I tried to kill myself when I was 14. It wasn’t the first time. My psychiatrist had just upped my Prozac, a whole lot of unresolved early childhood trauma had flared up at puberty, and the baseline sadness and confusion I felt mushroomed into an overwhelming desire to die. The thoughts wouldn’t leave me alone: Everything I could think of circled back only to suicide. I wrote out a suicide note and made an attempt.

I won’t go into the horrors of waking up alive in an emergency room where the staff was clearly annoyed they had to deal with me and my “attention seeking” behavior. (I have written about this elsewhere.) I won’t go into the indignity of being involuntarily locked up, time after time, until I satisfactorily convinced the staff that I wouldn’t harm myself or attempt suicide again. (I was lying.) The system taught me to lie, to hide my suicidal feelings in order to escape yet another round of dehumanizing lock-ups and “treatments.” Rarely did I feel seen or heard in the various settings I was committed to over the years. Generally, I felt more like an object to be diagnosed, dosed, and kept alive against my will.

My champions generally came from outside the mental health system. Mr. Harris (no relation), my high school Honors Comp teacher, came to visit me in the psych ward after an attempt. I was embarrassed to let him see me like that, but I was also secretly happy he showed up. He didn’t see me through the lens of diagnosis or deficit or as a “suicidal patient.” He saw me as a gifted writer, and encouraged me to keep writing. Mr. Harris literally shined the very first light that helped me to journey out of suicide and back to life. (Believe that you, one human being, can make that much of a difference in someone’s life. He did, with no special “training” or “expertise.”)

When I was 25 years old, I made the decision to be “out” as a person with a psychiatric history and past suicide attempts, and entered the world of mental health activism/advocacy. My first real job in the field was in 2008 with a small suicide prevention non-profit. I was hired specifically for my lived experience; but everywhere I went, the only voices that seemed to matter were those of the MDs, the PhDs, or the “suicide survivors,” family members who had lost loved ones to suicide. While these voices are certainly important and we owe much to the grassroots suicide survivor movement for raising awareness about suicide, I wondered why there didn’t seem to be any interest in hearing the perspectives of people like me, who had survived suicide attempts.

I resigned from my suicide prevention gig after eight months, not because I believed people’s hearts were not in the right place but because I instinctively felt the prevailing approach was inadvertently making the problem worse. I also couldn’t continue to do grants stewardship for one of their funders, Eli Lilly, whose drugs had caused myself and others to be more suicidal.

I was troubled by the master narrative of suicide prevention, which is all about “promoting help-seeking behaviors,” ostensibly for some underlying, untreated mental health condition. Okay, so let’s say someone heeds the suicide prevention call and gets into treatment. What kind of help will they receive? Likely, a diagnosis, some pills that they may or may not be told they need to take for life, and a discharge. Furthermore, at least one study indicates that “the risk of suicide is higher during the period immediately following discharge from inpatient psychiatric care than at any other time in a service user’s life.” I would argue that this is not only due to lack of follow-up upon discharge, as the study asserts; it is also because most mental health care systems and providers don’t know much about promoting hope and well-being after a suicide attempt. Suicidology experts concede that the training most mental health professionals receive regarding suicide is “woefully inadequate.”

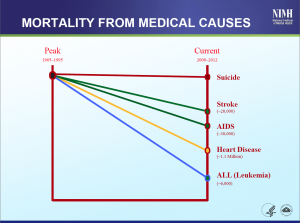

What I have noticed about suicide prevention is that despite all the brains, money, and good intentions being poured into it, it doesn’t seem to be working. I recently attended a research progress meeting at the National Institute of Mental Health, where NIMH director Dr. Thomas Insel shared some very disturbing trends. He showed a chart comparing mortality from stroke, heart disease, AIDS, and leukemia from 1990 to 2010. In every single case, there have been noticeable, impressive decreases in mortality over this time period. Most striking is that AIDS, which was once an almost-certain death sentence, is now seen as a “Chronic Manageable Disease.” The decrease in mortality stops when we come to rates of suicide, which remain largely unchanged over the very same time period. Why isn’t the suicide rate going down?

