This week a commentary, written by members of the University of Pennsylvania Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy and titled “Improving Long-term Psychiatric Care: Bring Back the Asylum,” was published in JAMA Online. The senior author, Ezekiel Emanuel is former Special Advisor for Health Policy in the Obama administration and brother of Rahm, Mayor of Chicago and Obama’s former Chief of Staff. This commentary with its provocative title published in a high impact journal by a well connected physician is sure to garner considerable attention and influence.

As the title suggests, the authors recommend a return to asylum care, albeit not as a replacement for but as an addition to improved community services and only for those who have “severe and treatment-resistant psychotic disorders, who are too unstable or unsafe for community based treatment.”

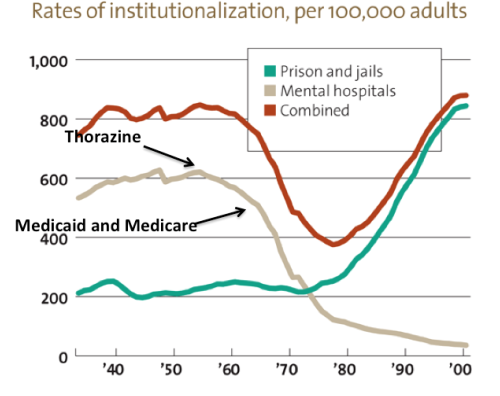

The authors seem to accept the notion of transinstitutionalization (TI) which suggests that people who in another generation would have lived in state hospitals are now incarcerated in jails and prisons. This notion arose from two sets of statistics. The first is that as rates of psychiatric hospitalization declined rates of incarceration increased with the total in 2000 being about the same as it was in 1960. It gives the appearance that we just transferred people from one setting to another.

The other statistic referenced is the high rate of mental illness among those who are incarcerated. The JAMA authors conclude that we can not escape a certain level of institutional care. They are ethicists who argue that it is more humane to place those with mental illness in psychiatric hospitals than jails. Hence the call for asylums.

I have never been comfortable with this hypothesis because it did not comport with my experience. Although I knew that many in our state prisons were prescribed psychiatric drugs, their reasons for taking these drugs were not the same as those who were in our state hospital. The conditions they had fell more into the categories of substance abuse and dysphoria. Whereas the problems of those in our state hospital fell more into the category of psychosis. And while in the early 2000’s Seroquel was the most expensive cost for our state prison pharmacy, it was not by and large being used to treat psychosis; it was mostly prescribed as an alternative to benzodiazepines to treat insomnia and anxiety. At the time, this new (and highly promoted drug) was considered to be a safer alternative to the addictive benzos.

I wondered whether my experience generalized to our nation’s larger states and cities so it was with interest that I read the excellent series of posts by the blogger 1 Boring Old Man (here, here, here and here). Whereas in an earlier post he seemed to accept the notion of TI, he did some research which confirmed my impressions: it is simplistic to assume from the rates of institutionalization that prisons and jails have replaced state psychiatric hospitalizations. He cites several studies, including a comprehensive report by Seth J. Prins who researched the incidence of mental illness in prisons and jails. Prins found that much of the data are weak and based on self report but his conclusions supported my general observations.

It is too bad that Emanuel and colleagues did not look at this work. It appears that the authors of the JAMA commentary were influenced by the work of the Treatment Advocacy Center. Their first referenced article is by E. Fuller Torrey and Jeffrey Geller. The authors also give a nod to the hospital that Geller has recently helped to open in Massachusetts, the 320 bed Worcester Recovery Center and Hospital.

It is tempting to stop here. But I would not be honest if I did that. For I am living through a transition in Vermont and I see both sides of a certain dilemma. The authors write, “Even well-designed community-based programs are often inadequate for a segment of patients who have been deinstitutionalized.” While I am not sure they are right, I am also not sure they are wrong.

Three years ago, Hurricane Irene closed Vermont’s 50 bed state hospital in one eventful night. The hospital had been struggling for awhile. It lost its Medicaid certification in 2002 and for the next 9 years there was debate over what do. Many advocates claimed we did not need a state hospital while those on the other side argued we could not survive without one. There was no resolution until the legislative session following the flood when the discussion was forced into hyper drive. The Governor initially proposed a 16 bed replacement hospital while opponents argued for a full replacement or even a new larger hospital. As the authors of the Asylum paper note, the push for smaller hospitals comes from several quarters: “Progressive reformers, consumers, civil libertarians, and fiscal conservatives all advocated for a similar goal – the closure of publicly funded psychiatric institutions.” Vermont has no shortage of progressive reformers and the lure of reducing state costs appeals to both sides of the aisle. Due to the way the Federal government funds state budgets, a smaller hospital would bring in substantially greater matching funds for community programs. The hope was that these moneys would enhance our community system of care thus allowing for a smaller state hospital. The legislature ultimately approved a new 25 bed hospital and plans were made to develop enhanced community services.

The ensuing process has been simultaneously exhilarating, exhausting, and,at times, demoralizing. It took a long time to get programs up and running and during this time we had more people than ever before stuck in emergency rooms waiting for hospital beds to become available. This has stretched the limits and patience of our emergency room staff. However, we have also created some wonderful new programs. I now work with a peer crisis team who have taught me more than I could ever have gleaned from a book or paper about the power of peers to help their fellows in crisis. Just their presence in our agency has done more to promote the concept of recovery than any talk or lecture.

But there have been some unexpected and somewhat ironic consequences.

Vermont has fairly strict laws governing the circumstances under which people can be forced to take psychiatric drugs. It is not uncommon for people to be in a hospital for months while their cases are litigated. In years past, those who sought to change the law found their efforts thwarted by advocates with opposing views. When we had a state hospital those individuals who refused drugs were treated there but now they were held in community hospitals. This brought the attention of a powerful force – the community hospital system -to the debate. For the first time in over a decade, changes in the law were made to speed up the process in which people held in hospitals could be forced onto psychoactive drugs. So an effort to increase personal autonomy by reducing access to state hospital beds, has also led to a more rapid legal process for giving a person drugs against his will.

During this same period of time, I have increased my own resolve to try to limit exposure to neuroleptic drugs. Whether you think it is a recurrence of some underlying condition or a withdrawal phenomenon, reducing the dose of neuroleptic may still land a person back in a hospital. When there are few hospital beds, there is more pressure to discharge people as quickly as possible. Avoiding or minimizing exposure to psychoactive drugs involves going slowly – waiting before starting them and increasing the dose gradually. Those principles – caution with drugs vs. rapid discharge – can both be viewed as promoting personal liberty and autonomy but they can also be at odds.

In addition, if a unit has a higher density of highly agitated patients – another consequence of reducing beds – doctors are not comfortable waiting or going slowly with drugs. It does not feel safe. In an attempt to reduce the risk of long term exposure to drugs, I am increasing the risk of hospitalization where a person may end up on a higher dose than when we started. In an attempt to reduce the number of people in our hospitals, we have created units where there is a high density of more volatile and agitated individuals.

But there are ironies that go in other directions. In the Asylum article, they suggest an increase use of “assisted treatment in the community” a euphemism for forcing people to take drugs in community settings. Although there seems to be increased Federal interest in this, there is less enthusiasm in Vermont where when someone does not follow an outpatient commitment order the only recourse is to put him in a hospital. When there are few hospital beds, there is little enthusiasm to pursue this.

I have learned that I do not have an answer. I do not think we fully understand what is happening in Vermont in the sense that many programs are new and this complex system is still adjusting.

