A new article, published in Transcultural Psychiatry, examines the practice of dang-ki healing, an indigenous form of healing practiced in Singapore. The authors Boon-Ooi Lee of Nanyang Technological University and Laurence Kirmayer of McGill University draw on a decade’s worth of ethnographic research to explore the transformation of self in this practice and its applications to mental health work and psychiatry.

Dang-Ki healing is defined as a form of Chinese spirit mediumship where a deity possesses a human (called the dang-ki) who then helps others in the community with their problems. The problems range from physical illnesses to interpersonal conflicts. The authors find that a dang-ki can provide support to the client, while at the same time, their conflicts and suffering are healed in the possession process. They write:

“In dang-ki healing, then, it is not just the clients who are transformed, but also the community, the practitioners, and the possessing deities.”

As the bio-medical model of ‘mental illness’ has come under increasing global scrutiny, and alternative models of care and traditional healing practices are being explored. This increased scrutiny follows accusations of industry influence, questions about treatment efficacy, and concerns that Western psychiatric models neglect the socio-political causes of mental distress. Researchers have also noted that these Western models of care can often increase stigma and perceptions of dangerousness of the patient and that anti-stigma campaigns based on these models have backfired.

Additional concerns have been raised about the generalizability of psychological research as the majority of it is conducted on Western, Education, Industrial, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) countries, and then applied globally. Others have argued that the assumptions made in psychological research about what constitutes distress, symptoms, and health are grounded in Western values, and thus not universal.

As a result, there has been a growth of interest in indigenous models of care, which are grounded in local realities, meanings, and contexts. Often these alternative models are rooted in anti-colonial values as they cater to people whose cultures and lives have been decimated by exploitative colonial practices. Examples of integrated indigenous approaches to mental health have occurred in the Maori community in New Zealand and with Native American people in the US. These movements often focus on appreciation of service user experience, both in terms of how they understand their distress and what they consider is helpful. A recent systematic review argued that the biomedical model and traditional healthcare systems could co-exist and even benefit from each other.

The authors begin the article by noting that while various schools of psychology might have different conceptions of health and disease, they still adhere to the idea of the self as autonomous and self-contained. This, in turn, influences how the field conceptualizes disorders and treatment. This idea of the self as independent and separate does not translate to many other cultures, where the self is experienced through social relationships. Thus, Western forms of psychotherapy, which often focus on internal actualization and growth, do not translate to other places.

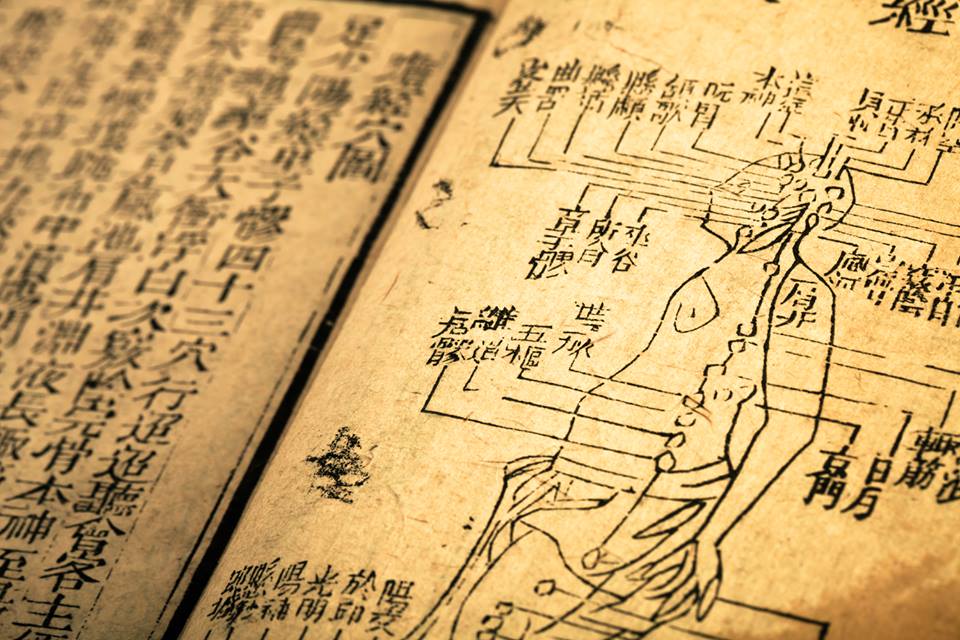

The authors use ethnographic data, participant observation, and psychological assessments of over 15 practitioners and 150 clients to explore the practice of dang-ki healing. They describe this practice as “a type of Chinese spirit mediumship practiced in Singapore and other Asian societies. This practice is based on the belief that a deity can possess a human (call dang-ki) in order to offer help to people.”

The authors aim to compare this healing practice with psychotherapy, and explore how it brings a transformation to the “sense of self, interiority, and social relationships of both practitioner and client.”

There are numerous reasons why clients (devotees) seek the help of a dang-ki. These range from experiencing ill health to seeking ritual blessings, fortune-telling, and resolving problems with career, wealth, and other relational issues. Based on Chinese cultural notions and Confucian philosophy, dang-ki promotes the idea that physical health is closely interconnected with interpersonal and social conflicts and emotional problems. Additionally, moral deficiencies, like greed and arrogance, are considered forms of illnesses. Dang-ki healing caters to all of these issues.

