Alcohol and the East Coast

After the civil war, immigration was opened to people who lived outside of the usual areas of Europe, in order to supplement an already thinned out workforce. Between 1870 and 1900, over 3 million immigrants arrived on America’s East Coast from Southern (e.g., Italy, Spain, Portugal) and Eastern Europe (e.g., Slovenia, Greece, Russia). They helped to fill out many of the cities along the Eastern Seaboard, including Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore.

Many of these immigrants came from cultures steeped in Roman Catholicism, Judaism, and Greek Orthodoxy. As part of family gatherings and religious ceremonies, members of these cultures were taught that alcohol, when used in moderation, can be something to celebrate in and of itself. To this day, southern France and Northern Italy are famous for their creation and expansion of “viticulture.” The idea that alcohol could be used in moderation, and even celebrated (!), was disturbing and dumbfounding to the Temperance Movement.

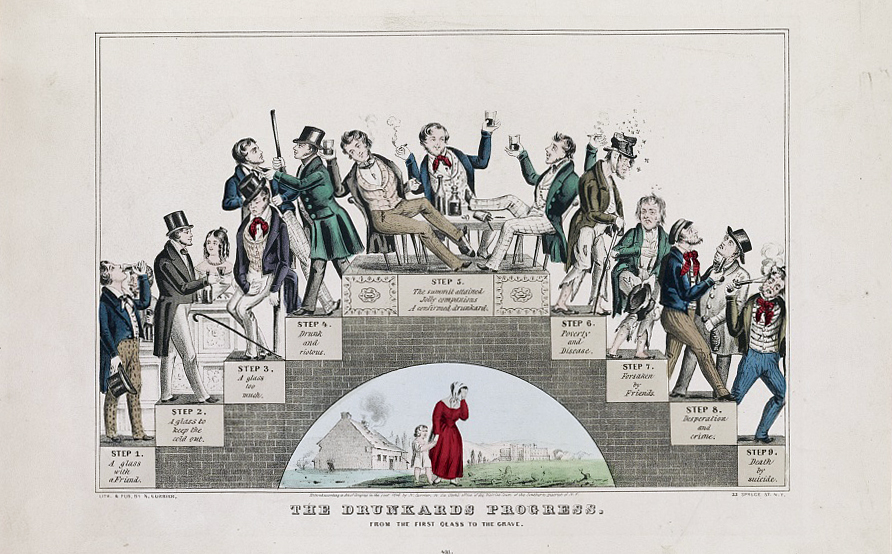

In response to the growing number of immigrants coming from cultures which included moderate use of alcohol, the Women’s Christian Temperance Movement (WCTU) decided to start an education campaign. Members of this group, which had started in 1874 around Cleveland, Ohio, invoked the spirit of Benjamin Rush by visiting immigrant communities and teaching them about the ills of drinking. How any drinker would eventually fall into the spiral of addiction. How, no matter what, the “drunkard’s progress” would lead to poverty, disease, and suicide:

As Gabriele Glaser describes in her book “Her Best Kept Secret,” the members of the WCTU were not native to the cities and communities where they were proselytizing. Most temperance and revivalist movements were stood-up in the western, more rural, areas of the country. In a fashion that will be repeated throughout America’s history with psychoactive drugs, temperance became an attempt by the WASP-y areas of the country to influence the experiences of immigrant communities settling in urban areas.

This meant that people who were targeted by the education campaigns, designed to tell the story of how alcohol was endogenously addictive, had been around moderate drinkers their whole lives. They had seen their grandparents and parents drinking at Communion and at Seders and even wedding celebrations, and nothing of the sort happened to them. In short, they were not buying it. So how did the WCTU respond? They decided to reach out to their children.

The WCTU recruited a large contingent of schoolteachers into its membership. This paralleled the Temperance Movement lobbyists’ efforts to push congress into forcing public schools to teach Temperance ideals within any “health and hygiene” classes. After teaching the ideals, the teachers would get their students to sign pledges of “Total Abstinence” from alcohol; a move which would be applied by today’s abstinence only movements regarding drugs and sexual education. The large “T” of the pledge would give rise to the term “teetotaler,” meaning anyone who chose to purposefully not imbibe alcohol.

In some ways, this is reminiscent of the what had been done to native American children, who were forced into “schools” which undertook the task of “assimilating” native children into white culture. This included cutting children’s hair without parental permission, banning the speaking of native languages, and punishment for practicing native religions. All of this was done because of the belief that native culture was inferior to white culture: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” was the motto.