Here in the United States we spend more per capita but have overall poorer health outcomes compared to other similarly wealthy nations. As Robert Whitaker argued in Anatomy of an Epidemic, more and more people are being permanently disabled by mental health conditions – at an alarming rate. Mental health/substance use issues (especially depression, anxiety, and other conditions) are among the leading contributors to chronic disability in the United States, according to a 2013 JAMA study. Consider the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010, which is the largest study of its kind looking at mental health and substance use worldwide from 1990 to 2010. Since 1990, the “global burden of disease” attributable to mental health conditions and substance use, as measured by the number of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs), rose 36 percent worldwide. The studies’ authors attribute this rising “global burden” to age and population growth. Now, I’m no public health expert, but these results do beg the question: Why aren’t people getting better when it comes to mental health-related conditions? Robert Whitaker has much to say about this, including the dominance of the medical model approach and the indiscriminate and often irresponsible over-prescribing of psychiatric drugs. Remember that people diagnosed with severe mental health issues die, on average, 25 years younger than the general population.

These statistics suggest something is fundamentally wrong when it comes to our national and global approach to suicide. What has been missing from the suicide prevention puzzle? The voices of people who have intimately known what it feels like to want to die. Even today, if you took a straw poll of suicidologists to see if there is value in our voices and perspectives, I believe that few would see it. Ironically, this perspective is at odds with the views of Dr. Edwin Shneidman, largely considered to be the founder of suicidology, who viewed the perspectives of people with lived experience of suicide as critically important. He wrote in The Suicidal Mind (1996): “the keys to understanding suicide are made of plain language…the ordinary everyday words that are found in the verbatim reports of beleaguered suicidal minds.” You would never know this to attend today’s suicidology meetings, which are much more concerned with studying statistics about people who have completed suicide, rather than talking to those of us who are still alive. David Webb, author of Thinking about Suicide, defines suicidology’s current prejudices against the first-person voice of survivors as “scientism,” or the belief that only the third-person, or scientific/medical, narrative is what matters. It is this very scientism that persons with lived experience of suicide must challenge head-on.

I myself was at first very reluctant to engage with a field that didn’t seem to value my perspective, as it caused me to re-experience traumatic memories of being silenced and suppressed by mental health professionals in the past. But the good news is that the dominance of scientism in the suicide prevention world is slowly eroding. For years, people like Eduardo Vega, Heidi Bryan, Mark Davis and DeQuincy Lezine have been lone voices trying to get the entire suicide prevention field to see the importance of the attempt survivor perspective. In large part due to their hard work, and allies and champions within the American Association of Suicidology, it looks like a new Suicide Attempt Survivor Division of AAS is on the verge of becoming a reality. My hope is that the voices of suicide attempt survivors will not only be taken seriously within AAS, but that their “lived expertise” will come to drive all research, policy, health care priorities and community responses to suicide.

In the last few years, there are a growing number of suicide attempt survivors who are willing to speak out and challenge the status quo. Live Through This, created by Dese’Rae Stage, features the images and stories of people who have attempted suicide. The American Association of Suicidology has launched a blog, run by journalist Cara Anna, which features over 60 distinct voices of people with lived experience of attempting suicide. I don’t agree with every perspective I read on that website, but it is exciting to me that so many people are now willing to publicly break down the taboos around being “out” as a person who has struggled with suicidal feelings and attempts. Like the HIV/AIDS movement in the 1980s and 1990s we are a highly stigmatized group; but I also believe that, like the HIV/AIDS movement, we have the power to change attitudes and demand change with our advocacy voices.

