At the end of my recent presentation about psychiatric drug withdrawal, a single comment was made aloud: “This is dangerous. Are we going back to Haldol?”

The person who asked this question was the chief of a psychiatric department, and I believe he was referring to one of the arguments in favor of drug withdrawal that I had made. There was, I had said, “not enough evidence to affirm that the new antipsychotics, the so-called atypical or second-generation antipsychotics, are more effective than the ‘classic’ or first-generation antipsychotics in alleviating psychotic experiences.”

At that moment, I am afraid that I did not dare, nor had the instinct, to ask what danger he was referring to. Danger to the patients if they were to be treated with classic drugs, denying them the advantages of the newer ones? Danger to our professional status should the standard prescribing practices of the last 20 years be questioned? Danger to the pharmaceutical industry if it turned out that the efficacy of current treatments was no better than the previous ones—even though they were much more expensive? Danger to society if the fabulous investment by developed countries in new antipsychotics for controlling symptoms were to prove inefficient, or even harmful to the population?

The Case for Withdrawal

I have been working as a psychiatrist for the last five years in Toro, Spain, a semi-rural community in the province of Zamora with a population of about 10,000 people. This represents about 5.7% of the province’s total population. Though there has been little support among Spanish institutions for withdrawal from psychiatric drugs and few initiatives focused on reducing psychiatric medications generally, I have been pursuing this practice for several years now.

The main reason for supporting withdrawal, in my opinion, is for the sake and safety of the patient. In modern medicine, the concept of doing no harm is often described as “quaternary prevention,” which is defined as action taken to protect individuals from medical interventions that are likely to cause more harm than good.

A second reason is that by trying to avoid the excessive medicalization of the difficulties present in daily life, we allow a space for patients to develop a stronger sense of personal agency and autonomy. This would enhance the healing role that can be played by the local community as well as the processes of re-empowerment that are so critical to recovering from the experience of mental suffering.

In short, good mental health care should protect a person’s safety and security and provide adequate information to allow that patient to make the best decisions for his or her care.

There is also a potential benefit to society from psychiatric drug-withdrawal efforts. Unnecessary and prolonged treatments lead to chronicity, disability, and a never-ending increase in economic burden, all of which challenge the sustainability of health systems. Society should discuss and make decisions about how to reallocate resources currently spent on medical interventions that have not proven to be useful or have even been shown to be ineffective and harmful.

What Evidence Supports Current Prescribing Practices?

Although psychoactive drugs have become the main, and in many cases the only therapeutic tool to alleviate the population’s psychological malaise, their massive use by prescribing physicians is not justified or based on robust scientific evidence. Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that long-term exposure to psychiatric drugs worsens the prognosis of so-called mental disorders as well as the functionality and quality of individuals’ lives.

Some examples:

- The benzodiazepine group has been shown to be better than placebo for the relief of insomnia and anxiety, but only in the short term. Most professionals would agree that their use beyond six to eight weeks presents greater risks than benefits due to the phenomenon of tolerance, dependence, and multiple side effects, especially in the elderly population. Nevertheless, benzodiazepine use has persisted. Indeed, the prescribing of benzodiazepines has continued to increase even after the introduction of SSRIs and later on the new antipsychotics and antiepileptics, whose sedative effects were supposedly going to replace the use of the “old and dangerous benzodiazepines.”

- Neuroleptics have been demonstrated to be more effective than placebo in alleviating the anxiety accompanying psychotic experiences, but mainly only in short-term studies (12-18 months). In the longer term, there is no evidence to justify their widespread, chronic use.

- SSRIs have only been shown to be superior to placebo in short-term studies (of less than six months) and only in cases of severe depression. This “superiority” means a reduction of two to four points on the Hamilton-D scale used in clinical trials to measure depressive symptoms. This reduction may be considered statistically significant, but, given that HAM-D is a 60-point scale, it does not seem to have much clinical relevance for the patient in daily practice.

In short, there is currently not enough evidence to justify many of the prescribing practices commonly used throughout the world today, including:

- prolonged use of benzodiazepines, antidepressants, and neuroleptics

- use of polypharmacy (several drugs of the same category)

- use of supra-therapeutic doses (above the maximum approved dose for a drug)

- chronic or permanent use of drugs for relapse prevention (life-long treatments)

- the use of antiepileptic drugs and lithium as mood stabilizers

- the use of atypical drugs instead of the classic ones

- the use of antipsychotics for neuro-protection (to avoid the “neurotoxic effect” of psychotic symptoms)

- the use of antipsychotics for treating negative symptoms

Indeed, increasing evidence suggests that chronic use of psychotropic drugs not only fails to improve long-term outcomes but also increases overall morbidity and mortality as well as worsens the general functioning of people exposed to them.