Likewise, White protestant culture was seen as superior to the cultures brought in by Southern and Eastern Europeans. As Temperance was solidifying itself within white protestant culture, and since most Southern and Eastern European immigrants were not yet seen as white, this white supremacy helped fuel the work to oppress these immigrant’s culture.

The manipulation of immigrant cultures eventually grew beyond the school rooms and revival tents. A Venn diagram of leaders of the Temperance and Suffragette Movement is a near circle. Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Amelia Bloomer, and the unbending Carry Nation all worked across Temperance and Suffragist groups. When women were on the cusp of gaining the vote in 1919, incumbent politicians needed to back legislation that spoke to the concerns of white women.

These groups’ original primary social justice goal was abolition, and since slavery had been banned after the Civil War (put a pin in that, we’ll come back to it in the 20th century) Temperance had taken over as the primary legislative concern of women’s advocacy groups. Due to this brand new block of special interest voters becoming enfranchised, the prohibition of alcohol became a top legislative priority for many members of congress.

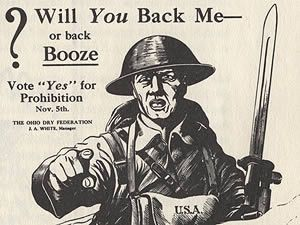

In 1919, the 18th amendment (Prohibition) was passed by its 36th state, Nebraska, becoming the law of the land. This occurred just one year prior to the 19th amendment, which gives women the right to vote. However, to pass congress, Prohibition still needed the backing of male and non-temperance voters. In order to achieve this, it was connected to the “Great War” effort, and inserted into pro-troop and anti-Germanic propaganda.

While popular with many protestant women voters, it had been difficult to pass the legislation without directly connecting booze to feared cultures and communities. Unfortunately, this is a theme that would be mirrored on the other side of the nation.

Opium and the West Coast

In the 1800s, the largest corporation in the world was owned by the British: the East India Trading Company (EITC). One of its most profitable ventures was the Opium trade. The company was able to grow opium (poppies) in India, and then process and sell the opium at a very large profit to India’s neighbors in China.

After nearly 40 years of the drug working its way into their culture, the Chinese government started to push back against the opium trade. In 1849, Chinese statesman Lin Xexu decided to prohibit and destroy stores of the EITC’s opium. In response, the British and French went to war with China in 1840, bombing and invading coastal cities and surrounding islands. This was the beginning of the first Opium War.

The first war ended in 1841, and the British gained the territory of Hong Kong in the process. Nonetheless, China did not fully adhere to the stipulations in the treaty, including not fully expanding the opium markets. Moreover, Britain had developed a lustful addiction to tea, leading to a tea versus opium trade deficit.

On top of all this, China had an equally political and religious version of the Temperance/Suffrage Movement called the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. The Taiping movement had been influenced by Christian missionaries who arrived during the first Opium War. The group differed from the Temperance movement only in that opium replaced alcohol as the “demon drug.” The Catch-22 created by the opposing pressures of the Taiping Rebellion and the British opium demands led to the Second Opium War. This war’s outcomes included unbalanced treaties with the British and the collapse of the Chinese ruling class due to the Taiping.

These two decades of continuous war, coupled with rampant availability of opium, led to a massive increase in opium abuse and addiction within China. After the war, China had a difficult time rebounding due to the demands made upon them by the quadrumvirate of victors (the British, French, Americans, and Russians). The Chinese people were in a state of flux. However, because the treaty allowed open exchange with China, Chinese folks could immigrate to the United States freely, and did so in massive numbers. This large influx of Chinese immigrants into white Western cities eventually led to two famous pieces of legislation.

The more famous of the two is the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This act banned new immigrants from China for ten years and declared that current Chinese immigrants were not eligible for naturalization. Most of the drive for this legislation came from white workers, who had seen the influx of immigrants who were willing and able to work for lower wages as a threat to their hegemony. This anger led to violence against the immigrants.

At the time of its passing, the Exclusion Act was not the only law on the books that sought to punish the Chinese for simply arriving in America. Prior to that, other efforts were made to legislatively punish the Chinese. One piece of legislation connected race, culture, and drug in many of the same ways as the Temperance Movement in the East. In San Francisco, the city with the largest influx of Chinese immigrants, an ordinance was passed that prohibited the smoking of opium in opium dens. As these establishments were mainly run by Chinese immigrants, this was effectively a way to punish Chinese people without directly singling out their race or ethnicity. This less famous piece of legislation paved the way for the Exclusion Act by setting an initial precedent for anti-Chinese legislation.

