr. Whitaker, you think important psychiatric research results are not being made public, or made sufficiently clear to the general public. You ask if they should be. And whether doing so does good or harm.

The problem is, as you know, two different people can look at the same study and draw from it different conclusions. Sometimes this is because one person is interpreting the results incorrectly. Sometimes it’s because the two people are starting with different assumptions, or a different perspective based on prior experience.

Or, I regret to acknowledge, sometimes it’s because people just refuse to recognize results that go against their strongly held beliefs—including me sometimes. When this happens, in my experience it’s not usually very productive to dig deeper into the study trying to find the point where the interpretations diverge; or to haul out other studies in support of one side or another. Better is to back up and ask “what are your main concerns here?” Look for the basis of those strong beliefs. That’s what I’d do, were we to sit down over a beer or a cup of tea.

I’m a mood specialist. I hardly ever used antipsychotics and spent much of my time trying to help people get off of them (because antipsychotics are often not necessary for handling non-manic bipolarity). So I’ve not had to dig into interpretations of Harrow and Jobe’s work, for example; or the rest of the literature on antipsychotic efficacy or long-term effects, which I’m sure is quite extensive. But you definitely got me thinking more about antipsychotic long-term effects, beyond dyskinesia risks, with your analysis in Anatomy of an Epidemic.

I’m more familiar with the literature on antidepressant efficacy. As you know, the STAR*D is just one of many studies one should consider when trying to assess: “do antidepressants work, at all? They certainly cause problems. Are they ever justified?” And, crucially, “are these drugs actually making people worse? If so, who? How long does it take? Can these medications be used safely?” Answering these questions requires examining tens of studies, at least. And in the end, most of the answers will be unclear—in my opinion.

Granted, a huge portion of this literature—meta-analyses, randomized trials, uncontrolled studies, case reports, opinion pieces, formal guidelines—is influenced by the pharmaceutical industry. Sometimes the influence is subtle, sometimes it’s remarkably overt. And much of it is due to the very unfortunate relationship between pharma and the FDA. So when reading these articles, one has to keep a big grain of salt in one’s mouth all the time, perhaps a tablespoon or so sometimes.

Your questions for me reflect your certainties. Again, in some cases I agree with you, but I am more uncertain than you are. In the case of antidepressants, I am probably more familiar with the literature on their putative benefits and risks than you are. (Granted, I’m also “in the guild” and could be blinded to some things you can see from outside it.) If despite that familiarity I am uncertain, well, let’s just say I’m concerned about your certainty.

And thus we come to the question of harm. I can imagine a person who’s severely depressed hearing about Mad in America and reading some of the posts here. I can imagine that they would become less inclined than they might have been, before that, to seek help from medical professionals. And yes, I can imagine that for many people, this is a good thing. It would protect them from getting an antidepressant when their own social supports might rally and pull them out of that depression—more safely, with no long-term risks (indeed, only more benefits!). And… I can also imagine a severely depressed person hearing the MIA perspective on psychiatry and never discovering that their recurrent depressions were related to their phases of subtly increased energy and that by controlling their sleep hours, they could prevent some of those depressions.

I can imagine someone with clear manic shifts, whose spouse is desperate because his repeated episodes of spending are sinking them financially. Say that person has a friend who has read your book, who says “oh, psychiatrists, they’re just pushing pills that can make you worse; don’t listen to your wife. You’ll figure this out.” You get the point: I believe there are risks in promoting negative views of psychiatry.

Perhaps the benefits of your book and your MIA efforts outweigh these risks. But what if you could help nearly as many people and lower the risk for the rest? What if being less overtly negative in your language about psychiatry and psychiatrists; more frequently acknowledging that there are some psychiatrists who are not like the rest; and perhaps even helping people identify, via MIA, ways to identify preferred psychiatrists in case that level of care is needed—mightn’t that improve your “benefit/risk ratio”? (Thank you for unlumping me, by the way. There may be many more psychiatrists like me than you think.)

Care for a beer or a cup of tea sometime? After an offline version to ensure we’re both okay with it, perhaps we could even take our drinks online, on MIA, as we carry on this discussion.

