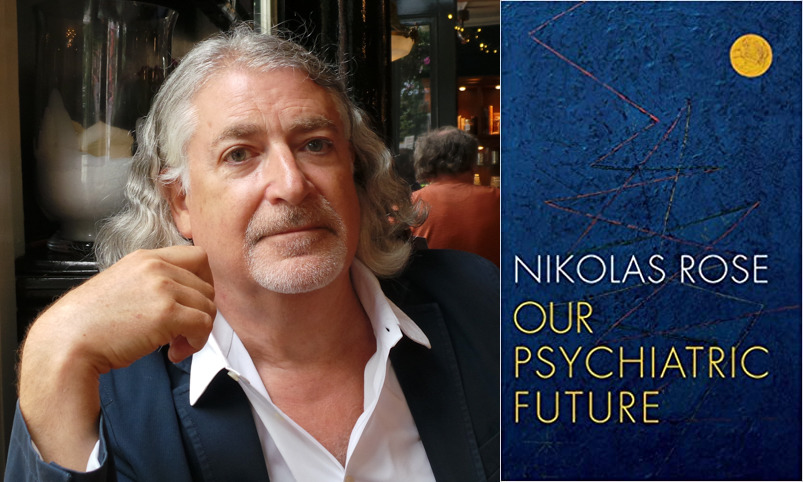

Nikolas Rose is a professor of Sociology in the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at King’s College London. His work explores how concepts in psychiatry and neuroscience transform how we think about ourselves and govern our societies.

Initially training as a biologist, Rose found his subjects unruly: “My pigeons would not peck their keys, and my rats would not run their mazes. They preferred to starve to death.” He moved on to study psychology and sociology and has become one of the most influential figures in the social sciences as well as a formidable critic of mainstream psychiatric practice.

A prolific writer, Rose has over fifteen books to his name, including, most recently, Neuro with Joelle Abi-Rached (2013) and Our Psychiatric Future (2018), addressing the most pressing controversies in the fields of neuroscience and psychiatry. He is also a former Managing Editor of Economy and Society and Joint Editor-in-Chief of the interdisciplinary journal, BioSocieties.

Throughout his work, Rose emphasizes that one must look beyond origins, or “why something happened,” and focus instead on the conditions under which ideas and practices emerge. The answers may not be comforting or straightforward, but they can help us to avoid band-aid solutions to complex problems.

Rose builds on the work of philosopher Michel Foucault to reveal how concepts in psychiatry and psychology go beyond explanation to construct and construe how we experience ourselves and our world. Consistent with Foucault’s oft-quoted adage, “My point is not that everything is bad, but that everything is dangerous,” Rose’s work avoids simplistic explanations of why and how the mental health fields go awry and instead examines how injustices can happen without unjust people. In this way, his work often transcends critique and imagines new possibilities and ways of thinking about “mental health,” “normality,” “brains and minds,” and, ultimately, the selves we might yet become.

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio of the interview here.

Ayurdhi Dhar: In your work, you point out that even though psychiatry and psychology (or the psy-disciplines) appear to be objective, they are actually built on societies’ “styles of thinking”—ways of thinking that no one questions. For example, in psychology, there is an underlying idea that things that happen outside of us, reach inside us. This assumption leads to research that attempts to locate trauma in brain scans and to theories about unconscious feelings or dysfunctional thoughts. How did you come to question these underlying assumptions? What led you into this area of inquiry?

Nikolas Rose: I went to Sussex University in the 1960s to read biology. We worked on fruit flies, which were the model animal for our Professor, the geneticist John Maynard Smith. This was a time when students across Europe were involved in protests questioning their universities and the associated political order. Despite my fascination with biology, and the craftwork of the laboratory, I did not think that the truth of those issues was to be found by studying fruit flies. I moved to study animal behavior, and then to human psychology

I found human psychology was a peculiar discipline. In conventional history, psychology has a long past but a short history: on the one hand it goes back to the Greeks, but on the other hand, around the end of the 19th century, psychology becomes a science when it embraced laboratory experimentation. I looked at this story, and it proved not to be the case.

One telling example was the concept of intelligence. When I started my own studies of these issues, there was a hotly contested debate about intelligence, so I started to study the history of this concept. In the late nineteenth century, the French psychologist Alfred Binet had been trying to understand human intelligence for many years. He got absolutely nowhere and felt intelligence was so difficult to pin down that one really could not have a usable concept of intelligence.

However, in the context of changes in the French schooling system, and the introduction of universal schooling, the ministry asked Binet to find a test to show which children would do well in ordinary schools and which children needed special schools. Binet invented a test aiming to identify those children who would need special education, and that became the first IQ test and the basis of what we think of as intelligence.

This is an example that the history of modern psychology does not begin in the laboratory, in philosophy, in speculative thinking, etc. It begins with very practical questions. It is not that psychology had great scientific knowledge of the mind that it was able to apply to practical questions. Rather, it seemed to be able to do a job in the practical world, and then it turned into a respectable scientific discipline.

My PhD thesis and first book The Psychological Complex showed how the psy-disciplines were not just ways of reflecting upon our world but crucial in the construction of key institutions, such as managing armies, reluctant factory workers, maladjusted children, etc. In all these practical places—the courtroom, armies, the schoolroom —the psy-disciplines were born. These practical ways of managing our lives now shape our ways of thinking in fundamental ways. We think, “Of course, some children are more intelligent than others. Of course, some children develop faster than others. Of course, some kids are more inclined to delinquent behavior than others.”

Dhar: Foucault’s work highlights that it was not simply that doctors had expert psychiatric knowledge, but instead, their stature created expertise. Similarly, it was not that asylums were healing, but because people were put in these places, they came to be seen as places of treatment.

Rose: Foucault points out that doctors gained control of the asylum not because they had great expert knowledge about madness, but because they were considered to be wise people in light of a series of scandals around the commercialization of asylums and their terrible conditions. Europe and North America began to regulate how people got into asylums and decided it was obviously through the doctors because they considered them wise trustworthy people.

Foucault also helped us question the whole idea of “origins.” Birth of the Clinic showed that the doctor’s “clinical gaze” emerges as a consequence of a whole series of contingent things that happened at that time, such as changes in French laws of assistance. When people were sick and needed free healthcare, they had to go into hospitals.

Changes in ideas of citizenship: if you went into hospital your name is written down, you now have a case history, and people observe you as your condition develops day after day, week after week. This made it appear that there was a general pattern of progression of a disorder.

When all these contingent developments came together, they created the conditions for this clinical gaze. The general lesson is that you should never look for origins, never ask ‘why’, but instead ask, “how did this occur?”

Dhar: Much of your work has to do with the writings of Michel Foucault. What was it about his work that resonated with you?

Rose: Foucault provided me with some conceptual tools to make sense of the questions I was interested in. He says somewhere, “History is not so much for knowing, as for cutting”—cutting into questions and making them intelligible.

The emergence of the psy-disciplines is about the emergence of a certain “style of thought.” Thought is not peripheral to history: systems of thought make things possible to think, to understand, and to do.

Foucault’s Madness and Civilization had a profound effect on me because it was not really a history of psychiatry; it was a prehistory showing under what conditions something like psychiatry could exist —with its asylums, its doctors, its diagnostic classifications, etc.

