A recent study, published in Current Directions in Psychological Science, used statistical methods to determine if men and women actually fall into two distinct neurobiological classes. Their results supported the opposite view: male and female traits exist on a continuum, and no clear two-class structure could be found.

Reis and Carothers, the authors of the study, write that “although there are average differences between men and women, these differences do not support the idea that ‘men are like this, women are like that.’”

In fact, according to the authors, “sex differences are better understood as individual differences that vary in magnitude from one attribute to another rather than as a suite of common differences that follow from a person’s sex.” Simply put, each person has a set of traits which all fall on a continuum of gendered interpretation, and each trait is independent of the others. That is, knowing that a person has a stereotypically masculine trait in one area does not mean that the person will have other stereotypically masculine traits.

According to popular opinion, the brains of men and women are biologically different. After all, “men are from Mars, women are from Venus.” For more than a century, the scientific establishment has purported to confirm this popular opinion via biological explanations. For instance, a Victorian finding that women’s brains were smaller was often cited as indicating male superiority—despite the fact that women’s brains are proportional to their body mass.

According to popular opinion, the brains of men and women are biologically different. After all, “men are from Mars, women are from Venus.” For more than a century, the scientific establishment has purported to confirm this popular opinion via biological explanations. For instance, a Victorian finding that women’s brains were smaller was often cited as indicating male superiority—despite the fact that women’s brains are proportional to their body mass.

Reis and Carothers caution that neuroscientific results that class humans into two categories, “male” and “female,” tend to reify gender stereotypes by giving them the appearance of objective scientific truth.

Cordelia Fine, Senior Research Fellow at the Department of Psychological Sciences at the University of Melbourne, Australia, has extensively studied neurosexism, or the use of neuroscientific results to justify stereotypical assumptions about gender differences by relating them to “natural” or “biological” differences. In her 2010 book Delusions of Gender, and in a 2013 article published in Neuroethics, she conducted a systematic review of studies involving neurological gender differences.

According to Fine, studies of neurological gender differences fall prey to many errors. She writes that consistently, neuroscientific researchers that make claims about gender tend to overinflate the results with false positives, in which researchers find correlations that are not truly there. Additionally, she writes, researchers interpreting study results tend work backward, starting with stereotypical assumptions and attempting to justify them with flimsy neurological data.

Fine makes clear, as do others who study the neuroscience of gender, that the influence of the environment is integral to understanding the biology of gender. That is, the ways in which boys and girls are socialized has an impact on their brain development. The science of epigenetics focuses on the ways in which the environment impacts gene expression—activating and deactivating genes, and determining how cells express genetic orders. Studies that focus on neurophysiological differences as innate differences miss the vital impact of the environment and socialization on the brain.

Donna Maney is an expert in neurobiology at Emory University. Earlier this year, she published an article stating that “the communication and public discussion of new findings [in the neuroscience of gender] is particularly vulnerable to logical leaps and pseudoscience.” She cautions that researchers should resist speculating about “functional or evolutionary explanations for sex-based variation, which usually invoke logical fallacies and perpetuate sex stereotypes.”

A recent study by O’Connor and Joffe at University College, London confirms this result. The authors found evidence that “traditional gender stereotypes were projected onto the novel scientific information” leading to “benevolent sexism, in which praise of women’s social-emotional skills compensated for their relegation from more esteemed trait-domains, such as rationality and productivity.” O’Connor and Joffe state that of the numerous potential interpretations of the results of neuroscience studies, researchers tended to choose the interpretation most consistent with their assumptions and stereotypes about gender.

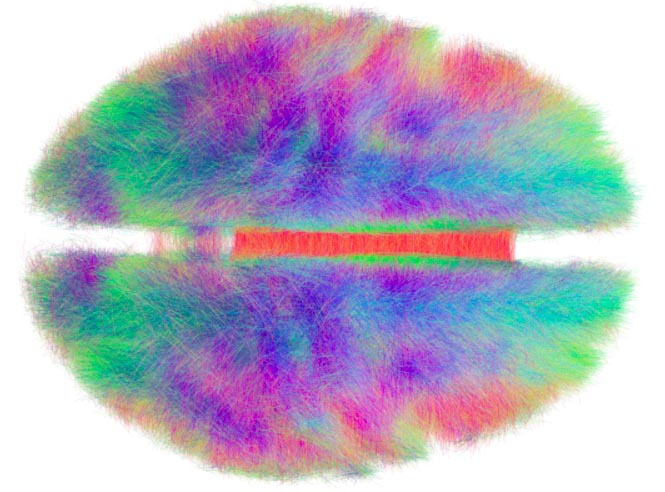

Additionally, researchers have found that within-group (different women, for instance) biological differences are just as profound as between-group (women vs. men) biological differences. Thus, researchers have argued for an understanding of a “human brain mosaic” in which each individual brain has a number of traits that may be similar to others of the same gender, or different. In fact, a recent article in Human Neuroscience finds that essentialist notions of gender are inherently flawed predominantly because they rely on overly simplified understandings of neuroscientific results that do not take into account the inconsistency of actual gender neuroscience findings.

