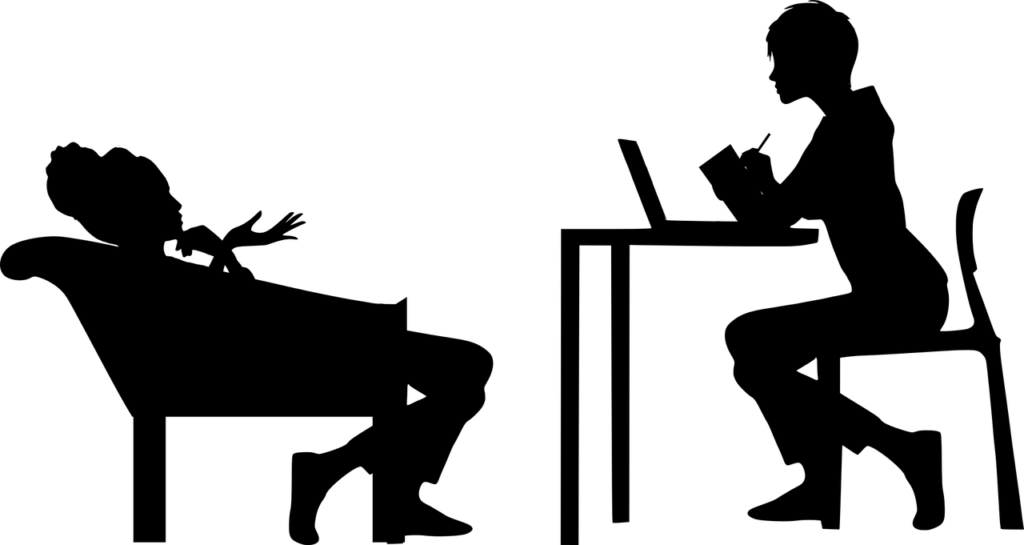

A new systematic review of the literature provides insight into why it is that some therapists tend to be more effective than others. Using a narrative approach, researchers Erkki Heinonen and Helen Nissen-Lie found that successful therapists have professionally cultivated specific skills—such as empathy, communication skills, and the capacity to form and repair successful relationships—but that these skills have roots in therapists’ personal lives and attachment histories. Their findings were recently published in the Psychotherapy Research journal.

“Psychotherapists are known to differ in their effectiveness,” the researchers write. “The present challenge is to provide content to this observation: What are the characteristics of the psychotherapist that actually contribute to these differences?”

Research has found that some therapists consistently achieve better therapy outcomes than others. This effect has been convincingly established within the literature. The idea that therapist characteristics influence therapy outcomes is referred to as “therapist effects” because they are not explained by other variables, such as client characteristics and presenting problems, therapeutic approach, manualized vs. nonmanualized therapy, and random error. Therefore, although contextual and client factors likely influence therapists, effective therapists are bringing something unique into the room.

Heinonen and Nissen-Lie conducted a systematic review to determine what it is about some therapists that lead to better or worse therapy outcomes. They write:

“A pressing task is, therefore, to understand the more or less stable characteristics of therapists that explain their differences in outcome. Besides helping to understand better how psychotherapy works, knowledge on the characteristics of effective therapists would have much other practical value.”

A better understanding of therapist effects, they point out could aid the process of selecting and training therapists. This depends upon whether therapist characteristics are innate dispositions or developmentally acquired, they write. Nevertheless, merely being aware of their contributions toward effective therapy may allow therapists to engage these aspects with greater intentionality and focus.

In this systematic review, studies published since the year 2000 were included, which examined both professional and personal characteristics of therapists. Professional characteristics are qualities that the therapist has explicitly developed toward their role as a therapist, such as their therapeutic philosophy and specific relational skills designed to work with clients.

Personal characteristics describe therapists in their non-professional lives, for instance, cultural orientation, personal values, and attachment style. Prior research has indicated that specific therapist characteristics—such as gender, particular profession, and competence and adherence to treatment manual—are not likely to be determining factors.

