“If you teach a psychiatric resident that symptoms that occur during tapering cannot be due to withdrawal,” Dr. Giovanni Fava, a leading researcher of adverse effects from antidepressants, explained earlier this year in Psychiatric Times, “they are likely to interpret [the symptoms] as signs of relapse and to go back to treatment—exactly what ‘Big Pharma’ likes.”

The assumption that withdrawal from antidepressants indicates a relapse of depressive symptoms may stem from well-intentioned desire to reduce distress and suffering. But it is inaccurate all the same and led by clinicians who “have been taught only to think in terms of harmless medications.”

As Fava explains, “The term ‘discontinuation syndrome’ applied to antidepressants, versus ‘withdrawal syndromes’ compared with benzodiazepines, was a very smart method of the pharmaceutical industry to deny the problem. It is sad that most academic psychiatrists followed these leads. The evidence, based on systematic reviews and a large body of literature, is now pretty clear and the tide is turning. SSRIs and SNRIs may cause withdrawal reactions (new symptoms that were not present before), despite slow tapering; these reactions may be severe and do not necessarily subside in a few weeks.”

Fava’s clear-eyed explanation in Psychiatric Times was timely and significant because it intervened in the latest salvo in a two-decade effort to minimize iatrogenic (medically-induced) harm from SSRI and SNRI prescribing. The scale of the problem is worth considering based on prescribing numbers alone.

In the United States, according to the most-recent CDC data, one-in-seven (13.2 percent) of adults aged 18 and over used antidepressants between 2015 and 2018—more than 43 million adults. Use was higher among women (17.7 percent) than men (8.4 percent) and increased with age, rising to 24.3 percent of all women aged 60 and above. The 13.2 percent total for those years compares with 12.7 percent for 2011-14, when one-in-eight teens and adults was prescribed an antidepressant, itself a sharp increase from the roughly 8 percent of the population over the age of 12 prescribed the drugs between 1999 and 2002.

As one would expect, with the evidence-base for antidepressant prescribing expanding so rapidly to include tens of millions of people in just one country, a handful of distinguished researchers began to focus exclusively on the medical phenomenon. In 2012, Carlotta Belaise, a colleague of Fava’s and a frequent coauthor with him of papers challenging long-term antidepressant use, found that 58 percent of the patients “reported persistent postwithdrawal symptoms.” The paper was, however, based on a small number of patients (7 of 12) and could not be extrapolated reliably to indicate larger trends.

By October 2019, however, James Davies and John Read, researchers in London, determined from a systematic review of 23 published studies, surveys, and randomized controlled trials that antidepressant withdrawal affected an almost identical percentage of patients. In a conclusion that in the UK made national—then international—news, they extrapolated from these studies that “more than half (56 percent) of people who attempt to come off antidepressants experience withdrawal effects,” and almost half of those (46 percent) describe the effects as “severe.”

“It is not uncommon for the withdrawal effects to last for several weeks or months,” Davies and Read wrote in the Journal of Addictive Behaviors. One reason the systematic review made news: its conclusion directly contradicted guidelines on antidepressants issued by the American Psychiatric Association and the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Both agencies claimed at the time from much earlier, pharma-sponsored research that discontinuation issues are usually “mild” and “self-limiting” (resolved spontaneously in 1-2 weeks).

Davies and Read’s “Systematic review into the incidence, severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal effects” indicated a problem far-more widespread and persistent than regulators had acknowledged. They found much higher prevalence rates and far more serious, longer-lasting symptoms, with antidepressant withdrawal often lasting weeks, even months. Current guidelines, they noted, “underestimate the severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal, with significant clinical implications.” As such, the guidelines themselves ought not be considered evidence-based, a finding frankly remarkable in itself. The guidelines were at best misleading, at odds with the actual evidence, and “in urgent need of correction.”