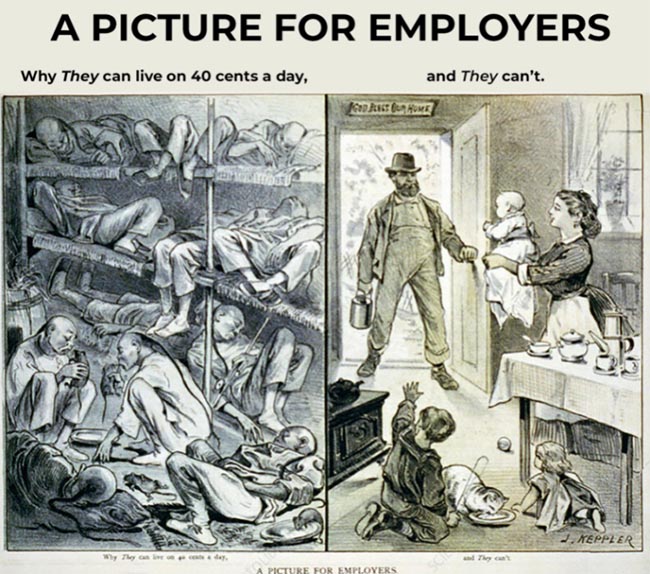

However, the legislation was difficult to pass without first gaining a majority of voters. While many did fear the immigrants’ impact on their economic stability, this was still not enough to pass the legislation alone. Prohibitionists and White Labor Leaders needed to build a coalition. To do so, they mimicked tricks and propaganda from the East’s Temperance Movement. In addition to being scapegoated for a Smallpox outbreak, Chinese immigrants were demonized for their use of opium. It was said that their usage of opium turned them into savages that would outperform white men, rape white women, and enslave white children to the drug. Posters were placed around cities and towns to portray these evils:

In summary, the British and its allies, including the United States, waged wars on China to ensure opium was forcibly entered into their markets. This allowed the drug to also enter the Chinese consciousness and culture. The increased availability of opium meant more Chinese people used the drug (and the effects of the war most likely caused more abuse and addiction, but we will get to that later).

As there were fewer opportunities within China to gain a livelihood, Chinese immigrants took the opportunity to move to America to work on railroads and in factories in the booming west. When they did, they brought opium with them, or maintained connections with opium sellers in China. Since they were willing to work for cheaper wages then white American workers, they were becoming a threat to white hegemonic control over the economy. Due to this threat, the use of the drug that had been forced upon them became weaponized against them to create a racist and xenophobic backlash to their very existence in America.

Without the demonization of Chinese immigrants as psychopathologized drug addicts, the San Francisco Opium Ordinance and the Chinese Exclusion Act would never have stood a chance. Interestingly, the Exclusion Act was a piece of Federal Legislation, meaning its racism and xenophobia had spread across the country. Continuing the cycle of sharing between the coasts, East Coast politicians and propagandists adapted some of the new Western strategies for use against freed slaves in the South.

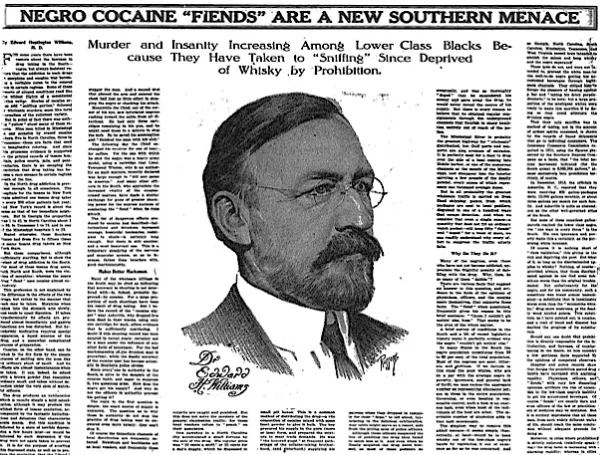

After the collapse of Reconstruction, and during the rise of Jim Crow, racist politicians and community activists were always working to identify ways to demonize black people—specifically, black workers who had now become a threat to white working class hegemony by being open to working for lower wages. Even though cocaine was widely used by the public, stories started to be told about the “Negro Cocaine Fiend” who would outperform white men, rape white women, and enslave white children to the drug:

African-Americans had started to become connected to this drug in ways that mirrored what had happened to Chinese immigrants. Except this time they ramped up the rhetoric. In these new stories, it was said that the drug had made them nearly impervious: “Bullets fired into vital parts that would drop a sane man in his tracks, fail to check the ‘fiend.’” The suspicion that someone was on the drug was enough to call for lethal action (which lives on to this day, unfortunately).

