I am a woman who fully identified with the label bipolar for almost 20 years and, according to psychiatry, rightfully earned it with four involuntary hospitalizations. Early on, I was given no other language besides brain disease and unbalanced chemistry with which to understand the altered states and despair I experienced. When I look back honestly on the very recent past, I see that I used the identity of bipolar like a brace around my hard-to-manage mind, to hold it still, to teach it where it could and could not go—where I could expect it to be at any given moment. Even what I could expect from myself and my life.

There were books about bipolar I could read, lived-experience narratives like Kay Jamison’s An Unquiet Mind and clinical descriptions with observable rules and patterns that felt somehow reassuring, even as they were mostly defined by struggle and suffering. I understood myself as a woman who had extreme mood swings—even if the highs never quite exactly fit the bill of mania. I was a woman who heard voices and saw things sometimes, things that had no meaning other than illness. I was a woman who needed psychiatric drugs to survive in this world as it was. I was a woman who would never heal. “There is no cure,” was something I heard at 21 when I was first diagnosed and many, many times afterward.

And perhaps the word bipolar saved me for a time. It did a few things for me. It got me medical care. It got me the kind of care that our society has to offer for what I experienced. It drew doctors to me, doctors with tools to ease my pain—in a way—even if these tools circumvented the true root of my suffering. And it even drew validation of that suffering, corroboration by people with degrees and authority. Yes, you are in more pain than most. Yes, everything is too hard and isn’t that hard for everyone. Yes, your emotional pain feels wrong and we think it’s wrong, too. Yes, your pain is real—so real.

But for me, this was a twisted and dangerous form of validation that took far more than it gave. The label bipolar validated that I was suffering, yes, but it was a bargain that asked me to surrender my understanding of my suffering as “normal” and replace it with a belief that it was the result of an “illness.” It asked me to see my suffering as unreasonable, a result of a deformity within my body. It took away my ability to see my emotional states as the result of what had been a tough youth and an even tougher young adulthood, a result of my excessive use of marijuana and alcohol and of untreated trauma, by taking away the language I needed to describe it.

Strangely, I never truly fell for the illness model in the way I was meant to. I went one step further: I drew it closer to me and thought “I” truly was broken. My mind, body, and soul—because in the end, these three things are so hard to disentangle within one’s identity. A point many practitioners miss when dispensing these labels. It was the application of this strange, twisted, and dangerous “validation” to the surface of my suffering that let self-hatred, denial, and suppression seep deeper into my every insecurity about “not fitting in” and experiencing the world differently. Leading, ironically, to the endless cycle of pain the diagnosis was meant to lessen.

To me, there seemed nothing truly valuable about being bipolar, either, except perhaps that I had the luck of being an artist, too. There was some romanticism, at least, in that. I was the crazy creative. But this was not something of much real value – as artists themselves are seldom valued or supported in our culture.

Bipolar was a map. It was scaffolding on a building, it was a straight hallway to walk in a maze of a mind. There were numbers that insurance companies understood. There were instructions to follow that, if I didn’t think too much about them, were at least something I could do besides lie in bed, or stare down a bottle of pills trying not to die. It was a kind of hope—something that maybe my friends and family could use to explain me, explain my anger and sadness, explain why I called in the middle of the night and begged to come over and hide, to avoid my psychiatrist, the police and the hospital, on one of the many nights the burden of all this was too much and death seemed an easier thing. I was bipolar. At least that —if only that— made sense.

It helped me. And it helped them, my family and friends. It did. Until underneath it all I started to see that in those straight hallways, behind those walls and braces, with those directions and instructions—I had nothing. No power. No choice. No freedom. I was afraid to let my mind wander into uncertain, ambiguous places such as the spiritual or the more wildly creative, for when it did it was like being in some dark alley, anticipating an attack. My mind was scared of itself, its full potential. I had nothing but illness, wrongness, and brokenness as a framework to understand my mind. And most importantly, I had no path to healing, because I was told bipolar was incurable. I had no way out of the pain. Not even the drugs they promised would help me, or do anything more than make my suffering worse.