Heinonen and Nissen-Lie clarify the study’s aim to ultimately gain a clearer understanding of what it is that therapists contribute to therapeutic change:

“The aim here was to identify the skills, traits, and qualities that more effective therapists initially bring to each of their therapy sessions independent of the interaction with particular patients.”

Their overall goal was to “identify similarities and differences in therapist qualities conducive to better outcomes.” In this process, outcomes were measured by clients’ functioning and wellbeing after therapy or in follow up assessments.

The studies included in this review featured diverse methodologies, tools, and analytic procedures, which made conducting a quantitative analysis infeasible. Therefore, the researchers chose to utilize a narrative approach to synthesize findings across the 31 studies. Moreover, they took a critical approach to their interpretation of studies, choosing to emphasize results from ones that employed higher quality approaches and rigor.

The results of their synthesis indicate that therapists’ professional characteristics (e.g., philosophy, values, and attitudes about treatment) more directly influenced therapy outcome. However, personal characteristics, including personal values, attachment style, and descriptions of therapists’ non-professional lives interacted with the therapeutic work and the client-therapist relationship, even if they were not observed to influence the outcome directly.

Regarding therapists’ professional characteristics, some findings suggested that in long-term psychodynamic therapies, the therapists’ belief in insight and kindness as curative factors led to better outcomes. Additionally, in shorter-term treatments, when experienced therapists were confident in their professional skills, they had better results with clients.

However, in longer-term therapies, the therapist’s confidence could lead to worse outcomes, particularly with very distressed clients. In these instances, “professional self-doubt” was seen to be beneficial. For example, more effective therapists reported making more mistakes in therapy than less effective ones.

Therapists professional interpersonal skills were more predictive of outcome than therapists’ self-ratings of their occupational self-efficacy and confidence. The ability to professionally relate to clients with empathy, warmth, positive regard, clear and positive communication and the capacity to take critical feedback predicted better outcomes across all levels of therapist expertise.

Interestingly, the findings suggested that it may take an interpersonally challenging situation to arise in therapy for these therapist effects to emerge. In other words, how therapists respond when faced with challenging moments differentiate the effective therapists, who respond with empathy, self-control, and emotional containment, from the less effective ones.

Therapists’ personal attributes were not directly tied to their therapy outcomes, as with the therapists’ professional factors. For example, the influence of therapists’ attachment style and experiences of parental bonding on client outcome was not clearly detectable. However, even if these factors do not impact the outcome directly, they may still affect the outcome by interacting with other therapy ingredients, such as the client-therapist relationship. Moreover, it is difficult to sever aspects of therapists’ professional and personal lives, particularly when examining relational skills.

Although the findings did not indicate pronounced effects of therapists’ private intrapersonal and interpersonal lives, some patterns suggested that effective levels of therapist humility and self-doubt were related to their ability to be nurturing toward themselves (i.e., an intrapersonal aspect). This ability fostered a productive amount of self-doubt that in turn, led to better therapy outcome.

This may be because therapists’ personal, positive coping/psychological resources helped them to focus on the client and maintain greater flexibility. In some studies, personal qualities, such as mindfulness, “emotional intelligence,” and “reflective functioning,” compensated for therapists’ psychological vulnerabilities and bolstered outcome. Indeed, although the therapists’ attachment style was not distinctly related to outcome, one study found that therapists’ who were identified as securely attached were more effective in work with severely distressed clients.

More importantly, however, it appears that therapists’ capacity to access their own positive supports and psychological resources could compensate for vulnerabilities (e.g., the effects of weaker attachment bonds), enabling them to better differentiate between self and client. Therefore, therapists’ ability to exercise self-control, self-insight, and manage countertransference was deemed important, even if these aspects do not serve as direct measures of outcome.

After exploring the complexity of these findings, and the difficulty in distinguishing between therapists’ professional and personal presentations, the researchers noted how findings “point to the complexity of how therapists interact as professionals and people overall with the numerous variables linked to the outcome and contraindicate the study of therapists in a ‘vacuum.’”

As Heinonen and Nissen-Lie review study limitations, they note that these results reflect therapists’ traits rather than states. In other words, situational factors (e.g., illness in family, poor workplace environment) are not captured in this systematic review.

