A recent study, led by Dr. Andrzej Werbart, interviewed seven psychoanalytic therapists about their experiences in therapy with young adult patients who did not improve. The results, published in Psychotherapy Research, demonstrate that therapists experience a “split picture” of the “nonimproved” patient and, in their confusion, struggle to strike a balance between distance and closeness which results in an overall sense of lost control in the therapy process.

“The more the therapist tried to deepen the relationship to help the patient reach her unformulated experiences, the more the patient withdrew, adding to the therapist’s confusion, therapists reported. Over time, the therapists became frustrated and unable to find a way to move further with their patients, being stuck in a struggle.”

There is extensive evidence suggesting psychotherapy is effective for a wide-range of mental health concerns. Yet, a substantial number of clients do not experience improvement in psychotherapy. Worse still, some experience what is referred to as “deterioration” during treatment, or a worsening of their distress.

While evidence suggests that therapists can improve outcomes by identifying instances of unsuccessful treatment, research also demonstrates that it is difficult for therapists to detect their treatment failures. Werbart and colleagues highlight the importance of understanding the specific factors that lead to treatment improvement, stagnation, or deterioration, thereby justifying the merit of this project examining therapists experiences of “unimproved” psychotherapy cases.

Using quantitative inclusion criteria and qualitative analysis techniques, the researchers pose the following questions in this study:

- “How do therapists describe their work in these particular cases and themselves as the particular patient’s therapist?”

- “How do the therapists describe their patients, the therapeutic relationship, and the therapy outcome?”

- “Which factors and processes seem to have been crucial for the unsuccessful outcome from the view of the therapist?”

They also investigated “if there are any particular characteristics of the therapists’ experiences already observable at the outset of treatment, as reported in baseline interviews.”

Archival data from the Young Adult Psychotherapy Project (YAPP) was used. This study featured naturalistic, longitudinal data of psychoanalytic psychotherapy with young adults (who were mostly self-referred) in Stockholm, Sweden. The patients participated in therapy for a mean of 22.3 months, and outcome data were assessed at termination, at 1.5-years, and at a 3-year follow-up.

The researchers used selection criteria to exclusively study cases of non-improvement, defined as “patients who reported a symptom level in the clinical range at pretreatment, and no reliable symptom reduction or even deterioration at termination.” The cut off between nonimproved and clinically improved cases was guided by the Global Severity Index (GSI) outcome measure. Psychotherapists were recruited from a previous study that examined patients’ perspectives of their nonimproved psychotherapy experience.

In this study, eight patients worked with seven psychotherapists. Four of the seven therapists were female, and three were male. The average age of the therapist sample was 52.9 years.

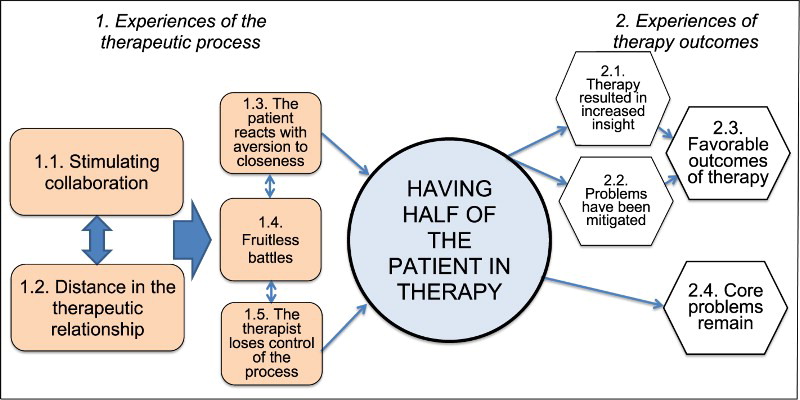

After engaging in semi-structured interviews with therapists and coding therapist accounts through grounded theory, the researchers identified a core category that connected additional subcategories and domains. This core category, titled “Having Half of the Patient in Therapy,” was created based upon direct quotations from the interviewed therapists.

The core category “Having Half of the Patient in Therapy,” captured a process in which the therapist experienced parts of the patient as obscure or absent at the beginning of therapy—that essential parts of their life circumstances or problems were excluded in their presentation. Despite initially feeling drawn into the patient and their story, the therapist felt unable to bridge the distance. This ultimately resulted in a perceived sense of the therapist’s loss of control in the therapy process and an inability to achieve a favorable balance of closeness and distance.

Nine subcategories are mapped around this core category. These nine subcategories were gathered into two thematic domains: 1) Experiences of the therapeutic process and 2) Experiences of therapy outcomes.

Experiences of the therapeutic process

The therapists initially described being interested and involved in work with the patient. They did not struggle to locate empathy for the patient and experienced the patient as extraordinarily verbal, capable, and fond of therapy, despite having a traumatic background. Werbart and co-authors write:

“The therapist experienced herself as unusually alert, free or creative, and could describe a liberating feeling that things will turn out and clear up with time and that they were working successfully. It was easy to like the patient and feel empathy, and the therapist felt important, as the patient dared to open up and show confidence in an unusual way.”

From the beginning, therapists felt a distance from the patient, or from parts of the patient’s problem, that increased over time. Therapists understood the patients as having difficulties with allowing for closeness in their professional relationship and interpersonal relationships outside of therapy. One therapist participant stated: “She has a certain distance; she has a hard time letting her feelings flow and expresses nothing strong about her bond to me either.”

Additionally, they described the patient as exhibiting a growing aversion to closeness, as depicted by this therapist’s statement:

“The more therapy meant to her, and the more I meant to her, the worse, the more dangerous the therapy became for her and the more she needed to turn me into a no-body. During that time I was functioning pretty much as an extension of the furniture in the room, I was part of the fitting-up, so to say, I was not a living person.”

Therapists perceived the patients as becoming increasingly threatened by questions, confrontations, and interventions, resulting in “fruitless battles” and unsuccessful attempts at collaboration. Ultimately, the therapist reports experiencing a loss of control in the process, feeling perplexed, overinvolved, and more apt to forego their professional stance.

Experiences of therapy outcomes

The therapists in the sample described believing that the patient gained increased insight into their life, despite the unimproved outcome of the case. They felt that the patient’s symptoms decreased in strength and that patients acquired new ways to manage their life.

Additionally, they reported some favorable therapy outcomes such as perceiving the patient’s improved trust in the therapeutic relationship as well as a change in interpersonal functioning. However, therapists understood the patient’s core problems to remain at termination, and that the perceived improvements had not led to substantial change.

“The right side of Figure 1 represents therapy outcomes, as generally described by the therapists at termination. Therapy resulted in increased insight and Mitigated problems, thus leading the therapists to conclude that the therapy had Favorable outcomes. At the same time, all therapists concluded that the patient’s Core problems remain. There is a remarkable lack of any connection or interaction between these irreconcilable outcome subcategories.”

These results were interpreted by the researchers alongside the results of their sister study, wherein they examined patient perspectives of unimproved psychotherapy, captured by the title “Spinning One’s Wheels.” While patients experienced a too passive therapist, therapists described a half-present patient.

“Thus, there is a marked difference between the patients’ and the therapists’ experiences of the therapeutic process in cases of nonimprovement. We interpreted experiences of nonimproved patients as an unbalanced therapeutic alliance, with a good-enough emotional bond, but not enough agreement concerning therapy goals and tasks,” the researchers write.

Werbart and colleagues continue to describe that the patients were likely to have experienced difficulty approaching and bringing up emotionally laden subjects, and, in the end, therapists were unable to help them manage this. In this way, the researchers discuss how therapists may have overestimated the patient’s functioning while underestimating the scope of the patient’s problems.