While the focus of the Temperance Movement had been alcohol during its inception, they started to focus on additional drugs of use and abuse. The temperate missionary William Jennings Bryant, who was Secretary of State in 1914, pushed fervently for the Harrison Narcotic Act. As narcotic use, including opium and cocaine (controversially identified as a narcotic by congress in 1914), was expanding around the world, fears over the drugs and their connections to foreign cultures and people of color increased. In response, the United States government participated in conferences regarding the “opium problem” with other “leading” nations in The Hague in 1911 and 1912. To solidify the outcomes of the agreements that arose out of these conferences, including agreements to prohibit narcotics such as opium and cocaine, the US passed the Harrison Act. This act effectively outlawed narcotic prescription, sale, marketing, and possession. But in a very controversial way.

The Harrison Act’s official title was “An Act to provide for the registration…to impose a special tax upon all persons who produce, import, manufacture, compound, deal in, dispense, sell, distribute, or give away opium or coca leaves, their salts, derivatives, or preparations, and for other purposes.” It also regulated the way any narcotic could be prescribed by a physician. Because of a clause that muddied the waters by stating a physician could only prescribe in the “course of his professional practice only,” law enforcement agencies assumed that any prescription or possession of the drug was criminalized unless an extreme underlying malady was occurring. If someone was up and about, walking the streets of a city, they obviously would never need the drug. Thus, the Harrison Act criminalized drugs such as opium, morphine, cocaine, and heroin (which up until that time had been one of the best-selling over-the-counter medications in the history of the country) for use, even with a prescription, unless you had a chronic and incurable condition.

Conclusion

While there had been anti-drug and alcohol activists within the United States since its inception, it was impossible to succeed in prohibition without tapping into non-activists. As alcoholic prohibition was taking hold on the East Coast in response to immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe (at the time, not considered “white”), equal efforts for prohibition were occurring on the West Coast, fueled by racist caricatures of Chinese immigrants.

While there can be no doubt that powerful drugs (including alcohol) can have deleterious effects, it was not until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that the thought of criminalizing drugs entered into mainstream American consciousness. By 1920, opium, opioids, cocaine, and alcohol were all newly prohibited by law, with marijuana to eventually follow in 1937. All these measures had been fueled by the fears of the effects of the drugs they prohibited. However, the clouds of nationalism, racism, and xenophobia distorted any serious conversation about drugs and their effects.

During the 1920s, prohibition had taken hold within the country, but new challenges arose. Black markets for alcohol and other drugs exploded across the country. While this occurred mainly in cities, rural areas were not immune (look up the history of NASCAR when you have time). Eventually, prohibition of alcohol became so disruptive and costly to maintain, especially during the Great Depression, that alcohol prohibition was reexamined.

In part three of this series, we will discuss the effects of prohibition on the country, how and why it was eventually overturned, and why other drugs (e.g. opium and cocaine) were not decriminalized. We will also be diving into the history of our nation’s most famous self-help group: Alcoholics Anonymous.

Editor’s Note: All blogs in this series are available to read here.

Enjoyable read. Thanks for the history lesson!

Report comment

Whoever created that WW1 ad didn’t have much understanding of the grunt mentality- it’s being able to get bombed at intervals that leads the grunts to stay forward without deserting. That guy in the soup bowl helmet need to get buzzed so he won’t be troubled by panics.

Report comment

Kevin that is a lot of history and research! Wow well done. When are you getting to the actual drug problem? The legal racket.

When will there be prohibition on all harmful drugs? Why are people not selling them to their friends? Anti-psychotic parties? The useless debilitating ones that pharma makes? Psychiatry looks to the illegal substances now, as they can get them with licence, plus the poisons that big pharma makes is going to get psych into trouble at some point.

They say no way, look at how knife lobotomies went on and no one charged the knife wielders. So we can use our lobotomy causing drugs since we are immune to prosecution and well things never change so guaranteed we are safe. 🙂

Report comment