Overall, the professional skills exhibited by effective therapists, although developed and refined within a professional capacity, are considered to be connected to their personal lives and attachment. The researchers highlight several findings that underscore how “therapists’ self-rated skillfulness, difficulties in practice, and coping mechanisms, and attitudes toward therapy matter.”

There were no salient effects related to “personality style” (i.e., the Big Five traits), but basic relational skills around warmth were essential. Furthermore, the ability to stay focused on the client and manage reactions, capabilities that are connected to a secure attachment style, were influential.

Heinonen and Nissen-Lie conclude:

“According to the consistent findings of this review, more effective therapists are characterized by interpersonal capacities that are professionally cultivated but likely rooted in their personal lives and attachment histories—such as empathy, verbal and nonverbal communication skills and capacity to form and repair alliances—especially with interpersonally challenging clients.”

****

Erkki Heinonen & Helene A. Nissen-Lie (2019): The professional and personal characteristics of effective psychotherapists: a systematic review, Psychotherapy Research, DOI: 10.1080/10503307.2019.1620366 (Link)

“Interestingly, the findings suggested that it may take an interpersonally challenging situation to arise in therapy for these therapist effects to emerge.”

Given the reality that today, “the prevalence of childhood trauma exposure within borderline personality disorder patients has been evidenced to be as high as 92% (Yen et al., 2002). Within individuals diagnosed with psychotic or affective disorders, it reaches 82% (Larsson et al., 2012).”

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

And the fact that NO “mental health” worker may EVER bill ANY insurance company for EVER helping ANY child abuse survivor EVER, unless they first misdiagnose them with one of the billable DSM disorders.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-child-does-not-have-bipolar-disorder/201402/dsm-5-and-child-neglect-and-abuse-1

And taking into account the history of child abuse covering up crimes by the psychological profession.

https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/01/23/18820633.php?fbclid=IwAR2-cgZPcEvbz7yFqMuUwneIuaqGleGiOzackY4N2sPeVXolwmEga5iKxdo

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Freudian_Coverup

It appears the majority of therapists are faced with an “interpersonally challenging situation.” Oh no, I can’t bill to help any child abuse survivor ever. So most therapists tend to choose to misdiagnose child abuse survivors, with the “invalid” DSM disorders, and have the psychiatrists neurotoxic poison them, rather than trying to actually help them.

Today’s scientific fraud based DSM “mental health system,” is primarily a child rape denying, covering up, and profiteering system.

For goodness sakes, we’re now living in a society where, when you report to the police that medical evidence of the abuse of your child was handed over. Rather than making a police report, and investigating. That concerned mother is told by the police to “talk to a psychiatrist” instead. It’s obnoxious. All you child rape covering up “mental health” lunatics should be ashamed of yourselves and your child rape covering up “professions.”

Report comment

Dear Someone Else. ASHAMED indeed.

Report comment

It’s really impossible to measure such a thing as “an effective therapist” because it is going to be an individual thing, how the client feels about their therapy and how they’ve been able to apply it and feel supported in that process. It is all 100% subjective and involves many moving parts.

Success in healing is on the part of the client, not the clinician. When a clinician claims “victory” rather than attributing it to the client’s work, that would be supreme arrogance, the essence of it, and basically, stealing the client’s light, which happens quite a bit. Therapists are prone to bragging about how much they help their clients, I heard it all the time during graduate school, and there are countless books to fit this description. To their mind, it’s about them and their “brilliance,” rather than being about the client and their courage, strength, and creativity. It’s why I warn of vampirism in this field.

The therapists I’ve known do not “countertransfer” as much as they, in fact, initiate the “transference.” Seems to be the state of mind before a client even walks into their office. In their minds, they seemed to want to parent me, which felt, well…gross is really what best describes that feeling.

I find it to be incredibly unprofessional, unethical and devoid of boundaries, not to mention extremely dangerous in the dependency which this creates. And yet, this is how it is taught in graduate school. This is the program.