My Experience with a Psychiatric Drug-Withdrawal Program

As I said, I have been working as a psychiatrist for the last five years in Toro. In addition to providing primary care services, the community provides psychosocial care, which is managed by the INTRAS foundation. The facilities here consist of a residential center, supervised homes, and a day-care center serving about 50 people diagnosed with “severe and prolonged mental illness.” The typical user profile is low income with minimal education and scarce social and familial support. Most patients have some sort of disability or dependence benefit and have no legal capacity to make decisions about their lives.

The average age of this user group is about 50 years. Many of them have required multiple admissions since their youth. On average, they have been in continuous psychiatric treatment for more than 15 years. It is common for them to be prescribed multiple drugs (combinations of several antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, benzodiazepines, and antidepressants) at doses in the highest maximum range.

In 2015, in coordination with the staff of INTRAS and the residents’ primary care doctors and nurses, I began a psychiatric drug-withdrawal program with an initial duration of five years. The objective of the program was two-fold:

- reduce spending on psychiatric drugs by 50%

- reduce the users’ exposure to psychiatric drugs by 30% as measured in daily defined dosages.

At first, the effort was aimed at reducing antidepressant and antipsychotic prescriptions. The data on drug usage was provided by the pharmacy department of the Health District Area of Zamora, which compared the community of Toro with the rest of the province of Zamora.

During 2015-2018, almost 500 people were invited to participate in the program. Three-hundred-fifty accepted (70%). The main reason for refusing to participate was fear of relapse, as well as previous negative experiences with changes in medication. In many cases, people refused to try withdrawing from their medication because they had been told they should continue their treatment forever.

Around 50 people abandoned the program because they could not tolerate the withdrawal process or decided to drop out for other reasons. The main symptoms that made the withdrawal process difficult were anxiety and insomnia, which reversed when they were put back on the drugs at a higher dose. None of the 350 people in the program needed to be admitted to the hospital as a result of withdrawal or relapse symptoms.

To achieve the objectives of the program, and after reviewing the limited literature on the subject, I was guided by the following principles:

- Always consider the possibility of not initiating unnecessary treatments (what psychiatrist Alberto Ortiz Lobo calls the indication of no intervention).

- Keep in mind the concept of quaternary prevention (avoid being harmful as far as possible).

- Upon initial use of a drug, offer a gradual decrease in medication once the patient feels he or she has recovered (between 6 and 12 months, depending on the case).

- Offer a gradual reduction in medication to people with chronic, persistent symptoms, despite–or perhaps as a consequence–of chronic treatment. When I spoke with someone from this group, I thought it was important to discuss with them the possibility that chronic persistent symptoms–depression, dysthymia, and so forth–could be due to chronic treatment with antidepressants (late dysphoria), and thus it was necessary to assess whether a dose reduction could alleviate their symptoms.

- Try to avoid polypharmacy and supra-therapeutic doses, asking the patient’s opinion about which drug and what dose he or she considers the most effective.

- Always check pharmacological interactions, especially in elderly and poly-medicated people, to guide the process of de-prescribing and/or substitution of drugs. In complex cases of multiple drugs, lack of response, or paradoxical or very striking secondary effects, I have used pharmacogenetic tests to support changes in treatment.

- Facilitate coordination with professionals, family members, and caregivers.

- Inform people, to the best of my knowledge, the balance of risks and benefits of the withdrawal process and facilitate the participation, collaboration, and cooperation of the person and of his family and caregivers in the decision-making process.

- Guarantee accessibility and establish a safety net in case of need for immediate attention by telephone, e-mail, and mobile phone.

- Establish with the user flexible and reviewable objectives in each review consultation.

- Be alert and inform the patient at the potential first signs of withdrawal or relapse.

- Gradually and progressively reduce the dose of only one drug at a time. As a guide, do not decrease more than 10% to 20% every six to eight weeks. This means that to completely stop a drug, it may take more than 12 months.

- In cases where multiple drugs are used, try to select with the patient the order for the process of dose reduction. Consider the time of exposure, the risk of withdrawal or relapse, and the patient’s experience using a particular drug.

- Ask the patient about reasons to take the drugs, his or her opinion about their utility, and preferences regarding the method of administration (tablets, solution, long-term injectables). Most people on chronic antipsychotic treatment have said they did not remember being informed about the risks and benefits of the drugs or the duration of treatment. They were also not given the opportunity to decide the method of administration. Most people asked to choose between continuing their injectable treatment or switching to tablets opted for the latter and expressed openly that they did not like the shots.