I am sympathetic to the concerns and fears of my colleagues who work in the inpatient setting and are struggling with volatile wards. I understand the pressures they are under. And to be clear, I am also sympathetic to the concerns of people I know who are admitted to these units and are sometimes frightened by the behavior of the other patients. The incidence of assaults on these units is rising and while I do not think my colleagues discount my talk about being more humanistic in our work, I wonder if they think that I and others do not fully appreciate their predicament. If I am not successful in keeping 100% of the people I see out of hospitals, if I turn to hospital level care when I think someone is not able to be helped safely in the community, it seems hypocritical of me to blame them for the actions they take to keep themselves and others on their units safe.

It increases my resolve to keep people out of hospital and in that way, I seem to be aligned with everyone on all sides of this debate. But then I circle back to the dilemma about reducing the dose of drugs and increasing the risk of the person being hospitalized once again.

There are some who lay the blame back onto psychiatry. If we had done this right in the beginning perhaps people would not be on drugs. Soteria Vermont was one of the programs funded post Irene and many of us wish it well. But as I read the literature, even those approaches do not work for everyone. And, at least from my vantage point, it seems there will still be individuals who decline every option or are too agitated to be in a community setting.

I communicate with many people who take all sorts of positions on this. For better or worse, I seem to be sympathetic to views that are not in alignment with each other. Lately, I find myself coming to the notion of both/and. Maybe I am misunderstanding or misappropriating that concept to this discussion but it seems we need to hold on as much as possible to a humanistic person-centered approach to helping people in extreme distress. At the same time, we can acknowledge that we will sometimes fail. Maybe some of you would not fail but we are a system of people like me and I know I fail. But then I try again. I am thinking of some people who I have worked with for years. Over and over again, I have tried to work in a way that is as close as possible to that person’s wishes and perspectives. For some, this was always easy and for others we have gradually worked it out. We have found a way to work together collaboratively. But in other cases, I have not been able to figure this out.

This started out as a discussion of asylum. Sometimes, I also wish there was a safe place for people to stay while they work through their crisis. We tried to build that into our system in Vermont and those programs are outstanding. But from where I sit, there continue to be people who can not live safely in our communities. Some do not seem to have the wherewithal to care for themselves adequately and others appear to pose a risk to their neighbors. In some cases, they refuse what we have to offer and for others, we do not have adequate resources. The issue of resources is not trivial. For state budgets, these services are a huge part of their expenditures and we can not do it all. Choices need to be made. The public loses interests in our issues and it can appear to them that our needs are unending.

For me, this remains an ongoing, difficult, and unresolved quandary.

Dr. Steingard, thank you for an intersting and thoughtful article.

In your articles, you repeatedly bring to discussion the topic of people whose behaviour is “anti-social”, yet they refuse ANY known model of treatment.

I want to ask you one important thing, however. So, my question is: does such description fit devoted rebels, dissidents, non-conformists etc.? These are people who are usually described (and treated) as “asocial” and/or “antisocial” not only by authorities, but also by the “silent majority” compliant to authoritarian dominance. Should their protest and resistance be labeled as “delusional” (which, by the way, happens quite often)?

As I have said here already, I’m neither “antipsychiatrist” nor even “anti-drug”. I’m, first and foremost, “anti-coercion”.

Well, in today’s quite coercive society, we can, at the very least, make coercion flexible. I mean that people accused of deeds which are considered “criminal” should be given a choice between trial and treatment. It will let them to decide whether they consider themselves right and want to persist in their conflict with the current societal order, or they evaluate their mental state as problematic and distressful, regret the behavior which they manifest because of this undesirable state, and want a professional help. In such a case, they should be presented with a full spectrum of possible theraupetic options – biomedical, psychosocial, spiritual – with full information of their pros and cons, and make an informed choice. And they should have the right to stop the treatment if they find it unsuitable for them, and face a judicial trial.

Such choice would be better both for principal contrarians who are adamant in thier uprising against the state of affairs which they percieve as unjust, and for genuinely disturbed people who have a conflict with society because of their undesirable psyche which they want to change – but do not have enough inner power to do it, and need a help of more knowledable and experienced person.

Report comment

Thanks for the comment. Although I acknowledge there is no fine line, I am talking about people who are not engaging in discourse which I can follow. I am always wanting to give examples but then constrained by confidentiality. Even in the court system, where they see many people are not not following the rules, they call us in because these individuals stand out as different in a sometimes profound way.

But fundamentally, I think this is what I am getting at with the “both/and”. We should never stop trying to engage in as collaborative and respectful way as possible.

Report comment

Sandra,

I continue to be puzzled by why you post on this site. I’m sure you are aware that almost all the users are against enforced psychiatry, yet you are always in favor of it. You mention “a safe place to work through a crisis” as if you are unaware that psychiatric hospitals are not safe at all. They immediately harm a person’s sense of self (leading to “tainted identity” that almost never can be erased), they put any person in danger of a thousand forms of physical harm, iatrogenesis, etc. and they never have enough facilities or personnel for actual psychotherapies that have been shown to help people in crisis.

As for your not being able to clearly explain what you mean by individuals not making sense to you, when you resort to the “confidentiality” excuse, it reminds me of the Catholic church refusing to explain things based on the doctrine of “mystery.” Maybe I’ve misunderstood you?

I’d love to hear what you have to say in response.

Report comment

I’m not entirely certain what you mean by users (readers? commenters?) but it almost sounds as though you’re suggesting that their agreement is a requirement for blogging here… that’s definitely not the case. I think I can speak for everyone on the staff of MIA when I say that we value Sandra’s perspective — a perspective that is much more thoughtful and nuanced, in my opinion, than “always in favor of enforced psychiatry” — and are grateful that she chooses to share it here. To really change things, we need to be aware of the dilemmas and unintended consequences that may result when people attempt to put principles into practice on the ground, in complex and less than ideal circumstances. And we need to understand how a person’s thinking can evolve over time as they grapple with these issues. I’m glad that Sandra is willing to be so open about her process here, because I think it can serve as a model to others in the field who will hopefully come to change how they practice psychiatry too.

Report comment

Thanks, Emmeline. It is a privilege to have this opportunity.

Report comment

Thanks, Emmeline, for replying for Sandra. I can see that Sandra would only be available to respond to compliments, not questions.

Report comment

Comment removed.

Report comment

Ann,

I was going to reply that I blog here because I was invited to do so. Emmeline seemed to address that before I saw your comment.

As for your other comments, I read them as comments that did not necessarily call for response. However, since you seem to want one I will try.

I do understand that people are harmed by being forced into hospitals and I try to do what I can to avoid that outcome. And while I do not agree with your characterization of me as being in favor of it, I admit that I can not always find other alternatives. I recognize that this is not an adequate explanation for some. I stand by my decision to not describe particular situations out of concern for privacy and I understand that you may find this a poor decision that gives the appearance of avoiding open and honest discourse.

Report comment

Sandra,

I do think it more appropriate for you to reply to me rather than having “followers” do so. I think that any paid professional who posts articles on this site should feel it incumbent upon them to engage in dialogue with commenters. Otherwise it is the same old power differential that keeps bad ideas in practice everywhere.

Did it ever occur to you that the very power differential inherent in you talking with a ‘patient’–i.e. that you have the power to incarcerate said patient–might have something to do with communication difficulty and breakdown?

If I were in your position, I would quit the whole system and set up something closer to what my conscience tells me is right. I say that having forfeited a large pension when I had many years in my profession and could write my own ticket. I simply couldn’t stand to be part of a conveyer belt that took to many people straight to hell. But I’m broke, Sandra, so you can see it is not the choice for everyone. Good luck with your own choices and I hope you feel more peaceful as you make them. At least you’re struggling, which puts you ahead of most.