A heartening development for me was a recent historic summit sponsored by the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, which sought to bring together its Suicide Attempt Survivors Task Force, as well as members from its Clinical Care and Intervention Task Force, launching a new Zero Suicide initiative. (Click here and here for some reports on the event, from an attempt survivor and clinician perspective, respectively.) For the first time, I was able to sit in a room with clinicians and feel that my voice was not only heard but valued and respected. I was able to say things that I didn’t feel safe saying if I wanted to keep my suicide prevention job in 1998. I was able to say that “safety” in the context of my treatment was always a euphemism for coercion, and that well-intentioned efforts to keep me “safe” caused only more harm and trauma. Cara Anna said that “treatment should never feel like punishment” and I emphasized that “forced treatment has no place when it comes to mental health or suicide.” Melodee Jarvis talked about “celebrating our stories of survival.” Tom Kelly said, “I’m a person. I’m not a lost cause.” These are sentiments and concerns that have heretofore not been uttered in mainstream suicide prevention meetings. We have a long way to go to see a grassroots movement of suicide attempt survivors that will be able to influence the way suicide is understood and responded to on a national and global scale, but this dialogue was an encouraging beginning.

What Can You Do?

Tell Your Story. If you are a suicide attempt survivor, or someone who lives with suicidal feelings, I encourage you to “come out–” if and only if you feel ready. Find someone you can trust; write a blog post; create a video; send a selfie to #todayistandup on Instagram; do whatever you can to break down the scary walls of silence and shame around this issue. Share what system and social responses hurt you and added to your suicidal burden; tell us what gives you hope; and explain how you cope and stay alive in an often-hostile world. Tell us about the relationships that helped bring you back to life. We need your wisdom and your vision. The more of us who speak out, the more power we will have to end discrimination and effect the radical changes we want to see in how suicidal people are treated. Our voices are needed everywhere to shift the perspective from a narrow medical model, deficit-based approach, to a holistic, strengths-based, community-wide suicide response.

Join [email protected], the international Suicide Attempt Survivor discussion list. I started this list several months ago to promote respectful dialogue among suicide attempt survivors, to get politically organized, and to share resources and information. Lots of great ideas are being generated there, such as the need for an independent advocacy network of people with lived experience of suicide (which is coming soon!) as well the need for a national survivor-run 24/7 chat/text service to support people experiencing thoughts of suicide. We need your energy and support to bring these and other hopeful ideas to fruition.

Join the #SPSM (suicide prevention social media) chats on Twitter. I have participated in a few of these, and it’s a great way to influence the conversations and bring a lived experience perspective. People on Twitter constantly bemoan the lack of survivor and advocate voices in these conversations, so please get on Twitter for some respectful dialogue and to share your ideas. Find me tweeting about suicide and well-being @leahida, and follow @beyondmeds, @aboutsuicide, @unsuicide, and @lttphoto for a start.

Learn how to be an ally/practice Emotional CPR. I recently had the pleasure of co-presenting (with Will Hall) a workshop on a public education campaign we are developing called “Emotional CPR for People with Suicidal Feelings” at the Tools for Change conference in San Francisco (#tfc2014). In the workshop, we talked about why current, fear-based responses to suicide only drive the problem, and how we can all practice responding from a place of hope and belief that healing is possible. People told us that they appreciated eCPR’s use of role plays, which we used to contrast the typical fear-and-liability-based response with examples of open-hearted, curious responses that honor the person’s profound pain with respect and dignity. To be an ally to someone who is suicidal means that we practice listening without judgment; that we validate the person’s experience; and that we work collaboratively, not coercively, to help the person find the right supports they need to cope with their suicidal thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Make a commitment to be a part of the solution. For too long, we have been told that community members must leave it up to the professionals to deal with suicide. As a result, we as a society are “illiterate” when it comes to suicide. Not only do we not know the signs, we generally have no idea how to respond in a way that’s actually helpful. But we can and should each be prepared to play an important role in supporting someone through a suicidal crisis. If we truly want to make change, we can’t leave it solely up to the police or the clinicians (who, as we saw earlier, mostly do not have training on how to respond to suicide). We must learn to honor the suicidal experience as a deeply human problem, a universal problem, a “crisis of the self,” as David Webb so eloquently puts it, and to do much better than a severely limited medical model that locates suicide in faulty biology or genes. Understanding suicide as a medical issue/biological disorder only breeds the current state of fear, misunderstanding and discrimination. Understanding suicide as a human struggle is naturally de-stigmatizing and generates authentic compassion.