Nice exchange. Firstly, I whole heartedly agree that people suffer, and they do so egregiously sometimes. People become depressed, manic, anxious, panicky, have distressing intrusive thoughts, believe things which aren’t true, see and hear things which aren’t there etc. and in the throes of suffering they want help. Other times, someone forces them into it. I simply disagree on how they handle it, what they tell to people who come to them, and that individuals have very little idea of what they’re getting themselves into, medically, socially and legally.

1.) There is talk of mania. But what about antidepressant induced mania? That SSRIs cause manic episodes in people with no prior history of them, and they are subsequently relabelled “bipolar”, a term which can have serious connotations socially and legally?

2.) What is Mr. Phelps’ opinion on “Personality Disorders”? The recently famous Johnny Depp vs Amber Heard case made use of the notion of these nonsensical disorders as well, where one psychologist “diagnosed” Heard with “Borderline and Histrionic Personality Disorders” whereas the case could simply have proceeded based on the actions and behaviours of them both, and mitigating factors involved (which can include mental health in terms of the actual state of mind of the person, i.e. depressed, anxious etc.) without these junk diagnoses having any place in them. You can easily say “she is lying”, “she has shown a consistent pattern of lying” etc. That’s enough. They then brought in another psychologist to rebut the psychologist who “diagnosed” Heard.

In the interests of not getting my reputation destroyed, please note that I have NEVER been labelled with this psychiatric ‘diagnosis’/label/categorisation. This post is merely to explain what psychiatric categorisations, irrespective of what they are, are like.

i.) For example, if a person is moody or volatile, or has strong opinions or whatever it is, it can be stated as is without being re-wrapped in those circular labels which are then used as if they have agency. A dangerous slight of hand trick which permanently damages a human being, casting aspersions on the very essence of their being for life. Easy-to-use to gaslight and invalidate a person. You could simply state, “He has shows a consistent low mood” along with supplanting evidence, “she has shown a consistent pattern of lying”- with supplanting evidence. The accused can present his/her reasons for their behaviour. Why are mental health workers able to use these terms in court as explanations?

ii.) Why are psychiatric students still spouting “there is nothing derogatory about psychiatric labels, it’s just like cancer or diabetes”, when cancer and diabetes have nothing to do with a person’s character, conduct, sanity or reputation and all psychiatric categorisations cast light on those things?

A simple search on social media shows how these terms are used:

a.) What is the most effective way to deal with a slander campaign from a Borderline Personality Disorder ex?

b.) Have you ever been widely slandered by a person with Borderline Personality Disorder? How did you handle it?

c.) Is is best to cut someone who has BPD out of your life?

d.) https://www.quora.com/Why-are-people-with-BPD-so-hated?share=1

In the 4th link, Nav Ng who says he’s been abused by a ‘BPD woman’ writes pretty clearly:

“BPD people:

For God’s sake don’t start any relationships without warning potential partners of your condition. Kindly don’t inflict your misery on the rest of us.

And don’t ever bring a child into this world, it is worse enough already with the rest of us suffering from your lot being let loose in society. Consider sterilising yourself, if you have any empathy left.”

Each of these people write about their experiences with certain abusive and difficult people. But note that none of them simply say that: that they have had abusive people in their life. They shoehorn the term ‘Borderline Personality Disorder’, a defamatory and tautological psychiatric categorisation into the picture. And individuals in mental health have the audacity to say that these categorisations are ‘just like diabetes and cancer’.

People should always get justice from unwarrantedly abusive people. But not on the basis of psychiatric categorisations. Rather it should be based on actions and mitigating circumstances.

This is clearly a function that psychiatry provides. To do away with unwanted individuals, not simply in terms of their actions or behaviour, but rather on the basis of the psychiatric categorisations applied to them. It always provides a useful function to label the opposite party with some kind of a ‘disorder’ for this purpose. In those same links I provided, you’ll find people put under the BPD categorisation argue with others trying to disprove their position about those “with BPD”.

For all the abusive individuals placed under these categories, think of how many people whose lives have been ruined by abusive individuals got placed in these categories. Think of how many already hurt people psychiatrists and psychologists have (even inadvertently) re-hurt and marginalised from society by psychiatrically labelling them, only for those people to be gaslighted into oblivion and anonymity.

It is perfectly legitimate for people to ask to be not labelled with ANYTHING in the DSM. It’s a legitimate defensive response.

Report comment

Extremely well said, Registered!

Report comment

Comments are closed.