Researchers have identified that antidepressants do not perform much better than placebo pills in a randomized controlled trial (RCT), and that the small difference between antidepressant and placebo efficacy is clinically insignificant (Kirsch, 2010; Moncrieff, J., & Kirsch, 2015; Schultz, 2015; Spielmans, 2015).

Further, even the small difference between antidepressant and placebo efficacy could be the result of an enhanced placebo effect caused by antidepressant side effects. That is, study participants entering a RCT are told they will receive either an antidepressant or a placebo. They are told that the antidepressant they may receive often produces side effects such as dry mouth, upset stomach, etc. Kirsch (2010) illustrated the importance of side effects in the following passage:

Now if I were a patient in one of these trials, I would wonder to which condition I had been assigned. Had I been put in the active-drug group or in the placebo group? Hmm. My mouth is getting dry, and I’m beginning to feel a little nauseous. Normally, I might feel distressed by these symptoms, but I have been informed that these are side effects of the active drug. So instead of feeling distressed, I am elated. My dry mouth and nauseous stomach tell me that I have been given the active drug, rather than placebo. I’m starting to feel better already. (p. 15)

When individuals are able to identify which group they belong to in a RCT, they are said to “break blind”. This is important because RCTs are blinded precisely to minimize the effects of participants’ expectancies, which can distort the measurement of drug efficacy. The largest study investigating how often participants break blind in an antidepressant RCT identified that 78% of participants were able to accurately identify the group they’d been assigned to (Rabkin et al., 1986).

The prevalence of participants breaking blind also suggests that the tiny difference between antidepressant and placebo efficacy is due to participants’ enhanced expectancies. This possibility has been studied. For instance, researchers conducted a study in which side effects were controlled for in the measurement of participant improvement. They found that when side effects are controlled for, there is no statistically significant difference between drug and placebo (Barbui, Cipriani, and Kirsch, 2009). Along similar lines, most studies in which antidepressants are compared to active placebos (placebos that have similar side effects to antidepressants but are not antidepressants themselves) are unable to identify a statistically significant difference in participants’ improvement (Moncrieff, Wessely, & Hardy, 2004). Deacon and Spielmans (in press) suggested that more recent research is not conducted on the scant difference between antidepressant and active placebos because such research would “lack appeal for commercial purposes” (p. 6).

On top of all of this, comparator trials – which are used to compare the effects of different antidepressants to one another, and do not include a placebo group – have significantly larger rates of participant improvement compared to placebo controlled trials (Sneed et al., 2008). In other words, those receiving, for instance, citalopram in a comparator trial improve significantly more than those receiving citalopram in a placebo-controlled trial. This suggests that participant confidence that they are receiving an active medication plays a significant role in clinical improvement they are likely to experience.

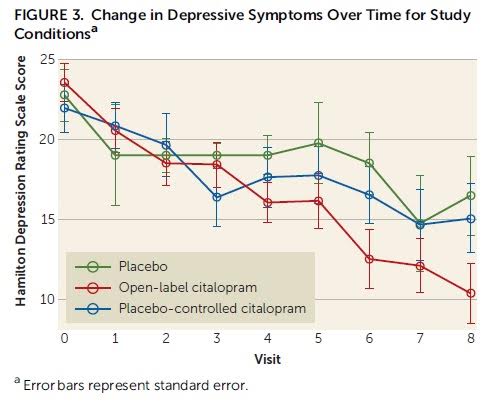

This idea – that participants’ expectation of receiving medication can influence medication efficacy – has been substantiated by a new study. Rutherford et al. (2016), which builds on a previously conducted pilot study, compared the rates of participant improvement in an open group – where participants knew they were certain to receive citalopram (an antidepressant) – and a placebo-controlled group, where participants knew they had a 50% chance of receiving either citalopram or placebo.

Depression severity was measured via the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) and participant improvement expectancy was measured with a modified version of the Treatment Credibility and Expectancy Scale. Importantly, participant expectation for improvement was measured at both pre-randomization and post-randomization. At pre-randomization, the participants did not know to which group they’d be assigned. At post-randomization, clients were informed of which group they’d been assigned and the probability of being administered a placebo (0% probability in the open group and 50% probability in the placebo-controlled group). Although participants were informed of their group, the assessors in the study were blinded to participant group status.