As a student, I entered the world of psychiatry, going to mental hospitals, seeing patients that were being demonstrated by the doctors. I wondered how some of the patients’ thoughts that seemed quite normal to me were seen as psychiatric symptoms.

I saw some treatments that were used before the huge rise of psychiatric drugs, for example, aversion therapy, which was used for homosexual men. Electrodes were attached to their genitals, and when they felt aroused after being shown stimulating images, they were whacked with electric shocks.

This was absolutely horrific, and yet the people doing it seemed to be decent, humane scientists, not concentration camp guards. How could they think and do these things and believe that it was not only legitimate but scientifically justified? That it was objective and a form of therapy grounded in scientific research?

These things made me question how these ‘styles of thought’ have come into existence and how they produce certain types of professionals—the little experts of ‘psy’ who we now see in our schools, armies, hospitals, prisons—little experts of psy everywhere.

Dhar: That’s the importance of knowing history; these methods that seem so horrific right now, were once shown to be effective in studies.

Rose: Yes. If one looks at the debates in psychiatry around World War II, there was excitement about physical psychiatry—electroconvulsive therapy, lobotomies. It seemed we had techniques that worked and that we could get into the brain and alter it. These views and hopes were shared widely among psychiatrists. The question today is: in 50 years, are we going to think the same about psycho-pharmaceuticals?

In fact, I think we are at a turning point with the drugs. More and more people are beginning to recognize that they don’t work very well and that the so-called side effects are just as damaging as those of the older tardive dyskinesia causing drugs. Brain research shows that some of the medium to long-term consequences of disorders are the consequences of taking the drugs chronically.

Schizophrenia was once thought of as a chronic degenerative condition until it became clear that degeneration was a consequence of institutionalization. Are we going to look back in 50 years and think that our obsession with these small molecules is just as bizarre as those earlier treatments? I think the jury is out on that.

We are in a paradoxical situation. More people worldwide are taking psychopharmaceuticals, in particular the SSRIs and SNRIs, yet at the same time, research is beginning to question whether they are effective and starting to reveal their adverse effects.

These drugs are given by GPs (general physicians) who think that the drugs cannot do any harm. They say, “I used to give my patients tranquilizers, Valium, etc. They were addictive. At least these drugs can’t do any harm.” We are beginning to see that this story is problematic.

Dhar: Research now suggests that antidepressants have long-lasting and severe withdrawal effects and that antipsychotics may lead to psychotic symptoms. What puzzles me is that, despite all this research, the neuro-biological position and the biomedical paradigm have not lost any vigor or power. What gives it this power?

Rose: If we put aside, for the moment, the general question of whether the drugs ‘work’, some of these drugs can, for some people, provide some short-term relief, which might enable a person to step back from an overwhelming crisis, in order to address the real issues. But the problem with all these drugs is their chronic administration and increasingly higher dosage with the assumption that if a drug stops working, add another one. So, polypharmacy is the norm.

Instead of these drugs being treated as something that, for unknown reasons, produce some short-term relief, we believe first that we know how they act on the pathway of the disorder—which has never, ever been demonstrated. Second, we believe that their effects are beneficial, so if people start getting adverse effects when they come off the drug, it is attributed to the disorder and not the consequences of withdrawal.

The tragedy is that since the 1960s, this particular paradigm has hegemonized psychiatric reason—all psychiatric disorders are about the receptors, and treatments must act on anomalies in the receptors. And these drugs work on the receptors; if it’s not dopamine or serotonin, then perhaps it’s glutamate or something else, but it’s bound to be in the receptors!

I worked with the European Commission-funded Human Brain Project, and everything that we know about the human and primate brain tells us that these are hugely distributed redundant systems —You don’t just touch one bit, and that’s it. The brain is dynamic. If you change one thing and everything changes!

We are in a very primitive state with brain interventions. As far as the drugs are concerned, in the UK at least, there is a beginning of questioning the current paradigm. There’s interest in alternative drugs such as the old psychedelics, such as LSD, which, in the history of psychopharmaceuticals, were believed to produce effects that were similar to some psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia. Today some argue that low dosages of these drugs have considerable therapeutic efficacy. But this approach is treated in a rather hostile fashion by our government and regulators.

Dhar: You write about psychiatry’s ever-expanding diagnostic boundaries and how it has turned general discontents of life into diseases. Other authors have blamed big pharma, neoliberal capitalism, etc. but you say it is more than that. Can you elaborate?

Rose: Let me take a very contemporary example. We are in the midst of a pandemic, and newspapers are filled with stories about its mental health consequences and claims like, “There is a mental health tsunami coming, we need more psychiatrists and better access to their services!”

Of course, people are anxious as their lives are turned upside down, especially those who are already living in conditions of adversity and cannot stay off work, self-isolate, and so forth. It is understandable that people are worried and scared, but now this language of the emotions is not enough. Somehow all of this is recoded as problems of mental health.

It is now incredibly difficult to say that perhaps it is better to use the language of the emotions, that people are just fed up and miserable seeing their loved ones die. These are normal experiences and not symptoms of mental problems requiring individualized interventions by an army of psychologists.

We should step back to think about why the people most deeply affected are people from black and minority ethnic groups, living in the worst possible forms of housing, overcrowded places, who are financially vulnerable, etc. We could think of intervening on those things, but no, the language of mental health has become a way of coding our everyday discontents.

It was in the period after the Second World War that we began to see the argument that mental disorders were not confined to a small number of people in asylums but were very widespread in the population—that probably all people are affected by problematic mental health at some point in our lives and that these problems need recognition and treatment by psychiatrists.

The famous British social psychiatrist Aubrey Lewis said that there is no other profession that, when given a problem and asked if they can help, is so likely to say ‘Yes.’ You give psychiatrists problems of naughty children, reluctant workers, homeless people, and they seldom say, “that’s not our problem,” but, “yes, we can say something about that.”

They have embraced all these problems; the boundaries have spread and spread and we don’t know where to limit who is “a suitable case for treatment.” We are all pre-symptomatic and at risk of something or the other. In physical medicine, the mantra is the earlier that you detect and treat the better, so why not in psychiatry? Earlier intervention for kids, for first-episode psychosis—this is psychiatry thinking of itself as a public health vocation.

Then psychologists look outside Euro-America and think those populations are deprived access to these interventions, and we have the Movement for Global Mental Health. Psychiatrists believe that they know, they have a style of thought that has the potential to know, even if it does not fully know now, that this is the way of thinking and knowing.

They think they have treatments that work and that, even if they do not work very well, they’re on the right path to working. Because they think they know how to know, and they know how to treat you, even if neither of those is perfect at the moment, they feel that people should not be deprived of them because of the accident of their place of birth.

For me, unlike many critiques of psychiatry, I think it is important to understand why psychiatrists think the way they do and to understand the many internal arguments. We must collaborate with psychiatrists from the point of view of critical friendship to understand how they think, to question them, and the weaknesses in their evidence and arrive at alternatives. I find this more effective in helping transform psychiatry and what it does.