“A systematic review” also made news because it upended long-standing assumptions that SSRI and SNRI antidepressants are broadly well-tolerated. Davies and Read determined from the 23 studies—themselves drawn from exhaustive searches on “MEDLINE/PubMed, PsychINFO, Google Scholar, and the bibliographies of 20 relevant papers”—that tolerance for the drugs was far lower than assumed, with discontinuation problems both more frequent and more chronic than two sets of national guidelines had advised prescribing doctors for two decades.

The revised data were meaningful because, according to the Guardian, use of antidepressants in the UK had “risen since 2000 by 170 percent, with over seven million adults (16 percent of the adult population) prescribed an antidepressant.” Whereas in Britain “about half of antidepressant users” were found to have been “taking the pills for longer than two years,” in the U.S. that number was closer to “five years or more.”

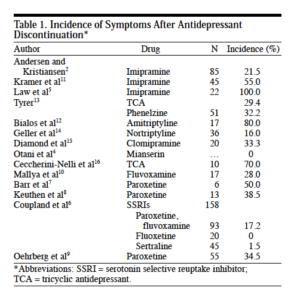

Davies and Read found overall that “withdrawal incidence rates from 14 studies ranged from 27 percent” to as high as “86 percent, with a weighted average of 56 percent.” The range almost exactly replicated and corroborated Rosenbaum and [Mauricio] Fava, who in 1998 had determined that among patients discontinuing antidepressants, 22 to 78 percent suffered withdrawal symptoms, depending on the SSRI in question.

Despite corroborating these earlier investigations—or perhaps because it did—Davies and Read’s systematic review became, in their words, the target of “some astonishingly fierce attacks on both the review and on the authors personally by prominent UK psychiatrists.” Perhaps predictably, criticism was strongest on social media and non-peer-reviewed blogs. However, in the same journal, London-based Sameer Jauhar and Joseph Hayes published a reply that, tellingly, was given the title, “The war on antidepressants.”

Jauhar and Hayes began by asserting, quite reasonably, “We agree that symptoms associated with withdrawal from antidepressants are important and we do not wish to minimise the impact reported by some individuals.” With their title however implying that Davies, Read, and others cited were somehow conducting a covert or full-scale “war on antidepressants” rather than, say, raising neglected safety concerns about widely prescribed drugs with a long and well-documented record of generating serious adverse effects, including from tapered withdrawal, they went on to dispute the principal findings.

They argued that “the interpretation that all such effects can be causally related to pharmacology is wrong and misleading,” though Davies and Read were closer to stipulating that most of the withdrawal effects registered were medically induced, following a tradition set by Lader (1983) and Rosenbaum (1998).

They faulted Davies and Read on methodological grounds, claiming that they put unreasonable emphasis on surveys and less on RCTs, making the “pooled incidence rate of withdrawal … significantly higher” and that the systematic review drew no distinctions over different kinds of SSRI. They also faulted Davies and Read for seeming not to track or mention withdrawal symptoms in people receiving placebo, and contended that there were “post-hoc decisions about the data,” including to exclude pharma-sponsored studies that would have set the rates for antidepressant withdrawal sharply lower.

Davies and Read responded with a vigorous rebuttal, arguing that Jauhar and Hayes not only misrepresented their methodology and mischaracterized their findings, but also had not properly consulted the pharma-sponsored study-summaries they faulted Davies and Read for not including. As the latter two pointed out, “None of the five so-called studies contain the incidence data they quote in their critique. To repeat, these five studies do not contain the very data that Hayes and Jauhar alleged we overlooked.” They continue:

Had Hayes and Jauhar read these so-called studies, even cursorily, they would have stopped in their tracks, as we did. Firstly, all five studies were written (either entirely or in part) by employees of Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals (who, in these studies, were researching their own drugs). Secondly, three of the five were not published as studies at all (so we can’t even assess their methodology). Rather they were published as short (300-word) research ‘supplements’ (i.e., industry-funded study-summaries) that some journals will publish in return for an industry fee.

“The obvious conflicts of interest and absence of clear methodology ruled out their inclusion,” Davies and Read concluded, including because “they failed to report incidence rates.”