I was done for. All the studies said I would die, I would die soon, and I would suffer till then. Either from the presence of the drugs and their effects on my body or from the lack—the lack of feeling, the lack of choice—the presence of which, I learned, would be exactly what helped me heal. All the studies and all the stories said I would die, or decompensate. Disappear somehow, in some uncertain circumstance where everyone I loved would wonder: Was it their fault? Did they not try hard enough? Did I not try hard enough?

I would die bipolar, they said. I would die on psychiatric drugs. And I woke up to this prescribed narrative of my life I had been handed as I looked closer at the rules. What I was told was the way it was and always would be. The reality I was meant to swallow and accept. The pills I was meant to swallow. Everything I was meant to believe about myself. I started to look at my mind, my dreams – my visions, my voices, and my suffering, especially my suffering— without fear or rules or braces, and these parts of myself began to speak to me of a path to healing.

I listened to, and befriended, my mind as it tenderly wandered off the paths laid out for me. Oh, yes, I was afraid. The depth of my sorrows have always been great. The confusion has always been crushing. Before I fell into the sedation of psychiatric drugs, even while I floated in that ocean of chemicals, all the while, the realities of life were still so massive and confusing. Every little bit of it didn’t make sense. No sense at all. And it hurt. It was painful. Every inch my mind wandered. Every door I opened labeled disease. Every door labeled danger.

Every step was fraught with fear. Will I be abducted, drugged, gaslighted, coerced, imprisoned if I take a wrong step? But by this point, I had so many doubts about this framework handed me called bipolar—this map—their certainty, and rules about me. Some part of me knew they were wrong. So I kept stepping out of line. Way out of line. I no longer believed my psychiatrist had the answers to my suffering and began trusting myself that I could manage, I trusted my own body and research around withdrawal and went slower and more cautiously than any psychiatrist would have suggested. I explored and integrated spiritual ideas that were so often off-limits for someone with a history of altered states. I started to face the trauma that therapists either denied, as its roots lay in their industry, or avoided because they feared it would destabilize me. Each time I wondered if I could do it. If I could be OK without these rules, these drugs and doctors.

One message that came with my psychiatric label did offer a kind of comfort throughout my process of emerging from it. All those years ago, when I was hospitalized, put on psychiatric drugs, and labeled bipolar, one bit of wisdom, although essentially misguided, stuck and evolved into something helpful. This biomedical model, which allows people to understand that their suffering is beyond their own control, not their fault, just a result of so-called faulty chemistry, is often such a relief. Because in truth, beyond the framework of biology, it is mostly true for all of us.

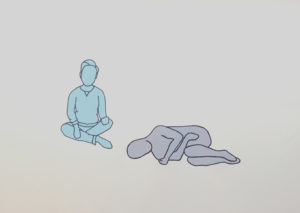

In studying Buddhism, I’ve found that despite the fact that I no longer subscribed to the “bipolar” diagnosis, I still accept my lack of control over suffering, just in a different way, within a different framework. In that resistance to it is the problem. All these attempts to eradicate something so essential to human life instead of lending compassion and acceptance lead directly to making it more and more unmanageable.

There is a story in Buddhism called “The Second Arrow,” which essentially says that pain is inevitable, while suffering lies in the resistance to and judgment of it. I believe that the idea of control is an illusion far too often enforced upon us in our society. So, when a framework appears that relieves one of responsibility, whether it be through an erroneous scientific idea or the wisdom of a spiritual one, the initial result is the same: relief. But as with truths embedded in any broken system, the end result of an erroneous scientific idea can be deadly. It is frightening to realize that an industry founded on “healing” suffering lays claim to this more spiritual idea of the essential lack of control in our very human existence.