Create Safe Community Spaces. For too long we have been told that we cannot speak openly about suicide, that we will somehow spread it via “contagion.” That advice demonstrates complete ignorance. We must create truly safe spaces everywhere, where people can speak honestly about suicide without fear of coercive interventions. We can all be a Mr. Harris and go beyond the approach of simply preventing someone from dying by any means possible (even if it kills them), and instead practice supporting them, in a spirit of respect and collaboration, to find reasons to live. Forget just “preventing” suicide. Together, let’s create real community alternatives!

I believe that by returning to the humanistic roots of suicidology, elevating the first-person experience to its former centrality, and creating safe, culturally respectful spaces to unload our suicidal burdens, we just may have a chance of reversing our global epidemic of suicide and distress.

* * * * *

Thank you for suggestions about things that we all can do to help one another so that suicide doesn’t have to become the option that frees us from overwhelming distress and misery. This is much more proactive than anything the “mental health system” ever does for people. All they want to do is drug us to the gills and numb us to our issues and distress while never once helping us with anything practical that might enrich our lives to the point that we would rather live than die.

I was held in a private hospital before I was sent to the state hospital. A number of us were there due to issues of suicide. A number of us would gather every afternoon and talk about our “stuff” and in essence we did group therapy for one another. The staff of the “hospital” told us to not talk about “suicidal stuff” and became angry with us when we continued to do so. Those afternoon gatherings were the beginning of my finding balance for my life once more. That private hospital charged people $1,000 per day and we had to do our own therapy about our own suicidal issues! Of course, they were all too happy to try to drug us to the gills and make us numb.

Report comment

Stephen – “All they want to do is drug us to the gills and numb us to our issues and distress while never once helping us with anything practical that might enrich our lives to the point that we would rather live than die.” Wow, that is so, so well put. What a powerful story, these are exactly the kinds of stories we need to be hearing, sharing, and corroborating. I am so sorry you went through that hell. Thanks for speaking out.

Report comment

I also made the staff, and still make the staff, of the state hospital where I was held and where I now work, very uncomfortable and upset when I claimed and still claim that I was not “mentally ill” because I tried to kill myself. I did not have a “chemical imbalance’ that caused me to want to take my own life. Suffering and grieving overwhelming losses experienced over a short period of time was the problem, not any “chemical imbalance.” But no one wanted to hear about or help me deal with those losses, other than fellow “patients” and a few student nurses here and there in my hospitalization.

In fact, I’ve been told by some staff where I work that I shouldn’t say that I wasn’t mentally ill.

Report comment

That is also common practice. In the psych ward they kept me in I tried to talk to another person in the evening and the staff immediately appeared (otherwise they never had 5 minutes time for you) and told us to go to our rooms and stop disturbing the peace. Psychiatric hospitals are dehumanizing and not better than prisons.

Report comment

Leah, I always get a little worried when I read an article about suicide prevention, because I used to supervise at a volunteer suicide hotline and watched the changes over time as we got farther and farther away from a trauma-based, human-interaction focused model to the dominant medical model we see today. Most of the writing, including from the AAS, are about knowing the signs and getting “treatment.” And you are right, there are almost no voices from survivors of suicide attempts, or of the ham-handed interventions that are supposed to help.

I was so impressed by what you had to say, as it completely reflects my own experience as a counselor and a person who has at times struggled with suicidal feelings. Your emphasis on being present for the person and not judging him/her for having his/her feelings, which in my experience are almost always very understandable given their experiences, is exactly what the mental health world as a whole needs to hear. I am so glad you’ve found your voice and helped others find theirs. I really do believe this is the only way the mental health world will reform – when those who have to suffer through its “helpful” interventions stand up and say NO MORE!

Thanks for a moving and inspiring article!

— Steve

Report comment

Steve, thank you so very much for your comments. “I really do believe this is the only way the mental health world will reform – when those who have to suffer through its “helpful” interventions stand up and say NO MORE!” Yes! This is right on. I am excited about parallel efforts where folks are setting up their own support networks independent of systems, like the Hearing Voices Networks and attempt survivor support groups. We gotta take it back to the grassroots and out of institutional or quasi-institutional settings! Thank you for the work you do in the world.