More broadly, these and similar drug-sponsored studies had been responsible for minimizing antidepressant withdrawal all along. The selective reporting on adverse events—for instance, by labeling antidepressant withdrawal as “noncompliance” with study protocols and not counting negative results and negative trials—artificially lowered weighted averages and incidence rates. Falsely excluding them from antidepressant withdrawal data made them appear less chronic and debilitating than studies funded without drug-company support. Above all, to complain about the non-inclusion of drug-sponsored studies offering neither accurate reporting nor reliable methodology was, crucially, to miss one of Davies and Read’s key findings and contentions.

Read, Davies, and fellow researcher Michael P. Hengartner followed up in the journal Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences with a paper titled “Antidepressant Withdrawal—The Tide Is Turning,” detailing psychiatry’s protracted delay in recognizing antidepressant withdrawal as a full-blown, bona fide medical disorder. “The preferred narrative,” they wrote, surveying prescribing patterns since the early 1990s, is that the condition amounts to symptoms that “affect only a small minority, are mostly mild, and resolve spontaneously within 1-2 weeks.”

Yet SSRI and SNRI antidepressants continue to produce “remarkably high rates of withdrawal reactions … shortly after discontinuation,” with indicators even after careful tapering including “anxiety, irritability, agitation, dysphoria, insomnia, fatigue, tremor, sweating, shock-like sensations (‘brain zaps’), paresthesia (‘pins and needles’), vertigo, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, confusion and decreased concentration.”

Given these serious, well-documented effects, they point out, there has been a difficult-to-justify “dearth of empirical research on this important issue [antidepressant withdrawal] over the years.” “It took almost two decades after the [SSRIs and SNRIs] entered the market for the first systematic review to be published,” they affirm correctly. “More reviews have followed,” and those, in turn, have come to reinforce “that the dominant and long-held view … was at odds with the sparse but growing evidence base.”

By contrast, they point out, “almost 200 meta-analyses on the efficacy of new generation antidepressants [were] published between 2007 and 2014 alone, many with industry involvement.” To call that “disproportionate” would be putting it mildly. The publishing ratios tell us plainly that efficacy is a topic industry will sponsor and promote ad infinitum, while equivocal or negative results will be left unstudied and unpublished, revised by a switched outcome, or simply overwhelmed by the capacity of “the preferred narrative” to drown out all else.

Academic psychiatry, they write, has “long clung to the illusion that withdrawal reactions or discontinuation symptoms are minor problems that affect only a small minority and resolve spontaneously.” That has meant turning a deaf ear to the hundreds of thousands of online posts from patients, caregivers, and relatives, for two decades the clearest indication of adverse medical effects, themselves a direct consequence of psychiatry’s own prescribing patterns to tens of millions of people worldwide.

Considering the many years of silence and neglect of this issue, it is telling and frankly outrageous that rigorous, evidence-based efforts to correct this oversight could in 2020 be cast as a “war on antidepressants.” The hyperbole is itself a sign of how fiercely academic psychiatry has fought to evade appropriate and necessary focus on medically-induced harms, as psychiatrists—misrepresenting both sources and conclusions, and downplaying their many financial ties to industry—dismiss or publicly chastise those intent on documenting the drugs’ adverse effects empirically. Even to report on antidepressant withdrawal for the benefit of its millions of sufferers worldwide is represented as an attack on SSRIs’ and SNRIs’ most ardent and well-paid defenders, an outcome far from good for public health.

In the months since publication of these heated exchanges, NICE (the UK’s regulatory agency) has stated publicly that it is “committed to reviewing its position, held for over 14 years, that antidepressant withdrawal is usually mild, resolving over about a week.” Wendy Burn, former president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, has publicly demanded support for those struggling with antidepressant withdrawal and warned her colleagues: “Often what appears to be a relapse of depressive symptoms is actually a consequence of antidepressant discontinuation.” However, the American Psychiatric Association has yet to give any such sign, seeming to prefer silence and inertia to reform, because it puts off a serious reckoning with its own two-decade narrative about antidepressants as correctives to a “chemical imbalance,” a supposition long-since discredited.