Dhar: Service-user groups are now thankfully beginning to be included in decisions about mental health. But we know patient advocacy groups are often taken over by pharmaceutical company interests. Do you think service-user or survivor groups, now that they are included in policy-making, will get co-opted like patient advocacy groups?

Rose: Foucault said that the rise of psychiatry cast off into the wilderness all those stammering half-formed phrases with which the dialogue between reason and unreason used to happen and the history of psychiatry is the history of that silence.

One of the changes is that the silence has been broken. Any report on the future of psychiatry, such as the Lancet commissions reports, cannot be written without reference to the lived experience of people with mental distress. Ideally involving one or two of them as authors, although exactly what power they have in shaping that narrative is uncertain.

The involvement of the patient’s voice is the most significant thing to happen in psychiatry since the invention of psychopharmaceuticals, and it has the potential to transform psychiatry, to make psychiatry answer to the demand that if it claims to be for the benefit of the people it serves, at the least it should listen to their voices —to our voices —as to what we think is good for us.

I think this is a challenge to the power of psychiatrists—not just to listen to voices as symptoms. But there is a multitude of problems—survivors being used to give legitimacy to status quo practices, the survivor being seen as just telling their story, which then has to be reframed in psychiatric terms, articulate survivors are thought to be non-representative of the others, etc.

Survivors often are not given the power to shape the research strategy, research questions, research interpretation. People in user and survivor movement in the UK are very aware of these challenges. There is a danger of co-option, but co-option is not the inevitable destiny. We are in the middle of something, and groups like Mad in America who foster survivors’ voices and survivor’s stories play a crucial role.

We must recognize that people who have experienced mental distress and the mental health care system offers not only lived experience but a different kind of knowledge, no less valid. This knowledge is worked out in collaboration with others; it is open to challenges, able to give evidence, open to question, but a knowledge of what it is like to live with these conditions and to live with the therapies for these conditions.

Like psychiatry itself, user and survivor movements are riven with conflict. For example, there are questions about whether they are dominated by the global North? Are there autonomous knowledges in the global South? Is there some virtue in traditional methods of healing? How should one relate to developments such as the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the idea of ‘psychosocial disabilities’? The conflicts are not a problem; contest and argument are how things develop.

Dhar: You have written about “risk-thinking.” We live in a time where measuring and identifying risks is embedded in our culture. For example, we use genetic tests to find out susceptibility and the many assessments in schools and offices. How does “risk thinking” and the psy-disciplines work together to influence how we feel about ourselves?

Rose: Canadian philosopher Ian Hacking talks about risk thinking as bringing the future into the present. This makes us feel obliged to think about these futures in the present. Then we feel obliged to do things in the present to influence this future. Imagined futures are always present to us, and so it appears irresponsible not to do something about them.

If you are told that eating hamburgers twice a day will increase your chances of having a heart attack, then it seems irresponsible to keep doing it, even if we live in an obesogenic (obesity causing) environment where hamburgers are cheap and so we can afford to feed our kids. This inducing of a sense of personal responsibility for our bodily futures has become very widespread. our responsibility is not about living a virtuous life or doing good in the world, but about managing our corporeal existence, our weight, diet, etc. in the present in the name of the future.

This is coupled with a series of technologies that claim to bring the future into the present and make it calculable to us—the scans, the genetic tests, etc. While in some cases, such as cancer, there is evidence that one can do something in the present to change the future, in others this is not so clear.

As well as these highly ethical issues, there are technical questions. Take, for example, mammograms. How many people do you need to screen to save one life? What are the consequences of the high numbers of false positives and negatives; what about the fact that many early signs that might be used to warrant early intervention would never develop into tumors. Similarly, for prostate cancer in men, there is an antigen test to pre-identify people at risk. Is the knowledge of the future and the intervention going to cause more harm than good? In the case of the prostate test, many men had surgical interventions that had major consequences for them, but most men who have prostate cancer will die with prostate cancer, not from prostate cancer.

For psychiatry, the questions become even more difficult because the markers cannot be found, and effective interventions don’t exist. You are left with the statement that someone is a high risk without specificity about what that risk indicator is, and without any interventions that are going to mitigate that risk. But what you do get is the stigma and other consequences to the individual themselves and from others thinking that someone is at risk of developing a mental disorder.

With the Psychosis Risk Syndrome argument, the vast majority of people who have one of what appears to be a psychotic episode, never go on to develop future psychosis. Even if we knew exactly what we were talking about, evidence suggests that it is a very bad move to start making those early diagnoses, because it carries all the downsides of being identified as a person at risk—thinking of yourself as a person at risk, your parents and your teachers watching for symptoms—leading to the looping effect.

‘Risk thinking’ in psychiatry leads to the idea that a diagnosed person is likely to be risky towards others, and hence is subject to all sorts of risk assessment procedures simply because they have a psychiatric condition, this can lead to serious injustices. People can be subject to long periods of involuntary detention or supervision based on rudimentary and questionable risk assessments.

There is a kind of industry of risk assessment with financial benefits for psychiatrists who are brought in as consultants. When I gave a paper on this to a psychiatric organization that shall remain nameless, I said we should stop being blackmailed by the government to make these risk assessments because we are not good at it. All the psychiatrists there knew that they were very bad at making risk assessments, but giving up the business of risk assessment meant giving up on the second car, the fees for the private schooling for their child, etc.

Of course, it is not just or mainly psychiatrists—there is a huge biotech industry seeking to promote and profit from the invention of risk assessment devices despite the many problems of indicators of risk.

Dhar: You write about psychiatry’s singular focus on the brain and how it affects how we understand ourselves. Could you talk about this concept of ‘somatic individuality’ and how the psy-disciplines alter our sense of ourselves?

Rose: Somatic individuality is the sense that our identity depends crucially on our body—its shape, its size, its fitness, its capacity, etc. So, managing our bodily existence now becomes the most virtuous thing that we can do. The slogan ‘our bodies, ourselves’ has taken on a new meaning—our selves have become very tied up with our bodies.

Brain research has made fantastic progress over the last 30 years. We know more about human brains than ever before, but the more we know, the more we realize we don’t know and understand. We understand very small-scale molecular events within the brain, but we do not how those play out across the huge complexities of multiple synapses and cortical pathways.

We do not know clearly how brains are located in the body because they are often studied in an isolated fashion in laboratories or animals like mice. In so many studies, brains are not embodied, and the bodies are not placed in an environment, and the environment is not placed in time and space. Until we can begin to think about that, we will not fully get how brains work.

There was a reductionist hope that we would start by understanding the smallest building blocks of the brain, the molecules, and synapses, and gradually work our way up to the brains of simple creatures and then humans. Going up the scale has proven to be impossible to do, let alone placing all that stuff in space and time.

We should not cast out neurobiology, but we should start with the human brain as it is, as it develops in an organism from conception onwards, always in interaction with its environment. Everything about the brain is shaped by and involved in making actions in that environment possible.

This is actually a more scientifically accurate way of researching the brain. We have come to the end of these reductionist approaches because they proved unable to answer the questions which they set themselves, and they unable to understand how you and I can be doing the weird things that we’re doing now—talking, thinking, communicating, etc.