“Both patient and therapist described from their different viewpoints that the therapist did not understand the patient, which might have added to the patient’s experience of an artificial relationship.”

Further, the therapist struggled to adapt their approach to the patient’s tailored needs and level of functioning, despite their active attempts to meta-communicate, perhaps as a result of their overestimating the patient’s functioning. Therapists, convinced they needed only more time, or more work, but were generally on the right track, may not have considered adopting a new understanding or focus.

Werbart and coauthors explain how this false conviction leads therapists to potentially interpret unsuccessful therapy as patient resistance:

“They do not attribute the limited progress in therapy to their own limited understanding of the patient’s problems, but rather to the patient’s lack of will to open up and try harder. Taken together, this resulted in an inability to adapt their technique and to address their interventions to the patients’ core problems.”

While the patient described their interest and involvement in the case, this may have compromised their ability to maintain an effective balance of closeness and distance successfully. The researchers hypothesize that “it possible that the therapists’ restricted awareness of their countertransference contributed to difficulties in taking a ‘third position’ together with the patient and to challenge the patient’s pseudo-mentalization.”

There are several implications of this research. Two notable highlights by Werbart and colleagues center around the prevention of suboptimal therapy outcomes. First, they assert that therapists must be observant of contradictions and incompatibilities in their early assessment of patients, the therapeutic relationship, and the therapy process.

Specifically, when therapists experience positive and stimulating collaboration in conjunction with feeling a distance from the patient, this may be an indication that the therapist is not entirely in touch with the patient’s functioning and experiences.

“If the therapist one-sidedly focuses on the more well-functioning parts, there is a risk of no therapeutic change. This kind of incompatibilities and split tendencies in the therapist’s experiences may be difficult to recognize by novice therapists and experienced therapists alike, and has to be addressed in psychotherapy training and supervision,” Werbart and researchers write.

Finally, they encourage continuous assessment of patient functioning throughout the therapy process to inform and guide therapists’ approaches and adaptations of interventions. The therapist must also be willing to reconsider their initial assessment.

****

Werbart, A., von Below, C., Engqvist, K., & Lind, S. (2018). “It was like having half of the patient in therapy”: Therapists of nonimproved patients looking back on their work. Psychotherapy Research, 1-14. (Link)

I have a hard time getting past the small sample size of both therapists and clients. Not sure if this research does much to further our understanding of these problems.

Report comment

I had a psychologist who believed in the DSM, and found having a therapist who was only interested in defaming me with a DSM disorder, while gas lighting me, trying to convince me my real life concerns were unreal (I was trying to mentally come to grips with the fact my child had been sexually assaulted at the age of 3 by a board member of my child’s school, and perhaps also by a pastor), to be the opposite of helpful. Perhaps, if the psychologists and therapists stopped caring more about getting a “right diagnosis,” which is a DSM billable but scientifically “invalid” medical condition, and actually tried to help their clients with their clients’ real life concerns instead, the therapists would be more successful?

And given the reality that the primary problem, that the majority of those who are in the “mental health system” have, relates to adverse childhood experiences or child abuse. Today, over 80% of those labeled as “depressed,” “anxious,” “bipolar,” or “schizophrenic” are actually child abuse victims. Over 90% of those labeled as “borderline” are child abuse victims.

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

But today’s “mental health professionals” can NOT bill ANY insurance company for helping ANY child abuse victim EVER, because the DSM classifies child abuse as a “V Code” and the “V Codes” are NOT insurance billable disorders.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-child-does-not-have-bipolar-disorder/201402/dsm-5-and-child-neglect-and-abuse-1

Which is likely the reason why there are such huge percentages of child abuse victims mislabeled with the other billable DSM disorders. This is medical evidence today’s “mental health industry” is one gigantic child abuse covering up industry, which is illegal, since all those so called “mental health professionals” are mandatory reporters.

Perhaps it’s time to put an end to “the dirty little secret of the two original educated professions”? And the psychological and psychiatric industries should get out of the business of profiteering off of covering up rape of children en mass? Especially since silencing child abuse victims does also function to aid, abet, and empower the child molesters.

And rumor on the internet is the child abuse covering up psychologists’ and psychiatrists’ intended or unintended (due to a lack of foresight) goal of having pedophiles and child traffickers rule our world, has seemed to come to fruition, which disgusts most decent people. I guess the “mental health professionals” hate Trump and Putin so much because they’re against these horrific practices?

https://thegoldwater.com/news/5068-President-Trump-Signs-3-HISTORIC-Human-Trafficking-Bills

http://anonymous-news.com/putin-west-controlled-satanic-pedophiles/

Nonetheless, I believe all the “mental health professionals” would be much more effective therapists, if they got out of the illegal business of covering up child abuse, and actually addressed our society’s real problems instead.

The good news is I was able to scare my child’s preschool into closing it’s doors forever, after the medical evidence of the abuse of my child was handed over, they chose to close on of all days 6.6.06. Not the behavior of an innocent school, but I have no idea how many children were raped or worse at that school. And the other good news is when a mother gets her child away from the child rapists quickly, and actively works to keep her child away from all the invasive “mental health professionals” who wanted to get their grubby little hands on her precious, healing child. That child can heal and go from remedial reading in first grade, to graduating from university Phi Beta Kappa (with highest honors), plus he won a psychology department award. So those “mental health professionals,” who are now claiming child abuse causes the invalid DSM disorders, are likely incorrect.

There are huge percentages of child abuse victims in the “mental health system,” because today’s “mental health system” was intentionally designed as a gigantic child abuse covering up system. The system needs to be changed. Maybe the “mental health professionals” should at least make helping child abuse victims an insurance billable “disorder,” so you can stop misdiagnosing so many child abuse victims with the “invalid” DSM disorders?

Report comment

I agree with most of your criticisms of the system. We should not have to diagnose sufferers of trauma in order to provide treatment. Trauma survivors are given any number of DSM diagnoses, and these diagnoses also change over time because diagnosing is so subjective. Most of my clients have experienced multiple traumas in their lifetimes, and I know for myself I see this as the root of most, if not all, of my client’s “symptoms.” We do document specific traumas and, when appropriate, do report child abuse to the authorities based on what the law demands. I do not believe that “today’s “mental health system” was intentionally designed as a gigantic child abuse covering up system” as you say, but I agree that it needs seriously reformed. If we actually covered up abuse, we are liable to lose our licenses and face criminal charges. Anyone who is a mandated reporter has a duty to report suspicions of ongoing abuse or if an abuser is in a place of authority, such as a teacher or pastor. In many cases by the time I see a child abuse survivor the perpetrator has already been through the courts or the survivor does not want to pursue making a report to authorities.

Regarding Trump he has no standing when it comes to treating people with respect. He happily told a reporter that he sexually assaults women because he’s rich. Trump isn’t someone who cares about respecting other people as evidenced by his outlandish behaviors and commentary on women, minorities, immigrants, Muslims, and so forth.

Report comment

Shaun,

“Anyone who is a mandated reporter has a duty to report suspicions of ongoing abuse or if an abuser is in a place of authority, such as a teacher or pastor.”

I know that is the law, but your profession does not report child abuse. Especially when religious authorities are involved. The bishops of my former religion are also a bunch of child abuse cover uppers, as documented in this book, written by a justifiably appalled ELCA insider. I’d be one of the many “widows” mentioned in the Preface of this book.

https://books.google.com/books/about/Jesus_and_the_Culture_Wars.html?id=xI01AlxH1uAC

And I do have medical proof in medical records that my psychiatrist was terrified when I told him that the medical evidence of the abuse of my child had been handed over. He’d been massively poisoning me based upon lies from the pedophiles, I eventually learned from reading all my medical records. His first suggestion was to send my child (who was already largely healed, since the abuse had occurred four years prior) to a child psychiatrist. I said no.