“It reflects negatively on the whole of psychiatry,” Jauhar and Hayes conceded in their initial blog response to Davies and Read, “that there is not better, clearer evidence from high quality studies on the incidence, severity and duration of any symptoms related to antidepressant cessation.” Indeed. As Davies and Read noted justly in response, “this professional oversight, and its significance, is hard to excuse… The millions of people experiencing withdrawal effects cannot wait for psychiatry to determine whether they represent 50% or 57% of those withdrawing, or what will be the best methodologies to more precisely assess that. They need accurate information and proper support now.”

Im so tired of this shit.

Im so tired of this hydra which purports to be innocent.

I remember perfectly my first ad withdrawal.

I was 16. So innocent and so wrecked (tho i had the chance not be drugged during my childhood, only the teen period) I had confusion, lethargy and severe cognitive problems for months (before being misdiagnosed and restarted on ad, lol). It completely ruined my graduation year.

They have no fucking clue what their experiment entail.

It is time that they are dragged onto a public place, have their mouth forced open, and stuffed with their brain bullets.

It its time that they learn.

After having lived all that I lived at their hands, it is incredible seeing them more than a decade later still casting the denial refrain.

Report comment

Exit I think they already feel demeaned at their core. They took SO many years of trying to be

a doctor, only to see that it is a very menial job where they spend the rest of their lives in a prison,

trying to “mean” something, only ever being “understood” through other shrinks, both slinking around, knowing they are lying to each other and thereby to themselves.

Cults are powerful. It needs the adherents to keep up the lies, against all odds.

Report comment

Thank you, Exit. I agree. I wanted in this and recent posts to document a decades’ long, profession-wide *effort at* denying the existence of antidepressant withdrawal, including to emphasize that the effort *has* failed, importantly because of years of pushback and documented evidence. I wanted readers to see for themselves how even letters published *in the psychiatric journals* themselves failed to make a lasting impact at the time—that’s part of the longer history and I’d say it’s crucial that it be recorded as well as reintroduced into discussions today, precisely to ask: How *is* it that so many in the profession managed to turn a blind eye and a deaf ear to something so serious and so widespread?

Report comment

[Duplicate Comment]

Report comment

Thanks Christopher.

Sorry I will not buy, and neither does psychiatry even, that they were not aware of the harm.

One must be a REALLY BAD psychiatrist not to be able to identify drug harm. One is an even

worse psychiatrist to keep prescribing and denying. No medical knowledge, so why are they

playing with chemicals.

Which of course proves that they cannot identify anything, and can’t be relied upon

to give expert witness or testimony.

Since they lie to protect themselves, ALL “data” is highly suspect, manipulated and skewed.

Report comment

Thank you, Sam, for that dose of sanity. I needed it.

Report comment

100% Sam. Thank you. Yes, the point isn’t to dispute that they didn’t know; it’s to document—clearly, for all—what they preferred to *not* know and to pretend collectively could be ignored. It can’t be, and I wanted to help convey why.

Report comment

It never hurts to keep pointing out the collective BS.

I think behind the BS, are purely personal reasons for

each individual shrink, who does not want to lose

his imaginary prestige. I think it becomes even more

driven when they realize it is not such a prestigious enterprise.

There is no other explanation. If I worked for a crappy company

but had carved myself a little niche after years of studying for it

and buying their wares, I might not want to give up title or reward.

Report comment

“These processes may also propel the illness to a more malignant and treatment-unresponsive course, as with … bipolar manifestations or paradoxical reactions.”

As one of the millions and millions of people who had the “bipolar manifestations” of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome blatantly misdiagnosed as “bipolar,” according to the DSM-IV-TR. I do appreciate you trying to educate the psychiatric industry about the iatrogenic adverse and withdrawal effects of their drugs.

And please do also help educate them regarding the common adverse effects of their “bipolar treatments,” the “schizophrenia” drugs, the antipsychotics / neuroleptics. Since those drugs can create the negative symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome. And they can also create the positive symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via anticholinergic toxidrome.