Report comment

Mental health emergency helpline – “we don’t have time to talk to you, go to the hospital”. I’m not even kidding.

I disagree that the current system is so despite people’s best intentions. some of the people working in the system at best don’t give a flying f***, at worst enjoy exercising power over vulnerable others. the only human reactions I received were 100% from people outside the system. Psychiatrists, psychologists and most nurses (except one who ended in a psych ward because he couldn’t get a better job) were all abusive and some of them psychopathic.

Report comment

Leah, thank you so much for telling your story, which echoes the experiences of so many of us who have been shamed, blamed, and forced to accept “treatment” that didn’t meet our needs because we wanted to die. One would hope that the so-called “helping” professions would react with compassion to people who are in such despair that the only escape they can see is to end their lives. And the public seems to have absorbed these ideas – people say things like how selfish people are who complete suicide, or how “unfathomable” it is that someone would want to die. Those of us who have been there understand and our insights would be valuable to the field if they would only listen. I’m so glad you are out there saying this to people who need to hear it!

Report comment

Thank you, Darby! I hope to start some real, honest dialogues about how we can really respond to and address suicide in a useful, strengths-based, trauma-aware way–not just prevent it. Sadly, we have to work with a system so deeply mired in fear and liability/risk concerns that honest conversations are rarely possible. If they happen, they often happen by accident, or because a counselor or professional was ignoring the rules. And then there are all the ways society fears, sensationalizes, shames, and demonizes suicidal people. So there is a lot of fear, ignorance, and static to overcome, but I see things changing.

Report comment

I have experience on crisis hotlines, where we are required to follow a very specific protocol if someone even MENTIONS suicide. Again, this can be in a very often-hand way and not something they are serious about. We are still required to ask them very specific questions about their suicidal ideation (even if it is almost non-existent). In many cases, this means de-railing the conversation a caller would actually LIKE to be having–which is often regarding the issue that puts suicide in their mind in the first place.

In the mental health professions, protecting your own ass is always of utmost importance. It may not even be something you want to do, but if you work for an organization or agency, this may be a mandatory part of your job.

For social workers, this mandatory repeating means saying things (as a social work teacher did in class): “Don’t share anything about [your own] childhood abuse if you don’t want me to report it.” Is it just me, or is this model a really odd way to conduct human relationships?

Report comment

My first question when I had a suicidal caller, once I figured out if they were on the verge of doing something drastic, was to ask what was going on in their lives that made suicide seem like an option they would consider. It always led to a very productive conversation. It is a shame they wouldn’t do what made sense to you as one human to another.

—- Steve

Report comment

Yes, when we get into assessment mode, we destroy the relationship and trust that is so essential to someone healing and finding their way back to life.

I don’t care how “sensitive” the instrument is — when someone is in assessment mode, they immediately have an agenda other than just to listen to or be with the person in distress. The funny thing is, I find when you give someone the space to explore without fear of judgment or coercion, they themselves usually naturally go to what is driving the suicidal feelings. As you say, this is something you miss completely when you start to focus on the frequency of suicidal feelings, the duration, etc.

Fear/risk/liability concerns, in my opinion, really do interfere with the formation of genuine, respectful, mutual human relationships – ironically, the very thing that many of us have found to be very healing as we struggled to cope with suicidal despair.

Report comment

The continuing tragedy is how little is done for those who reach out when suicide is being considered. Locally, this often means police outreach, hours to days sitting in the ER, and some time in the cold comfort of a locked psychiatric unit. (My county’s mental health system review committee doesn’t even track ER boarding of less then five days.)

I fear co-morbidities and premature mortality among mental health consumers is of little concern to society at large and “attrition” has never been cause for action in the mental health system. It is telling that The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Suicide (1999) and the National Strategy to Prevent Suicide (2000) were followed a decade later by a higher suicide rate. Words alone are never enough but they are often all that is provided.