His next attempt to cover up the child abuse was to try to convince my husband that I needed to be put back on antipsychotics, which I already knew made me “psychotic.” I eventually learned from my medical research, I was made “psychotic” due to anticholinergic toxidrome poisoning. We had to walk away from that criminal psychiatrist at that point, his name is Dr. Robert Kohn of McHenry, IL.

My pedophile covering up psychologist’s name was Dr. Barbara Grace of Barrington, IL. It was lies from her pastor, and his delusions of grandeur filled, Bohemian Grove attending, pedophile, possible cocaine dealer, at least according to a source, best friends, that resulted in the “mental health professionals'” initial misdiagnosis of me, according to medical records.

Here’s a book that pedo wrote which is evidence of his “delusions of grandeur.” I wasn’t aware of the fact the pedos were infiltrating school boards, so they had easy access to children, two decades ago. Nor did I know our society had a pedophile run amok problem then.

http://www.blurb.com/b/2934828-mag-men

All these people, as well as my life, were all declared to a be part of a “credible fictional story” by the lunatic Kohn. Of course I had to walk away then, what kind of sick moron has delusions of grandeur a person’s going to believe their entire life is fictional? Do you believe “fictional” people can write books and blog? I don’t.

Although, due to a drug withdrawal induced sleep walking and talking issue, once ever in my life, I was also subjected to the “snowing” and attempted “unneeded tracheotomy” for profit crimes of this now FBI convicted, ELCA hospital at that time, pedophile and malpractice covering up criminal doctor.

https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndil/pr/oak-brook-doctor-convicted-kickback-scheme-sacred-heart-hospital

It’s staggering the lengths today’s medical community will go to profiteer, as much as possible, off of covering up medical evidence of the abuse of one’s child for the religions. The “snowing” psychiatrist, a Dr. Humaira Saiyed, who was partners in crime with Kuchipudi, may even still be illegally listing me as her “out patient.” I don’t know, but I do know she was illegally doing that for years, according to health insurance companies. She even had me medically unnecessarily shipped a long distance to her in the middle of the night a second time. That time she couldn’t convince the other doctors to defame me with anything more than “adjustment disorder.”

And the police in Illinois have not been arresting or even looking into child abuse cases for decades. As a matter of fact, one police officer I spoke with actually told me I should discuss the abuse of my child with a psychiatrist, rather than the police. I told him arresting the child molesters was the job of the police, not the psychiatrists, he didn’t care.

And an ethical pastor did confess to me that “the dirty little secret of the two original educated professions” was that the “mental health professionals” have been covering up the “zipper troubles” of the religious leaders and their wealthy for decades, which is commensurate with your industry’s own medical literature. And I’ve learned the psychologists have been covering up “zipper troubles” since the days of Freud.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Freudian_Coverup

Illinois may be worse than most states, since we had the pedophile Dennis Hassett as our representative? But he was also everyone’s speaker of the house.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5a31o6AfjJw

The reality is the “mental health professionals” should NOT be covering up child abuse on a massive scale, but the truth is collectively you are, according to your own medical literature. And because your DSM is a joke, organized in a manner that insures mass misdiagnoses of child abuse victims.

I’m not interested in discussing Trump, but will suggest you turn off your TV, and do some research online. The internet is now filled with you tubers discussing our country’s and the world’s pedophile run amok problems, especially amongst our country’s and the world’s so called “elite.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZO3jtXv6jUg&t=304s

You know, the same “elite” that funded the miseducation of all our “mental health professionals” with the invalid DSM lies and the pharmaceutical industry’s fraud based research.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X6J_7PvWoMw

The “elite” who also give your industry the right to unjustly force neurotoxic drugs onto innocent people for whatever sick reason a doctor may choose, like the desire to profiteer off of covering up child abuse or malpractice. I do hope your industry changes, and gets out of the business of defaming, torturing, and murdering our society’s weakest members on a massive scale.

In part because “A nation’s greatness is measured by how it treats its weakest members.” I’m ashamed of my nation now, in part because it has a multibillion dollar, primarily child abuse cover upping, group of “mental health” industries. Although I’m against all the fiscally irresponsible, bailout needing, globalist banksters crimes and never ending wars as well.

I don’t want to “adjust” to our now completely corrupt society. I want a return to the rule of law, I want the never ending wars to end. I want a return of ethics to our monetary system, government, legal, judicial, and religious institutions.

Report comment

I do not consider the medical model of care “my industry.” I was trained to treat clients based on non-invasive treatments like EMDR, DBT, and CBT. LPC’s do not do drug-based therapy and never will. Social workers and therapists like myself prefer to help clients heal and increase their internal locus of control through natural means, such as psychotherapy. My co-workers and I would not cover up any child abuse. Keep in mind that our client interactions are confidential, and we cannot breach this privileged unless certain strict legal guidelines are met, such as suspicion of ongoing abuse. I do agree with you that a nation’s greatness is measured by how it treats it’s most vulnerable members, which is why I’ve spent the last 15 years of my life working with individuals who are homeless, low income, and trauma survivors, because I believe they deserve care and love to help them heal and move forward in life.

Report comment

Shaun,

“I do not consider the medical model of care ‘my industry.'” That’s great, but have the US social workers and therapists, as collaborating DSM compliant industries, spoken out against the past few decades of mass murder by the US psychiatric industry yet?

https://www.naturalnews.com/049860_psych_drugs_medical_holocaust_Big_Pharma.html

I know the UK psychologists have, but I’m not aware of any US “professional” DSM based organization speaking out against the psychiatrists’ iatrogenic illness creation, DSM classification system yet.

I personally would actually like to help child abuse victims, and know with 100% certainty that they can be helped with empathy, respect, confidence building, love, and caring. But when I look into counseling programs in universities, they’re all still teaching the DSM, which was debunked in 2013, by the head of the National Institute of Mental Health.

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml

I hope you will consider getting a group of your coworkers to work to convince your professional organization to denounce the DSM, and refuse to use it as a billing system. Since the DSM is merely a classification system of the iatrogenic illnesses that can be created with the psychiatric drugs.

Kudos to you for spending “the last 15 years of [your] life working with individuals who are homeless, low income, and trauma survivors, because [you] believe they deserve care and love to help them heal and move forward in life.” That is what our society needs, mutual respect, caring, and love of humanity based treatments. As opposed to only greed inspired treatments, which is what the DSM advocates.

And your industries need to work to make helping child abuse victims a billable service, which it is NOT in the current DSM billing system. And you should not need to defame people with “invalid” DSM disorders, in order to help them. So the universities need to stop teaching belief in the “invalid” DSM “mental health” billing system.

Please consider getting your co-workers to work to end their compliance with the fraud based psychiatric DSM billing system. We need American “mental health” professional organizations speaking out against the crimes of the American psychiatric industry, and their fraud based DSM billing code system.

Report comment

Someone else, thank you for your reply. Next month I do plan to present these topics to my coworkers. I do think we all in the system need to think critically about what we are doing and who we are doing it for. I for one know that a client of mine doesn’t need a diagnosis in order to get help, but that is how the system is set up. The premise is that the DSM is “the Bible” and thus is correct and accurate. There is also an assumption that prescribed pills are better than no pills, which I’m starting to realize is also false. Many clinicians say that the DSM helps give us a common language to understand the clusters of symptoms, but I think this is also unnecessary. We do need serious reform in mental health care.

Report comment

A common but misleading language that supports the power of those providing “treatment” over those who are its recipients without providing explanatory power of any significance.