These researchers suggest that we need to be cautious about gender biases when interpreting neuroscientific data, lest we fall into the trap of confirming stereotypes with insubstantial findings and reifying sexism by giving it the veneer of science.

****

Reis, H. T., & Carothers, B. J. (2014). Black and white or shades of gray: Are gender differences categorical or dimensional? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(1), 19-26. (Abstract)

Testosterone dramatically changes the brain. To deny males have testosterone is insane. The rate of age of onset of “schizophrenia” and the increase of testosterone as a male matures seem to correspond and NO ONE TALKS ABOUT.

Testosterone in men http://www.mhhe.com/socscience/sex/common/ibank/ibank/0088.jpg

Age of onset http://www.schizophrenia.com/photos/szage.onset.gif

Anger coming from the increase in hormones is renamed “psychosis” by legal drug pushers, and the psychiatric drugs do solve the immediate problem of the animal-who-is-not-following-orders.

Report comment

“The Contest” :

Insomnia and anger from lack of sex

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Contest

“The Contest” was the 51st episode of the NBC sitcom, Seinfeld. The eleventh episode of the fourth season, it aired on November 18, 1992.[1] In the episode, George Costanza tells Jerry Seinfeld, Elaine Benes and Cosmo Kramer that his mother caught him unaware while he was masturbating. The conversation results in George, Jerry, Elaine and Kramer entering into a contest to determine who can go for the longest period of time without masturbating.

….

The contest affects their sleep, and the remaining contestants suffer insomnia, while only the people who were eliminated can sleep peacefully.

(Jerry and George. They’re bickering at each other due to the lack of sex)

GEORGE: All you got is instant coffee? Why don’t you get some real coffee?

JERRY: I don’t keep real coffee in here, I get my coffee on the outside! (Intercom buzzes. He answers it) Yeah?!

ELAINE: (Through intercom) It’s Elaine.

JERRY: (Shouting) Come on up! (Opens his door for Elaine)

GEORGE: Where did you get those socks?

JERRY: I don’t know.

GEORGE: I think those are my socks!

JERRY: How are these your socks?!

GEORGE: I don’t know, but those are my socks! I had a pair just like that with the blue stripe, and now I don’t have them anymore!

JERRY: (Sarcastic) Oh, yeah, that’s right, well, you fell asleep one day on the sofa and I took them off your stinkin’ feet. They looked so good to me, I just had to have them!

GEORGE: Yeah, well, they’re my socks!

JERRY: They’re my socks!

(A brief moment passes as they look at each other)

GEORGE: Oh boy..

JERRY: What are we doing here..

GEORGE: ..Oh boy.

JERRY: This is ridiculous.

GEORGE: Do you believe this? We’re fighting. We’re fighting.

JERRY: I haven’t been myself lately. I’ve been snapping at everybody.

GEORGE: Me too. I’ve been yelling at strangers on the street.

Report comment

Why are you citing popular culture when the popular culture is the very thing constantly shamefully perpetuating its own nonsensical stereotypes? Why are you blathering on about testosterone and its unfounded mythological ‘poisoning’ effects with no real in-depth knowledge of the subject? Congrats on being propagandized, brainwashed and offensively insensate, you’ll fit in nicely with the rest of the sheeple.

Report comment

I found a neurologist to be the biggest misogynist I’d ever met, so would say there is absolutely a problem within the psychiatric/neurologist industries of gender bias. According to my neurologist’s medical records, he claimed me to be “w/o work, content, and talent,” prior to ever looking at my work, and because he had a “not believed by doctor” problem, he didn’t believe I was co-chairing an organization with 250+ volunteers, even though I did that the majority of the time I was seeing him. I had no idea he was so disrespectful and delusional, however, until I read his medical records.

But after finally taking the time to look at my work, my neurologist did state it was “work of smart female” and “insightful.” Although, when I later confronted him with the fact his medical records were filled with his incorrect beliefs of where I grew up, what universities I graduated from, and the fact the medical evidence of the abuse of my child was also handed over, my neurologist quickly turned into a dangerous paranoid who wanted my child drugged and wanted to redrug me. He even declared my entire real life to be a “credible fictional story” in his medical records. Of course, when one realizes how incredibly stupid and ungodly unethical such a neurologist is, one does run away from such a paranoid psychopath as quickly as possible.