Report comment

Sandra,

“And while I do not agree with your characterization of me as being in favor of it, I admit that I can not always find other alternatives.”

Perhaps, the alternative is not to stigmatize people with fictitious “disorders” and drug people with toxic drugs that cause the “mental illness” symptoms in the first place?

Perhaps, helping people is about actually listening to their real life concerns, and psychiatrists going to the police with crimes that have been committed against people, rather than just stigmatizing people with fictitious “mental illnesses” and tranquilizing them with toxic drugs?

Report comment

The one thing that I appreciate about Dr. Steingard is that she doesn’t pretend that there are any simple answers to the problems that people labeled as “mentally ill” face and deal with on a regular basis. I appreciate the fact that she admits that she doesn’t have all the answers, unlike so many of the psychiatrists that I deal with on a daily basis in the state hospital where I work.

I believe that it takes a certain amount of courage and guts to stand up and point out that there are no simple answers. All too often, I find myself reaching for the simple answers and solutions to problems that are not cut and dried, black and white, and they are certainly not simple at all. I also believe that at times, many in our movement only want the simple answers.

I appreciate Sandra’s willingness to show that she struggles with all of this, as any clear thinking individual would struggle with the issues.

Report comment

Ann, “I’m budding in” as I was just so enjoying the more positive exchange happening here that so often we don’t see when “professionals” blog. As a consequence most doctors won’t blog here as the negative comments feel like bashing rather than dialogue. I don’t think things will change if we can’t have an open and respectful forum to dialogue and for others who may be curious and or wanting to learn and join the discussion can’t do so without attach. I’m not saying your comments in this chain or attacking but they are a little bit. That said I want to say I wish there were more doctors like Sandra working in the mainstream as that in and of itself would start to change “business as usual” we need the “good guys” working in the belly of the beast!

Report comment

Psychiatric hospitals are worse than any hellhole save maybe Guantanamo prison and other places of torture. It’s beyond ridiculous someone can call them “safe”.

I’m a psychiatric surviviour and was tortured in such an institution and I know for a fact that is standard practice. I despise any attempt to defend torture, no matter if it’s called “enhanced interrogation” or “psychiatric treatment”. There is in fact a direct link between the two, obvious for anyone with a bit of knowledge about the history and sadly present.

Report comment

Isn’t it odd that “enhanced interrogation” of prisoners and supposedly benign and benevolent “psychiatric treatment” are the same thing? How can that be?

Report comment

Comment removed.

Report comment

“I mean that people accused of deeds which are considered “criminal” should be given a choice between trial and treatment.”

Accused? How about they get a trial and at sentencing they get the choice? Maybe we should stop with the Minority report already. You’re only a criminal in the eyes of law when you’ve been adjudicated as such.

Report comment

Thanks! If this was easy to figure out, it would have been done a long time ago. Sharing perspectives from different sides of the debate is important and valid. My feeling is that community-based programs have never been funded sufficiently to be as effective as they could be, and that models like Soteria are given up on far too soon. They’re never treated as more than pilot programs — and expected to produce instant results by people with vested interests, like psychiatrist, who can’t show instant results either — if they can show any results at all — and who feel threatened that someone else would set up a model of support that isn’t under their own control. If someone had a physical illness, like cancer, everyone would expect that it might take years to ever solve it and for that person to recover. But with mental difficulties, there’s no realistic picture in people’s heads. Some people work through their troubles quickly, while others need time, and maybe a lot of time — but we’re so fixated as a society on a quick fix that we expect instant results. It can be scary to deal with people who seem out of control, and if drugging them and locking them up relieves the public’s anxiety, the public will go for that option, and community-based programs will never get a chance to show their long-term outcomes. And I’m quite confident that the psychiatric establishment, given a chance, will pay no more than lip service to community solutions while actually undermining them at every step, whether by strangling their funding (every dime lost to community support is a dime not collected for appointments or medication) or by coopting them and turning them into yet another channel for coercion — turning them into the deceptively named “assisted” outpatient treatment programs. An object lesson is the history of state asylums. The original success of asylums was a result of the respectful and humane environment of the moral treatment model brought from Europe, where everyone was respected and no one’s freedom curtailed, and people had time to recover. It was so successful that state hospitals were built all over the country. But what happened next was that they were gradually corrupted by outside forces. Doctors — the self-appointed experts — took over and began to impose their treatments: cold baths, spinning, wrapping, insulin shock, electroshock, lobotomies, disabling drugs — and they brought with them the whole hierarchical structure of coercion and control, of the “expert” who supposedly knows more about the “patient” that she does herself, thus justifying their control. At the same time, the hospitals became a dumping ground for society’s undesirables. While those who recovered were able to return to the community, only those who didn’t were left behind, and they accumulated in number. Other undesirables — hopeless drunks, and teen rebels, and the socially disobedient, and blacks who spoke out for their civil rights, and communists, and unmarried pregnant women — were confined there, and kept there, because they were committed by other people who had been granted that coercive power. (The way the Soviet Union used mental hospitals and diagnosis and drugs should be a lesson to us all.) The whole purpose and structure of the asylums was subverted. If asylums were to return in something that resembled their original form, where it was about respect and freedom and being part of real community, I’d be all in favor. That would be a haven, not a prison. But if asylums return in the form they had in the past few decades, I have little hope that they will help anyone recover. Are the old asylums any better than the de facto system of “mental health care” that now dominates the country in the form of the prisons and jails? I don’t think so. Thanks for speaking up about the complex issues involved and your concerns.

Report comment

Hi Eric,

You make some very good points including the notion that it is easy to romanticize the notion of asylum. My one quibble is that I do not think it is the psychiatric establishment per se who strangles funding for community services. Some of us are part of that system. I think the psychiatric establishment sometimes undermines the credibility of alternatives and that is important to acknowledge.

Report comment

Here is some reason alternatives are under mined. One is, mentally ill people are not seen as people in need of help or support, but society wants to do them in and get rid of them for not living up to standards. Therefore they don’t get medical treatment, they can controlled, drugged, and imprisoned which is also very profitable to the unions who lobby for this type of stuff and the police state and private companies involved. Next up is, pills happen to be patentable, and profit can be had by each person drugged, tax dollars and insurance money can be siphoned off from society into the hands of rich wealthy investors, and everything in America is for profit. Anyway imagine being able to control what people think is treatment, get them to even exclusively prescribe pills, because its far more profitable and easy than letting the money go towards actually creating a solution or paying for psychotherapy, housing etc..

Report comment

Maybe we don’t need psychiatry at all? It seems like as far as “evidence” goes your drugs make people worse, your coercive interventions make people worse (personally they made my try to commit suicide which has it succeed would have for sure been blamed on my severe mental illness and not on the torture that people who subscribe to coercive psychiatry inflicted on me) – what’s the point?

You can’t tell who’s mentally ill, you can’t define mental illness based on any objective criteria, you serve as an institution of social control of undesirables and you punish the victims of abuse with physical assault, labelling and brain-washing.

Psychiatry is a useless entity – in contrast to other, somewhat legitimate areas of medicine, it can show no improvement whatsoever as the current “epidemic” shows. So why bother?

The answer is not in medicine, is in politics and social change. Psychiatry is a part of oppressive system that should be abolished.

Report comment

I agree with Eric’s concerns, as well as B’s comment that, “You can’t tell who’s mentally ill, you can’t define mental illness based on any objective criteria, you serve as an institution of social control of undesirables and you punish the victims of abuse with physical assault, labelling and brain-washing.”

