A new study, led by Matthew Pugh, acting outpatient lead clinical psychologist at the Vincent Square Eating Disorders Service in London, explores the association between an internal eating disorder ‘voice’ and childhood traumatic experiences. The results of the study, published in Child Abuse & Neglect, indicate that childhood emotional abuse is associated with the experience of an internal eating disorder voice and that dissociation mediates the relationship. Additionally, individuals may experience stronger negative thoughts and behaviors related to eating when the internal voice is experienced as benevolent.

“Overall, these findings add to the growing evidence that early adversity may be linked to the development of voice-related experiences across clinical populations,” the researchers write. “In addition, they lend support to the hypothesis that internal voices arise from detachment from internal events related to early trauma, which are experienced as alien due to dissociative processes.”

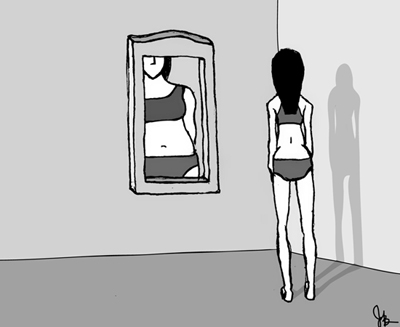

Editorial Illustration” (Flickr)

It is common for individuals with eating disorders to report an internal ‘voice,’ which the authors described in a previous article as “a second or third person commentary on actions and consequences relating to eating, weight, and shape.” Research suggests that 33% of individuals diagnosed with anorexia nervosa and up to 96% of individuals in mixed eating disorder samples experience an eating disorder voice (EDV).

Qualitative studies suggest that an EDV follows a typical progression of initially being a positive presence that aids in decision making, but becoming increasingly critical, leading an individual to feel trapped. Individuals may begin to resist or rebel against the voice and reclaim their autonomy. The authors connect EDV with the trauma-dissociation model of voice hearing, in which:

“Internal voices may represent decontextualized cognitive material arising from early traumatic events which intrude upon conscious awareness due to dissociative processes. In this way, internal voices can represent meaningful embodiments of traumatic events and early interpersonal-emotional conflicts.”

Research suggests a connection between disordered eating and childhood trauma, including sexual, physical, and especially emotional abuse. In the present study, the researchers sought to “establish whether cognitive and trauma-related models of voice hearing apply to experiences of EDV across ED [eating disorder] subtypes.”

The researchers conducted a cross-sectional study involving 85 participants who met criteria for an eating disorder (e.g., anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, other specified feeding and eating disorder, or binge-eating disorder). Ninety-two percent of participants were female and 74% were White. Participants completed self-report questionnaires on eating disorder symptoms, the power of EDV relative to the power of the self, beliefs about voices, dissociative experiences, childhood trauma, and voice frequency and distress.

Results suggest that greater levels of EDV power, benevolence, and omnipotence are associated with higher levels of disordered eating. A significant finding is that greater histories of childhood emotional abuse were associated with stronger EDVs, whereas histories of childhood sexual or physical abuse were not. Findings also indicate that dissociation is a partial mediator in (i.e., partially explains) the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and a more powerful EDV.

The present study is the first to establish a connection between childhood trauma, dissociation, and eating disorders. The researchers highlight that a more benevolent voice was paradoxically associated with more negative thoughts around eating. They speculate that many individuals engaging in disordered eating view their behaviors as positive, and therefore a benevolent voice is consistent with their perspective.

Based on their findings, the authors suggest that EDV be understood through a developmental, interpersonal framework. They make a number of recommendations for treatment. First, clinicians working with individuals describing an EDV should assess for childhood trauma, focusing specifically on childhood emotional abuse. Also, individuals diagnosed with eating disorders may benefit from dialogical approaches that work with their internal voice and family-focused interventions to address emotional abuse. Lastly, the authors suggest:

“Developing explanatory links between childhood adversity and the EDV may help contextualize voice-related experiences, support meaning-making, and bolster personal empowerment.”

****

Pugh, M., Waller, G., & Esposito, M. (2018). Childhood trauma, dissociation, and the internal eating disorder ‘voice’. Child Abuse & Neglect, 86, 197-205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.10.005 (Link)

As usual, the most important factor was left out. Were these individuals in treatment for their EDs? This is so important. I believe the ED voice is treatment-induced. I have seen the believe in the ED-Devil-like character induced in treatment, coerced into patients by therapy. This is caused by exposure to ED-specific therapy. Those who have not had this type of therapy do not have an ED voice and have never heard of such a thing. All you have to do, if you want to induce an ED voice, is to pester a patient, repeatedly, “What is ED saying?” Just ask that a bunch of times, obnoxiously, expecting a response. Ask like ED is a real person that has taken possession of the vulnerable, trapped patient. Now, the patient is more trapped. By the imaginary Devil ED. Very good job. You have succeeded! Now you have a guaranteed Revolving Door Syndrome.

Report comment

The “mental health professionals” do believe everything, from dreams to gut instincts to one’s own thinking to unknown voices in parking lots, is a “voice.” “Voice,” “voice,” “voice,” everything’s a “voice” to the crazy “mental health professionals.”

Report comment

They use Ed as a way to control patients. Those of us who have been in this sort of “care” see this technique used regularly on patients. If you question the rules, that is Ed speaking. If you ask to be released, that’s Ed speaking. If you dislike your therapist, that’s Ed again. If you ever dare speak of human rights, it’s surely Ed. They demand that you banish Ed from your head immediately by holding onto a frozen orange or they might hand you some pills or make you do very gentle yoga or color-by-number. Yes, it’s abuse, but as soon as you point that out they’ll let you know your eating disorder is surely to blame. Being human is a symptom, speaking out a disease, asking for fair, humane treatment is pathological. Your best bet is to vandalize the place, maybe write terrible swear word on the walls in permanent crayon. They’ll have to kick you out if you do that. Then you are free and you’ll get your rights back.

Report comment

Yes, the “mental health system” is all about abuse of power.

Report comment

Quite. I am unclear as to whether the researchers distinguished voice-hearing from negative self talk. I am encouraged that they are exploring trauma as a factor in eating disorders though.

Report comment

Sounds very weird. But this is the “mental health” system we’re talking about after all.

Is there a higher amount of therapist abuse involved with ED “treatment” Julie? You have had some really bad experiences.

Report comment

Yes Julie (sadly departed),

You describe it exactly, as it is.

[I had ‘something’ similar with a doctor some years ago when I made a realistic and legitimate complaint. The doctor recorded me in my notes following this verbal complaint as “..mildly agitated but with no sign of thought disorder…”, so I complained again expressing it in writing.

And that seemed to ‘work’….]

Report comment