It’s really a shame the psychiatric/neurological industries are filled with people who are not intelligent enough to actually listen to what a person says, and believe what the person says. And they harbor odd delusions that those who utilize both sides of their brain are less insightful than those in the psychiatric industry who believe “chemical imbalances in brains” are caused by genetics, rather than by psychiatric drugs, in other words iatrogenesis, in my case anticholinergic toxidrome poisoning. It’s sad how deluded today’s psychiatric industry is, and it’s even sadder that they are continuing to harm and torture millions of innocent children, for profit.

Report comment

I am sorry you went through that, so incredibly abusive, and I went through similar. I am female, and was basically painted as hysterical, sexual damages caused by drugs not taken seriously because female sexuality unimportant and I’m too emotional and irrational to understand what is happening my own body right?!?!?? Definitely had my health and reality “mansplained” to me so many times. Psychiatry is openly contempt-filled towards females. Female bodies are getting toxic chemicals dumped into them, psych drugs and birth control, all kinds of stuff, at record rates. No respect for sacred femininity.

Report comment

A lot of MIA is about pushing back against the pseudoscience, omissions, and obfuscation of pharma and psychiatry. This appears to be another area where there’s pseudoscience, omissions, and obfuscation by people based on making a world the way they want it for their own ends. This is dangerous.

I’m not a biologist (neither is the author or the overwhelming majority of people with these views, or any of the people cited in the post), but my understanding of this issue is that it has become a war between ‘social justice warriors’ of academia and irrefutable facts of human biology. The biologists speak to the facts that there are massive differences between men and women (and they are especially emerging where the playing field is deliberately leveled, like in Sweden), while the ‘social justice warriors’ speak to what appears to be wishful thinking and statistical game-playing (ironically, like the type we see in pharma studies…).

I spent a part of my life in the ‘social justice’ camp and I recognize the anger of the people within that camp. But wishing that gender differences don’t exist doesn’t make it so. The facts of biology, and the facts of our planet, say something else entirely. (And @markps2 makes good points in the first comment.)

Wishing on the basis of ideology has led to legislating ‘thought crimes’ and ‘speech crimes’ to that end (apparently passed in New York State and in some Canadian provinces), and will not have the sunny outcome the ‘social justice warriors’ imagine. When facts are quashed in favour of ideology you get the Soviet Gulag, Mao’s China, and Pol Pot’s Cambodia. Remember how the Soviets utilized psychiatry? MIA readers beware. A better idea is to look carefully at the real science, accept its facts, and act accordingly.

Liz Sydney

Report comment

I guess I read this article differently. I think what it says is that while there are differences between males and females, they are AVERAGE differences and can’t be generalized to all members of either gender. I think it also says that researchers are biased in their interpretation of data based on their own cultural stereotypes. I don’t think it’s possible to deny the huge impact of large amounts of testosterone on the brain and body – it is, in fact, what makes a body turn out male rather than female. But it’s also very easy to ignore the huge impact of social and cultural training on how men vs. women act in a given culture.

As is frequently the case in the nature vs. nurture argument, it’s not one or the other, but both.

— Steve

Report comment

Here’s an example of some dangerous gender-pronoun-based legislation, based on ‘social justice’ zealousness and not science:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2016/05/17/you-can-be-fined-for-not-calling-people-ze-or-hir-if-thats-the-pronoun-they-demand-that-you-use/

Liz Sydney

Report comment

I think that law is probably an effort to prevent discrimination, which is very real. Why can’t we call people by whatever pronouns they prefer? Why do each of us have to be the gender police for everyone else?

Report comment

Language is a set of standardized rules to allow interpersonal communication. I’m not going to speak a different language just to accommodate your whims.

Report comment

Languages are mutable, and it costs you nothing to treat other people with respect and courtesy. I don’t even personally care for neo-pronouns, but if a person wants to be called that way, I’ll make an effort to do that.

By the way, I’m pretty sure that the whole point of neo-pronouns such as ‘ze,’ ‘hir,’ etc., is to create a grammatically correct option for gender neutral, as opposed to ‘they/them/their,’ which are commonly used for gender neutral, but are plural and therefore grammatically incorrect. You can like alternate pronouns or dislike them, but there isn’t anything whimsical about them.

Report comment

I have no trouble believing that there is bias in the science. This article was biased, too, though.