I was defamed with a “mental illness,” unbeknownst to me at the time, based upon the lies of a genetically Russian ELCA pastor (a religion that originated in Germany), so that this pastor could cover up the sexual abuse of my child, and his denial of my daughter a baptism at the exact moment the second plane hit the second World Trade Center on 9.11.2001.

And perhaps also because I come from an ethical American banking family, and I am now disgusted to learn that our country’s banking industry has been taken over by the “banksters” that our founding fathers warned about, and our country is now being ruled by those who financed the Nazis.

I hope the psychiatric industry, that is currently willy nilly defaming everyone they can get their mother f-cking hands on to, with scientifically invalid “mental illnesses,” rethinks the wisdom of whom they are actually working for.

Report comment

Btw, I don’t mean this as a personal attack on you (although as a victim of coercive psychiatry I see you as a torturer every time you subject someone to this atrocity – there is just no “polite” way to put it even if you or some other people who may not have the experience see it as offensive). I appreciate that you are trying to make the camp a little more bearable for the inmates and prevent more inmates from being shipped in – there’s a value in that. But it also legitimises the existence of the camp and that I can’t agree with.

Report comment

Thank you Eric for your thoughtful comments.

D. Steingard, my point is similar – how long has Soteria house Vermont been operating? Think how many years it took for the people in Harrow;s studies to recover.

People in extreme distress need safe and humane places to go through their distress, possibly for years. They need it now, desperately. Families desperately need some safe place to take their loved ones when they need a break etc.

What is criminal is that people can be forced to take medications which could hinder their long term recovery. AOT results do not cite research that relate to `recovery’ (e.g. improved cognition, independence etc.) but to things like decreased incarceration, homelessness etc, that would be the result if a person was well, but also if they were sedated!

So please, let all of us who are worried about the long term effects of antipsychotics work together to focus on providing a system that includes forced safety for the severely ill -when necessary – that is independent of forcing drugs that could harm or hinder recovery. Once people are safe, then the discussion of whether or not medication is used can be a choice of therapy If a humane asylum as described by Eric is created and closely monitored , it could be an important part of that picture that stops forced medication.

Forced medication, given the state of the research, is the real urgent problem now.

Imagine if people were being forced to take street drugs which everyone acknowledges can seriously harm people – imagine how that would play out in the news.

Thanks, as allways for the time and concern you spend on these issues.

Report comment

I just wanted to add that having safe places to take people in extreme distress to, takes away any ‘justification’ of AOT (e.g. with proper supervision and care, noone could say these people were a danger to themselves or others)

I just wanted to add that a proper ‘asylum’ could create the environment needed for recovery. Now, people who believe medications hinder the recovery of their loved one try to provide a ‘healing home’ in admist a very prejudiced and misinformed society.

A protective setting could be set up so a person could work gradually to their independence – go by themselves to exercise or swimming or possibly to little shops etc, , go to work or school settings with people other than their family; knowing that there were trained and humane people who could step in when their stress became overwhelming. Maybe a percentage of people would make this their permanent home (research indicates around 10 to 15 %???), and the other 85% could eventually increase their independence to return to the community. Maybe some clients would be ‘day visitors’ living at home with their families, or parttime residents or working there as peer counsellors or in other jobs as they help the newly or more seriously afflicted.

Report comment

While I think you idea is a fine one, I nevertheless know people who decline these options.

Report comment

Is that kind of an option available in Vermont?

There are no places where I live where people could go to when they are in extreme distress, without having to take anti-psychotic medication. And there are no services that go into the home that do not involve forced medication. So having this option could provide enormous support to families who fear what the science is saying about antipsychotic medication.

And at least for those who decline this option, if there had to be `force’ it would be a better option than AOT, prison or hospitalization with forced medication.

Report comment

If someone is not free to decline an option, it can no longer be accurately described as an option.

Report comment

Good point, Sharon.

Report comment

“I nevertheless know people who decline these options.”

So? Should that not be their right? If they are indeed criminal and prefer to face charges for their behaviour it should be up to them. If they’re not criminal you should leave them alone.

There is nothing worse for one’s mental health than loss of freedom, dignity and right to one’s mind and body. Which is all coercive psychiatry does. It is torture.

Report comment

B,

Your argument- to prosecute people if they are breaking the law- is what is happening, according to those who believe in the concept of transinstitutionalization. This blog was a response to an article decrying the fact that rather than put people in hospitals we are puttin them in jails. We have many fewer psychiatric beds in the US now than we did a few decades ago. I think that is an unassailable fact. But on all sides, no one is happy about our mental health system. The authors of the commentary suggest building more hospitals. While I do not think you are suggesting we build more jails, I am not sure what it is you do favor.

Report comment

@ Sandra:

“While I do not think you are suggesting we build more jails”

I don’t because it’s a false choice: there are many things which are legally criminal which should not be and people should not be getting locked up for them in any institution. Many people in US are locked up on bs offences, often involving drugs (which use very often already put people in the “mental” category). Let these people out and we have half of the problem solved.

Secondly, the narrative itself is false: many of the people who get “diagnosed” in jail are getting diagnosed because they are in jail. Or they would never be in jail if they didn’t have a diagnosis because people who are labelled are treated worse by the justice system (“the dangerous mentally ill” – the stereotype which people advocating for coercive psychiatry propagate).

Thirdly, I don’t think that prisons are worse than psychiatric hospitals – in fact they may be better. Of course US prisons are not particularly known for their “humanness” but I know a situation in Austria where I’d take prison over psych ward 100% of the time – nobody would be drugging me to my gills against my will and I’d know what is the latest date I’m out – people who get locked in psychiatric hospitals even for small offenses end up doing more time than if they went through the normal justice systemand when they get out is usually based on “the psychiatrists said so” (there was recently a study which was reported in the press which addressed that).

Therapy in psychiatric hospitals is a sick joke, especially if you are not interested in being there in the first place. It always equals drugs.

Report comment

Sa: You wrote: :Now, people who believe medications hinder the recovery of their loved one try to provide a ‘healing home’ in admist a very prejudiced and misinformed society. ”

So we build asylums to compensate for a very prejudiced and misinformed society? After we pour billions of dollars into building asylyms, prey tell, when do we direct resources into the problem of reeducating people and changing our culture so that is is inclusive and tolerant?

You are also wrote: “Maybe some clients would be ‘day visitors’ living at home with their families” Hah! From experience, having a loved one forcibly committed to state hospital 200-500 miles from where a loved one was born or raised makes your idealist vision ridiculous.

Report comment

Yeah. The description of a “perfect asylum” fits the flowery description of some psychiatric hospitals. Sounds good on paper until you go there and see for yourself. Institutions, especially those where some people have power over others, ALWAYS -re-create the Stanford prison experiment. That’s human nature and good intentions pave the road to hell.

Report comment

OK, so– Yes, psychiatry did it. The mainstream won’t act against its immediate judgment of its own best interests. Very specifically I mean that however collegiate the various groups have to be, who get their credentials to have this perceived and real authority, in order to leave no question of substance about where there loyalties lie, that is the prime objective and it shows.

But all these terribly intricate problems are not part of my material purposes for earning my living. Positive strategies at this point seem like the joke they are guaranteed to be faced with the enormity of the problem. But if everyone got due process and could only be held against their will according to it, and that means in jails not psychiatric facilities, we’d have half the problem to deal with. The propaganda and stupidity of the hailing of revolutions in psychiatry as a way to get the public on board, that and the sum total of inconsitent messages we are told “help fight stigma” but really don’t–that also would be halved if the coercion was both made explicit as the guiding purpose of evaluations in the first place, and then limited by separating the proven offenders from the difficult companions on purpose. These are ethicists you say?