The authors hypothesized that those receiving citalopram in the open group would have a greater expectancy of improvement, and would improve more than those receiving citalopram in the placebo-controlled group. Their hypothesis was supported by the data. Participants in the open group had significantly higher expectation of improvement and significantly greater clinical improvement than participants in the placebo-controlled group. The difference in clinical improvement was partially mediated by the divergent expectancy rates.

A passage from the authors’ discussion summarizes the findings nicely:

“Strikingly, despite receiving the identical antidepressant medication, being treated by the same study clinicians, and visiting the same treatment site, depressed subjects who knew they were receiving citalopram improved on average 6 HAM-D points more than those receiving citalopram who were aware they had a chance of receiving placebo.” (p. 6)

This study reinforces a large body of evidence suggesting that an individual’s expectancies for improvement significantly contribute to their actual improvement (Constantino, 2012; Kirsch, 2016). The importance of expectancies is worth paying attention to now as more clients, clinicians, and researchers are endorsing a reductionist view of psychological disorders – i.e., that psychological disorders are fundamentally brain disorders (Hunter & Schultz, 2016; Schultz, 2015). This perspective has been shown to increase prognostic pessimism (i.e., decrease improvement expectancy) and increase reliance on what are often harmful medications (Andrews, Thomson Jr, Amstadter, & Neale, 2012; Carvalho, Sharma, Brunoni, Vieta, & Fava, 2016; Haslam & Kvaale, 2015; Lebowitz, 2014).

It’s worth noting that Rutherford et al. (2016) was a small study and that replication, especially with a greater number of participants, would be worthwhile. Nevertheless, given the significant evidence congruent with Rutherford et al. (e.g., Barbui, Cipriani, and Kirsch, 2009; Moncrieff, Wessely, & Hardy, 2004; Sneed et al., 2008; Kirsch, 2016), it wouldn’t be surprising if future research finds similar results.

References:

Andrews, P. W., Thomson Jr, J. A., Amstadter, A., & Neale, M. C. (2012). Primum non nocere: an evolutionary analysis of whether antidepressants do more harm than good. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 117.

Barbui, C., Cipriani, A., and Kirsch, I. (2009). Is the Paroxetine-placebo efficacy separation mediated by adverse events? A systematic re-examination of randomized double-blind studies. Submitted for publication, 2009.

Carvalho, A. F., Sharma, M. S., Brunoni, A. R., Vieta, E., & Fava, G. A. (2016). The safety, tolerability and risks associated with the use of newer generation antidepressant drugs: A critical review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 85(5), 270-288.

Constantino, M. J. (2012). Believing is seeing: An evolving research program on patients’ psychotherapy expectations. Psychotherapy Research, 22(2), 127-138.

Deacon, B. J. & Spielmans, G.I. (in press). Is the efficacy of “antidepressant” medications overrated? In Lilienfeld, SO, & Waldman, ID (Eds.), Psychological science under scrutiny: Recent challenges and proposed remedies. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Haslam, N., & Kvaale, E. P. (2015). Biogenetic explanations of mental disorder The mixed-blessings model. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(5), 399-404.

Hunter, N., & Schultz, W. (2016). White Paper: Brain scan research. Ethical Human Psychology and Psychiatry, 18(1), 9-19.

Kirsch, I. (2010). The emperor’s new drugs: Exploding the antidepressant myth. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Kirsch, I. (2016). Response Expectancy. In S. Trusz P. Babel (Eds.), Interpersonal and intrapersonal expectancies (pp. 25-34). New York, NY: Routledge.

Lebowitz, M. S. (2014). Biological conceptualizations of mental disorders among affected individuals: A review of correlates and consequences. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 21(1), 67-83.

Moncrieff, J., & Kirsch, I. (2015). Empirically derived criteria cast doubt on the clinical significance of antidepressant-placebo differences. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 43, 60-62.

Moncrieff, J., Wessely, S., Hardy, R (2004). Active placebos versus antidepressants for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1, 1-27.

Rabkin, J. G., Markowitz, J. S., Stewart, J., McGrath, P., Harrison, W., Quitkin, F. M., & Klein, D. F. (1986). How blind is blind? Assessment of patient and doctor medication guesses in a placebo-controlled trial of imipramine and phenelzine. Psychiatry research, 19(1), 75-86.

Rutherford, B. R., Wall, M. M., Brown, P. J., Choo, T. H., Wager, T. D., Peterson, B. S., … & Roose, S. P. (2016). Patient expectancy as a mediator of placebo effects in antidepressant clinical trials. American Journal of Psychiatry, OnlineFirst, appi-ajp.