As I continued my journey, I also found that the fear of these feelings of suffering —my judgments of them, the inner talk of “you shouldn’t feel this way” or “you are weak to be feeling this” —intensified them, making them more and more unmanageable. The message of psychiatry, intended or not, was to be afraid of one’s “illness.” This was particularly true of the voices and strange experiences. My fear of them, reinforced by psychiatry’s aggression against them, became the root of what made them a problem, but as I invited them in as parts of myself, they lessened and became more like teachers. I used my art and writing to give them voice—I finally let my mind free. And with that, regained a self-image of wholeness, worth, and beauty.

I started stepping off all of my psychiatric drugs in September 2019. Starting with Lexapro, then Latuda, then Lithium, Lamictal, and Vraylar. One by one. After coming off Latuda, my suicidality, which had persisted for years, disappeared and I was galvanized. The bargain I had made with the bipolar label had nearly killed me. But I had survived the psychological and physical consequences of a psychiatric label that are so often overlooked.

As I began my taper of the final drug just this past November, and just as importantly, as I had truly shed the brace of the bipolar identity that had become a prison, one of my best, oldest friends told me on the phone that my voice had changed. A voice teacher, she said she could hear life it in again. She said, “I feel like I am talking to another person. I mean it’s you,” she said. “But, now, it’s really you.” And we cried together because it felt like I was finally free.

“This biomedical model, which allows people to understand that their suffering is beyond their own control, not their fault, just a result of so-called faulty chemistry, is often such a relief. Because in truth, beyond the framework of biology, it is mostly true for all of us.”

Wonderful Karin. Thank you for this rich piece.

Great to hear that you saw there was much more than one framework. We can either try to understand ourselves and others, or allow others to do our understanding for us.

Report comment

Thanks so much Sam! And what you say is absolutely true.

Report comment

So many people are labeled “bipolar” when, in reality, they have a histamine level that is too high, or too low, or they have adrenal glands that produce too much adrenochrome (and they produce even more of it when they’re under stress.). They might have too much copper in their body, proven to be cause of psychosis since around 1950. A lab test (which I asked our family doctor to order) showed that my “bipolar with psychosis” son had a histamine level that was simply much too high. I gave him the “nutraceuticals” his BIOchemistry needed to get his histamine level down. As it came down, I slowly tapered him off of three daily antipsychotic drugs. He hasn’t needed psych drugs in years. He has also been treated with NAET (acupuncture) and homeopathy. So I really have a beef with anyone labeled “bipolar” because the real diagnosis is more likely an elevated histamine level called “histadelia;” or the person has a level that is too low, combined with a copper level that is too high which is called “histapenia.” Someone with elevated adrenochrome is “pyroluria.” Yet these illnesses are all labeled “bipolar” by psychiatrists who have no clue how to cure anyone, just push drugs for Big Pharma. I know this: if you don’t know what is causing an illness you’re never going to cure it. And what is the one subject that psychiatrists evade at all costs? Why, yes, it’s what is causing the illness. American-style psychiatry is mostly fraud, in my opinion. It brings in a boatload of profit to the psychiatrists and drug companies – but it cures no one.

Report comment

Beautiful article Karin,

These labels are too much trouble (I think)!

Report comment

Thanks for the kind words.

Report comment

As a fellow artist and no longer “bipolar” stigmatized person, I couldn’t agree more. Shedding the BS “bipolar” stigmatization, and getting off the psych drugs, is a good thing. I’m glad you, too, escaped the insanity of today’s “invalid,” “unreliable,” “bullshit,” systemic child abuse denying and covering up, psychiatric system.

Report comment

It seems society has never really figured out how to truly honor artists, from childhood on up into adulthood.