Report comment

travailler-vous :

I’m not following your logic. Could you try to explain this a second time? My intuition is following you and is saying a big “YES” but my logic is not concurring.

Report comment

Madmom – That’s the right way to put that, that my logic is something else to follow. Sorry, as mainly it is not reflective of good communication, but is shorthand for how I would think it over in the ideal thinking state: but I can explain, except I want to read the thread and go back to to reread Jill Littrel’s last post which is in many ways related. There, too, I was typing out what I myself thought helped me to keep the ideas together, alluding to the difficulty and posting a link to British female philospher who I rely on for constructive critique of psychiatry. The asylum vs. jail debate is farther from my own material purposes in life than the hospital, which I consider most unfortunately unusable for my own good, but which is where my lived experience comes from for whatever I can do to understand the views under discussion. Both Dr. Steingard and Dr. Littrell constantly make extensive revisions of their version of needed reforms and are each sharp in their own way and I don’t want to add an explanation of the logic of this flurry of doubts and concerns of mine without making sure I get my ideas clear. Especially since your interest is expressed on behalf of your daughter and since the moderator has to interpret the verbiage with the same problem in doing so as I left you.

Thanks for asking, and I’ll get to it. For starters, I presume that we are talking about reforms for the “failed paradigm” of behavioral healthcare, though, if that helps in the immediate moment. Also, I wanted to recommend a fine book to you that I just started and that I believe you would not want to wait on yourself, called “Imagining Robert” by Jay Neugeboren. He’s not at all square and lives as a writer; the story regards his fraternal relationship to his brother as he has gone through treatment for schizophrenic overwhelm. Neugeboren brings all the right questions to the table even when he’s too kind and encouraged by NAMI and MHA and those organizations or when he’s not putting quotation marks around Mental Illness and so on.

Report comment

Madmom – So let’s see about this trip back in time to re-explain. I’ve gotten enough distance from the initial motives to see what I h-o-p-e-d to have said. Whenever something gives me greater chance to hang onto stability, which does tend to be what follows intense flashback episodes, I end up surpised at how little my mind has changed about how bad the services on offer are. But my sense of humor comes back in better condition and my head’s more clear. So…

My point derives from the libertarian critique of mainstream efforts in both academic and clinical behavioral science, of everything from publication to court testimony. The system is just one grand crying out for permanent entitlement first and foremost, and patients are second in line at best. Really, it is not hard to see that the push of the allied mental health industries is wholly toward the formulation of a medico-therapeutic bureacracy that blurs all distinction between private enterprise and government “aid programs”. Wow, that shows prominently in the work I’ve seen underway in mental health wards and community mental health centers and doctor offices, come to think of it.

The other idea is that the same people who gave us this failed paradigm are very nearly the ones who will give us the next version. The ethicists today are representatives of their employers and tomorrow they still will be. (And I think that “failed paradigm” has got to suggest “flawed from the outset” and “rotten to the core”, etc.)

I find myself able to interpret my first post line by line, but it’s not of enough interest in comparison to just expressing myself anew, since now it is easier. Meanwhile, thanks for asking in the first place. It says something nice about your attitude that you’d care to make out the meanings in connection to the intentions for my trying to communicate them!

Report comment

Travailler-vous: Thank you for revisiting this post. I like how you express your ideas and I appreciate the recommendation of the book (which I was reminded of when I re-read your original post to put your second post in context) Are you bi-lingual by any chance? It would be nice to keep in touch. You can email me at [email protected]

Report comment

madmom- I got you on that, so if you want to have Emmeline pull down your email address you can probably get her to. I am–maybe unmistakably– American, and although I could have been brought up with biracial consciousness, it escaped emphasis likely as not because the language had been let go down through the generations. Typically, I know only the language that I have to know.

Report comment

“These are ethicists you say?”

I love the people who are making up great humanistic theories from the midst of their ivory towers. Completely ignoring the totality of human history with the special emphasis on the XXth century. Yeah, I’m sure the new day asylums will be nothing like the old day ones. I mean the nature of humanity has evolved so much during the last… well that would be 10seconds because even the current scandals in psychiatry and beyond show we are not past the Milgram and Stanford prison experiments and worse.

Report comment

Thanks for the piece Sandra. I agree that there should be a” safe place for people to stay while they work through their crisis.” The complexity arises when we talk about the varieties of crisis.

Here in Portland, the various hospitals have found themselves increasingly squeezed and are losing large amounts of money in their acute settings. This is largely due to the fact that acute hospitalization tends to involve people who have limited or state insurance. This leads to poor reimbursement while funding the payroll for all the doctors and nurses is exorbitant.

For this reason, the largest hospitals are pooling their moneys to centralize and create one large inpatient facility in Portland with its own psychiatric ER. This is mainly a cost savings measure but points to the inherent problem with crisis mental health care. Generally, the medical system is far too expensive to “manage” crisis. Its just not a model that has made fiscal sense.

We are in desperate need of alternatives that are not only cheaper, but far more humane. One of the main problems I see is that most anyone in crisis is funneled into one monolithic system. Those who are high, drunk and acting bizarre and agitated, someone with dementia who is violent, someone who has stopped taking strong neuroleptics, people experiencing “first-break” episodes- all get funneled into this one system and tend to receive very similar care- psychiatric drugs and often a short stay of a few days before being sent out for services (generally lacking) in the community.

We need systems where we funnel a number of these folks to systems of care that do not prioritize med management. This is especially important for “first break” folks. In my perfect world there would be “asylums” designed to allow crisis to run its course without medical intervention. But my second best choice (and likely more realistic) is to promote a non-interventionist model for first-break in a hospital setting where people are not immediately started on strong doses of neuroleptics, or at least offered a choice for selective use.

In this way we may not create a group of folks who require long term med management. Once this happens, folks often cycle in and out of hospitals due to intermittent and understandable “non-compliance.” Then it becomes much harder to create non-medical alternatives for crisis. I believe we have to really start at the beginning when people first start taking strong meds and try to avoid that as much as possible. Once an individual has been taking psych drugs for a while, it is deeply challenging to offer alternatives that don’t in some way involve psychiatric intervention, even if it means to help taper someone safely as you have been talking about. And when someone is agitated and has been cycling on and off meds, soteria and respite models are not effective. We have to go the root and start from the beginning and address how this epidemic has happened. Trying to fix it midstream is deeply challenging.

Report comment

I just want to add although starting at the beginning would be ideal, people on their second break or third break or whatever, should also be given the opportunity to be in a safe place where the crisis can run its course without medical intervention.

The people in many stories of recovery started off on drugs, or had many relapses, or like Katherine Penney, went for years prior to recovery. Somehow -whether it is in an ‘asylum’, soteria house, healing home or hospital people must be allowed the chance to work through a crisis without medical intervention if it seems that this is their best chance for recovery.

Report comment

…..when I say medical intervention, i actually mean forced medication

Report comment

Right on! Great point, Sa!

Report comment

“[W]hen someone is agitated and has been cycling on and off meds, soteria and respite models are not effective. We have to go the root and start from the beginning and address how this epidemic has happened.” And realistically, it stated with defaming and drugging people with scientifically invalid “disorders” and mind altering and toxic drugs in the first place.

