A new meta-analysis of observational studies, including 1.45 million subjects, has found that antidepressants are still linked to increased suicidality. Although this was largely driven by findings from non-SSRI antidepressants like venlafaxine, bupropion, and mirtazapine, the researchers found that publication bias and studies with a financial conflict of interest (fCOI) also likely contribute to underestimation of the risk—and SSRI studies are especially prone to these biases.

“Exposure to new-generation antidepressants is associated with higher suicide risk in adult routine-care patients with depression and other treatment indications. Publication bias and fCOI likely contribute to systematic underestimation of risk in the published literature,” they write.

The study was conducted by Michael Hengartner, Simone Amendola, Jakob Kaminski, Simone Kindler, Tom Bschor, and Martin Plöderl and published in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.

Those in favor of antidepressant use suggest that one of their primary functions is to protect against suicide. If the drugs could save lives, that would be a substantial argument in their favor. However, the evidence is, at best, unclear. Studies have found inconsistent results, with many suggesting that the drugs actually increase suicidality, especially in children and young adults. However, some studies have found unclear results, suggesting that the drugs may not increase or decrease suicidality.

In another recent study, Simone Amendola, Martin Plöderl, and Michael Hengartner analyzed the long-term suicide rates in multiple countries. They found that changes in the suicide rate did not correspond to times when large populations began using antidepressants.

However, most of these studies were limited by being randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which often deliberately exclude people who already experience suicidality and people with other comorbid conditions such as substance use. Thus, some researchers argue that these studies don’t accurately represent the patients actually seen in real-life practice.

Because of this, observational studies may provide better evidence about whether antidepressants reduce—or increase—suicide risk in real life. Studies of this type are large and include people seen in actual clinical practice, making them important for testing the validity of findings from RCTs.

According to Hengartner et al., the last meta-analysis that included observational studies was published in 2009, included only eight studies with about 200,000 participants, and did not include non-SSRI antidepressants like venlafaxine, bupropion, and mirtazapine. That study was also unable to control for publication bias and the bias of studies funded by the pharmaceutical industry (fCOI).

That 2009 study concluded that the risk of suicide was nearly doubled in adolescents taking SSRIs but that the drugs do reduce suicide risk in adults. However, that study was limited by smaller size, not controlling for biases, and not including all the drugs that are considered antidepressants.

Hengartner et al. have now updated that study, including 27 studies with 1.45 million participants, including non-SSRI antidepressants and antidepressants being used for indications other than depression, and controlling for biases like selective publication and studies sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry.

They found that antidepressants were associated with increased suicide risk in adults as well as adolescents. Moreover, even considering SSRIs alone did not reduce suicide risk—at best, suicide risk stayed the same.

“Contrary to prominent claims, we find no reliable evidence that antidepressants protect against suicide. Instead, it appears that antidepressant use may even increase suicide risk.”

Hengartner et al. were also able to assess the effect of publication bias and fCOI on the results. When they controlled for these biases, the results were even stronger, and even SSRIs were significantly associated with increased suicidality. Studies funded by the pharmaceutical industry were far more likely to find lower suicide rates than studies performed by independent researchers. Studies that make antidepressants look poor are far less likely to be published.

They write, “We further found empirical evidence for publication bias. Several studies with evidence of higher suicide risk with new-generation antidepressants likely remain unpublished. Accordingly, we found that studies with fCOI report significantly lower risk estimates than studies without fCOI.”

One easy-to-spot piece of evidence for this effect is that, on average, studies funded by the pharmaceutical industry found that antidepressants had no impact on suicide risk at all (risk ratio 0.96). In contrast, studies performed by independent researchers found that antidepressants doubled suicide risk (risk ratio 2.02).

In sum, they write that their results verify the substantial body of research finding that antidepressants increase suicidality:

“Our results are therefore consistent with several analyses of FDA safety summaries for acute depression trials that revealed an increased suicide risk with new-generation antidepressants as a group relative to placebo. A significantly increased risk of suicidal events was also meta-analytically demonstrated with SSRI in general and specifically with paroxetine in placebo-controlled short-term trials. Our results also correspond with two meta-analyses of long-term depression trials, which found increased suicide risk with any antidepressant.”

****

Hengartner, M. P., Amendola, S., Kaminski, J. A., Kindler, S., Bschor, T., & Plöderl, M. (2021). Suicide risk with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and other new-generation antidepressants in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Epidemiol Community Health, Epub ahead of print doi:10.1136/jech-2020-214611 (Link)

Duplicate comment.

Report comment

This comes as no surprise as tame company-inspired shrinks aren’t going to inquire about much of anything beyond the company backed “symptom questionnaire” in their initial interviews, which means they won’t catch perceptual distortions that should influence proper treatments- and are also a contraindication for antidepressant prescribing.

Report comment

It would take nerves of steel to drug people and children knowing you are doing harm.

There were a lot of reasons for doctors to think shrinks were a joke and that they were

screwed up.

Doctors still think this, but they are now using shrinks for their benefit.

Always getting used.

“boy I will show them. I will get respect, even if I harm people, dammit, I will be recognized

for being somebody”

Report comment

From this morning’s Courier-Journal – “The Courier Journal is tracking each fatal incident to better understand violence in the city and memorialize the victims….This list is preliminary, and the number of homicides can change as authorities investigate the circumstances of each case, determining whether the slaying was criminal, justified, accidental or suicide. The Courier Journal has excluded cases deemed accidents, suicides, fatal overdoses or hit-and-run deaths.”

If one is trying to show the linkages to the public, the readers of various news services, then why do we shy away from the source of the violence, to shy away from the causalities by which suicides can happen? To ignore and not discuss how and why a regard for the health across the community is important shows cracks in the analytics in the daily reporting?

How to address the issues? If one carves out the numbers and or the nature of aggregating data? Does the data become meaningless? Or monetized to ignorance?

Report comment

You would think that if psychiatrists really wanted to help anyone that they would want to know this sort of information. Of course, if they knew this, what would they do when someone shows up in the office who is suicidal?

Report comment

“If we don’t poison people what will we do with mentally ill(defective) people?”- Common response from psych supporters when it is pointed out that according to the science psych does nothing but harm people.

Report comment

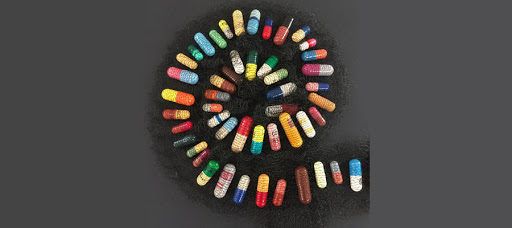

How and then why was the fibonacci spiral chosen to reflect a rotation to the left , that is counter clockwise in the manner of the pills being laid out?

Report comment

Another (possibly) avoidable tragedy: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/aug/11/i-dont-intend-to-let-my-son-down-twice-the-bereaved-father-trying-to-end-suicide

Report comment