- Finally, refuse any relationship with the pharmaceutical industry that could influence my prescribing practices.

Preliminary Results (2015-2018)

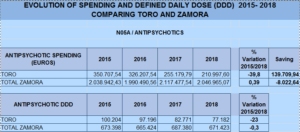

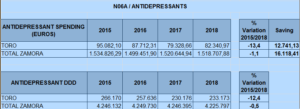

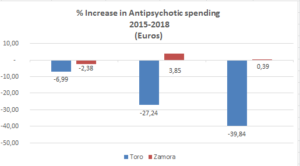

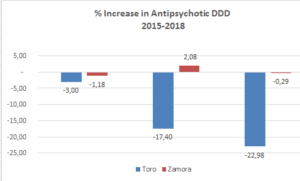

Three years after starting the drug-withdrawal program, I was able to document:

- a reduction of 40% in spending on antipsychotics

- a defined daily dose (DDD) reduction of 23% in use of antipsychotics

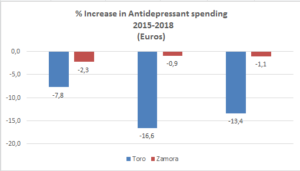

- a reduction of 13.5% in spending on antidepressants

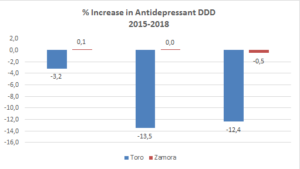

- defined DDD of 12.5% in use of antidepressants

These results are illustrated in figures 1-5, below. (Please note that the bars in figures 2-5 represent the periods 2015-2016, 2016-2017, and 2017-2018.)

The lower reduction in antidepressant expenditure, as well as the upward trend in 2015, could be explained by the introduction of new antidepressants (desvenlafaxine and vortioxetine) as well as the fact that these drugs are also prescribed by other doctors (family doctors, geriatricians, neurologists, physicians, and anesthetists in pain units).

In global terms, as a result of the drug-withdrawal program, an accumulated savings of more than 150,000 Euros has been achieved in three years. These results contrast with the trends in spending and defined daily dose in the province of Zamora, which remained stable over the same period.

Fig. 1

Fig.2 Fig.3

Fig.3

Fig.4

Fig.5

Barriers to the Drug-Withdrawal Process

I encountered various barriers, forms of resistance, and difficulties during the drug-withdrawal process:

- On a personal level, it has been quite difficult to handle the uncertainty of making decisions that could put the patient at risk of suffering from withdrawal or relapse symptoms. This is particularly so given that the medical literature on the subject is scarce and this line of work contrasts or even comes into conflict with standardized guidelines.

- Trying to do things differently can create distrust and suspicion or even generate open rejection by one’s colleagues. From a conventional point of view, only withdrawal cases that have “gone wrong” will be evident—that is, when patients are admitted to hospital. A patient admission is usually considered a failure to be avoided, is taken to meant that something has been done wrong, and thus that someone is to blame. In this context, I can be seen as responsible for the admission of any patient from my area, regardless of the reason and whether or not that patient participated in the drug discontinuation program. I could even be accused of malpractice for not joining the generally accepted guidelines and protocols.

- On the other hand, the patient and the family may also face fear and uncertainty, which in itself can be a stressor or destabilizing factor. Many people on chronic treatment have internalized the widespread reductionist notion that their problems are due to a mental illness of biological origin, and that pharmacological treatment is essential and forever. Breaking this conceptual frame can be liberating and hopeful, but it can also be very distressing.

- Finally, due to this uncertainty, any minor change in a person’s mood, thinking, or behavior tend to be attributed to the decrease of medication (even though it might be quite usual with regular drug treatment), and either the patient, the family, or other professionals would apply pressure to resume the previous drug treatment.

The preliminary objective conclusions of this study are that it is possible to decrease both spending on psychiatric drugs and patients’ chronic exposure to them, and that this can be done with no serious harm to the participants. In fact, no person in our study had to be admitted to hospital due to a dose reduction or treatment change.

My subjective assessment is that, in general, the drug-reduction process has been well-tolerated and has had good acceptance among those treated. Not surprisingly, patients have positively valued being offered a chance to participate in decision-making about their medication.

Questions for Further Discussion:

- Can a withdrawal program be of benefit for the patient?

- Can it have an economic impact on the overall efficiency of the mental-health system?