Report comment

Forgive the typo, “it started…”

We’re dealing with an iatrogenic problem, and an iatrogenic epidemic actually, propagated and supported by the unethical few currently in charge, and whom actually profit off these crimes. The psychiatric industry needs to wake up, your drugs cause the DSM disorder “symptoms.”

Report comment

Jonathan: You laid it out brilliantly. Creating choices and alternatives while keeping costs down. If people who are undergoing a crisis, aren’t ‘medicalized’ to begin with, perhaps we could avoid the enormous costs of funneling people through the medical system. The medical system is ballooning out of control in in general, not just in the mental health side. A culture shift needs to happen before we can stop viewing all people who are confused, disoriented, scared, angry, etc. as in need of ‘medical’ expertise/treatment. The only reason why parents like me take a child who is experiencing their first ‘break’ to the ER where they are introduced to neuroleptics, restraints, and where they are inflicted with unfathomable psychological harm, is because we are lacking in imagination due to the homogenous way we have been raised. Plus, we are products of a generation that was raised to believe that doctors were trusted and wise authority figures, like Marcus Welby. We had no idea the level of mediocrity that psychiatry had become due to commercial forces, lack of imagination, and scientific curiosity.

Report comment

“parents like me take a child who is experiencing their first ‘break’ to the ER where they are introduced to neuroleptics, restraints, and where they are inflicted with unfathomable psychological harm”

And then psychiatrists complain that there are people who don’t want any options. Is it so difficult to understand that some victims actually have the strength and dignity of resisting oppression. And once victimised they have no interest in becoming pets of “good-meaning” psychiatrists.

I just don’t understand how can you not understand that and see it as unreasonable or even “lack of insight”. the only person lacking insight is the psychiatrist, who apparently lacks empathic skills to understand this.

Report comment

Apparently imagination which includes empathy and a sense of humor are severe psychoses. Psychiatrists are certainly devoid of them. Once they get through messing with your brain you will be too!

Report comment

Thanks for your comments. I have been thinking lately that the way to stop current psychiatric practices — the drugs that debilitate and eventually kill people, which consumes simply enormous public resources, and the extremely expensive recurrent hospital stays and endless psychiatric bills — might be the way to attack the system and put something else in its place. For instance, just to use my own case as an example: A hospital stay, even a brief one, costs many thousands of dollars. When I became psychotic, I cost the system more than $10,000 in just a few days. After I became psychotic, I was given disability — at a cost of more than $1,000 a month. Since I was prevented by the drugs from ever truly recovering, and in fact further disabled by medication even after the real psychosis passed, that meant it became a permanent expense to the public. (In the interests of total disclosure, I’ve only just completely eliminated meds and haven’t yet rebuilt my life enough to get off it, even though I’m getting there.) Psych meds also come at a premium: more than $700 a month for the single drug I was on, and I was one of the lucky ones who resisted being sucked into the system of polypharmacy, where you might be juggling numerous expensive meds. Because that antipsychotic stopped my metabolism, it caused immense weight gain and high cholesterol and high blood pressure and high cholesterol — and now we’re talking more bills to medicare, not only for drugs (insulin alone is $350 for a supply that might last as little as a month, but that really does vary, so it’s only a ballpark number . . . but then there’s the other stuff, which added up to at least a $100 a month.) Now add doctor’s bills — for follow ups and dealing with new problems as they emerge. Even now, I am dealing with the fallout of what happened to my body, and though I have eliminated the big-ticket items like antipsychotics and insulin, the expenses haven’t ended. And there’s another cost: while disabled, social security paid my child support to the tune of $500 a month. So: instead of my returning to being productive as soon as I might be able, for many years I have been an enormous drain on the system — to the tune of roughly $30,000 a year. And since I haven’t had to be rehospitalized or had multiple psych drugs, I suspect that I’m one of the cheap ones.

Perhaps what we need to do is reframe the entire public debate away from the personal costs of current psychiatry, because there seems to be a kind of blind spot about mental difficulties in our country. The public debate is framed mostly by fear of what those with mental difficulties are going to do, and it is from this fear, unthinkingly played on by the media, that psychiatry derives its power. Desperate people will turn to the people who present themselves as having the answers, and in our society, that’s psychiatry. The human picture of what actually happens to most people who come under the influence of that system is completely obscured. Psychiatry’s harms are swept under the rug, maybe because there is this constant triumphal march about their supposed progress, how they’re supposedly helping, while their actual record is almost never examined. That ten years on antipsychotic shortens your life expectancy by five years, for example. And maybe the way to attack the system is to reframe the discussion outside their rhetoric of illusory scientific progress and cast it in terms of actual economic costs. If we can contrast the public cost of community-based models like Soteria, or even the costs of a program like Open Dialogue in Finland, we might discover that all of a sudden people will stop being distracted by psychiatry’s rhetoric and become more openminded to examining actual outcomes. Talking money might wake people up to shift the model away from the current system and get us the funding we need to set up something that works — based on humane conditions, mutual respect, no forced medication, and community support — long enough for us to prove on a large scale that it works.

Report comment

Eric,

This is such a great post. I hope through this whole discussion a movement to provide funding for alternative services on a larger scale will be born.

Dr. Steingard,

Thank you so much for opening this discussion. I think the fact that you continue to work as a critical and caring psychiatrist within the system, without always having the adequate supports available to preserve safety, is truly brave and honorable.

I think as a family member living somewhere where there is inadequate support for my loved one, I can truly understand the dilema where one might have to choose the hospital Hopefully recovery for our family will continue in the positive direction it is going so we will never again have to face that decision.

Report comment

Eric:

I completely agree with everything you said. My daughter’s ‘treatment’ has cost the taxpayers and our private insurance company close to 1 million dollars, in five years, not including her monthly disability checks of $1,200. For a fraction of this cost, she could have been directed to a program delaying her exposure to harmful neuroleptics during her first break, and received peer support, food stamps, a bus pass, supported housing, and college tuition. I am certain she would not have come off the hinges this way or have a criminal record but would now be a productive member of society. Instead, her confidence is crushed and the psychological harm of being recommitted and forcibly medicated again and again and again is beyond description

Report comment

“In the interests of total disclosure, I’ve only just completely eliminated meds”

Congratulations. Such good news. I hope everything goes well and you’ll be able to recover permanently :).

Report comment

Great comments from all here and I just want to continue on with what madmom says. Imagine a campaign where the expenses for “helping” someone is tallied up. Put a monetary figure on each person in terms of hospitalizations, psych drugs, health complication medicine and surgeries, disability checks, etc…

Call these folks the million dollar man or million dollar woman. Then describe how that money could be spent…as you just did Madmom. Then simply ask…is this how you want your taxpayer money spent?

Report comment

I agree, Eric, our society’s current “mainstream” unethical manner of “social control,” which results in covering up the crimes of the unethical currently in charge, is absurdly expensive and unjust.

As a society, we need to learn of the lack of scientific invalidity of today’s psychiatric “illnesses,” and that today’s fictitious “diseases” are no more credible than were the fictitious “diseases” of the Nazi’s. And this includes the 1% and those connected to them like the religions. Treating all others as one would personally like to be treated, is of paramount importance, instead.

Report comment

Eric,

I agree that approaching this from an economic perspective will have some traction. As I noted above many disparate groups come together when there is a potential for cost savings. We need good data to support that. But we also need to show that short term intensive costs (let’s say in the form of intensive support for those experiencing psychosis) might yield longer term savings(as you note above in reducing the chance of a person being on disability).

Good luck with your ongoing recovery!

Report comment

Warning: Reading the following article will probably make your blood boil.