When I was seeing pscyhotherapists, I never, ever considered them to be any kind of authority/parental figure (or even a “best friend” for that matter), but more of a provider of professional services to help me discover the aspects of myself which were causing me trouble in life, so that I could make informed changes. Most of them (all but one of them) were way out of bounds in their projections, and hated to be told they were “wrong.” That would always get turned around into a really bad manipulation and nasty projections.

I woke up to this after having spent several years in therapy, only to become more and more confused and mind-chatty, eventually down the rabbit hole of chronic rumination and endless thought loops. It was only when I stopped “talk therapy” that my mind was able to finally quiet down and focus on what I was creating in life. It was like having a nervous sytem transplant, everything just calmed down and I felt stillness and light for the first time, and I was able to ground in the present. That is inner peace, which I can’t even imagine any kind of “talk therapy” achieving, quite the contrary. For me, at least, this is the case, some may find this useful. There’s only so much blah blah blah I can take. A calm, quiet mind is a gift and it has to be cultivated and practiced.

Report comment

Your ideas, experiences, and conclusions rhyme with mine.

I wish there were more people who think like you in this world.

Vampirism and hubris define the profession, imho.

Report comment

This is an interesting finding. One of my favorite people, who happens to be a former therapist, has expressed very similar thoughts about what makes an effective therapist.

“Interestingly, the findings suggested that it may take an interpersonally challenging situation to arise in therapy for these therapist effects to emerge. In other words, how therapists respond when faced with challenging moments differentiate the effective therapists, who respond with empathy, self-control, and emotional containment, from the less effective ones.”

This concept of navigating conflict is especially one we’ve explored as friends, with us both believing that real trust isn’t built until you’ve successfully navigated a conflict (or several).

My personal view on the manualized therapies is that they are basically useless in helping the client create permanent improvements in their living situation – they focus on coping skills and changing the patient, who may very well be having a totally normal and expected response to adverse circumstances. An effective therapist, in my view, will help the client create change in their circumstances that are leading to distress. That doesn’t always come quickly. Of course, if the client is nothing more than a source of income for the therapist, marginal (or short-lived) results can be expected. There must be some level of real attachment and caring for the client.

Timely piece!

Report comment

William Glasser’s “Choice Theory/Reality Therapy” encouraged people to make helpful changes in their outward circumstances as well.

For example, finding a new job or starting to date again or calling your mother regularly.

Some outward things can’t be immediately changed. So these must be coped with.

I love the AA “Serenity Prayer.”

Report comment

There’s nothing wrong with learning new ways of being in the world as one matures and heals, alongside receiving the assistance one needs to survive.

My disdain for the manualized therapies is precisely that they rely upon learning coping skills but don’t help the individual make the changes necessary – changes that often entail long-term support and financial assistance. I didn’t need a psychotherapist or medication. I needed help escaping from an extremely abusive spouse, a proper education, and antibiotics to treat the symptoms of what I now know was Lyme disease. No one should ever be forced to “cope” with abuse or a treatable illness.

Coping skills have their place, but almost all of what the helping professions offer is medications combined with coping skills, when what most people need the most is a restoration of the social contract. This boils down to a lack of public will to help poor people. Welfare assistance and paid college/daycare would have been a much cheaper investment for the taxpayer than the fifteen year long disability path I ended up being forced into.

I have no problem with learning how to cope with life’s natural sadnesses and difficulties – they are fodder for building one’s inner fortitude and grit. Much of modern life stressors are very far removed from anything natural, and are imposed by a sociopathic capitalist class system in which there are few winners and many losers.

Report comment

Dear Kindredspirit. You say it so well when you say, “What is needed is restoration of the social contract”. If only more professionals knew what you know.

Report comment

“real trust isn’t built until you’ve successfully navigated a conflict (or several).”

That’s a good point, KS. Any relationship is going to inevitably bring some kind of disagreement or clash in values or perspectives. How that is handled is key to the substance and creative power of that relationship.

I’m not sure I’d go so far as to say “several,” however, I can always tell after one conflict if the relationship is worth it or not. If the conflict leads to a dialogue with the intention of bringing mutual clarity (whether or not new harmony is achieved or agreeing to disagree), then that is a powerful relationship and there is potential for co-creating forward.