Report comment

Joe you paint a very sad but true picture. The lack of success in addressing the suicide rate is evidence, to me, of a flawed approach. We do need to go beyond words to question the fundamental assumption: is a medical/disease approach to suicide the right one?

Report comment

“The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Suicide (1999) and the National Strategy to Prevent Suicide (2000) were followed a decade later by a higher suicide rate”

Totally predictable. All they had to do is ask surviviours beforehand. The only time I tired to kill myself for real was in the “hospital” and because of what they did to me. People who work in locked wards are criminals.

Report comment

Just wanted to say that many of us who are survivors of suicide loss are also survivors of our own suicide attempts. After my son died as a result of prozac induced suicide, I made three medically serious suicide attempts. It would be a shame to suggest that those of us who watched our children tortured and killed by psychiatry and in the aftermath were forcibly detained and medicated and attempted suicide do not have a ‘survivor’ perspective to offer. We have had to fight very hard to be heard. In my country it is perfectly legal to speak out about attempted suicide but an offense to talk about the medication induced completed suicides of our children.

Report comment

Maria, I am so sorry for your loss, and the devastation you have experienced. And I am so sorry if my writing at all implied that we aren’t in this together. Your perspective is certainly valid and hugely important, and I know how awful it feels not to feel heard. I only wished to make the point that the loss survivor voice had been more included here in the US. It’s sad and scary that we cannot have an honest narrative about drugs and suicide. I was part of a group of people who worked very hard to get the black box warning put SSRIs for youth. Though they clearly have the same effect on some adults as well.

Report comment

I wish there wasn’t so much vitriol against medication. I think it’s misguided. Not everyone needs it, and everyone has been on the wrong medication at some point and has suffered. For others- it’s a life saver. So stop acting like its the worst thing and make people feel bad about having to take meds. I wish I could be off them but it’s not in my cards.

Report comment

I am sorry you are getting that vibe – it is understandable, as some folks express some very strong feelings about their bad experiences on medication, but I don’t think most of the folks here oppose medication as one option in the toolbox. I think it is the enforcement of the viewpoint that medication is the ONLY thing that will help, and that biology is the ONLY explanation for your suffering, that leads to the vitriol. In the end, people are objecting to being harmed by the rigidity of the system, as well as by the intellectual dishonesty and downright greed of those perpetuating these misguided fake-science dogma. And medication is often the means by which this harm is inflicted.

Try to imagine if you had become MORE suicidal after starting on some recommended medication. Then imagine how it would feel if you told someone this was the case and they didn’t believe you. Then imagine how it would feel if you decided to stop taking the offending medication, and they locked you in the hospital and forced you to take it. Or imagine if they did this to your child and s/he committed suicide as a result of the side effects, and nobody listened to you when you said something was wrong. You’d probably express some vitriol, too.

If you look at Leah’s suggestions for improvement, no where in there does she say not to take medication or to stay away from doctors. She is talking about speaking up, about listening to those who have been suicidal, about connecting up with others who have had similar experiences. I am sure if you did so, you’d find that some people swear by their medications and say they could not do without them, while others want to sue their psychiatrists and the drug companies for ruining their lives. Both positions are very real and very welcome. I think you get more medication horror stories on this site because it’s one place a person can go to speak from the heart about their experience and not feel invalidated. I don’t think it’s meant to invalidate your experience if it has been different. My personal view is very pragmatic: we should work individually with each person and find out what works for him/her. It is only when we decide that there is a “right way” to “treat” suicidal people that we get into big trouble, especially when we don’t even bother to ask the suicidal people what they think about our supposedly helpful interventions.

—- Steve

Report comment

Thanks Steve.

I have had those experiences. As a matter of fact I was hospitalized a few weeks ago after a thwarted attempt (someone found my gun– i don’t mess around), and my time there felt like prison (ms. harris is quite right about feeling punished). I had no agency over my medications and felt like an animal. Perhaps what I should really be saying is – that articles that address the negative affects of drugs and the poor treatment people ( like myself receive,) should ALSO say CLEARLY that they aren’t advocating for people stop taking medications carte blanche.