In other words, the two “most serious” DSM disorders, bipolar and schizophrenia, are iatrogenic illnesses, created with the psychiatric drugs. I realize this a a bummer for the psychiatric industry, but it is truthful information that needs to be made clear to the psychiatric practitioners, and their many DSM deluded “mental health” and social worker minion.

“That’s alright, that’s okay, you’ll be working for us some day.” Go ethical Northwestern professors, and thank you for helping to expose these psychiatric industry crimes, Christopher.

Report comment

The “almost 200 meta analysis have been published alone” is laughable. A meta analysis is a study that looks at other studies and reports their average results. All these meta analysis are of the same industry funded studies. They aren’t new; they are the same bad science junk that has been debunked. They have the same pro-drug flaws such as multiple instances of cherry picking, withdrawal, unblinding, outright fraud, short term length, and conflicts of interest etc.

Report comment

This “clear eyed explanation” would have been “timely and significant” a few decades ago. Not now.

“I’m so tired of this shit.”. I second that.

Psychiatry should take responsibility for what they’ve done including launching a huge information campaign so that every therapist, GP, family member — everyone that a person who’s been harmed by the drugs is now disbelieved by – knows that everything Psychiatry said before about these drugs is completely false – no one had a chemical imbalance (at least not one that the shrinks discovered), the drugs were never safe or effective, and people are suffering. Psychiatry needs to own up or shut up.

Report comment

“I’m so tired of this shit”, I third that, Exit and Katel.

Here we go loop de loop.

Report comment

Agree. That even well-documented evidence about antidepressant depressants could be couched in 2020 (!) as a “war on antidepressants” also tells you exactly what the challenges have been and just how many remain.

Report comment

Thank you for responding, and for doing what you are doing to make the truth known while others are actively trying to suppress it still.

Report comment

I just hit the wall three years in to my Wellbutrin taper, after 25+ years taking it as prescribed. Debilitating symptoms after small (one percent) cuts lead me to conclude that I am experiencing systemic neurological injury of my CNS, PNS and ENS rather than “protracted withdrawal”.

Report comment

I’m sorry, Lauren. I believe you, if that means anything. I think I may be experiencing something of a permanent/chronic nature also, in terms of psych drug damage. I’ve lost basically everyone and everything and my body is in survival mode. I try to explain it to the couple of people who still speak to me, and they say, “So then, what’s the solution?”. It makes me so angry. Like I’m supposed to know the solution is to what the drugs did that no doctor I’ve ever seen believes me about. Somehow that is our responsibility when we were the ones who were lied to by people who took an oath to do no harm.

Report comment

Thanks for this article and your recent series about the history of antidepressant withdrawal, Chris.

I think one very important factor for the misrepresentation of antidepressant withdrawal syndrome since approximately the mid-1990s is that the pharmaceutical companies and psychiatry saw that the new-generation antidepressants were much better than the old antidepressants — MAOIs and TCAs — with which they had to work before. The new-generation antidepressants had fewer adverse effects *on startup* and dosing was not as tricky. In comparison to MAOIs and TCAs, “tolerabililty” of the newer drugs was much higher.

This made the mass-marketing of antidepressants possible. For its part, psychiatry saw the opportunity to move from a specialty treating a few people to a more central role in medicine treating millions.

This was even though 25%-30% of new-generation antidepressant efficacy study subjects quickly dropped out within a few weeks because of intolerable adverse effects. (This may indicate a substantial population, possibly defined by genetic characteristics, upon whom the drugs were not trialed at all before marketing. These individuals, however, are being prescribed the drugs like everybody else.)