Drug companies and Schizophrenia: Unbridled Capitalism meets Madness

Loren R. Mosher, Richard Gosden and Sharon Beder

http://herinst.org/sbeder/corppower/drugcompanies.html#.VMV3bId0yfA

Report comment

Thanks Donna,

Fabulous perspective of what was going on in the psycho / pharmaceutical industries at the turn of the most recent century, I appreciate the link.

I was surprised by the Whitaker quotes:

“Zyprexa” … “It’s a potential breakthrough of tremendous magnitude.”(Whitaker, 2001, p.260-61)”

“Or as the Los Angeles Times (1/30/98) put it: ‘It used to be that schizophrenics were given no hope of improving. But now, thanks to new drugs and commitment, they’re moving back into society like never before.’”(Whitaker, 2001, p. 259).”

But I suppose they prove why Whitaker’s current, thankfully, like Sandra’s, “are a perspective that is much more thoughtful and nuanced … than ‘always in favor of enforced psychiatry.’” And their current perspectives are of concern to the mainstream psychiatric industry. Since they are much more well researched, critical, and open minded, than that of the perspectives of most mainstream psychiatric practitioners.

As a person who was flipantly defamed as a “paranoid schizophrenic,” “depressed by self,” and “bipolar” (all within three weeks, and unbeknownst to me at the time based upon gossip from others and with no personal or family history of any mental health issues) by a PCP and psychologist, who, I later learned from their and others’ medical records, wanted to cover up the PCP’s husband’s role in a “bad fix” on a broken bone of mine, and the medical evidence of the alleged sexual abuse (with medical evidence) of my child for the psychologist’s pastor and/or his friends.

I will definitely say we need the critical voices of the psychiatric industries’ unchecked power within our society. And we need to rethink our respect of all those professions that, when I was a child, were formerly respectable. My personal experience implies we’ve ended up with the psychopaths in the formerly respectable professions. And a decent pastor did confess to me that I’d dealt with “the dirty little secret of the two original educated professions.” Which I guess implies that the religions and medical community were never actually respectable?

I personally think we need to rethink the wisdom of our forefathers, and the importance of returning to a society of “checks and balances.” I know the “antipsychotics” can cause “psychosis,” in a healthy person who is inappropriately put on them. Perhaps force medicating anyone with them should not be the legal right of any doctor for any (especially unethical) reason, particularly since every person reacts differently to these drugs, and they’ve now been proven to be toxic in the long run for all people?

Report comment

Soneone Else,

Thanks for your encouraging comment about my link to the great Dr. Loren Mosher and colleagues with an excerpt from a highly acclaimed book on “schizophrenia.”

This rather short excerpt does a superb job explaining the out and out evil corruption by Big Pharma of all those in power from government, medicine/psychiatry, academia, the supposed watchdogs like the FDA, NAMI and other drug company front groups, the media for the most part, advertising and promotion, schools, the courts, familes and society at large.

I hadn’t realized that Big Pharma was actually literally behind the forced treatment agenda to further expand their lethal neuroleptic drug markets while preying on children, the elderly, pregnant women and babies in utero and any other breathing (if only barely) human being who could be forced on these poisons for their insatiable greed, power hunger and sadism. Of course, this makes sense when one considers that Dr. Robert Hare, world authority on psychopaths and consultant to the FBI, agreed with the author of the book and DVD, The Corporation, describing its evil agendas and “behaviors,” that many modern day “corporations” as well as those leading them could well be described as psychopathic (or just plain evil, intraspecies predators).

Of course, Jim Gottstein, J.D. gives some involved the benefit of the doubt when he uses the terms duped or complicit describing this debacle, meaning that not all involved were aware of the predatory Big Pharma/biopsychiatry KOL/APA agenda behind the new “magic bullet” supposed wonder drugs or second generation neuroleptics with the best corporate spin money could buy. Even Bob Whitaker said he believed this great miracle story until David Oaks, former Director of Mindfreedom, encouraged Bob to investigate the history behind psychiatry’s great DSM and neuroleptic wonder drug “success” and the rest was history as Bob explains on a blog about Oaks being a great influence on him. And this excerpt doesn’t even touch on the next monstrous invention and expansion of the bipolar fad fraud described in Dr. David Healy’s MANIA: A Short History of Bipolar Disorder, that demonstrates that the DSM III and IV addition and expansion of this latest garbage can “sacred symbol” of psychiatry could be used to prey on one and all including perpetrators and victims, Axis II and anyone but the “kitchen sink” to push the lethal neuroleptics and the bogus “mood stabilizers” or reinvented epileptic drugs for a bogus theory that bipolar and epileptic seizures have similar paths. This also coincided with the nefarious Texas Medical Algorithm scandals to push the toxic second generation neuroleptic drugs on Medicaid programs nationally that has led to a vast number of children in the state welfare and orphaned children programs being on these poisons. Fortunately, in recent years there has been a public and media outcry about this toxic over drugging of such vulnerable children thanks to Senator Grassley exposing the child bipolar overreach to justify toxic neuroleptics for children by Joseph Biederman actually working on behalf of Johnson & Johnson. Biederman was supposedly doing an NIMH government study while promising J&J positive study results of their neuroleptic drug before the study was even done, which is illegal especially with an NIMH grant, getting him the usual slap on the wrist despite being responsible for the death of toddler Rebecca Riley and similar victims thanks to his bipolar toxic drug cocktail protocols that single handedly caused the child bipolar epidemic. MIA recently posted an article about how this child bipolar epidemic came about mainly in the U.S.

I guess I was pretty naïve not to realize Big Pharma’s role in the forced treatment agenda, which makes the likes of Torrey, Jaffe, Murphy all the more dangerous.

You cited the quotes by Robert Whitaker as puzzling, but these are actually quotes by the perpetrators quoted by Whitaker in his great book, Mad in America, when Bob first came to realize these sordid truths about the great claims of progress with the treatment with neuroleptics or “magic bullets” of the so called mentally ill. Thus, those quotes are used by Bob to make his points about the bad treatment of those stigmatized as mentally ill and certainly not to condone it. It appears Bob had a pretty close relationship with Dr. Loren Mosher with videos of their talking together about the “mental health system” on the web including a great site called Yoism.

I’m glad and impressed that Dr. Sandy Steingard read Bob Whitaker’s book with an open mind and has gradually been changing her own views based on his work and her own related research and trials while being more upfront with her patients with informed consent while trying to wean people off toxic neuroleptics as much as possible. (I hope you hear me Sandy).

Report comment

Sandy,

My last paragraph expressing my gratitude and admiration for you(despite our differences past and present we’ve agreed could exist while having some meeting of minds) was buried in my post, so I’m recopying it in the hopes you will see it and hang in there. I’m glad to see you still posting at MIA and I appreciate your long term efforts to learn about and fight against the worst of the Big Pharma/biopsychiatry APA/KOL/government industrial complex as you continue to share this process with us.

I now have a famous Dr. Steingard quote I use when I don’t think things easily fall into black and white categories: “I’m feeling “muddled” about this…though that wasn’t your exact quote I’m sure, but the idea sure works when one is honestly “muddled” when trying to make sense of the best choices in very complex, difficult situations that you obviously face daily with limited funds, resources and support.

Here’s my last paragraph in my above post that is a tribute to you though you might not think so reading the rest of my post:

“I’m glad and impressed that Dr. Sandy Steingard read Bob Whitaker’s book with an open mind and has gradually been changing her own views based on his work and her own related research and trials while being more upfront with her patients with informed consent while trying to wean people off toxic neuroleptics as much as possible. (I hope you hear me Sandy).”