.

Report comment

You may not consider the DSM as your model of care Shaun, but you speak out in favor of “treatments” that employ the bio-model.

Not quite the same of course. I guess that means you don’t prescribe the drugs yourself and maybe don’t offhandedly label all who walk through your doors.

Report comment

Rachel, EMDR, DBT, and CBT do not favor the bio-model. I would also add that vocational training and providing educational opportunities do not fit into the medical model.

Report comment

Steve, no doubt there is a power differential in mental health systems. Doctors are usually believed and sometimes coerce their “patients” to follow their recommendations. I don’t subscribe to this method of “helping”. I think all people should be fully informed of the risks and benefits of any treatment they partake in.

Report comment

“EMDR, DBT, and CBT do not favor the bio-model.”

I disagree. These are inextricably part of the diagnosis + treatment paradigm. Within those treatment frameworks is the belief that the patient (sometimes called a consumer or client) is injured and / or diseased in their brain (whether by genetic mutation or “environmental” cause).

I remember vividly sitting in a hospital outpatient treatment program that facilitated CBT and DBT. My urgent and dire crisis issues were not being dealt with (in favor of this pathological, medicalized, extremely awakening false “help” I was being subjected to). I walked out and never went back.

There is work to be done and until people recognize, understand and acknowledge the massive neglect that happens in the “help” industry it’s really just the blind leading the blind.

I have a “help wanted” sign in my window but I’m unable to secure the funding I need to hire and employ people to work for me. I need collaborators while I labor the construction of my Temple (mind) and Soul (my life and destiny). CBT and DBT have no place and serve no purpose in the material and substance I process and produce. I would have loved to have a chief of staff, and staff, to support the massive size of me (hint: do shrinks seek to minimize people, and shrink them, for a reason?), just like Michelle Obama had. She explicitly stated that the reason for her success was directly attributable to the support she had (take note: non-pathological support which means the support she had was not because she was “ill” or “disabled”) and she recommended that all women deserved the level of support like she had.

She could not function if she did not have all those extra arms and legs and hands and feet. If she had to do her work alone, she would break down and fall apart and struggle and suffer, and would lose herself, and would need “help”. if she’d be given help in the form of CBT and DBT she would probably lose her mind and go nuts at the massive distraction and derailment of those things, for knowing that what ailed her was mostly practical matters instead of disease.

Well, it’s all such an overly complicated thing.

Report comment

Heavenstobetsy,

I guess we can agree to disagree. DBT and CBT are used to treat any number of human suffering. I don’t think mindfulness, for example, requires a diagnosis to be helpful to someone. DBT encourages healthy self care (e.g, PLEASE skill), assertiveness to protect oneself from being used by others (DEARMAN), a deeper understanding of why our emotions exist and what use they are to us (emotion regulation), and working on learning to accept what we cannot change in life (radical acceptance). I don’t think these are abusive concepts; quite to the contrary, for those who wish to avoid pills and work on themselves, DBT and CBT are great alternatives, as they focus on individual autonomy and choice to change their lives through natural means.

Report comment

shaun,

I’m not sure why you failed to recognize and acknowledge the obvious: I’m talking about people of adversity (neglect, abuse, trauma, etc.) who are subsequently committed to diagnosis + treatment in the name of “help” when the “help” is not in the least addressing the practical matters in the fallout of life in adversity.

Can you understand the difference?

CBT & DBT were wholly and entirely irrelevant while going through such severe domestic violence that the threat of homicide hung in the air. That crucial time required a team of people paying attention to what was happening in the relationship, not wasting time handling a ball of playdough so I could later reflect upon what I felt while doing it (like as if I were incapable of feeling, and needed to learn how to feel).

Do you understand the point I just made? Does anybody? If so, please chime in.

No, I quite knew how to feel my feelings and articulate them; the problem was more practical and required a very different sort of “help”.

I ended up turning to prayer. That prayer changed my life in so many ways that psychiatry and the mental industry could not survive my *gnosis* of who they are and what they do. Years of laboring have produced SOME fruits, here and there, but there is still a long way to go.

You have a too idyllic image of psychiatry and the mental industry. It looks like devout worship. You’re glorifying, verily, while really not grasping what numerous people aim to teach you. But, as I said before, you are unable to identify with the monster. You probably very legitimately CANNOT see (blindedness).

Please don’t feel attacked. I’m currently speaking from a very neutral emotional and energetic place. There’s no active energy, feeling or emotion… I’m resting in peace discussing the facts.

Report comment

HeavensToBetsy,

You are right. You were not treated with dignity and respect, and it sure seems you weren’t listened to or given the help you felt was most appropriate for your situation. I would never suggest that CBT be the first treatment for a domestic violence survivor. That doesn’t make sense.

The general point I have been trying to make is that DBT and CBT can have benefit to individuals who are in the position and need for it. CBT for example has years of research to back up its use and has been shown to be quite effective at treating certain issues like anxiety and depression.

I am sorry to hear that you had such a poor experience with the system. I honestly feel we are doing better but nowhere near we need to be. The system does have problems and I hope one day it will get away from pathologizing all human suffering and instead meet the person where they are at without any threats, harm, or suffering being inflicted on the individual.

I have probably been influenced more by the medical model than I want to believe. I would like to think I don’t pathologize my clients, but the reality is that I’m forced to in order to admit any client into our outpatient programs. If they don’t meet any criteria under the DSM, I have to refer elsewhere. But if they have Medicaid, the chances of finding anyone that will take them without a diagnosis is slim. The system is also unjust because a rich person doesn’t need a diagnosis to receive treatment–they can just pay out of pocket. The rest of us must be labeled as “sick” in order to receive help. This is flawed on many levels. I am more concerned with what has happened to my clients than diagnosing them, but I’m forced between a rock and a hard place when it comes to providing treatment in America. HMOs and governments are a big part of the problem, too, because they push the agenda of diagnosis and pills.

I think that not enough of us who work in the field are questioning our role in keeping the status quo going. I do plan to talk more with my colleagues about my concerns, the same concerns that many MIA members articulate. Nobody should be harmed by the mental health system, but clearly this is happening all too often in one way or another.

Report comment

Thank you for your commitment to HONESTY and professional integrity, D.J. Jaffe!

Report comment

Someone Else,

Psychiatry and the mental industry malign people, particularly the ones who do not wear their Mental Health helmets well.

Some people DO wear their Mental Health helmets very well, which pleases NAMI and the APA.

Report comment

shaun,

“I do not believe that “today’s “mental health system” was intentionally designed as a gigantic child abuse covering up system” as you say, but I agree that it needs seriously reformed. If we actually covered up abuse, we are liable to lose our licenses and face criminal charges.”

The cover-up begins with the false, fabricated diagnostic labeling. Here is the way it works,

1. Sexual abuse is disclosed or reported. The victim enters the system through referrals or by order of a court.

2. Invasion begins. The victim is deceptively soothed and lulled into trusting, cooperating and opening up.

3. The victim is stripped down, psychologically, given tests and examinations (likely to occur in a hospital setting but may also take place clinically).

4. Formal diagnosis is made (this is a condemnation; it locks the victim into “the system”). Recommendations for “treatment” are made (and the “treatment” almost always includes a tranquilizer, aka “medication”).

5. By now the victim’s stress level is probably so severe that if they haven’t been hospitalized yet they soon will be.

6. Hospitalization process causes massive, irreparable damage. The BODY is stripped, one’s identity is stripped, one’s autonomy is stripped, one’s rights are stripped. It is at this time when the psychiatric head cage is permanently installed.