Coincidentally, it’s long been known that 25%-30% of those prescribed antidepressants quit them within a month (Jung et al., 2016, “Times to Discontinue Antidepressants Over 6 Months in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder.”). When this was recognized in the mid-’90s, pharma and psychiatry united in stressing the important of “maintenance” beyond the startup period *despite adverse reactions*. This led to a well-funded effort from pharma to train doctors in techniques to keep patients on the drugs until they “work”, which supposedly takes 6 weeks. This campaign included presentations at psychiatry meetings and articles in psychiatry journals, e.g. Delgado, 2000, “Approaches to the Enhancement of Patient Adherence to Antidepressant Medication Treatment.” (in a pharma-sponsored supplement to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry).

It’s also long been known that withdrawal risks increase after a month of regular antidepressant ingestion. A successful “maintenance” effort greater than 6 weeks would make withdrawal syndrome inevitable for some large proportion of patients. (We know now that experiencing withdrawal symptoms discourage people from trying to go off.) In 2006, Maurizio Fava (brother of Giovanni Fava; Maurizio went into consulting on drug development for pharma) estimated the rate of withdrawal syndrome for new-generation antidepressants to be 50%, in comparison with ~40% for TCAs. Therefore, the specter of withdrawal syndrome might diminish the antidepressant-based mass-market expectations of both pharma and psychiatry.

With these expections, it was important to both keep people on the drugs until they were hooked and minimize the risk and discomfort of withdrawal syndrome. Psychiatry participated enthusiastically in this. Lilly and then Wyeth, respectively, paid for “expert consensus panels” and hefty supplements in Journal of Clinical Psychiatry in 1997 and 2006:

Schatzberg, A. F., P. Haddad, E. M. Kaplan, M. Lejoyeux, J. F. Rosenbaum, A. H. Young, and J. Zajecka. “Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Discontinuation Syndrome: A Hypothetical Definition. Discontinuation Consensus Panel.” The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58 Suppl 7 (1997): 5–10.

Schatzberg, Alan F., Pierre Blier, Pedro L. Delgado, Maurizio Fava, Peter M. Haddad, and Richard C. Shelton. “Antidepressant Discontinuation Syndrome: Consensus Panel Recommendations for Clinical Management and Additional Research.” The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67 Suppl 4 (2006): 27–30.

It is remarkable that pharma saw it necessary to do this twice, both star-studded supplements communicating the same message: That new-generation antidepressant withdrawal syndrome was mild, transient, self-limiting, and could be expected to last only a couple of weeks and *anything after that was relapse*. Through various avenues, not the least Pharma-sponsored medical training programs and CME, this became the dominant narrative.

Those are 12 leaders of psychiatry who co-authored those 2 papers alone. After the 1997 supplement, Peter Haddad, an expert in adverse effects of psychiatric drugs, published a half-dozen papers about antidepressant withdrawal syndrome in which he took pains to state that there were exceptions to short, mild withdrawal, with some people experiencing severe and prolonged symptoms. In personal correspondence with Richard Shelton, coincidentally at the same time the 2006 supplement was published, Dr. Shelton acknowledged to me that some people do indeed experience severe and prolonged symptoms.

So those are two of the “expert consensus panel” who knew that those JClinPsych supplement articles were not telling the whole story. (On my birthday in July 2006, when I was 2 years into paroxetine withdrawal syndrome, Owen Wolkowitz, a UCSF faculty member and colleague of Schatzberg’s, verbally told me that of course Schatzberg knew about protracted antidepressant withdrawal syndrome, all the leading psychiatrists did.)

So how deliberate was it that psychiatry, a decentralized specialty disavowing defined leadership and highly resistant to enforceable guidelines, denied the larger danger of prolonged antidepressant withdrawal syndrome? Does the complicity of maybe 10 or 50 or 100 psychiatry thought leaders indict the whole profession? Why would an ordinary general psychiatrist, knowing that withdrawal from TCAs, MAOIs, and addictive drugs can be brutal, assume that antidepressant withdrawal syndrome would pass in a few weeks, and any symptoms after that, no matter how bizarre, be “relapse”? What is wrong with this profession?

Report comment

Excellent Alto.

Report comment

https://www.zerohedge.com/medical/antidepressants-linked-rise-superbugs-new-study-reveals

Report comment