I also miss your posts on 1boringoldman and hope you won’t allow the bullies to drive you away as others there expressed as well.

Report comment

Donna,

I’m always blown away by your research, thank you so much for it, and all your references. It’s always so commensurate with my personal experience and research, as one wrongly defamed with today’s “bipolar fraud,” for unethical reasons.

“You cited the quotes by Robert Whitaker as puzzling, but these are actually quotes by the perpetrators quoted by Whitaker in his great book, Mad in America, when Bob first came to realize these sordid truths about the great claims of progress with the treatment with neuroleptics or “magic bullets” of the so called mentally ill. Thus, those quotes are used by Bob to make his points about the bad treatment of those stigmatized as mentally ill and certainly not to condone it. It appears Bob had a pretty close relationship with Dr. Loren Mosher with videos of their talking together about the “mental health system” on the web including a great site called Yoism.”

I ran into information on the web claiming these were Bob’s personal quotes, which struck me as odd, since I’d read both Mad In America and Anatomy of an Epidemic, and had not recalled these as quotes by him personally. Thanks for the clarification.

I too am grateful for the critical psychiatrists like Sandy. But I’m still amazed by the staggering brainwashing of the psychiatric industry, who don’t seem to understand that treating all others, as one would personally would like to be treated, is how all humans should treat all other humans.

And Sandy, I’ve met you in real life, I know your psychiatric training / brainwashing is still difficult for you to overcome. We have a long way to go in regards to retraining the psychiatric industry that the way to help others heal is to actually listen to their concerns and properly deal with their real life problems, rather than just defaming people with scientifically invalid disorders, and tranquilizing people.

Report comment

Donna;

I’m glad you brought up the point of how Robert Whitaker was influenced by David Oaks. One of David Oak’s gifts to this movement is his ability to talk to people and make friends on both sides of this important debate. Many of us who have a loved one who has been/is beinbg harmed by psychiatry experience great difficulty communicating calmly and rationally with people who advocate for coercive practices such as AOT. If psychiatric survivors like David Oaks, were not willing to share their experiences, calmly and with great dignity, to mainstream individuals who ‘had no idea’ what it feels like to be medically raped, things would be even worse than they are currently.

Report comment

Donna and madmom and others-

Thank you all for the interesting discussion. I realize I do not comment to everyone but at least people can know I am reading and when I think I have something of value to say, I say it. It was suggested above that I ignore the negative comments and while an analysis of my comment frequency may suggest this is true, from my perspective, I am respecting the right to voice dissent while avoiding what seem like irreconcilable differences (for instance, that at this point I do not know how to avoid forcing some people into hospitals).

It is interesting to me that David Oaks and I graduated in the same year from the same university. We did not know each other and we only met once at a rally at an APA meeting in 2012. From what I know of him and have learned since, I agree with what madmom has written. Of the many people from our graduating class who have gone on to have prominent careers in medicine – and many are psychiatrists – I think David Oak’s contribution’s are the most significant. I have enormous respect for him and I regret that our paths did not cross sooner.

Report comment

“for instance, that at this point I do not know how to avoid forcing some people into hospitals”

That is quite simple: don’t do it. You may not be able to prevent these people being tortured but others but you’re responsible for your own actions.

Report comment

Sandra, I want to thank you for sharing your insights and perspective on this troubling article in JAMA, the issue of promoting bringing back the “Asylums” for the supposed rising numbers of people in jails and prisons that have mental health labels. This is such a complex issue and so easy to jump to conclusions..As the blogger, “1 boring old man” brings to light that this so called conclusion may in fact not be based on accurate data. I also want to honor you for your openness in sharing your challenges and vulnerability in your personal struggle as you work to find and practice as best you can in a complex world with varying opinions. We need thoughtful doctors like you working in mainstream, ones who are open to new information, that can acknowledge maybe we’re doing things wrong and causing harm. Doctors who listen to what their patients say and are committed to really listening and working with rather than being “the expert”. Acknowledging that psychiatry is in fact not a science but could be an art form, might be the first step. I hope we all can be open to change and remain open to new information and evolve as we learn. What really strikes me is the almost knee jerk response by these members of U.Penn Medical Ethics to jump to this conclusion without an in-depth study of the prison data. (read 1 boring old man’s data that he sights!) And to think the solution is to return to the old State Hospital model (Asylums in this JAMA article) as if that was when things were better! Wow!

This lacks so much of what has been learned over the years post deinstitutionalization. Sadly community models were never funded, which was the supposed grand plan to be the next step when the State hospitals were closed. We certainly know that what helps is human connection, safe places where one can be allowed to go through difficult times without judgment, forced meds, but to have a place to sleep, food and people to talk with or not. A true Asylum in the words of R.D.Laing, not what these “ethicists” are calling Asylum. We know that being with others who have had similar experiences, models such as Peer Respite houses are reportedly benefiting those who have the option to access these homes, again, there are only a handful in the country due to lack of funding. While our federal government, representatives like Tom Insel director of the National Institute for Mental Health, has spoken out against the DSM and has acknowledged the medications don’t “cure” people, and in fact have been causing more harm, what has he directed new federal dollars to do? More Brain Disease research! Zero dollars are being allocated to community support services, true community support. The models are out there, Soteria, Open Dialogue, peer support, Hearing voices support groups, Emotional CPR, Housing First, .. So while we have many alternative models, they are all sorely lacking the necessary funding to be fully staffed and implemented nation wide. Small pockets of alternative models stand out with either private funding (so only the wealthy can access) or short lived pilot projects funded with grants that aren’t able to be sustained because there’s no federal or state money. I think we need to demand that our federal and state dollars be spent on what people who have survived the broken system are telling us… what they say worked for them and replicate more of that. I’m appreciative of having doctors like Sandra Steingard be willing to join with the alternative movement and take risks and speak up. I can imagine how difficult this is as one becomes marginalized by their peers and then often marginalized by the group they are agreeing with and joining. How can we be more welcoming?

.

As more and more doctors and providers of the mainstream system come out and speak up as Sandra is doing, we need to welcome and work together as allies rather than attack and critique. Where is the common ground? How can we build upon this and create a huge ground swell of both outrage at the “business as usual” and demand that funding is targeted to building natural communtiy support on all levels. This includes law enforcement, families as well as professionals, and peer supporters.

Report comment

Beautifully said! Dr. Steingard has already done so much to help give credibility to alternative approaches and we need to all work together for changes to community support. I wonder how this can best be organized?

Report comment

We have a national and international Foundation that was inspired by Whitaker s book, Anatomy of an Epidemic. A group of people with lived experience, researchers, doctors, providers, philanthropists all got together and started this Foundation almost 4 years ago. We have launched some important research (without big pharma $$) that has been published in JAMA, and have both educational funds like the new one with Mad in America (MIACE) on line CEU’s for all providers and family members…as well as Funds to support alternative models of treatment, Open Dialogue and residential models, the Hearing Voices Network, Intentional Peer Support….see our website and please please spread the word for more donors to work with us. Anything is possible. Given that the Federal Government is putting all their tax dollars into brain research, we can’t wait another 50 years for them to find or not find answers, we are trying to be a place where people can both design new funds for starting programs and/or donate to existing alternatives that we know work. Everyone should know about the Foundation and spread the word. http://www.mentalhealthexcellence.com. or contact me if you’d like to learn more. I’m the Senior Program Officer for the Foundation. [email protected]

Report comment

Thanks for making me aware of this. I will be sure to spread the word.

Report comment

The mentally ill are in prison in high numbers also because the USA is the worlds largest police state.