7. One learns the ropes: you are NOT to talk about your experiences (especially those of sexual abuse). You are to learn your illness. You are to learn your diagnosis. You are to learn your medications. You are to learn the system, and the way it works. You are to learn your patient rights. You are to learn mental health. All of this is the process of indoctrination and brainwash.

8. Upon discharge from brainwash school ( “hospital”) you waste away in outpatient counseling, therapy and group programs – all of which are the continuation and perpetuation of psychiatric concepts and diagnoses.

9. Polypharmacy has taken the victims so far from the starting point that some may never recover who they were before entering the house of darkness, psychiatry and the abominable mental industry.

shaun, do you recognize the cover-up that Someone Else labors ceaselessly to communicate to this massively huge (and deaf and blind) world?

Report comment

Heavenstobetsy, I do agree with some of what you say, here. I do think you describe an outlier example, but I could be wrong. Most of my clients are trauma survivors and haven’t experienced what you describe here. I will say that many trauma survivors are given drugs which do no good. I think proper treatments, like community support and EMDR are much preferable. My clients do talk to me about how they feel, and not surprisingly they get better over time because I think they are getting what they need–relationships with caring, safe individuals who validate their pain. Drugs will never remove someone’s trauma from their experience.

Report comment

shaun,

I have 28 years of experience with psychiatry and the mental industry. We’re looking at two contradictory products psychiatry and the mental industry produce; both are very real and true. Your angle on the matter is the reason why psychiatry and the mental industry continue to prevail.

Your angle on the matter involves a perpetual inability of the industry to be accountable for the prolific – not outlier – scenario I presented. The inability comes from a foundation of legality and criminality; there are no established and applied laws to inform psychiatry and the mental industry on HOW to be accountable for the harm, damage and devastation caused.

It’s the perpetual glorification of psychiatry and the mental industry that persist in effectively shunning, denying and preventing the truth from prevailing.

Of the contradictory outcomes of psychiatry and the mental industry: one side does not negate the other. Tragically, the side that claims benefit continues to obstruct the side that cries foul.

Report comment

Heavenstobesty,

There is a process for clients to grieve their mental health providers in my state. If someone thinks they’ve been harmed by their doctor, therapist, or social worker, they have the right and the ability to make a formal complaint with the licensing agency/board. An investigation takes place and people are often held accountable. Many clinicians get in trouble, for instance, because they have sexual relations with their clients. Anyone providing MH treatment ought to be held to a very high standard. If that isn’t happening, that is a failure of many systems which are supposed to be in existence to promote public safety.

One reality that I’ve come to believe in is that the world is unjust because monied interests are usually corrupt on some level. Money buys influence which buys laws that are favorable to powerful interests. I do believe that big pharma is corrupt, and any entity which has too much power is dangerous. Pharmaceuticals are the most profitable business in the world, and certainly big pharma is spending billions in advertising and influencing prescribing practices in order to keep the status quo going. I do believe, however, based on my own interactions with clients, is that some folks see immense value in having these pills as a treatment option. They report fewer nightmares, better sleep, improved moods, decreased voices, etc., and I cannot discount their stories simply because I think pharmaceuticals are too often problematic. That would also be short-sighted and arrogant on my part to tell them that their experience is inaccurate.

Report comment

shaun,

Once again, I am seeing from you a glorified, idyllic, problem-free wonderful picture in your first paragraph. The reality is quite different from what you profess.

Case in point: ask Paula Caplan how filing complaints worked out for her.

That’s just one of countless examples of how people do everything right and take all the required steps but their complaints go into the wasteland of ruins, one way or another.

Report comment

Heavens,

Well I can say that many people who are grieved in my state are held accountable, such as losing licensure and even being arrested. I know this system is flawed, but people do have a voice. At the end of the day the system (e.g., government) gets to determine the outcome, but all of us should do our best to hold people accountable.

I assume you are referencing Paula Caplan’s complaint to the APA around diagnosing/DSM? This complaint is different than what I’m referencing. State boards have nothing to do with the APA. They follow their own standards of care, such as that a clinician cannot sleep with their client or have a dual relationship. The APA clearly has a monetary interest in keeping the status quo, so of course they’d dismiss Caplan because then it would require them to admit the significance flaws of their DSM.

I do like Caplan’s quote: “The ultimate aim is to get professionals and the public to stop assuming that what’s most needed is to know what the person’s diagnosis is. What’s most needed is to listen to what happened to the person and to find ways that help.” Amen to this.

Report comment

The power balance is so skewed that most clients are afraid to use any “grievance process” for fear of being further abused. This is especially true for anyone diagnosed with any kind of “psychotic disorder.” It is very easy for those in power to dismiss any complaints as “symptoms of their disorder.” I am aware of a situation where multiple sexual abuse complaints against the same person in a MH facility were dismissed out of hand because the clients “were not reliable witnesses.”

This is what I mean by disrespecting the voices of those who have been there. It’s easy for you to say, “Use the grievance system.” You are a person in power. It’s very different to ask clients who are IN your power to do this. There ARE people in the MH system who abuse their power, and they are NOT rare. Consider the implications of filing a complaint for someone who has been forcibly hospitalized and “treated” against their will on multiple occasions. Don’t you think the impact of the huge power differential and potential costs of complaining would weigh heavily against trusting “the system” to do the right thing?

Your ability to believe the best of your colleagues is remarkable, but not supported by the reports of those using the system.

Report comment

Like I said, Steve, there are consequences for some clinicians who break the law. You are right that people are too often dismissed when they have a diagnosis, but this isn’t always the case. People in power always have an advantage in any system and any society. I never said it is fair or always just. But people do get grieved and there are serious consequences for some. That is all I’m saying.

May I ask, what other options do people who are served in the system have other than to use the grievance system? I am seriously asking. If they feel wronged by their “helpers”, what other reasonable measures would you suggest? They frankly don’t have many other options, other than to sue for civil damages. And how many folks can afford an attorney?

Report comment

You got the quote wrong. Trump bragged–quite tastelessly–that many women came onto him because he was rich and famous. That is pretty disgusting though.

I’m sure you approve of Trump’s new mental health czar though. Right D.J.? Lol.

Report comment

Due to their alliance with psychiatry even well meaning psychotherapists who care about people are unable to do much. For one thing they encourage mindless, unquestioning “meds compliance” regardless of obvious deterioration since starting the drug. For another they are pessimistic and cynical. Understandable since the bio bio bio model makes true recovery impossible. Life long labels are also to blame.

The only way to get better? Run far away!

That’s my recovery story.

Report comment

I’ve had a gang of serpents and demons perform psycho-something (not sure I’d call it psychotherapy) on me in the Temple. They did a bad job! I now have such great knowledge of evil that I have to wear sunglasses at night.

The Lord saves! God told me (via scripture) that perfect Love can do away with knowledge. When I learned this truth a seed of Love was placed in my heart (the heart is the brain of the soul). How I long for my Temple (that’s the religious, biblical, holy word for mind) to be cleansed of perverse and scarred knowledge! How I long for the light of Love to fill me and do away with all this darkness!

I need an exorcism. These demons are too much. I have just enough hope and faith that maybe some day I can be LOVED, liberated, delivered from evil, cleansed, saved, healed and restored.

Psychiatry and the mental industry are the house of darkness. Jesus is the light of the world.

Go to the light. Seek the light.

Report comment

My psych drugs opened my soul to demons. Mind altering drugs have been used throughout history to invoke the spirit world. So it makes sense. Deliverance helped me even before I went off my drugs.

If you want, I can direct you to a friend of mine who runs a ministry. We dated for a while.

My email is r dot nichols 42 at yahoo dot com.