There is evidence that the use of low doses of antipsychotics, and for the shortest time necessary, may be better for the patient in terms of recovery and functionality. However, this result comes from studies of people suffering from a first psychotic episode. It is not clear whether a dose-minimization strategy would also be useful for patients on long-term treatment as is the case in this study. There are already important initiatives in progress in other countries (for example, the RADAR program of the NHS in the United Kingdom) so we will have to wait for the results.

- Is the potential damage caused by chronic psychiatric drug treatment reversible?

- For how long would it be worth trying a harm-reduction strategy?

And if we assume that it is never too late for recovery from such damage:

- Who is to define the benefit and how are we to measure it?

- How do we define and best measure symptom reduction, improvement of functionality, quality of life, personal satisfaction, recovery of family and social life, access to work, and so forth?

Regarding the economic consequences of a drug-withdrawal program, in the Spanish public health system (at least at the management level of a psychiatric service or a hospital), the reallocation of resources is not possible. Thus, the savings in pharmacy spending will not go toward investment in more staff, training, research, or new assistance programs. Most likely, the money saved on pharmaceuticals will end up simply countering the excess of pharmaceutical spending in other areas or services.

It seems illogical that the healthcare system approves and finances very expensive treatments of doubtful long-term effectiveness (and with increasing evidence of their negative impact on public health) while community and social resources remain scarce. It is also absurd that doctors have to manage a crossfire of pressures from Big Pharma on one hand (which is trying to maximize sales) and the healthcare system on the other (which has approved new drugs yet strives to contain prescription spending and promote the “rational use of medication”). Yet neither the pharmaceutical companies nor the healthcare system will encourage or support a drug-withdrawal process.

In Spain, most people with disabilities due to mental illness have very low income with which to conduct a decent life. In Toro, many subsist on only a few euros per day, just enough for coffee and tobacco. Yet they are considered “lucky” for being prescribed, often without information or consent, the latest approved drug—usually the most expensive one. That is, money goes toward drugs but not to pay for other essential psychosocial, community, and economic support.

Maybe we should ask the patients what their needs are and what they would choose to do. Thus, they could share in at least part of the savings from unnecessary or even dangerous long-term medication.

I call for zero tolerance for the mental health system and for psychiatric drugs.

NOT ONE MORE PILL!

Report comment

I agree that there should be more options for helping people in mental distress.

Professional help, included psychiatric drugs, can help some people but so can do many other approaches and I think honest information about prons and cons is the only way to help people to make their best choice.

And of course, zero tolerance for coertion.

Best wishes

Fran Sans

Report comment

Hola Francisco,

gracias por ese articulo. He visto que en España (o en Castellano) no hay mucho información sobre mermar y dejar los anti depressivos. Soy Usuario de escitalopram (mermando desde enero) y conosco la polemica por propia experencia.

Muchos gracias, Dios te bendiga.

Frans

Report comment

Thank you for this Article Dr Francisco Jose,

“They” might describe you as a “Dangerous Man”,

When I was given the option of discontinuing my Long Acting Neuroleptic Injection I “relapsed”; I attempted suicide; and I almost did commit suicide.

I decided then to carefully taper from the Neuroleptic injection with the help of oral medication. Even so, I still suffered from Extreme Anxiety, something I had never experienced before.

With luck, I was able to get a picture of how my Extreme Anxiety worked:- If I could avoid engaging with my “fearful thinking” I could eventually balance off, but it was difficult for me to ignore my “thinking” because, it seemed real.

With time, the Anxiety softened.

It took me 6 years between 1984 and 1990 to reduce from 25 mg per month of Fluphenazine Decoanate depot injection to 25 mg per day of Mellaril (- and eventually nothing). But I had returned to normal life by 1984.

Report comment

https://iahip.org/inside-out/issue-16-spring-1994/an-interview-with-prof-ivor-browne

“….Later I came back to Dublin and worked in St. John of God’s. Major tranquillisers, psychoactive and anti-psychotic drugs were just being introduced at that time. Young boys were coming up from the country diagnosed with schizophrenia, and the drugs seemed to bring them back to normal. If I had just been there a year I would have left with that impression. But by my second year nearly all of them were coming back in a worse state than before, and that raised a big question in my mind about orthodox psychiatry: that while it was removing symptoms, it wasn’t really changing people….”

Report comment

Dear Fiachra,

may be being considered a “dangerous man” is a honour after all…something is being done that puts at risk the stablishment

I guess the drug discontinuation process can be very different for each person, and in your case a very hard one. The point is that no one knows beforehand how it will run this withdrawal journey…

The most honest thing we can do is admit that we do not know a lot of things, explain the risks and try to help people for their best, avoiding unnecesary harm.