Thus, I support the development of a new relationship between the neuro-biological and the social sciences in which we work together to understand how our social and political environment shapes who we are. To put it the other way, if people are experiencing mental distress, how can we understand that in terms of their relationship to their bodies, brains, and human existence in those environments? How can we intervene in their relationship with those environments and not just molecular structures? I think about these things in a biopsychosocial way,

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

Thank you Ayurdhi

Great interview.

“As a student, I entered the world of psychiatry, going to mental hospitals, seeing patients that were being demonstrated by the doctors. I wondered how some thoughts that seemed quite normal to me were seen as psychiatric symptoms in patients. I saw prevalent treatments like aversion therapy, which was used for homosexual men. Electrodes were attached to their genitals, and when they felt aroused after being shown stimulating images, they were whacked with electric shocks.

This was absolutely horrific, and yet the people doing it seemed to be decent, humane scientists, not concentration camp guards. How could they think and do these things and believe that it was not only legitimate but scientifically justified? That it was objective and a form of therapy? That it was grounded in scientific research?”

“…and yet the people doing it seemed to be decent, humane scientists,”

Report comment

Just as in warfare, justification of such things depends on dehumanization of “the enemy.” The only way “decent” people can do horrific things is when they have been convinced that the person they are doing it to is not fully a person.

Report comment

And it continues in an supposedly aware society.

Report comment

“but suddenly, around the end of the 19th century, the psy-disciplines become sciences.”

No eugenics is not science it’s a major crime against humanity nor today is voting conditions into existence, this is financial fraud which also plugs into eugenics. Now we have them spreading the fraud – SSRI’s for pain management and for headache/migraine.

“Electrodes were attached to their genitals, and when they felt aroused after being shown stimulating images, they were whacked with electric shocks.

This was absolutely horrific, and yet the people doing it seemed to be decent, humane scientists, not concentration camp guards. How could they think and do these things and believe that it was not only legitimate but scientifically justified? That it was objective and a form of therapy? That it was grounded in scientific research?

These things made me question how these ‘styles of thought’ have come into existence and how they produce certain types of professionals”

No they are not professionals and it is not ‘styles of thought’. They are abusive homophobic criminals.

“Schizophrenia was once thought of as a chronic degenerative condition until it became clear that degeneration was a consequence of institutionalization. Are we going to look back in 50 years and think that our obsession with these small molecules is just as bizarre as those earlier treatments? I think the jury is out on that.”

No the jury is not out on that one, it wasn’t bizarre it was criminal and it’s criminal now.

“They say, “I used to give my patients tranquilizers, Valium, etc. They were addictive. At least these drugs can’t do any harm.” They are beginning to see that this story is problematic.”

No they know but they keep on doing it just as someone like Joanna Moncrieff knows but continues to be a psychiatrist and therefore subjects people to toxic drugs. I’m afraid they are going to have to be stopped from harming people.

“I’ve been practicing psychiatry for 20 years, and in my experience antidepressants don’t do any good at all. I wouldn’t take them under any circumstances – not even if I were suicidal.”

20 years – I mean isn’t it obvious?

“Some of these drugs can, for some people, provide some short-term relief, which might enable one to step back from the overwhelming crisis, in order to address the real issues”

No a psych drug can’t help a person to step back, it disables them. For sure if a close caring friend intervene this can achieve a lot depending on what the friend knows and their experience.

“If people start getting adverse effects when they come off the drug, it is attributed to the disorder and not the consequences of withdrawal.”

Guess what your colleagues are right now ripping people – who have been long term 6 months plus on AP’s – off AP’s in two weeks. They are now doing this with over the phone interviews.

“You give psychiatrists problems of naughty children, reluctant workers, homeless people, and they will say, “we can say something about this.”

They don’t say “we can say something about this.”they abuse with vile drugs chasing homeless around with their depot injections in MacDonald’s. Search in my comments history and you will hear a psychiatrist saying this.

“They think they have treatments that work and that, even if they do not work very well, they’re on the right path to work. Because they think they know how to know, and they know how to treat you, even if neither of those is perfect at the moment, they feel that people should not be deprived of them.”

Oh yes indeed, make them feel deprived of abusive treatments.

“Survivors often cannot shape the research strategy, research questions, research interpretation.”

That speaks alot about you.

“We must recognize that people who have experienced mental distress and the mental health care system offers not only lived experience but a different kind of valid knowledge. This knowledge is worked out in collaboration with others; it is open to challenges, able to give evidence, open to question.”

What we want is for psy to die and be outlawed for it’s major crimes against humanity, those guilty be locked up and stopped from ever subjecting people to their horrific drugs and payment be made to those harmed and family of those killed.

“Like psychiatry itself, user and survivor movements are ridden with conflict.”

NO we are NOT like psychiatry.

“At a psychiatric organization that shall remain nameless, I said we should stop being blackmailed by the government to make these risk assessments because we are not good at it. All the psychiatrists there knew that, but stopping the business of risk assessment meant giving up on the second car, the private schooling for their child, etc.”

Psychiatrists are good at destroying and seriously harming peoples lives. Who is going to assess that?

Report comment

Thank you Street.

Report comment

Welcome Sam

” Rose’s work avoids simplistic explanations of why and how the mental health fields go awry and instead examines how injustices can happen without unjust people. ”

My view is that it is blindingly obvious and if it actually happened to this person it would be shockingly visceral and simplistic but not in any word way. When a bomb is going off in your head be it slow or fast, words are not there. The action is – how the hell do I get out of this, someone fucking well help me. Well that help is to be forcibly held down and injected with more toxic crap. This is the crime and it needs to be brought to justice.

These people (king’s College London psych lot) have no real concept of what’s been done and the scale of the crime, the horror that’s gone on inside peoples heads by having toxic drugs forced into them, the normalised depravity and closed culture abuse of psych units. No that’s wong – they do indeed know.

Report comment

“they do indeed know.”

True words spoken, street.

Report comment

@streetphotobeing: Although I don’t believe in a monolithic ‘psychiatry’, that is, there are many levels and boundaries, I appreciate all these points. I call it ‘conventional’ psychiatry, and ‘it’ dominates the field. But I know THAT is also not fully satisfying. You shimmied through many of the interviewee’s cracks; many of which I didn’t catch at first glance.

Report comment

“Rose builds on the work of philosopher Michel Foucault to reveal how concepts in psychiatry and psychology go beyond explanation to construct and construe how we experience ourselves and our world. Consistent with Foucault’s oft-quoted adage, “My point is not that everything is bad, but that everything is dangerous,” Rose’s work avoids simplistic explanations of why and how the mental health fields go awry and instead examines how injustices can happen without unjust people. In this way, his work often transcends critique and imagines new possibilities and ways of thinking about “mental health,” “normality,” “brains and minds,” and, ultimately, the selves we might yet become.”

The real evidence should point us to what injustice looks like. And are injustices committed by unjust men? Of course they are not “injustices” in a “legal” sense if laws allow the perversions and abuses of men to be legal. And on a philosophical level, of course you can make endless allowances for injustice, Or “just men” by the possibility that no such meaning is definable in that “philosophical” way.