Schultz, W. (2015). The chemical imbalance hypothesis: an evaluation of the evidence. Ethical Human Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(1), 60-75.

Schultz, W. (2015). Neuroessentialism Theoretical and Clinical Considerations. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, OnlineFirst, doi: 10.1177/0022167815617296

Sneed, J. R., Rutherford, B. R., Rindskopf, D., Lane, D. T., Sackeim, H. A., & Roose, S. P. (2008). Design makes a difference: a meta-analysis of antidepressant response rates in placebo-controlled versus comparator trials in late-life depression. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(1), 65-73.

Spielmans, G. (2015). When marketing met science: Evidence regarding modern antidepressants and antipsychotic medications. The Behavior Therapist, 38(7), 199-205.

Well stated, William!

I took antidepressants for a while about 30 years ago and they made no difference to my mood whatsoever. But I wasn’t clinically depressed at the time, I was more miserable after coming off stronger psychiatric drugs.

But over the years my happiness levels have definitely improved and this is because of regular Buddhist breathing meditation. This practise has worked for me and has also I believe, been clinically proven to increase all around happiness levels.

Report comment

I remember as well years ago attending a Buddhist Centre and a lady was talking to the monk about taking antidepressants.

The monk advised her to meditate regularly and to come off the medication slowly. At the time I thought that he shouldn’t be giving this advice. But, I realise now that he was right and that his advice was as well founded as if the lady was using any other harmful substance.

Report comment

This whole subject is fascinating. To think a multi-billion dollar market might be built on the placebo effect.

In considering possible causes of depression, a biological basis is one possibility and I think we need to also consider the possibility that depression could be a symptom of more than one biological cause. This means that ADs could, in some case, improve depression, while in other cases make it worse, yet you would still get the overall results shown in all these fascinating placebo studies. This is what William Walsh seems to have found in his decades of nutrient treatment of depression. I think his epigenetic approach is much more scientifically grounded and incredibly more sensible than the *very profitable* and poisonous approach the drug companies push. I don’t think I’ve ever seen him address the placebo effect in his work, but surely it is at work there too.

Report comment

“Researchers have identified that antidepressants do not perform much better than placebo pills in a randomized controlled trial ”

Okay, I appreciate that people are trying to stop the use of psychiatric medications. But why does the above even matter? Why is anyone taking psychiatric medications in the first place? To me, those meds should just be flushed down the toilet. No further discussion needed.

Is it because people are duped? Is it because people use them like they use alcohol and street drugs?

People feel psychological distress because they live with a compromised social identity, so they are taken advantage of. They live being subject to prejudice and abuse.

And then so long as they seek Psychiatry, Psychotherapy, and Recovery as the remedy, they only make the situation worse.

The real remedy, as it always will be in a civilized society, is in taking legal and political action.

But the mental health and recovery systems instead try to talk you down and make you believe that the problem lies between your own two ears. So the first step is to reject mental health and recovery approaches.

Easier to talk here, please join:

http://freedomtoexpress.freeforums.org/why-does-anyone-use-psych-meds-t343.html

Nomadic

Report comment

I absolutely agree, the “bio-bio-bio” 15 minute med-check reductionist approach to psychiatry did result in my psychiatrist’s opinions becoming “irrelevant to reality” to me quite quickly. And I will say my psychiatrist was terrified in the end, when I confronted him with all his delusions about me written into his medical records. He had delusions of grandeur I would believe my entire life was “a credible fictional story.” Never judge a book by it’s cover, the psychiatrists judge people like that.

Report comment

Can there be hope on the horizon?

I wrote elsewhere on this publication about my hope with Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation.

It was given the FDA approval in 2008 and a quick Google search of the subject will give you several places to start research. I just found this Dr. out of Indiana who has done a you tube video that I thought was very helpful.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0QwCuglKjME

http://cadywellness.com/

Report comment

William, you write, “Depression severity was measured via the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) and participant improvement expectancy was measured with a modified version of the Treatment Credibility and Expectancy Scale.”

And so this Hamilton Rating Scale is:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamilton_Rating_Scale_for_Depression

“used to rate the severity of their depression by probing mood, feelings of guilt, suicide ideation, insomnia, agitation or retardation, anxiety, weight loss, and somatic symptoms.”

Why would anyone ever submit to this, with or without drugs?

Can’t you see that it is completely abusive and immoral to try and measure people this way, or to expect them to comply?

And how could you ever see lowering people’s anger and distress, as it is always about injustice, as something to be desired?

Nomadic

Report comment