Petter Bregging would say that a warm human relationship is the best we can offer as health professionals.

Best wishes

Fran Sans

Report comment

First of all, I would like to congratulate you on your research initiative.

In addition, the absence of relapse, defined as the need for rehospitalization, is an extraordinarily good result. Especially since you have passed the period of beginning of weaning, the most at risk of relapse.

I have some reservations about the pace and the weaning order suggest to your patients.

1) I do not think that a patient who is poorly dependent on psychotropic drugs requires such a long withdrawal. The duration of weaning should be a function of the duration of exposure: the longer and the most intense is the exposure, the longer the weaning time should be.

One-day, high-dose exposure requires weaning? I think not.

An exhibition for a week? maybe two-three days.

A one-year exhibition? three or four months.

An exhibition of more than 5 years? Maybe it will take a weaning of more than one year.

But it also depends on the medication, the motivation of the person and his anxiety. It depends on his surroundings and other social conditions. Typically, you can not compare benzodiazepine dependence, whose withdrawal is torture, and dependence on Haldol, whose withdrawal is often a physical and psychological relief, despite the risk of relapse.

2) The decrease of one drug after another has the advantage of indicating, in case of withdrawal syndrome, which drug is at the cause, since you only decreases one at a time. However, this weaning order has the drawback of considerably lengthening the duration of the overall weaning, and of delaying the start of weaning of the other drugs, which continue to do damage during this time.

In addition, some drugs, in polypharmacy, have antagonistic effects. Therefore, decreasing them at the same time may be easier than decreasing them one by one (when the client is taking a sedative and a stimulant, for example).

Of course, you are anxious to cause relapse of your patients, because the rate of rehospitalization is easily measured, while the decrease in toxicity of drugs by weaning is less obvious. Have you done biological tests to your clients to check the progress of their health? Is there a control group where such tests have been done?

If this is not the case, you are missing an objective measure that could be extremely useful when exposing your results. For is the progressive suppression of drug toxicity, not one of the goals of weaning?

Regards,

Sylvain Rousselot.

Report comment

Dear Sylvain,

thank you for your nice comments and smart suggestions.

Of course I would like to have more objective measures to support the results, mainly in terms of functionality and cognitive recovery, but this has been a small and first step. Hopefully in the future, with the collaboration of more coleagues, the proyect will be more ambitious.

At present, I count with the most valuable subjective data, the opinion and narrative of the people involved.

As for the tests, I do offer physical health check up regularly that include blood test for metabolic syndrome and of course the serum levels of drugs (clozapine, lithium, valproic acid…) when necessary.

Thank you again for your inspiring comments

Fran Sans

Report comment

Hi Dr. Francisco, I read with the utmost interest your study. First of all congratulations!

The review the study has triggered in my mind the following observations/questions , which I would like to share with you and the site members:

-You stated that…. almost 500 people were invited to participate in the program. Three-hundred-fifty accepted (70%). Do you have any feedback about the main reason(s) as why 25% did not accept? This could be extremely important data to develop insight about consumer’s engagement in withdrawal practices.( It looks like you are reporting some of the reasons for about 50 participants).

– You stated that..None of the 350 people in the program needed to be admitted to the hospital as a result of withdrawal or relapse symptoms. To me this is impressive, and I feel it would be beneficial to know about what contributed to the high retention rate, high level of functioning, and stability of these consumers.

– Your cost saving figures do not include savings from prevention of episodes of inpatient care. That would be a very valuable piece of information, needless to say. Can you elaborate on that?

– Also you referred to the need to….Facilitate coordination with professionals, family members, and caregivers. Can you be more specific on how you accomplished that? This is a very important aspect without question.

– I TOTALLY AGREE WHEN YOU SAY” Maybe we should ask the patients what their needs are and what they would choose to do.. Indeed this should be common practice… Also , I would speculate that including in the process Peer Specialists, could benefit the path of withdrawal in many ways, including symptoms management, and relationship building at different levels.

Thanks you ! Marcello Maviglia,MD,MPH, Albuquerque, NM

Report comment

Dear Dr Maviglia,

thank you very much for your comments and interesting questions.

First of all I would like to clarify that I am not a resaercher, nor an academic, just a down to earth general psychiatrist, trying to do my best with the 15 minutes per patient schedule I am given; and this is not properly a resarch paper but a sort of naturalistic narrative where I try to explain my personal and local experience.