Report comment

You are right. I have heard good intelligent people with excellent ideas on almost everything else speak of taking the arts out of the schools. But, they forget without the arts there would be no cathedrals, no hymns or Christmas Carols; actually no buildings for homes, no tv shows or movies to watch, no Christmas, Birthday, Mothers Day Cards, etc. Life would be so bland and that which they take for granted would not be there. Oh yes, we would also be “naked as jaybirds” and completely shoeless. And hungry for good food for nutrition. No Joy anywhere. Not only that we might all go extinct. Maybe not even the Bible. Why isn’t God the Greatest Creator Ever?

Report comment

So true my friend. I have a hard time explaining this to most people. But I always try!

Report comment

Yes, it is the drugs that make you sick. It is the drugs that alter your brain and body’s biochemistry and make you a hostage to the psychiatrists, etc. and yourself. In my cases, I started to receive diagnoses that I was either “bipolar” or had “schizo-affective disorder” and I was told I had “severe and persistent mental illness” after they had pumped these drugs in to my brain and body. It is also a lie. In my opinion, the DSM Manuals list of diagnoses are all basically descriptive of the person’s brain and body’s “reactions” to these evil drugs. I was never “sicker” than when I was on the drugs. But, unfortunately, now my “disability” is the damage that these drugs did to my brain. I say brain because, it is the brain that is the steering mechanism for the whole body and is the real target for these drugs and thus explains the tyranny, torture and terror these drugs cause. Thank you.

Report comment

“In my opinion, the DSM Manuals list of diagnoses are all basically descriptive of the person’s brain and body’s ‘reactions’ to these evil drugs.”

Well, at least in regards to the “bipolar” and “schizophrenia” diagnoses, this has largely been medically proven. Robert Whitaker did a good job of pointing out that the “bipolar” symptoms are most often created with the ADHD drugs and/or antidepressants, in his book “Anatomy of an Epidemic.”

And the “schizophrenia” drugs, the antipsychotics/neuroleptics, can create the negative symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome. Plus they can create the positive symptoms of “schizophrenia,” like psychosis and hallucinations, via anticholinergic toxidrome.

Report comment

Psychiatry tells everyone those with “mental illness” are defective and have biologic abnormalities. That they will be “ill” and suffer forever. In a sense since almost all people with a “mental illness” take chemical imbalance causing psych drugs this is true. A fear filled self-fullfilling prophecy in more ways than one.

An often reply when I’m telling people how psych drugs cause only harm is “you are fear mongering.” Pscyh defenders utilize projection as much as a movie theater. When they are attacking anti-psych it’s more likely than not that they are projecting.

Societies view and opinion on what people with these psych labels are like is not based on what these people are actually like. It’s based on what they are like when they are addicted to psych drugs, or in withdrawal. Many of the stereotypes, traits, and outcomes for people with these labels are effects from the drugs.

Stereotypes such as having movement disorders, tobacco use, drooling, unemployment, cognitive impairment, early death, brain damage, apathy, suicide, an inability to feel pleasure, and a lack of motivation are all caused by neuroleptics. Even the symptoms these drugs are said to reduce are increased by the drugs.

It becomes a feedback loop where people take the drugs because they are lied to about the effects and about having a chemical imbalance. The shitty outcomes afterwards then become proof people with psych labels are defective and ill. If those people quit the drugs withdrawal becomes more proof.

Report comment

The tragic irony you state is when you tell people psych drugs cause only harm; they claim you are “fear-mongering” and yet, it is that very “fear-mongering” that gets innocent people “hooked” into these drugs and therapies; creating a dangerous, destructive, and unfortunately, sometimes deadly lifestyle. I say lifestyle, because, your life revolves around the drugs, the therapy appointments, and any other associative activities like “adult daycare” or “daycare therapies” or whatever they cook up, that of course, doesn’t work or perhaps not really meant to work. I learned there is a little “cult-group” that lives their lives based in this travesty and all they do is go from drug to drug, therapy to therapy, psychiatrist to psychiatrist, etc. A life of meaning that in reality makes you mean nothing and thus you become meaningless. Thank you.

Report comment

Yes, I agree on many fronts. And I can’t pretend I don’t have first hand experience with the truth of this.