So one always has to ask the one who was overpowered. “did you experience justice?” It is not up to Mr. Rose to decide what a “just man” looks like. We can sit and contemplate “just men” forever while sitting under a tree eating our granola. What a privilege.

The “justness” is in real evidence.

By, “Just men”, I’m hoping Mr. Rose was referring to the meaning of “merely men”. Men involved in caring about “justice” don’t do “just a little bit of damage” or even ponder the meaning.

Report comment

“Human suffering arises from our embodied interaction with a world, that though it cannot be known cannot be wished away.”

This is a very thoughtful interview with a very thoughtful, sensitive and erudite man. Thanks. But despite this well reasoned stance which often seems beyond argument, despite the considerable evidence which is easily accessible, despite the fact that psychiatry usually employs educated, cultured and seemingly decent individuals to do its business it carries on oblivious to the evidence. Its failures, mistakes, sometimes downright horrors continue. Why?

It’s not because their monstrous people – It does us no favours to dehumanised psychiatrists as we have been dehumanised. But still psychiatry exists with, despite many changes, the same basic mindset that Denys the harm that adversity, oppression, abuse and neglect cause people. Not only that but it has expanded its enterprise, sees more people treated than ever before (by a long shot) and despite the recognised proven failure of its treatments seeks ever more confidently to expand further into society. Why? How can it get away with this blind indifference to people suffering to reason even as it claims to be reasons best protector?

Report comment

Because we don’t name their dehumanizing. Because most people think they are good people. And so are

those that commit crimes, “good people”

But good people who commit crimes go to jail.

Most people “wish” that people did not commit wrong, but rather behaved like the “good people” that they are.

Report comment

Sam

You might want to check my answer to your comment in the “Around the Web” section of MIA.

https://www.madinamerica.com/2020/08/abolition-must-include-psychiatry/#comment-177050

Richard

Report comment

sam plover: Thank you for your reply on a separate comment of mine below. For some reason, there is no reply button under your or I_e_cox’s comments to me, and so I can’t reply directly for now. I don’t know if that’s intentional by mediators or a bug in the forum. I guess I’ll wait to see if it comes back and reply more fully then.

Report comment

POSTING AS MODERATOR: When a certain number of “levels” are reached under a particular thread, the “reply” button disappears on new comments, and you have to go back to the last one that has a “reply” button and use it, and your post will end up at the end of the thread. It’s a feature of WordPress and not something we have control over.

Hope that helps!

Steve

Report comment

Steve: Thank you very much for clarifying that for me. I just posted in line with what you said, right before I read your post. The virtual/coding/computer world is so complicated and particular. You’re a bold and persevering man to deal with both the software and communication/informational. Thank you for moderating. It is critical.

Report comment

You are welcome!

Report comment

@Whatuser: I agree. I’ve been chewing over this a lot: ‘Society‘ doesn’t know, doesn’t want to know, and will do whatever it takes to prevent from knowing, even if that means fighting, abandoning, or incarcerating.” I agree that people should be careful not to blatantly dehumanize psychiatrists and the culture constellated around them. But it’s so difficult not to outright reject it, or to tame a response when properly assessing or changing the culture, without being loud, angry, and demanding various forms of justice or dismantling.

Report comment

I see that you are uncomfortable with the urge to “dehumanize” psychiatrists.

Do you think that is what we are doing here? Whatuser echos this concern: “It’s not because they’re monstrous people…” I would only note that in this statement, they remain “people” and so technically have not been dehumanized by the statement. Monstrous PEOPLE do exist! Do you not agree?

I agree that to accuse an entire profession of being criminal looks like the application of a very blunt instrument. Yet if there is any group we would be justified in generalizing about, it would be this one. Are you aware of this group’s background and legacy? Are you aware of what their leaders have said and planned and done?

There were, perhaps, “good Nazis” too. But if you were essentially a good person, why would you associate yourself with a group like Nazis? Perhaps some medical students are unaware of the atrocious history of psychiatry, or somehow expect that they will not turn out like that. But wouldn’t it be wiser, if you knew the truth, to just walk away?

Perhaps some commenters here pick their words a bit carelessly. But most of us really want the entirety of what is known today as the subject (and profession) of psychiatry to go the way of Eugenics, or Race Science, or policies like forced euthanasia. We want psychiatry to die as an active, practiced body of thought. At least we want the human rights abuses to end. But in the case of psychiatry those are closely related goals, as the purpose of the subject seems to be to violate the rights of people without them realizing it until it is too late.

Perhaps the concept of the criminal mind is foreign to you, or you feel it is incorrect or outmoded. Perhaps it makes no sense to you to label an entire body of thought as criminal. Well, we should probably work harder here to make these things more clear! It is worth discussing.

Often contained inside a troubled “science” are the seeds of its own destruction. But I would advise all visitors here to learn what you can about the condition called “antisocial personality disorder” before they remove it from the list of “mental illnesses.” It seems only a matter of time before crime becomes embraced by”modern” culture as legal! We see it happening all around us now. If we do not speak out strongly for what is right, we could lose any remaining freedom we have to speak of this in public. That is my concern, and that is why I try not to mince words about this subject.

Report comment

I_e_cox: Let me see if I can thoughtfully respond to your comment without you criticizing me to death. Hopefully, it is relevant to this article because I tend to not like straying too far. I have a feeling like I have here.

First of all, I’ve had the habit of saying about most psychiatrists I’ve seen, about 12 and especially the hospital ones, that “they are dead to me”, “they are not the brightest apples in the basket”, that “I regret having to be at their mercy”, and that “they should be ripped a new a$%hole”. That it’d be a joke if it wasn’t so serious. That I’d simply be disappointed and embarrassed if it weren’t so dangerous. I don’t consider them my colleagues and definitely not my friends. Does that give you sense of my opinion on most psychiatrists? Does that resonate with your agenda and allow you to see me as an ally and not an enemy? By the way, I believe the enemy is intrinsic to human nature and the universe. If we, what?–kill?, all our enemies, we will still have to look into our own void and the great dying and betrayal of nature. My goal is to replace a greater evil with a lesser evil. Are you suggesting that we DO dehumanize people, or more particularly, monstrous people? Even murderers who have spent 30 years in prison can act sanely and with repentance, if not morally and purely good. Even they are more likely to become that way with a certain amount of dignity and as humane a treatment as possible. Are you suggesting we lock ALL of psychiatry in prison for life or inflict the death sentence? I know you mean ending their career and holding them accountable, but…..Perhaps we agree that some of the most mentally ill people run the mental health system, and some of the most criminal people run the criminal justice system.

I have spent over 20 years studying many of these issues, as a person labeled and as a researcher, and I learn things every day. I do think these things are worth discussing, and while I won’t spend a weekend workshop with you on this, I will try to be open to dialogue. When you say you are comfortable labeling an entire body of thought as criminal, I find that very familiar, as I’ve spent a great deal of time in the mental ‘health’ system and some in the criminal ‘justice’ system, and I saw first-hand how that tendency goes both directions in a tragic way. My drug court judge was one of the most angry, controlling, sadistic people I’ve ever come across. (I can’t say I really MET him). He doesn’t feel what he’s doing. He always finds the enemy outside, so very easily found, and only knows how to put his weapon in other people, doing so by the thousands. Do I think he, and psychiatrists, need to get a dose or 500 of their own medicine? Yes, I do.