I am aware this can pose more questions than the answers I have, but somehow that was one of my purposes.

Regarding the persons that refused to participate, some of them felt fine on their medication and did not questioned that they could do as well with less or no medication at all. Others, although did suffer from persistent symptoms, did not think it was a failure of the treatment but of themselfs: they have been told that their disease was severe and resistant to treatments, but they should continue for ever even though the lack of efficiency. In other cases the families and carers were afraid to try any change…

Of course there are a lot of people for whom drugs have been or are still the best option to alleviate their mental suffering, and they have all my respect; but in my opinion, the dominant narrative of standard psychiatry (biological and reductionist) can be very invalidating and frustrating for people; they are told that they suffer from a brain condition and the main treatment are very specific psychiatric drugs (magic bullets).

As Joanna Moncrieff proposes, this “disease centered model” has not been proved, but it has gained the status of truth for professionals and patients. So, who would stop a medication that can correct the disorder, like insuline or anibiotics do? This medicalized cosmovision internalize the mental suffering and puts the responsability on the individual, minimazing the importance of social, economic and political context. From a “drug centered model”, we could use pharmacological treatments to alleviate symptoms, like painkillers or tranquilizers do, but it would be much easier to understand them just as a temporary remedy, not a necessary and ever lasting treatment.

As for the admissions due to relapse or withdrawal symptoms, I just can say that the number of admissions ahs remained steady during these 3 years; may be in the future the group of people that has been able to minimize or stop their medication will function better and will need less care and hospital admissions, but this is at present just speculation. In the work of Wunderink (2013), the group on the reduction arm had less relapses and better functioning but that was obvious after 3 years and very clear at 7 years follow up. Similar results have been found in other experiences like Soteria or Open Dialogue. In my experience, it is too soon to evidence clear benefits for the patients, apart from the satisfaction to have participated in their decision making process. I think in my case the key point has been to facilitate a colaborative and participative approach to the withdrawal process.

Finally, regarding the coordination and peer support with other profesionals, families and carers, I have to admit that sometimes it has not been easy, specially with some of the psychiatrists of my own service; but I have been very lucky to have the support of mental health nurses, psycologists, family doctors, social workers and carers. May be the key is that I work very close to the community; actually my consultation room is placed in the same building that the primary care center, and that makes easy the contact, collaboration and coordination with them.

I hope this has clarified in part some of your questions.

Kind regards,

Fran Sans

Report comment

Thanks Dr. Francisco, this is a most inspiring blog! It is very refreshing to know there are still some psychiatrists that actually care about the patient and their well-being. You deserve many accolades for your integrity and bravery in stepping outside the box of ‘standard of care’ psychiatric drugging to protect patients from the harm of dangerous drugs and give patients a voice in what they want.

Report comment

Dear Rosalee, thank you so much for your kind and supporting words. These are the sort of things that guide and give meaning to my work.

I can find information and knowledge from books, papers, and other colleagues, but real wisdom…this I just can learn thanks to the generosity of the persons that every day share with me their expertice and strenght to fight and survive mental suffering. I want to express my gratitude to all of them.

Best wishes

Report comment

Thanks for doing this important work. It might impact millions.

Report comment

Things are changing and there is no going back !!

Best Wishes

Fran Sans

Report comment

What about the Hidden + Massive Cost of Disability –

My experience and maybe most peoples experience is that the drugs Disable. Coming off and reducing the drugs opens up a completely new opportunity of return to gainful living and Massive cost saving.

Report comment

Absolutely !!

Over-medicalization is not jus a probem for the person but for the sustainability of society.

A real pulic health issue !

Thank you for your comments and best wishes

Fran Sans

Report comment

Thank you, Dr.Lacussan, for doing and highlighting this essential work. You truly are a psychiatrist, a word of Greek origin, meaning ‘healing of the soul and the mind’. Medication does serve a purpose in treating people with mental health conditions. But, it cannot stand alone and in many cases, when it has achieved a short term function (eg SSRI lifts the mood of a person with major depression to the point they can engage with psychological therapy), then it should be, but isn’t assessed for a gradual, monitored discontinuation.

I have been taking SSRIs for the last 7 years, hospitalised 4 times. If the correct assessment, diagnosis and trauma counselling had occurred at the outset, I believe I would have had a less painful path to recovery, would not have had re-hospitalisations and would not be struggling now with meds. I have had three failed discontinuation attempts, which I can now see are linked to the dose drops available to the doctor/patient. Recent article in the Lancet journal by Horowitz and Taylor provide valuable information and guidance on withdrawal from SSRIs and has stimulated more discussion from various interested parties on this topic. I applaud and thank you and all medics who are willing to think and act outside the box for the benefit of humans. Good health to you and your patients.