Report comment

Hi Rachel, thanks for the reply. I admire your commentary! We must be kindred spirits 🙂

I’ll add your email to my address book. Thanks 🙂

Report comment

I think questioning the opening statement ‘There is extensive evidence suggesting psychotherapy is effective for a wide-range of mental health concerns’ would demonstrate that this is not true – there are many critics of the poorly controlled, unreproducible, rubbish research out there here are a couple

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cu5CxJnZqGs&t=1s

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Therapy-Industry-Irresistible-Talking-Doesnt/dp/0745329861/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1530025757&sr=8-1&keywords=the+therapy+industry

https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/1627345280/?coliid=I250WNQ6HG0T1H&colid=2ISQ48VSYRFBD&psc=0&ref_=lv_ov_lig_dp_it

there are many others – how can any therapy really help beyond what David Smail suggested of comfort, clarification and encouragement – mental health problems are not personal issues but meaningful results of a disordered culture/experiences

Report comment

Chris,

Thank you for sharing these resources. I will take a look.

I do think therapy can help in innumerable ways, such as identifying possible changes in areas of their lives which we control. Ultimately, therapy is a powerful tool if focused productively and thoughtfully. I try to stick to Carl Rogers’ core tenants of therapy and throw in a few other ideas along the way. I fully believe it is the safe relationship in therapy that really matters, not what techniques are used. I don’t see CBT being harmful if done in a thoughtful manner, because it points out the connection between thoughts, feelings, and behavior. If our thoughts are distorted/exaggerated (they don’t fit the facts of the situation), such as when I say “He’s an idiot for cutting me off in traffic”, it may lead me to feel stronger negative emotions such as rage which for many can lead to unhelpful behaviors, like pulling out a gun and shooting someone (recently in my community and guy shot and killed multiple people after such an incident). Thinking errors are something we all struggle with, such as “I’m a loser” or “Things never work out for me.” These types of thoughts don’t usually fit the facts, but we believe them anyway. No doubt the environment impacts all of us, and if we live in a toxic world, we will feel badly at times. But the truth is we cannot fix these social problems in the therapy setting; we can only work on the piece in our lives that we have any control over. This is the point of any good therapy to help us see our contribution to our own suffering and to also get validation of our pain and struggles in a safe environment.

Report comment

There’s also the issue of HONESTY. Being true about who we are. And not lying to others. 😀

Report comment

Hi Shaun F, I wonder, perhaps longer term therapy might be helpful for some people some of the time especially where a trusting relationship has been developed but short term therapy seems to have been completely oversold in the culture. Having said that if we lived in healthy cultures with healthy relationships etc I am sure therapy would seem ridiculous.

We just need to consider the evidence -we’ve had around 100 years of clinical psychology and the hundreds of ‘talk therapies’ it has spawned – we’ve had much longer with psychiatry and we’ve also got dozens prescribed drugs – after all this ‘evidenced based’ practice have we better wellbeing? improving wellbeing? less suffering?

clearly not year in year out suffering increases – we now live in cultures where the largely culturally induced issue of depression is now our common cold and this is just accepted like its to be expected.

Most therapy offers people a place where after say 6- 25 x 50 minute sessions with a therapist you are expected to become good self monitoring robot able to sift through the vast complexity of influences and powers that constantly surround us in order to choose the correct thought for the correct emotion and behavior – in fact we’re not expected to sift through the vast complexity but to somehow just pretend it doesn’t exist and just come back to reducing the irreducible your ‘thinking errors’ these might seem like errors but are they really?

if we add in the complexity that therapy ignores, obfuscates or plays lip service to then surely they are reflections of our disordered world and unless and until we foster not insight but outsight we shall all remain vulnerable to more suffering than is needed.

Report comment

Hi Chris,

I think you make some important points here. Our world is very complex, and in toxic environments we can’t expect people to feel safe and healthy. Also, you are right that therapy has not drastically improved overall happiness or well being in this world. Therapy does not prevent social problems like poverty, discrimination, wealthy inequality, war, and government corruption.

Short-term therapy is basically what HMOs love. They want to be able to pay as little as possible for treatment, which is why long-term therapy isn’t favored in many places. Very few clients I’ve ever met who want therapy prefer the 8-12 week model, but there are some who do, who want “tools” to work on very specific goals.

And to be clear most evidenced-based therapy today hasn’t been around for 100 years. Only psychoanalytic has been around that long, and hardly anyone uses this modality anymore. Most of us who practice are eclectic–so we use a combination of person centered, CBT, DBT, EMDR, MI, existential, reality, trauma-informed, and so on, based on the individual who presents to us and what their goals are.

Ultimately, therapy isn’t a panacea for the world’s problems. My hope is that it can help people to reduce their suffering, increase their sense of autonomy and peace, increase their belief in themselves, and to help heal from traumas.

Finally, I will point out that therapy is utilized in countries which are more individualistic. Collectivist cultures support each other more and fewer people feel isolated. Whereas in the West, too many of us feel like we are a man on an island and have nobody to turn to. This to me is one of the big explanations for the despair people feel (and thus their symptoms of depression, anxiety, etc. are a manifestation of this experience); so many of my clients tell me that they have nobody but me who listens to them. This makes me understand why therapy is necessary in cultures like my own where people do not get enough support from their immediate community and neighbors. I know nobody on my block, for instance, except the people who live in my building. This is a a common problem in the US. And certain no drug is going to fix this sense of isolation and disconnection. I can see why suicide is common under such terrible circumstances. Most of us yearn to be understood and loved, and if we don’t have meaningful social connections, this is impossible.

Report comment

Hi Shaun – thank you for your thoughts.

When you said ‘Therapy does not prevent social problems like poverty, discrimination, wealthy inequality, war, and government corruption’ I found myself in full agreement and then found myself wondering how individualistic therapy located in cultures biased towards extroversion, soaked in images of the hero and personal responsibility actually serves power to maintain the toxic status quo?

Take CBT as an example with its declaration that it is based more in the here and now and basically claims the world is okay but your thinking, attitudes and beliefs are the issue.

The models are all reliant on the language of psychiatry GAD, PSTD, Depression, OCD etc and also, like biological psychiatry reduces the world and its systemic causes of harm to mere triggers for some hypothesized personal pathology – then after reducing the irreducible and therefore hiding the real causes of suffering it converts it into a mission of personal responsibility to do your homework, self monitor and simply select the correct thoughts and emotions from a sort of illusion of rationality.

EMDR is just another form of exposure therapy that is often hard for people to do and I also think the idea that we can just ‘tap in resources’ like a ‘safe place’ or ‘wise benefactor’ etc is ludicrous – what we get is usually clients people pleasing – i’ve asked plenty of people about the processing aspect of EMDR and from the outside in, it would have looked like a textbook success reduced affect, lowering SUDS etc but most tell me it did nothing = what they do value and find useful is sharing their story with someone compassionately interested in it, something any of us could do for each other if we had cultures that helped rather than hindered human connection.

on the point of connections you might enjoy this book

Lost Connections: Uncovering the Real Causes of Depression – and the Unexpected Solutions

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Lost-Connections-Uncovering-Depression-Unexpected/dp/1408878682/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1530180332&sr=1-1&keywords=johan+hari+lost+connections

and on the subject of power you might enjoy these

Power, Interest and Psychology: Elements of a Social Materialist Understanding of Distress

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Power-Interest-Psychology-Materialist-Understanding/dp/1898059713/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1530179439&sr=8-1&keywords=david+smail+power+interest

Psychology and Capitalism: The Manipulation of Mind

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Psychology-Capitalism-Manipulation-Ron-Roberts/dp/1782796541/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1530179501&sr=1-1&keywords=ron+roberts

be well

Report comment

Hi Chris,

Thank you for the thoughtful dialogue and sharing of resources. Humans living in a toxic world will be impacted by the environment, and I see my role as a listener, validater, and to help them identify how to cope with what they cannot change. The truth is that virtually everything happening around the world is out of our hands, and this is where concepts such as radical acceptance are useful (and very difficult!) to practice. Ideally therapy helps to reduce suffering and increase a sense of autonomy and empowerment. Most of my clients have a low internal locus of control due to their traumatized childhoods and adulthoods, and I do think therapy can help to work to increase that sense of internal control. Regardless of how toxic our world is, we do all still have personality responsibility to ourselves and those around us. If we don’t take responsibility for ourselves, who else is going to do this? Who is going to shower, feed, and clothe me but myself? We all learn ways of coping, and some ways are more destructive than others. Using substances to numb out, for instance, is an example of this. No doubt we engage in addictive behaviors in individualistic countries because we are trying to soothe our pain of isolation.