Report comment

Ugh! It does not sound to me like whatever treatment you are receiving has been very effective! Let me know if there is any way I can help.

There are a lot of “off the grid” approaches that can provide some relief to some people. Honestly, my biggest problem with the system is situations just like yours, where they appear to be applying the best technology and know-how that their particular world-view has to offer, and it isn’t taking care of the problem. They have literally nothing else to offer you! It makes me both sad and very angry. I wish you were in Portland and we could meet for coffee and look at options. It’s all about maximum options and getting to know each person’s story. That’s what’s missing in the current approach. It’s not the drugs, it is the lack of caring and the lack of creative flexibility that pisses me off!

— Steve

Report comment

Walnuts, I love Steve’s answer and yes, this post was certainly not intended to make anyone who takes medication feel bad. I would never presume to judge anyone for their choices and I know many people have been helped by medication.

I just wish myself and my family had been warned of this potential adverse effect, so we could have been aware. It would have saved us all a lot of pain and suffering.

I hope you won’t spend one moment feeling shame or bad for whatever you need to do to take care of yourself.

Report comment

Oh Leah. THANK YOU.

Report comment

“make people feel bad about having to take meds.”

Like that’s a problem. The real problem is taht people are coerced and often forced to take drugs that make them physically sick, mentally destroyed and often lead to suicide or death from medical reasons.

I’ve heard the story of “my drugs saved me”. In the same time there are people who believe homeopathy saved them or prayer saved them or drinking their own urine saved them (yeah, the last one is a thing). It’s all good and fine and you’re entitled to your believes but if we really care about “evidence-based medicine” which we’re supposed to care apparently then psychiatric drugs have almost no efficacy. Worse than that, anti-depressants can cause suicide.

So if you want to take you meds please continue to do so, it’s your life and your body but don’t complain when we’re trying to inform people. Informed consent should be the right of every patient and it’s clearly not the case right now.

Report comment

Thank you for the courage to speak out and your advocacy. Your an inspiration to us all.

Report comment

(Please be a forgiving for my English ;))

I don’t know where I can come out with my suicide feelings. So I think that good solution is to do it here. I’m from Poland, I’m 22 years old. In my life I only took a 2 pills of Hydroxyzine, so practically I have nothing to do with psych drugs. I just hooked up with Polish psychiatric and psychological help. I rarely drink alcohol – I would never do it. I do not smoke anything. I do not take drugs. My only destructive way of dealing with mental pain is frequent, nonsensical use of the Internet.

I have suicidal thoughts every day. Today my first suicidal thought was 30 minutes after waking up – I realized that I would spend another senseless day and I wanted to die for that.

It isn’t a really desire of death. On the axis Life (100%) — Death (100%) I was pushed by people to death side and I can’t get out of it. In my case it’s easier to look in the direction of death.

In short what is going on with me. I’m tired. I feel like someone got me out in the washing machine. Sometimes when I woke up in the night I was afraid that I would not have the strength to get out of bed (anxiety is good – it stimulates action). I am lonely – I live in emotional isolation. Practically I have no friends. I never had a girlfriend. I am aware of my abilities, which I can not use – I was great at learning science at school. From October I start again studying…

I had some spiritual experience, so I know I do must to live with this emotion always. I had short moments in my life where I did not need anything and was fulfilled! I was in this state to which people strive. I have experience to refer to. Although they are so distant…

I hope the body directs me through thoughts in a good place.

I do not want to live unconsciously – that is why I do not want to take any pills. And I do not want to live in even greater humiliation… If the situation forces me to living in humilitation, I’ll say goodbye to this world.

Report comment

Leah this is a very important post. My very first article I ever published in MIA I first pitched to a suicide survivors site. Sadly that site got taken over by the voices of “professionals” so they sure did not want my article. MIA did!

I am going to be recommending this article in my radio show today, August 19, 2017. Tune in at noon. 323-443-7210 blog talk radio juliemadblogger show.

Report comment