There are too many conclusory statements for this to be convincing. A conclusory statement ‘… is a statement made in an argument that states a conclusion, without any foundation, underlying logic, or reasoning.” So, something like this…

“Donna Maney is an expert in neurobiology at Emory University.”

Says who?

“Earlier this year, she published an article stating that “the communication and public discussion of new findings [in the neuroscience of gender] is particularly vulnerable to logical leaps and pseudoscience.”

That’s nice, but it’s just what someone said. Examples of studies that relied on logical leaps and pseudoscience, and the mechanisms and effects of bias, are needed.

.

Report comment

Just because brain based gender differences are indeed on a spectrum does not mean that brain based gender differences do not suddenly exist and as a result no longer influence behavior.

People arguing the environmental influences of gender development are also not without bias. There is a ton of controversy surrounding Zucker and his research on gender dysphoria persistance. His research has been highly biased and he argues that most children eventually grow out of gender dysphoria(just a phase) which has been used by people in support of conversion therapy for transgender persons. One particular damning criticism of his research on gender dysphoria persistence in FTM persons is that if the person was unsure of wanting to have masculinzing surgery yet they considered themselves to male and wanted to be perceived as male they were NOT counted has having persistent gender dysphoria. Basically Zucker used biased operational definitions in order to produce the results he desired. According to Zuckers definition my ex boyfriend a FTM person would have not even counted as having gender dysphoria. Yet certain conservative groups continue to use his research statistics to justify arguments for torturing children in the form of conversion “therapy”. Google “leelah alcorn” if you would like to read about the harms of such an approach.

This area of research is very relevant to transgender individuals in that numerous studies have shown that MTF persons have brain structures more closely resembling those of cisfemale controls and FTM persons have brain structures more closely resembling those of cismale controls. The current theory is that testosterone exposure has a masculinizing/defeminizing effect on the baby while it is developing in the womb and that the brain and genitals are effected by testosterone exposure(or lack of) during different trimesters.

This article summarizes Swaabs research up to 2009 he has also done more research since then. His later research also supports that the masculinizing/defeminizing effecst of prenatal testosterone exposure creates a spectrum of changes in the brain.

Swaab, D. F., & Garcia-Falgueras, A. (2009). Sexual differentiation of the human brain in relation to gender identity and sexual orientation. Functional Neurology, 24(1), 17-28

Report comment

It’s worth noting the similarities between biological psychiatry and transgender ideology: this analysis was written by a friend of mine:

Biopsych: your symptoms are caused by an imbalance of neurotransmitters in your brain (nothing to do with your life experience or how you interpret it).

Trans: your dysphoria is caused by a mismatch between your brain and your body (nothing to do with your life experience or how you interpret it).

Biopsych: your symptoms can and should be treated with drugs which will make them go away.

Trans: your dysphoria can and should be treated with cross-sex hormones which will make it go away.

Biopsych: upon taking your drugs you may (probably will) have a transformative, freeing experience of being able to Function more effectively in a respected social role.

Trans: upon starting hormone treatment you may (probably will) have a transformative, freeing experience of being able to Function more effectively in a respected gender role.

Biopsych: anyone who says or suggests that you should not be taking your drugs is blaming you by using a simplistic “mind over matter” view to label you as morally defective and denying the reality of your brain disease.

Trans: anyone who says or suggests that you should not be undergoing hormone treatment (or otherwise changing your gender performance) is a reactionary bigot with a “mind over matter” view who only sees you as a contemptible sexual deviant and denies the reality of your brain-body mismatch.

Biopsych: if you think you might have Depression/Anxiety/Bipolar/Schizophrenia/some other Disorder then you probably do and should definitely see a professional who is very likely to give you a diagnosis and a prescription.

Trans: if you think you might be trans then you probably are and should definitely see a professional who is very likely to confirm you are trans and give you a hormone prescription.

Biopsych: you will probably need to take your drugs for life in order to manage your symptoms.

Trans: you will, after genital surgery, definitely need to take your hormones for life in order to maintain your gender performance. (And to prevent osteoporosis, etc.)

Biopsych: it is more important to fight the stigma against people who use psychiatric drugs than it is to look for psychosocial/trauma/not-directly-biological causes of their symptoms.

Trans: it is more important to fight the stigma against people who seek medical transition than it is to look for psychosocial/trauma/not-directly-biological causes of their dysphoria.