Deities (through the dang-ki) may help the client by offering advice or recommending talismans; they might prescribe rituals to banish evil spirits and bad luck or provide other forms of treatment like acupuncture and herbs. In these circumstances, the clients and community believe the dang-ki is not the person, but instead the deity.

The personal characteristics of these deities affect how the clients experience their presence and respond to their help. This is important because the authors conceptualize dang-ki healing as a type of embodied relational psychotherapy. Healing is more than symptom removal and disease cure. The focus is on restoring bodily, emotional, relational, and spiritual health, which could mean that the person remains symptomatic, but is at the same time able to function in relationships and contribute to daily activities.

The interaction between the dang-ki and the client is in a semi-public space like a temple. These forms of communal healing, the authors suggest, often help by including the family and community in the healing process. This is vastly different from many Western models of care where the family is often considered pathology-inducing, and the patient is isolated in psychiatric wards.

Clients often come early and stay after their healing rituals to interact with each other and share their stories of distress and healing. Unlike the therapist, the dang-ki regularly meets the clients before the official interaction. These differences point to the communalistic ethics of Asian societies as opposed to the individualistic priorities, such as boundaries and confidentiality of Western ones. In the past, many feminist therapists have criticized such ethics around boundaries and confidentiality, calling them unsustainable for marginalized communities.

Often the dang-ki will give advice congruent with cultural values of maintaining familial and community peace and having control over emotions. For example, they could say “Take things easy” or “Enjoy life” or “Don’t think too much.” Western values such as assertiveness and confrontation, often reflected in the priorities of psychotherapy, can create further relational conflict.

Other methods of healing include burning of fu (talismans with magical writing on them), which is then carried, consumed, or kept with the client. Considering this to be a direct connection with the deity, many clients report feeling calmer, protected, experience a change in negative attitudes, and an improvement in interpersonal relationships.

Lee and Kirmayer note that the practice of dang-ki healing is also beneficial to the dang-kis themselves, who might be going through their own emotional conflicts. The entry into mediumship can often be fraught with distress, but once initiated, they are considered as relatively healthy people who might still be struggling with forms of distress.

The process of being a dang-ki is considered therapeutic. In one case, the authors write about a dang-ki who exhibited depressive, anxiety, and hallucinatory symptoms, but the practice of mediumship allowed him to change his attitudes about these symptoms. This led to normal daily functioning and feelings of health and well-being. Another dang-ki reported being able to calm the uncontrollable anger which had plagued him earlier in life. Internalizing the deity’s qualities like compassion and composure can often be therapeutic.

The absence of strong individual boundaries can mean that mediums experience the pain of their clients, and the boundaries between human and deity are also porous. People who live exemplary lives through good moral conduct and noble character can be deified after death. The newer deities might have higher deities as mentors, and the former can achieve higher spiritual levels as they provide help and healing to other sentient beings.

Thus, the practice of dang-ki healing is a process of embodied transformation of the client, the dang-ki, and the deity themselves – not to forget the community that is also participating in this process. In conclusion, the authors write:

“In embodying the deities, the dang-kis become intermediaries for their virtuous actions, which provide clients with new ways of interpreting and acting in everyday social situations based on traditional Chinese teaching.”

This form and practice of healing is based in a communal environment, involves embodied healing, and encourages a reciprocal relationship between the client, the deity, and the dang-ki. It is vastly different from many Western forms of therapy where the individualistic priorities and a boundaried sense of self are valued.

****

Lee, B. & Kirmayer, L.J. (2019). Dang-Ki healing: An embodied relational healing practice in Singapore. Transcultural Psychiatry. Published online: July 1, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461519858448 (Link)

Thank you Ayurdhi.

I am glad there is a Canadian researcher involved, though

I do not think any of our authority figures on our minds will

anytime soon be possessed by dang-ki.

We have to keep the idea of mental distress being a mental disorder or illness alive and well, as it has helped the business of all medical people, even old aged homes, a great deal.

There are a few trying, yet most always still overwriting narratives. Most unfortunate that the authority keeps destroying.

It is a travesty, not even knowing how many lives have been destroyed. I think of all the young lives, the teens, snagged early, in the guise of prevention.

Report comment

In general, it’s better to adopt experience from India than Singapore.

Report comment

“Western, Education, Industrial, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD)”, I had to laugh at that one.

Weird does have a supernatural root, like Dang Ki, I suppose.

The “spiritual” infestation of Weird Psychiatry is in the form of chemicals, a sort of demonic possession.

Report comment

Eighteen years ago, and as a Christian, I questioned the meaning of a dream about being “moved by the Holy Spirit.” This dream query resulted in a “mental health” misdiagnosis.

I did escape the Holy Spirit blaspheming “mental health” lunatics. And I am still “moved by the Holy Spirit,” which is not remotely bothersome to me. That dream just meant God wanted to move me, it’s very similar to a mediumship.

But that insane “mental health” experience, and many years of research, did teach me that belief in the God of the Holy Bible or belief in the Spiritual realm is apparently against the law for the DSM “bible” thumpers.

So I find it odd, given the “mental health” workers’ systemic rejection of the Christian/Jewish Holy Spirit, that you’re now pretending that you support mediumship by Chinese deities?

The insanity, and staggering hypocrisy, of the “mental health” workers just continues to grow, and become uglier and uglier. I picture the “mental health” workers as Dorian Grey, and see the picture of them becoming more satanic and hypocritical as time progresses.

Report comment