I also don’t wish to mince words, and I try my best to be clear and concise in such a limited format as this. Now here’s where you and I seem to radically disagree. Two of my favorite authors were psychiatrists. Abram Hoffer, and Carl Jung who was a psychiatrist before psychiatry became more physical. Neither one is well integrated into the monolithic profession you are tying all together into a bow. They both had major blind spots, frank mistakes, and probably hurt some people along the way. I don’t intend to blur those distinctions. There is a place for physiological and psychospiritual shamanism and healers of the tribe. These doctors tried not to abuse civil rights, tried to work with people, whether patient or otherwise, and were both pioneers. When they died, thousands and thousands of people gave their condolences. Millions have bought their books. Hoffer did use ECT early in his career–always using high dose nutrients and not recommending it without them–but abandoned it later, and in my opinion, had too limited notion of the psychology and the medicalization of schizophrenia. Jung believed schizophrenia was a valuable term, but tended to be unsuccessful, according to him, of treating what he labeled. Each doctor found what the other lacked in some ways.

So do I think psychiatry needs to be ripped a new a$%hole and be forced to look behind its own mask? Yes, I do. Do I think there’s no room for soul-healing, psychic and neurological leadership, that enhances life and diminishes pain and lostness? Of course not. Destroying seems to be easier than reconstruction. And criticism should be as constructive as possible. I love Jung and Hoffer, and I don’t usually equate them with Nazis. Even if 20th century psychiatrists are ALL not your thing, perhaps tribal shamanism is? The guide, the healer, and the myth-maker that tries his damnedest to connect the dots, inspire his tribe with song, dance, and plant medicine, and listen to what the dreams are saying? I’m trying my best d$mnit. Please don’t make me feel like you want duct tape on MY mouth and cut the ground from beneath MY feet; and that I am not wise enough to be welcomed in a forum such as Mad in America. Perhaps these are not your intents. I am not a Nazi, nor do I have sympathy for them. I have no intention of becoming the chronic angry and sadistic control-freak like my drug court judge, or the more subtle tight-lipped psychiatrists that think they’ve seen my true nature within 5-15 minutes and hang me out to dry. I’ve had to fight very hard to not become my own worst enemy.

I welcome your response, but like I said, I won’t get into the thick of it beyond a certain point. Have I made it clear to you that I want the abuses of human rights to stop too? And that I work every f*$&ing day to find freedom and health for myself and for others? If I have not, then I, you, or both of us have failed. I will wake up tomorrow and try again. Grateful for the fact that I am not suicidal, that I don’t have to deal with most conventional psychiatry anymore, that I have food and a roof over my head. And that I can use my voice in a way that I choose, rather than pray into the darkness for The God to kill me. Or with a voice that IS no voice, a voice that knows very well what dying is like. Take care.

Report comment

It seems to me a bit that we are talking past each other. That’s all right. I write my comments for all to read, not just the one I am replying to. Particularly because I barely know most of you, but also because this is a public dialog, not a private one.

I have never formally studied psychology or psychiatry. I have never read Freud, Jung, Adler, Hoffer or any of the rest of them, except for a tiny bit of Berne. My interests led me to material of a more spiritual nature. I write from that viewpoint.

Are you familiar with the material I refer to? Rees’ 1940 speech about being a “fifth column?” Chisholm’s rant against morality? The avid participants in MK-Ultra? It is not that these men typified the profession. It is that the profession tolerated them.

And you don’t mention the problem of ASPD. Neither do most psychiatrists. I think they’d like to remove it from the DSM. Maybe some day they will.

My purpose here is to speak for the diminishment or eradication of current psychiatric belief and practice. That won’t make Jung go away, and that doesn’t bother me. His contributions extend far beyond the field of psychiatry. But this is my basic position and I try to argue for it and to caution against a more lenient viewpoint. There are a lot of lives at stake, and I try to keep that in mind.

Report comment

evanhaar,

“Please don’t make me feel like you want duct tape on MY mouth and cut the ground from beneath MY feet; and that I am not wise enough to be welcomed in a forum such as Mad in America.”

Hope you don’t mind if I say something to this. btw, nice post. It is most important that you are welcome here, which you are by the sheer fact that you are posting and it is accepted by MIA and read. I mean you are here to post and have people read your opinion, so is L. I enjoy both your posts. They are both equally valuable to me. I don’t have to agree with every word.

Report comment

I_e_cox and sam plover: Not sure why I couldn’t directly respond to your comments, but I will try this and leave it at that. To both of you: If I could edit my previous comment, I would delete my statement about duct tape etc. I think this website, overall, is so bada&%, and is such a great resource. It allows people from all over the world to transcend their locality if necessary and find avenues of expression that are often delegitimized, overlooked, and forgotten by ‘standard’ care and ‘standard’ society. Sam’s comment that one doesn’t need to agree with my every word is so true for everything. I edit my website a lot, for awhile there constantly, and am so glad because life needs a constant EDIT. I read the Commentary Guidelines for this website, and I was so impressed by the mindfulness and thoroughness of it. Anyways….

sam plover: Thank you for your response. I’m glad you found value in my comments. See you around on the forum. I’ve noticed you post a lot, and I appreciate that.

I_e_cox: It is easy to talk past each other. I will try not to. I don’t know about ASPD, and that’s one reason I didn’t respond. I will try to google it sometime. There are so many nooks and crannies in diagnostic/labeling. I tend to speak more for schizophrenia, depression, and anxiety because they’re what I’m most familiar with, although I try to keep up to date on everything. I’m a little confused on your position on ASPD. Do you want it to be removed from the DSM? Do you think it is a legitimate label or will you be glad to have it removed?

I relate to your caution of leniency of many of these things. I have not familiarized with the 3 historical areas you mentioned. I know a tad about MK-ULTRA, and its experiments with LSD for mind control by the CIA. But really beyond that sentence, I know nothing. I’m very interested in psychedelic history and research, but admittedly, I have focused more on other areas that aren’t as explicitly evil as MK-ULTRA. I am prescribed microdoses of affordable generic ketamine, and it has been a blessing. It also resonates with my original interests with psychedelics, which conventional psychiatry always and only pathologized, etc. I don’t want to go into my particular use of this, so let’s set that aside, although I’d say my generic version transcends the expensive, time-consuming, and clinical over-control of the patented nasal spray and the IV routes, which though interesting, are impractical, nowhere nearby, and rub close against many of the typical ‘Big Pharma’ problems. I hope to have another full psychedelic and spiritual experience before I die. Your spiritual bent is so necessary even though I don’t know your particulars.

I’ve been reading Robert Whitaker’s books, Mad in America and Anatomy of an Epidemic, and I find them quite good. He doesn’t go over much of Jung’s personal and collective unconscious nor Hoffer’s psychedelic and nutritional work, but there’s so much density in his writings that he can’t possibly review everything. I’ll be looking out for your comments, I’ve noticed you post a lot, and I appreciate that.

Report comment

Hello evan, this is Larry. So we are coming here from very different places. I am trying to solve the problem of criminality on this planet. And you seem more interested in ideas about the psyche and personal experience.