Report comment

So happy and energized by Karen’s about face. Love the best friend crying with Karen over her “real” voice. I imagine though she was a voice teacher, she wasn’t the only one to notice the change. Wonderful. I had a very similar history, and found a better way to gain access to my severe trauma, though that came over 35 years ago when Eastern Philosophy became prominent in my life. I mistrusted doctors so much by then, I one day went cold turkey, not a good idea, so I’m very glad Karen took her proper time getting off her presciption drugs. For me, my sense of well-being took decades longer until the diagnosis of Complex PTSD and its cognitive behavioral treatment assisted further in cleaning out the old closet. I’m now elderly, and no longer fight with myself. Proud to be more than a survivor. Karen’s is another success story that I so enjoyed.

Report comment

So glad to hear your story. And that you are like you say, “more than a survivor.” Thank you so much for sharing. Much love.

Report comment

You survive a psychiatric labeling by rejecting it, both inwardly and outwardly. There’s no middle ground.

Report comment

Thank you so much for this article, Karin. I have tapered off Seroquel, Gabapentin, and most recently Lexapro. i am down to lithium and Lamictal. I am fearful of tapering off these last two worried that I may experience a manic or depressive episode. My lifestyle has changed immensely (for the better) since my diagnosis in 2014, yet I remain worried about these last two “core” medications. Did you experience any similar feelings, and how are you guarding yourself against another episode? Or do you believe a bipolar “episode” was the result only of medications and not any other factors. Given that I had “episodes” before medication, I struggled to believe fully that medication only is responsible, more likely a history of trauma and alcohol use (though I had been taking Lexapro for a good eight years before my first manic episode that I know of.) I admire your courage to fully taper off all medications. Thank you for sharing your experience.

Report comment

I have taken all the drugs you have named, except, I am not sure if I have ever taken Lamictal. I took Seroquel very briefly and took Gabapentin very briefly and remember complaining to the psychiatrist it was useless drug that didn’t work. Seroquel was actually about the last “anti-psychotic” prescribed to me. It gave me terrible headaches and my last idiotic psychiatrist harassed me about taking it as she prescribed. Her words wee nothing but abusive. However, about Lithium; I was probably on that particular drug the longest, as I was on it from about 1991 until 1995 (I tapered off of my own that time) and then again from about 1998 or 1999 or so until 2015. I think there was brief break for depakote. Lithium can cause lithium toxicity and you may not even know it; especially, if you have been on it awhile. When I did come off Lithium, I did not ever experience manic episodes. I question manic episodes anyway and wonder if many aren’t drug induced or psychiatrist induced. Like I have noted earlier, I was abruptly taken off all my drugs, except Lithium, because I literally became nearly comatose as I could not be awaken. After that they tried this and that drug until two years later, I could take no more. There is one major point I can tell you about my experience after being off Lithium, it is about salt, heat, and electrolytes. When they first put me on Lithium, they warned me against a salt restricted diet, getting overheated (many drugs have heat issues) and making sure I had something like Gatorade readily available to drink. After all those years on Lithium, I can not do without salt. I must salt everything. If I don’t I have cramps, sometimes in my legs. I also must drink about 20oz of Gatorade daily and if stressed, I must drink at least another 20oz. Luckily, as for salt, I have no issues with water retention like some people do. I didn’t previous to my being prescribed Lithium. The issue with stress is that due to the Brain Injury from all the drugs, I can get stressed pretty easily and at times quickly. I think, it’s very important to realize, that getting off the drugs will save your life; but, you must adapt your life after getting off the drugs. In a way, you will forever be their prisoner. Yet, I would like to add this: Is it worth it? Despite everything, it is worth more than anything in the world. To survive this and live is a monumental victory for you and for everyone so abused. And each day, despite it all is a day of victory and of joy; even if I don’t always feel that way; because now I know I am human, I belong to God and no one can ever take that away! Thank you.