Report comment

Aliveagain,

Thank you so much for your kind and encouraging words and for sharing your own experience.

I totally agree with your points.

Hopefully, initatives like that of the International Institute for Psychiatric Drug Withdrawal (IIPDW), with the knowledge and wisdom of first hand expertices, will help all of us to provide a better support.

Users, survivors, insiders, first hand expertices experiences are essential to improve mental health care.

Best wishes

FRan Sans

Report comment

Thank you for such systematic work on an important issue. I think it is very telling that you refer to the nutrient deprivation and food insecurity of many of your patients (having only enough money for coffee and tobacco). In my work on nutritional treatment of mental disorders, I have encountered hundreds of people who have lessened their medication withdrawal symptoms by improving their nutrient intake (either through diet and/or broad spectrum nutrients in pill form).

Report comment

Dear Bonnie, of course there is a lot of different issues involved in drug withdrawal (family support, religious believes, physical excersise…) and I totally agree that a good nutrition is fundamental, altough sadly specific counselling in this matter is not ussually available…

Hopefully in the future nutritional assessements and treatments will be part of the standarized approach to drug withdrawal programmmes.

Thank for your support and best wishes

Fran Sans

Report comment

Thanks for this comment Fran. But I don’t think just ‘good nutrition’ is sufficient for many people. Although if that is your goal, you do not need specialized assessments: just teach people to eat whole foods, never eat processed food. By doing that you enhance nutrients, and you also reduce sodium (big problem in population for hypertension). This is how the SMILES trial resulted in 33 % remission of Major Depressive Disorder in just 12 weeks, with (of course) no side effects [https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y].

But there is an even larger body of literature of ~50 controlled trials of broad spectrum micronutrients (minerals, vitamins) and B complex that show complete resolution of symptoms in many disorders involving irritability, mood instability, explosive rage, ADHD.

Clinically, people regularly use the broad-spectrum formulas to help with withdrawal from meds, but we don’t have any controlled studies on that yet.

Report comment

“Maybe we should ask the patients what their needs are and what they would choose to do.” Absolutely. “Can a withdrawal program be of benefit for the patient?” Absolutely. Since the ADHD drugs and antidepressants can create the “bipolar” symptoms, ending the prescribing of those drug classes is likely a good idea. And since the antipsychotics/neuroleptics can create the negative symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome, as well as the positive symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via antipsychotic induced anticholinergic toxidrome. Ending the prescribing of that drug class is likely a good idea as well.

“It seems illogical that the healthcare system approves and finances very expensive treatments of doubtful long-term effectiveness (and with increasing evidence of their negative impact on public health) … Yet neither the pharmaceutical companies nor the healthcare system will encourage or support a drug-withdrawal process.” “It’s too profitable” to end psychiatry’s iatrogenic illness creation system.

Thanks for going against the grain, speaking the truth, and working to actually help people.

Report comment

Someone else, thank you for your words…that helps me to keep the meaning and guide my work.

“It’s too profitable” to end psychiatry’s iatrogenic illness creation system”.

ABsolutely !!

Kind regards

Fran Sans

Report comment

Such wonderful news! Working in private practice as a psychotherapist in southern Spain, I see the continual reality of patients who come for therapy, but who have been taking antidepressants and anti-anxiety medication, often for years, that they are given not only by psychiatrists who offer no therapy, but also by too many well-meaning and over-worked GP’s. Only very few of these patients are aware of the potential side-effects of what they so blithely swallow every day. Further, due to the effects of said medication, it is much more difficult for me to show them the way to become “autonomous”, unless they are also willing to wean themselves off their particular drug … most often benzos or SSRI’s. Obviously my recommendation is that they do so under the care of their medical doctor, but then we often run into resistance by that doctor, and unless the patient is strong-minded, that is where it ends. I know, of course, that this problem exists in many other countries, but I am continually amazed at the ease with which people here are prescribed drugs, and the alacrity with which said prescriptions are accepted. So … mil gracias por lo que haces!

Report comment

Sotoleon,

Thanks to you for exposing so well the sad situation of mental health in most places of Spain and probably many other countries.

I think that we as health professionals, have been captured by the spell and promises of biological and pharmacological psychiatry and modernist talking therapies, and we have lost the most powerfull healing skills we had: ourselves and our human relationship.