While that is all fine and well, we are here to share our views and experiences, mainly, on the topic of psychiatric abuse and what can be done about it. The problem has a political component, an economic component, a theoretical component, and a practical component. (There may be others).

We are observing the phenomenon of a profession being driven, apparently, by a desire for profit (or even for the suffering of others) over excellence of result. The more cynical among us posit that this is the story of all professions, really. But these people are doctors. They are supposed to be bound by an oath to do no harm. Yet they participated in such atrocities as the extermination of millions by Nazis in Germany in the 1930s an 1940s. They have wounded or killed thousands (if not millions) around the world with barbaric psychosurgeries and electroshock. And today they freely use drugs to “treat” “illnesses” of the mind and spirit! (Psyche – spirit.)

We gather to learn what motivates this (I suggest that those who participate willingly in such practices are basically insane, and suffer from antisocial personality disorder, by their own descriptions of this disorder!). We wonder how it can be stopped (there is a leaning towards the idea of simply discrediting the entire subject). We occasionally explore alternatives (such as Open Dialogue, nutritional therapies, or maybe just leaving people alone). And sometimes we discuss underlying theory (which I insist, for example, must include the realization that we exist as immortal beings – a conclusion somewhat supported by the work of psychiatrist Ian Stevenson and his team – one of many ironies in this world).

While we occasionally stray into the world of mysticism, paranormal phenomena, and traditional healing practices, these topics seem to me to be well beyond our main focus. We realize that many other answers exist. We are trying here to address the dominance of this “answer,” which turns out to be a false and destructive one.

I hope this assists in orienting you to why I am here, and that it is a fair portrayal of why this website is here. Steve, as our moderator, may have points to add or modify.

Report comment

Larry, I agree and resonate with much that you say. I’m sorry I didn’t make it clear that I too feel there are systemic human right’s abuses throughout the mental health system, and that all immoral, incorrect, and misleading parts should be redressed–politically, legally, socially, financially, etc. I don’t like to group the entire profession together, and I have tried to point out that there are examples that I trust and respect. Even if the ongoing approaches of ECT, antipsychotics, forced commitment and drugging, etc. are similar to models of 50 to a hundred years ago, I don’t believe it is accurate to simply equate eugenics, sterilization, and lobotomy to how all things are done today, even if they sometimes share similar outcomes. And I don’t believe that all ongoing approaches are always immoral. We can’t claim that these are criminal in the sense that they are against the Law, even though we both recognize that very often they should be considered so and held criminally liable. These things are shared across communities, professional and societal (who are just as under the spell), and in order to change it, education and political pressure will have to be remedied, one step at a time. When you have a hospital of doctors, nurses, social workers, administrators, chaplains, etc. that all are interconnected along what is standard treatment in the in-patient clinic, then this education and change is certainly extremely difficult. We seem to agree on most of this.

There’s simply no way to convey to you my entire position and ongoing relationship with these things in a short format as this. It is easy to make many assumptions in this context.

I personally don’t reject the entirety of using chemicals–substances, drugs, macro and micro nutrients, and other physiological techniques–to influence the mind and spirit. I believe we are made of drugs (bio/chemicals), and that it is often an appropriate avenue to navigate psychology. But society is so used to a broken, corrupt, misguided, etc. use of drugs (so often called medicines) that many people reject them outright and conclude that they should be completely abandoned and have not done a spot of good for anyone at anytime. I support all withdrawal support groups, real informed consent and freedom of choice, a complete reimagining of how drugs are FDA approved, researched, and given as treatment. I also support the alternatives you mentioned such as Open Dialogue, nutrition, leaving people alone, religious freedom, as well as personality development through active imagination, mind-body work like yoga and exercise, and many of the other diverse approaches to getting right with ourselves and others. I personally think that, in general, a kind of all of the above approach is fully appropriate. In terms of being immortal beings, I will mostly leave that to you. As someone who has experienced a deterioration of personality/voice/etc., it becomes questionable and luxurious to me to assume that we are immortal, at least on this side of the transcendental fence. I advocate for quality of life at every level, including people with dementia, Parkinson’s, and Down’s syndrome. If immortality is part of that, then that’s fine with me.

I believe we have many areas where we overlap here, although obviously we have differences. I would point out that Mad in America does not appear to me to be all-encompassing group-identity that forms an ‘us vs them’. The ‘remaking’ of psychiatry posits not only not deconstructing it into a void, but also not only focusing on the abuse of conventional forms, but as you say allowing a furthering of health from all aspects. Your note that mysticism, the paranormal, and traditional’ practices are a minor focus is a little surprising given your previous emphasis on your ‘spiritual’ approach and your comment on being ‘immortal’. Perhaps I have misunderstood something. I have read articles on this website that have dealt with all 3, even though it may not have been the main focus. For example, how traditional Jewish worldviews influence present-day medicine, the commonly associated psychotic symptoms of telepathy, astral travel, speaking with entities, or more normalized subjects like dreams and voices. I do agree that overall the focus is on problems with mainstream psychiatry of the past and present and a collective effort and dialogue on how to proceed. These are many of the reason I have recently given $5 as a donation to this organization and have bought 2 books by Whitaker. I am glad you have tried to clarify your orientation. I’m not exactly sure why you think I’m focusing on psyche and personal experience, or that I have strayed from the themes of this website (other than unfortunately not referencing this article enough), except for the fact that your responses are based on only 3 of my comments. Frankly, focusing on psychiatric abuse and what can be done about (in all those components you mentioned) would be meaningless without dipping into psyche and personal experience. I mean, this entire site is chalk-full of expressing personal experiences and dealing with the ‘psych’ of psychiatry and the structures constellated around it. Surely you didn’t quite mean that. Or perhaps I expressed some things that were not strictly about the abuses and had something positive or neutral to say about psychiatry. I am sorry if I offended you, and if I could edit my long previous post, I probably would, as I was at first offended at some of your accusations and provocative questions.

I would appreciate you not trying to delineate what I can and can not say, and how it does or does not relate to your particular program. If the mediators would like to critically examine my posts and recommend that I tighten them up somehow, then I will definitely take that into consideration, as I ultimately don’t want to go against the grain unnecessarily of such a fine organization. I do hope to remain relevant and part of the process.

Report comment

Hi Larry, one last thing. I couldn’t edit my last post. I wanted to leave you with this:

Having said all that, I believe this will be my last comment in this section. I welcome your response, and I will consider it seriously. If you do respond, please help us both end our discussion with some reconciliation and peace. This is all taxing, and I’ve tried to make my points clear. Take care.

Report comment

Well, let me leave you with this, then. Because I’m no big cheese on this site, nor do I always see much support for my arguments.

I don’t know how old you are or how you were raised, but in my day it was OK to disagree, even quite stridently. It didn’t get anyone in trouble and “hurt feelings” were of no particular concern. Those customs are changing – but not, I think, because the new customs are better. So I hope you can see that I have no particular wish to tell you what you should or should not say or think. I’m only asking you to look at the same data I’ve looked at and consider it as you move forward.