Report comment

Yes, there are parallels between biopsych’s and some transgender peoples ideals. But it is easy to draw similarities between many things. For instance, I know many women who take bioindentical estrogen as they have had hysterectomies so they no longer produce their own and they just feel better with estrogen than without it. I could compare the similarities of this situation to alcoholics who feel better with alcohol than without, or to anyone who is chemically dependent. In both situations people take substances to feel better but their is radically different stigma levels between these similar situations and I don’t think these women would like their situation being conflated with the alcoholics situation.

Some transgender people do think in similar ways to biopsycs which is not surprising since biopsycs have traditionally been gatekeepers for most of the treatment that transgender people seek. There has been some movement away from gatekeeping but its slow going as doctors are powerful and its hard to get people to give up or share their power. One of the criticisms I actually pointed out in my earlier comment was that Zucker’s research discounted transgender people as not being transgender if they did not want surgery. Transgender people who did not want surgical interventions did not fit Zuckers narrative of what a transgender person should be or want so their experiences were discounted and instead twisted to fit his view and research conclusions. There are lots of reasons that anyone may have for not wanting surgery, this includes transgender people too. Each persons situation is unique and some transgender people definitely do need surgery in order to feel congruent in their body and to resolve their gender dysphoria. One potential reason for not wanting surgery, is that if a person transitions early enough then they may not need surgery in order to blend in as they avoid the damage caused by a incongruent puberty and the resulting secondary sexual characteristics. Another potential reasons is that there are also people who do not identity on a gender binary or are content being more of a hybrid or androgynous in their gender expression or identity. Also, its true that hormones do help a lot of transgender people feel better and biodentical hormones are certainly way more natural and safer than the damaging substances that biopsycs peddle.

Report comment

“Some transgender people do think in similar ways to biopsycs which is not surprising since biopsycs have traditionally been gatekeepers for most of the treatment that transgender people seek.”

Bingo.

Report comment

Also want to put this out there, that in transgender healthcare having a view that is similar to a biopsyc view might not be all bad or incorrect… well in relation to hormones that is.

There is that discredited idea that psyc meds are like insulin for diabetics, which they are not.

However, in transgender hormone care it is known what the average range of testosterone is for cismales and estrogen is for cisfemales. So unlike psyc meds but like insulin and blood sugar monitoring we know the ranges that hormones should typically fall into. Transgender people that choose to pursue hormone therapy generally have their blood taken and their hormone doses adjusted to fall in normal ranges that are typical for the gender in which they identify. Their hormone therapy is also typically prescribed and monitored by GP’s or endocrinologists not psychiatrists.

Report comment

When you’re ideologically trapped, you can’t see how abilities are sometimes complementary, such as alleged male and female differences in spatial abilities. In antiquity, the guys, supposedly better at seeing terrain spatially, are the ones who could find where the mushrooms grew, but they were useless without their womenfolk, who are spatially better at identifying small physical characteristics of objects. Without both types of perception, unable to find the mushrooms, the women would starve, while the men, unable to recognize which mushrooms were edible, would poison themselves.

Report comment

There are many, many problems with personally aggrieved social scientists pretending planet Earth’s biology away in favour of wishful thinking. If only the issue was truly about ‘being nice’ and calling people the names they prefer. But sorry, people, Authoritarian Social Justice Warriors don’t actually want ‘nice’; they demand legislated control over everyone’s speech and actions, which is ‘1984’ and ‘Brave New World’. Legislation already passed (NY State and elsewhere) will end up being challenged up to Supreme Courts, and will end up being proven unconstitutional. Or else we will fall to totalitarianism, which happens with regularity around the world.

This brief Op-Ed in the New York Times today speaks to the large issues involved with North American Liberalism run amok, and speaks to the gender issues raised in this post:

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/20/opinion/sunday/the-end-of-identity-liberalism.html?action=click&pgtype=Homepage&clickSource=story-heading&module=opinion-c-col-right-region®ion=opinion-c-col-right-region&WT.nav=opinion-c-col-right-region&_r=0

The problems with psychiatry and emotional/behavioural/mental health (the focus of MIA, after all) will not in any way be repaired if and when we start pretending away the facts of biological gender differences.

I regret to see MIA publishing this sort of fuzzy, resentful, agenda-filled ideology. I came to MIA for Robert Whitaker’s critical thinking skills, and for MIA’s ability to cut through the fog and excrement and get to the truth. Disappointing.

Liz Sydney

Report comment

An article on the brain.

“The hypothalamus controls some of the basic functions of life including hormonal activity via the pituitary gland. There are several gender differences in the gland present between males and females.”

http://www.news-medical.net/health/Hypothalamus-Males-and-Females.aspx

Report comment

Nope, sexism is not biological. It is an acquired trait instead.

Report comment