Un abrazo

Fran Sans

Report comment

Hello,doctor Fran Sans.I am a user of the mental health services in Spain. I am taking a lot of medication.I take five different pills, two antipsychotics,(abilify and risperidone),cymbalta,rivotril and akineton retard. I am having internal tremors that prevent me going out. What do you suggest me to do?

Report comment

Hola Piston, I am afraid I can’t give you a precise replay;

I think this is not the better space or place to answer personal or particular issues.

Firstly I would need to have some knowledge about you ( I don´t know you, I don’t know what happened to you, why and when did you started to take psychiatric drugs, if they have been or still are helpful, which of them do you consider helpful or harmful, do you think you need any of them, how are you doing nowdays, what familial or social support do you have, have you previous experience in trying to reduce the medication…)

I think the first step would be to have a good supportive and safe network and a trustful relationship with your health professionals (doctors, nurses, family doctors…).

Having said that, and from a theoretical point of view, I have to admitt that it seems to me you are on too many drugs and that those tremors could be a neurological side effect of one or more of your medications (achatisia, tardive dyskinesia, parkinsonism or chronic dystonia).

It seems there is not evidence to support the prescription of two antipsychotics (altough this is common practice), and in the case that this were a temporary option, I don`t consider the combination of ariprazole+risperidone the best option. May be if you could stop one of them this would help with the tremors. On the other hand, I tend to use akineton (biperideno) just for acute dystonias, not as a long term treatmente, because the cognitive disfunction it can cause among other anticholinergic side effects.

Another point would be to check accurately any pharmacological interactions with other drugs of common use, like statins for reducing cholesterol or omeprazol for gastric protection. Another very easy option to try to minimize metabolic interactions, would be to shift rivotril (clonazepam) to lorazepam, that does not interfere with the liver metabolism. Finally, I don`t know why you are taking duloxetine, but like any other antidepressant, it should not be prescribed for long periods, and it has an important risk to produce withdrawal symptoms. Another posibility would be to have a pharmacogenetic test done (Amplichip or others ) to know if you have a metabolic deficiency that makes the medication less effetive or gives you serious side effects.

I have checked the metabolic interactions of your treatment and it seems a priory that the metabolic liver path 2D6 is saturated, which means that some drugs are interacting with others and this could affect the efficacy of your treatment.

I am sorry for all this technical talking, but in summary my advice would be: try just one antipsychotic (if still necessary), stop Akineton (biperiden), try to discontinue antidepressants if you are not feeling depressed and shift clonazepam (rivotril) to lorazepam.

Of course this is only a theoretical hypotesis and you have to keep in mind the serious risk of relaps or withdrawal symptoms, so, again, please, get in contact with your psychiatrist to discuss all these issues.

Best wishes

Fran Sans

Report comment

Hello,Dr.Francisco Javier Sans. First of I want to give you my thanks for taking your time and your extensive reply and what do you think is a possible solution to the health problems I am suffering. I agree with you this is not the best place to discuss. I want to say the two diagnostics I have.I have been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia in 2008 and OCD and esquizotipico disorder in 2009. I haven´t been in a hospital hospitalized since 2009. I take the same treatment as I take when I was discharged from the hospital. If I could contact you in any form (email or social network). I would like to be treated by you or a friend of you who has the knowledge how to withdraw psychiatric drugs very slowly. I live in Galicia.

I agree with you that taking two antipsychotics is not beneficial when they work on the same gaba receptors,plus the problems they can cause to liver. I was giving biperideno to control the tremors I was having when they put me on abilify,risperdal,cymbalta,clonazepam.I have cognition problems too. I don´t remember what I read. In addition, I think I have a movement disorder either tardive dyskinesia,akathisia or dystonia. I have too pace sometimes and I have contortion movement in my back plus the inner tremors. Did you do a interaction drugs checker? Can I check for vitamins if I am lower on them,plus minerals like magnesium? I dont know what the amplichip is. I would like to taper the abilify. I think it is the one is causing the internal tremors.

Thank you very much,

Piston

Report comment

Sure, Piston.

I will try to find a colleague in Galicia willing to help you.

In the meantime, we can keep in touch via linkedin or if you prefer through my official e-mail: [email protected]

Kind regards

Fran Sans

Report comment

Thank you,doctor.I will email you.

Report comment

Hello,Doctor Francisco Javier Sans.Sorry to bother you again.I sent you an email to [email protected] from my hotmail account with subject:…….piston:psychiatric drug withdrawal in Spain.

Thank you,

Pistón

Did you receive it?

Report comment