I do worry that with many of my interventions people are telling me what they think I want to hear. I try to tell them that I don’t care what the truth is, but that I prefer the truth. There will always be a power differential in the therapy setting, and I try to do my best to lessen this, but it will always be lurking no matter how I try to diffuse the situation.

Regarding your CBT critique, I think CBT basically posits about the outside world that you cannot control it. CBT is about our own interpretations and reactions to events. I think we all engage in cognitive distortions to one degree or another, AND some people engage in them to such an extent that it creates roadblocks for them. Road rage is a common example I use. If we get angry every time we are driving, it isn’t the fault of all the other drivers that this is happening. Something is going on within me which is causing the additional suffering. I think we can say that our own reactions, just the like world around us, can be toxic.

If we all can learn to be most effective at taking care of ourselves, we have a better chance of changing the world. My hope is that therapy can assist traumatized individuals in tapping into their own strengths, power, gifts, and internal resources so they can go out into the world and make it a better place.

At the end of the day human connection is key. Human connection is why MIA exists. People sharing their stories, supporting each other, connecting to each others’ pain.

I think therapy will always be necessary in the world we live in for all these reasons, and certainly EBP’s aren’t necessary in the work we do. I generally try to be like Carl Rogers if possible, showing my clients authenticity, unconditional personal regarding, and empathy. They at least deserve that.

Take care and be well. Thanks for the dialogue.

Report comment

I forgot to mention the idea of universal basic income and housing. If every man, woman, and child was guaranteed these resources, I am certain many people would not be seeking out a diagnosis. In order to receive many of these services in my area, one has to have a “disability”. We sign off on government documentation for housing, income, transportation, loan forgiveness, food stamps, and so forth, per our client’s request. All of these documents more or less have to state that the applicant has a diagnosis that prevents them from being employed or something similar. Many of our clients come to our center because they know we can help them in these areas. I understand why the system is set up this way, as the government does not want to provide basic, affordable services to people who can legitimately work. But it then does create a certain dependency on the system for those who think they cannot work because they’ve been told by doctors that they have various mental health disabilities. Because all humans have needs, we seek out whatever resources are at our disposal in order to meet these basic needs of survival. The net outcome of this flawed system is that people receive treatment they don’t want, need, or that makes them feel worse, get diagnoses that don’t help them, get stuck in a system they cannot get out of, and further a sense of helplessness. There are clients who get out of the system, but if I’m really honest with myself, they are in the minority and usually have other safety nets to utilize, like family support. I do believe community mental health does good things, and we are also a part of the problem.

Report comment

Young adult is almost an oxymoron. Adult child is an oxymoron. Give them time, and they might amount to something yet.

My view….It’s not a good idea to give psychiatric labels to young and impressionable people. Once they grow old and set in their ways, that’s a different matter altogether. Labeled youths tend to grow into labeled adults. Refrain from labeling them, and who knows how many people you might have just saved from a life in the “mental health” system. Of course, non-treatment doesn’t pay the bills, but you will get over it.

Report comment

There are honest ways to pay the bills, Frank.

Sad how everyone wants money for being kind now. You shouldn’t nave to pay someone to listen to your pain.

Stay away from shrinks with their labels and drugs. Then you can make real friends and may not need a therapist.

Report comment

Hi Shaun F – thank you too for your thoughts, ideas and respectful communication.

I must say I find the idea of radical acceptance quite frightening as I do industrial systems of therapy like IAPT in the UK.

I find myself pondering the thought, if we had these ideas/systems so firmly embedded in the culture and largely aimed at the working classes earlier in our history would we have what we have today?

namely:

A history of working class struggle where ordinary people stood up against the government and their class position and made demands to absolutely NOT accept the rubbish conditions and servitude they and their children suffered in – these brave, courageous people did not just ‘get on with it’ but fought and died in the streets so we might have such things as an 8 hour work day, time for recreation and rest, and so our children would not be stuffed up chimneys and thrust down mines – so we might have some basic benefits like holiday pay and sick pay, the right to vote etc.

no these people did not have what I can only think of as a major play into the hands of power ‘radical acceptance’ or considering themselves to be disordered and in need of therapy –

NO these people knew that in order to change things for the better they must change the world and this can only be done in radical solidarity with others not some futile attempt to simply change yourself to just ‘get on with it’

This is a sickness at the heart of our culture and looked at from this angle individual therapy is certainly holding us back. as are the labels and the drugs – we’ve now reached the stage where we are begging to be labeled, drugged and therapised in order to delude ourselves into some personal/individual gain in the form of perverse incentives or scraps from the table in the form of benefits or just to be left alone.

Why aren’t we as therapists helping people to see and connect with the structural abuse and the gross limitations of changing our individual selves and offering people encouragement and support to get together to change the world? David Smail might argue because of self interest.

maybe this could be a place to start https://b.3cdn.net/nefoundation/f49406d81b9ed9c977_p1m6ibgje.pdf

Report comment

Hi Chris,

Good points. Regarding radical acceptance, I think people have misconceptions of what it does and doesn’t ask us to do. I like Marsha Linnehan’s description and definitions; she says that what has to be accepted is reality as it is (the facts of the past, like my father’s alcoholism or that 9/11 happened), accept that we all have realistic limitations (there are things I cannot do), that everything has a cause (e.g., my grandparents (who had their own trauma) abused my parents which caused them to feel low-self esteem), and that life can still be worth living despite painful events. She also goes on to point out that rejecting reality doesn’t change it, and that acceptance and change go hand-in-hand, whereas rejecting reality doesn’t change it. Refusing to accept things as they are keeps us stuck in unhappiness, bitterness, anger, sadness, etc. She also says the path through hell is misery, and that by refusing to accept the misery that is part of climbing out of hell, we fall back in.

Regarding your example of socio-economic injustice, the working class people accepted reality that they were being abused and they stood up for themselves. There are many famous cases of this in history, such as MLK Jr. for civil rights. If these people did not racially accept there is something seriously wrong in the world, they wouldn’t have acted. The interesting part of acceptance is that it frees us to act. Without acceptance, we reject reality and suffer more as a result. The truth does set us free, even if we don’t like what the truth is.

The serenity prayer also comes to mind. I find that when humans focus on what we cannot change in life, and say how horrible it is, we get stuck and suffer. When we put our energies into what is possible, we feel empowered and uplifted. Therapy can be used to help the the individual and society. If the individual is suffering less and enjoying life more, they do impact those around them. Of course therapy is usually a slow process, and we don’t exactly know what will change in that system they are in. I can say that some of my long-term clients take a while to make important changes, like leaving toxic relationships (because of childhood trauma). This is still a worthwhile process to help someone to come to terms with their reality and to help them see the power they actually do have to make profound changes for their well being. I don’t see therapy helping to create world peace, for example, unless every man, woman, and child was provided this resource. And not only that, but that everyone’s basic needs were met. I doubt we’d have war if everyone was clothed, fed, treated with respect, housed, provided necessary medical care, and so forth. But we live in a world which is full of trauma, chaos (e.g., Syria), and poverty, because wealthy, corrupt interests rule the world. We have to keep fighting, and I think therapy is a tool to help empower individuals to improve their lives, families, and communities.