Report comment

I found being psych drug free a victory also. I had no idea how the drugs had altered my perception behavior and thinking. It took determination to become drug-free and to adjust to life no longer being monitored by psychiatry and psychiatric drug. I was able to read books again to do hobbies I had put aside and to make awesome new friends. I am so thankful for this.

Report comment

Hi Trompster,

Thanks for sharing your story. And thank you so much for the question. The more I share my story, the more I get this particular question about fending off more episodes. I think something you said is important, and was really important for me: that I’ve made major life and even psychological changes (like quitting pot years ago, alcohol, and eating better, different supplements – like NAC – which actually seems to help a lot, and really digging into resolving my trauma around family and hospitalizations.) I feel like this strengthened me and made episodes less likely. But, it all is a mystery in some ways. I too, had altered states etc before medication, but I truly believe these are natural responses of the brain to trauma in some cases. I guess as the trauma resolved and the exacerbating chemicals (pot, psychiatric drugs, etc,) were removed from the equation, it was a much safer environment for me to get off everything. I’m still on a tiny bit, tapering off Vraylar now. It’ll take me a bit. But, it’s been one of the more difficult – even if it is such a small dose. My voices and everything really started relegating themselves to dreams/falling asleep a while back, the suicidality was mostly due to the Latuda and just…what it’s like to be a psychiatric patient for 20 years, and my “manias” were never (except for maybe once) really textbook. I wish you so much luck, look, the thing is trust yourself, build in some safety nets and give it a go. you won’t know until you try. But I totally get the fear around it, so much. Sending strength and solidarity.

Report comment

I forgot to add to my last comment that either before after the Lithium I did not have trouble with not only water retention or high blood pressure; except the once-in-a-while “white coat type of blood pressure.” After, I came off the “benzos” and the other drugs so abruptly and with some other bizarre treatments they used to hide what really happened; I would temporarily show a little high blood pressure; but there questions about the instruments being used. There was one odd thing during that time is that my heart beat so loudly and continuously, I felt like it would jump out of my chest and I had insomnia for about a year. Of course, when I went to the doctors and they put on some 24 hour monitor test, they said “Nothing to see here, sweet lady.” But, that’s was resolved by me without their assistance some time after that. Thank you.

Report comment

Hi, rebel. Thank you so much for taking the time to share your experience. I’m glad you were able to get off the lithium successfully. As far as the many psychotropics go for bipolar disorder, lithium appears to be one of the more benign as far as psychological health, perhaps not other organ systems as you mentioned. I regularly get blood work and have not had any problems so far, though I do know lithium does constrain my ability to really experience pleasure. I could win the lottery tomorrow and muster a smile. Thank you again!

Report comment

I am not sure how long you have been on lithium; as you did not state that information. I appreciate your being grateful for my taking the time to share my experience. I am glad that you keep up with your blood work for lithium; but, I believe that is a requirement as per the doctors. I am also glad that you have had any problems so far. However, I will not be convinced that lithium is a benign drug in any sense of the word. When they put me on lithium, the first time, they set me down and explained what I could and could not do while taking lithium. They also gave me a sheet of paper that I was to carry around with me while I was taking my lithium. In fact, back in the 1970’s lithium was still such a controlled drug, in hospital and other pharmacies, it was locked in a secure place. That has changed since then. However, you have to ask, if lithium were so benign, why must you take a blood test at regular intervals to determine lithium levels. Lithium toxicity still remains a problem and can be for some life-threatening. In the world of psychological type drugs, there are NO benign drugs! Thank you.

Report comment

Topforexvn mang đến cho người đọc những đánh giá sàn forex chi tiết, khách quan nhất dưới cái nhìn của các chuyên gia đầu tư tài chính.

Từ đó giúp bạn có thể đưa ra quyết định chọn sàn giao dịch đúng đắn.

Trang chủ: https://topforexvn.com/

Report comment