However, if the conflict is based on power struggle and “needing to be right” and “needing to win,” and all that ego stuff, then that usually gets pretty nasty and sabotaging and I’d predict a tumultuous and mutually draining and frustrating relationship from that, no thanks.

And of course, in my experience, mh clinicians have always fallen into the latter category, which is why I detest the field. It is a waste of time and energy because that particular conflict will NEVER be resolved, and will only repeat and repeat, guaranteed, until there will eventually be “a bad breakup” or abandonment or some such sabotage. In that case, I’d say it is best to wake up, cut one’s losses, take any lessons, and move on to better things.

Report comment

Hi Alex, I tend to view conflict as a normal part of all relationships, not just something that happens once or twice and then you get on swimmingly from then on. I don’t think I’d say I can judge someone from a single conflict, though a BIG conflict early on would certainly make me hesitate to invest deeper trust in the other person. I think trust is gained in stages, therefore, after one has learned that the other person can communicate and behave in validating and nonabusive ways. I also believe that this requires any potential therapist to have the capacity to absorb some client issues early on while building that trust and while the client is learning that the enrvionment is a safe one where issues and feelings can be expressed honestly.

The problem with the mh industry and notions of conflict with a treatment provider is that most of mental health is delivered in an authoritarian manner (FYOG, as some say) rather than with truly shared and guided decision making. With the former, it’s not ever really possible for the client/provider team to build authentic trust and navigate conflict because the provider will always win any power struggle. The latter requires building trust between strangers and I think the normal rules of learning how to interact with different kinds of people applies. My comment about learning to navigate conflict was made under the assumption that the provider is acting as a helper/guide/assistant rather than as an authority but from my own experience I know that is rare, so your point is taken. The fact remains that the system of help is pretty broke.

Report comment

Yes to all of it, KS, you’re speaking truth, I believe. I’m just saying that some relationships are worth going through conflict while others, I believe, would be a waste of time and energy. For me, that would depend on how that first conflict plays out. I know there are some things I cannot tolerate right off the bat, despite the role I am playing in the relationship, and these red flags can become apparent quickly in conflict. While the nature of what we are willing or not willing to tolerate is individual, of course, I do believe we all have our need for boundaries here, for the sake of self-caring.

And at the same time, we do have opportunities to grow here, when we are challenged by conflict, and clients can give therapists the opportunity to do just this. If both parties are healing and growing, then it will not be a power-based relationship, but more of a sound healing contract, and wonderful growth can be expected on both sides. Which to me, is the point of healing through dialogue. It’s never one-sided, realistically speaking.

But, indeed, when it is this authoritarian power-struggle fyog it’s-you-not-me thing we’ve got going on, that’s purely farce, no one is healing, and it is particularly detrimental to the client, to the point of potentially causing them quite a bit of harm. Unfortunately, this is the mh industry norm.

Report comment

“I’m just saying that some relationships are worth going through conflict while others, I believe, would be a waste of time and energy.”

We’re definitely on the same page, Alex. Totally agree with all the rest, too. 🙂

Report comment

Dear Alex. So very well said. You said it better than I ever could. Thanks.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

Don’t want to be supporting psychotherapy, effective or not.

Report comment

Right, PD! One mustn’t ever support something that’s effective while fighting the ineffective stuff! Litigation is the one, true way to help people!*

*Cause the courts have such a long history of protecting children’s, women’s, indigenous, Black, Hispanic, immigrant’s, queer, urban, rural, impoverished and other disaffected communities’ civil and human rights…

Report comment

This is sarcasm, yes?

Report comment

First you need to define what you mean by “psychotherapy,” PD. Good luck with that.

Report comment

Therapy is in part just a set of skills and tools that can be taught to people to aid with distress tolerance. some people will always seek the tools, and tools can be useful. Call it whatever you want but the human need to seek help from one another will not be going away… it is the expert that needs to go away…

Thank you for speaking so eloquently to this important intersection…

Report comment

Dear Teresa: Yes we should all encourage the so-called expert to go FAR “away”.

Report comment

Interestingly it has been proven that a therapist’s personal philosophy/experiences in CBT or any other therapy is more important than their training, no matter what school they attended.

Report comment