I could certainly talk a lot about how I think capitalism is also apart of the larger problem, since so many people are unhappy be a slave to their employers. Most people in America need two incomes to pay their bills, and this puts immense stress on the family unit. Also, because employment is so closely tied with identity in America, people feel lower self-esteem when they are unemployed, underemployed, or “disabled.” Most of my clients want to work, but they also want meaningful jobs. We exploit people in capitalism just like we exploit resources. We use them until they no longer provide utility, then we discard them. Reminds me of how we treat the elderly. Toxic systems will never make humans feel healthy, even those in power, because deep down they are anxious about how long it will all last for them to benefit.

Thanks for the thoughtful dialogue. Have a good weekend.

Report comment

Thank you Shaun- I wonder who decides when someone is ‘Refusing to accept things as they are’ and surely being ‘stuck in unhappiness, bitterness, anger, sadness’ is absolutely necessary because those powerful emotions are also channel for change through direct action.

Sadly many people experience legitimate but often misdirected anger and are not helped to understand the broader rational for their anger but are most often directed towards something like an ‘anger management course’ or a ‘low self esteem course’ or some individual therapy where they can learn to ‘manage’ themselves and simply get on with it – my main point of concern is that the mental health system we have appears to be fundamentally obfuscating and colluding with cultural/systemic disorder and power abuses and is also defusing possible collective actions to bring change to the system not each person’s own supposed gains. Sadly this anger is being cynically used by the ruling class to further hide the gaze from themselves and misdirect the anger by scapegoating other groups of ordinary people so we fight with each other – it seems divide and conquer is in full swing

Report comment

Chris,

Ideally the individual decides what needs to be accepted. I think of situations where my clients are on probation and choose not to follow the requirements, like take random UAs, because they disagree with the system. They refuse to accept the reality of the situation, and then they face the consequences of being sent to jail or having probation extended. They may suffer more because they do not comply with the law. They don’t have to agree with the reality, and I would say accepting the situation as it is rather than as they think it SHOULD be goes a long way in being more effective to get the desired outcome (e.g., off paper).

I agree with you that the broader society/systems scapegoats individuals, which is why you see these anger management, et al. classes. It’s easy to blame the individual for their anger rather than look at what could be contributing to it (like disrespect from an institution).

Emotions give us useful information; however, they aren’t necessary rational, either. Rage, for example, quickly turns into danger for self and others. Rarely does a situation actually call for it. And love, for example, binds people together; however, if I love an abusive person, I often stay in a toxic relationship which hurts me.

No doubt there is collusion going on within these various systems. The DSM is a perfect example of this. The reach that the DSM has in society is astounding, but to whose benefit? I would it benefits big pharma, APA, and psychiatry.

Report comment

Chris,

Yesterday was a tragic example of when “refusing to accept reality” turns to violence. A gunman opened fire at a the Capital Gazette and killed five innocent people because he had a grudge against the paper for a story that was written about him years ago. Las Vegas is just one more tragic example of rage going awry, and 9/11, etc. We as individuals have a responsibility for our own acts, and we have responsibility to help each other. This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t fight against unjust systems, but if we don’t start with our own behaviors, I don’t see how any society can be stable. No matter how angry we are, we need to know that lashing out at innocents is never the answer. Just because my boss writes me up, it doesn’t mean I have the right to kick the dog or punch my wife. My boss and the system he could be working for could be complete shit, but then it’s up to me to do something about it, like get another job. We can blame systems for all the ills in the world, but what is that going to change? Which individuals are actually responsible? There are so many people involved for keeping toxic systems going (self-interest). Radical change at a global–even local–level is very difficult to attain and maintain. Getting any kind of consensus from a large group is near impossible, such as the case with global warming, abortion, gun control, education policies, and war. The last election in the US is a shining example of the culture wars, polar opposite positions, hate, and so forth.

Report comment

Hi Shaun – these are interesting aspects about us as human beings and our conduct that you bring up.

When I read your words and the language of ‘responsibility’ and ‘not accepting reality’ etc I am reminded of the age old and unresolved debate regarding free will. After listening to thousands of stories over the years and observing myself living alone for around a decade I often wonder about this.

When I consider the vast array of influences and powers shaping me and the world around me (most of which are out of my awareness) I am often left wondering just where does this ‘free will’ emerge from?

My conscious thoughts are utterly out of my control, my behaviors very often feel automatic as does my speech and even this conversation we are having. however it feels like I am driving this but is it more that I can observe, reflect and think about it all and while this seems to give me some element of control its mostly just happening to and through me – I don’t know?

When I look within there is no one place where ‘I’ exist but rather ‘i’ am a vastly complex collaboration of internal and external influences that somehow produces this unique human being.

I did not chose my family, the country I was born in, when, the political system, the class, the intelligence (or not!) that I am bundled with, the opportunity that comes (or doest) come my way, I could go on but you get the picture I am sure.

Luck seems to be a sort of magic we all dance with – BUT we live at least in the west in cultures infused with the image of the hero, the self starter, the, self self, self – the community the collective the collaborative is reduced – yet human beings have only managed to harness parts of the worlds potential by working together.

Consider our totality – we are a vast collaborative effort of trillions of cells – none of which ‘we’ can control or direct in any way and when they fail we fail.

now the system around us is open to change and the system as is affords certain groups an abundance of opportunity and freedom while crushing it for many- changing systems has to be a collaborative effort.

its not necessarily about blindly blaming the ‘system’ or getting angry at it but observing and discussing how the system and its powers operate and being honest about our individual attempts to change ourselves rather than identify and seek to change in collaboration with others the system.

It seems we are like a beautiful flower grown in the conditions for life and thriving then planted out in the dark on rubbish soil and when we whither, suffer and diminish, we try and talk to the flower and pour artificial feed in the form of therapy and its ‘tools’ onto it. perhaps this gives the flower a temporary but ultimately futile perk. suffering is massively increasing year in year out, suicide up, human misery up – this must and has to change.

we need to work together to create the conditions for life to flourish we have all the possibility and tools we need but we have poverty of access hence the power of the system as it is to maintain divide and conquer

Report comment

Chris,

Well said. I don’t disagree with the philosophy of what you presented around free will. My main point is that we as individuals, despite everything you just said, still have a responsibility for our own behavior and how we treat others. If I continue to road rage, for instance, I need to ask myself why do I continue to act this way. If I want to buy a gun and shoot innocents, I need to ask why is this justifiable? We do need to acknowledge the system, and work to change it as well. And we as individuals can’t blame society for our own bad behaviors.

Report comment

Hi Shaun – I agree we must be able to ask questions of ourselves but changing ourselves significantly is another matter and requires access to resources and power.

I suspect if we were to really delve into the reasons for the examples you gave such as road rage or mass shootings we would see much more clearly that it is not individual malfunction, such as disordered thoughts or attitudes that somehow just need evaluating and correcting but would highlight instead a systems failure within the culture – we need to take an outside in approach and zoom out of our lives to help us see beyond the obvious and into the hidden – people are suffering in a multitude of ways sometimes obvious quite often not obvious but suffering in the form of many paper cut harms that accumulate over time and we often ignore, distract or dissociate from and therapy hides us from.

for me its not about blaming society but looking at how it shapes us all.