I did not discover the “problem” of immortality by studying the Eastern traditions. I had heard about reincarnation, but skipped over it, as most people in the West do. But then I found that a researcher in the West had validated it. And the acceptance of this reality of life had led to an incredible amount of new information and a whole new set of healing practices. Later I found that others in the West were also taking this seriously. Even some psychiatrists!

I then took it upon myself to try to get others in the West, or any devotees of Western materialism, to consider the possibility of an immortal personality and what that could mean for human thought and life. It begins with the fact of past life recall. This is a simple, documented fact. The only question about this fact is whether you are willing to accept it or feel compelled to resist it. Many people in the West feel totally compelled to resist this fact. I don’t. I can’t explain exactly why. I welcome the possibilities that result from embracing this fact.

How many past lives, for instance, can a single person recall? I know an adept, Dena Merriam, who has recalled at least seven (all on Earth) and has written about all of them. I have personally met people who have recalled at least one. But I have seen research indicating that this recall can go way way back. We have, for example, Robert James’ work Passport to Past Lives. He reports finding past lives on other planets. So you see, if we have a way to access this past life data reliably, this begins to look more interesting. Merriam’s book makes it clear that mental conflicts in the present life can be related to long past experiences. And the other data I have seen only reinforces this. As I mentioned, there is even a whole healing practice based on these discoveries.

So, without going deeper into details, this is why I keep bringing this up. I see it as a huge blind spot in Western thinking that has forced us into a box we could easily free ourselves from. It has wide-ranging implications in human thought and practice. And it basically eliminates the need for psychiatry as we know it. So, I’m coming from the viewpoint that we already have a better answer, so let’s just get on with things. No need to spend endless years trying to “find the answer.” Let’s just implement the answers we’ve already discovered!

Report comment

Larry, ok, that is interesting, thank you. I feel you on your note on disagreement. See you around…..

Report comment

Yes Richard I agree it’s all rather complex. (I read the other thread which proved enlightening.) I have to admire the idealism of people seeking the abolition of psychiatry in toto, along with capitalism. But I’m not sure but that psychiatry will outlive capitalism. After all some people will still be driven to distraction by their experience of life. This I have little doubt will be true even if and when capitalism has outlived its usefulness if it ever had any. I’ve only recently come to this view in the light of climate crisis, another reality our ‘mental health’ brigades have identified for concern. In the meantime I won’t be holding my breath waiting for psychiatrys demise. I think there’s always going to be a need for an organised professional response to some people’s states of mind. But here’s still hoping your good selves or others efforts will at least inspire enough restraints to be put in place to limit the damage. Asking psychiatry to reform itself is obviously having no impact. You can throw all the ‘scientifically’ evidenced rebuttals at it you like it will have and has had no effect. They seem utterly oblivious to evidence of any kind while still managing to give every evidence of being decent professionals who sincerely believe in what they do. But maybe they will continue to and maybe more so lose some court cases. But so far they’ve managed to take these on the chin.

Personally I find no harm in simultaneously respecting the clear thinking (which I continue to admire despite my own muddled thoughts these days, my mind being addled by circumstance, experience and drugs) of some academics who have concern for how society responds to psycho-social distress, while still noticing that they all to often appear to pull their punches when called on to reject the basic functioning of psychiatry, and individualise responses. That and their own experience and understanding may explain what appear to some as cynical rejections of some stances articulated here.

Anyway I think the analyses of the problems being discussed here and the activism might bear some fruit eventually. It won’t be before time. Good luck and take care.

Report comment

OK: Foucault. “Foucault’s theories primarily address the relationship between power and knowledge, and how they are used as a form of social control through societal institutions.” – to quote Wikipedia, the ever-handy arbiter of “truth.”

Foucault is being pointed to (at least by critics) as one of the important theoreticians behind what has come to be known as “identity politics” and a range of other unconventional political tactics and policy ideas that we have seen play out in recent months, including such bizarre theatrics as the two months of violence in Portland, and “diversity” policies in companies and colleges leading to the firing of several people for, basically, voicing their opinions.

I see those who follow Foucault and his ilk as attempting to lead society in a more chaotic and disoriented direction than what it already suffers from.

From Rose: “The general lesson is that you should never look for origins, never ask ‘why’, but instead ask, ‘how did this occur?'” Does this strike anyone else as odd? The basic idea behind this school of thought is that all knowledge is relative to the function it serves. And there is an implication that no creation-point or origin-point for any knowledge actually exists, that all knowledge is basically just expedient propaganda.

From Rose: “We are in a very primitive state with brain interventions.” What exactly is he implying here? That psychiatry is basically correct, but is still too primitive to do most of us any good? Really?

Again: “The conflicts are not a problem; contest and argument are how things develop.” He follows the idea that all ideas and processes arise out of conflict. That social conflict is vital to the creative process.

On understanding psychiatry: “We must collaborate with psychiatrists from the point of view of critical friendship to understand how they think, to question them, and the weaknesses in their evidence and arrive at alternatives.” Why is he advocating this? Is this a requirement of the theories he believes in, or does he have other purposes for maintaining this “critical friendship?”

Rose is basically a brain boy: “Brain research has made fantastic progress over the last 30 years.” He thinks that if we switch our approach to his way of thinking, we will get better answers.

I am not a brain boy. I don’t want to be criticized for asking “why?” And the idea that knowledge is only created to suit the needs of power is useless to me if this means that knowledge not suited to the needs of power will continue to be ignored. I think real knowledge has a utility that transcends the short-term requirements of societies and their politics; that it can serve to elevate the individual to a place where politics are much less important.

Foucault came out of a time of deep intellectual apathy (nihilism in philosophy). While in some higher esoteric world, the concepts of the nihilists might apply, in this world they are ridiculous. They skirt the basic “laws” of human experience in ways that are dangerous and arrogant. They assume that the fate of the individual is to be consumed by the society he is a part of.

The “rationality” behind these schools of thought are complex and seductive. Rose, for example, seems to have some “right answers” about psychiatry. Yet he also seems to have some very wrong answers to life. If you want to live in a world where no one ever has to agree with anyone else, because “conflict creates knowledge,” then go with Rose and Foucault. I will attempt to continue to remind myself that we are living on Earth, not in Fairyland, and that we need games consisting of purposes, freedoms, and barriers, not endless chaos and criminality.

Report comment

I_e_cox: Thank you for your reply for a separate post. For some reason, there is no reply button under your or sam plover’s comments to me, and so I can’t reply directly for now. I don’t know if that’s intentional by mediators or a bug in the forum. I guess I’ll wait to see if it comes back and reply more fully then.

Report comment

It seems to me like I spend most of my time trying to find ways to feel a member of some group of people, like family, or maybe a church group, even a neighborhood. It seems like that’s the most urgent need I have as a social being. I can’t be secure without the signs and signals of membership. I could be labelled as depressed or anxious since those would be mental strategies to survive without my membership need being fulfilled. The signal of being accepted is feeling known. Others want to know my thoughts and feelings, and remember them. I wonder if it’s all really that simple.

Report comment

I think sometimes if we felt left out or alone as kids, it might even follow as a feeling,

some familiar feeling if we are in similar circumstances.

We might not remember the times we did feel that way as kids, or when we felt anxious.

Report comment