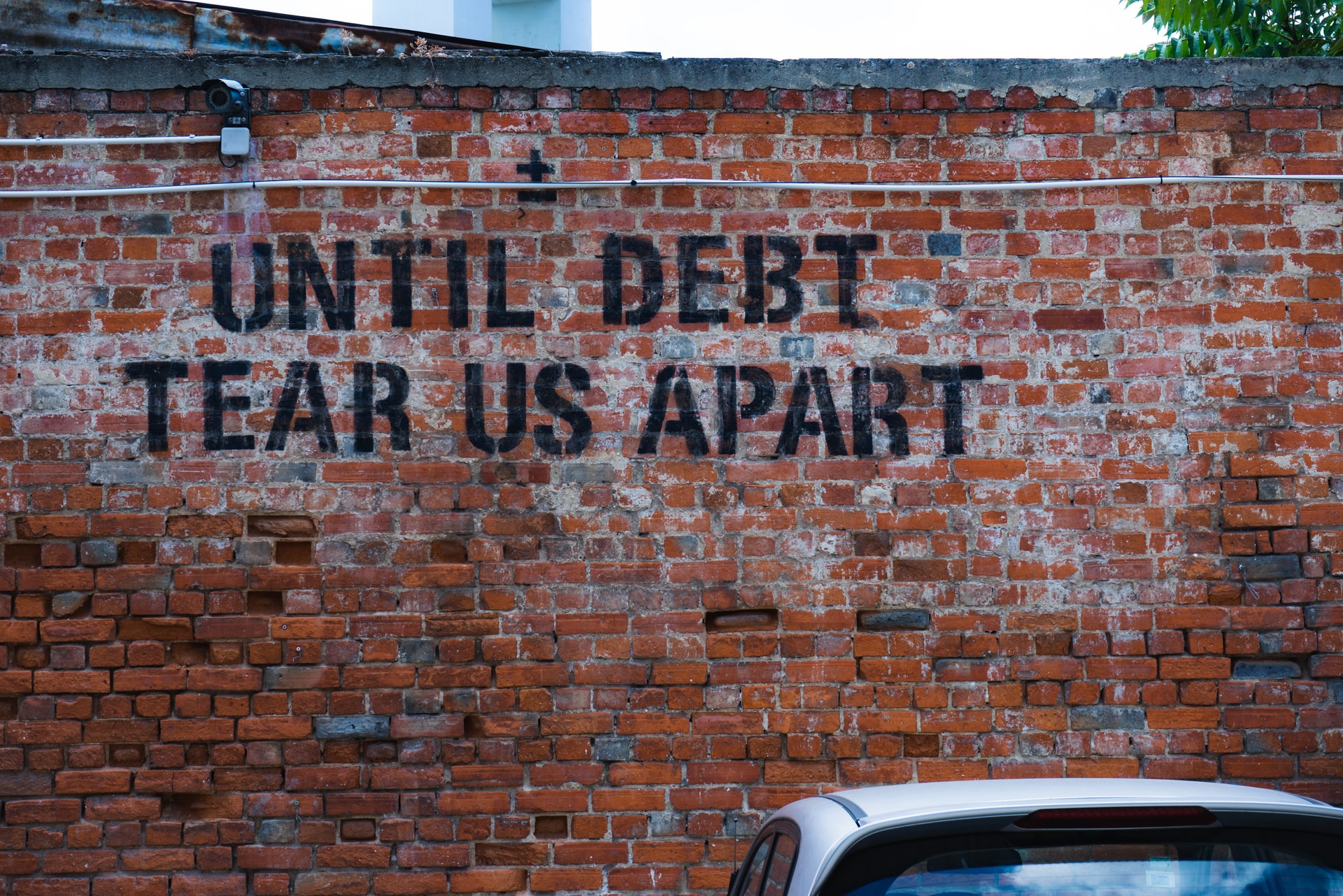

A recent editorial published in The Journal of the American Medical Association highlights new research on medical debt as a significant social determinant of health. The authors, epidemiologist Carlos Mendes de Leon and doctor of internal medicine Jennifer Griggs, discuss medical debt—often resulting from “rising health care prices and increased cost sharing in the context of no or inadequate health insurance”—in terms of “substantial adverse health effects” as well as significant financial and economic consequences.

“The profound influence of social determinants of health (the conditions in which people are born, learn, play, work, and age) has become widely recognized and accepted. Recent work on health-related social determinants and risk factors has focused mostly on factors such as poverty and income insecurity, housing and employment instability, and structural racism and other forms of discrimination,” write de Leon and Griggs.

They add, “For example, important studies in this area have convincingly demonstrated enormous health and health care inequities for people in the lowest income brackets, for people experiencing homelessness and housing instability, and for those who have inadequate employment and wages.”

Amidst calls from the UN to recognize the impact of “social determinants of health” on mental health, including recent research showing that these factors are rarely considered in clinical cases, there has been a flurry of new research examining how these social and economic forces impact individuals’ health.

One underexplored factor among social determinants of health is medical debt, accrued by individuals with either no healthcare or inadequate healthcare. The current editorial highlights recent research by economist Raymond Kluender and colleagues on the adverse effects associated with medical debt.

Kluender and colleagues’ research tracked medical debt according to two indicators: “the stock of debt (defined as the total amount of all unpaid medical debt) and the flow of medical debt (defined as the debt that appears on individuals’ credit reports during the last 12 months.”

The data analyzed were based on a random 10% U.S. sample covering 2009-2020 for credit reports sent to TransUnion, a credit report bureau.

The authors state that after 2014, medical debt overtook all other forms of debt in the U.S. They estimate that the current total amount of medical debt among the U.S. population could be as high as $140 billion.

Medical debt tends to be highest in southern states and lowest in the Northeast. The authors note that, “unsurprisingly,” the highest amounts of medical debt tend to be associated with zip codes where people have the “lowest average income levels.”

Also unsurprisingly, in states that expanded Medicaid in 2014 under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), medical debt declined significantly:

“The decline of medical debt in states that expanded Medicaid in 2014 was 34.0 percentage points greater (from $330 to $175) relative to the decline in states that did not expand Medicaid (from $613 to $550), whereas the decline in states that expanded Medicaid after 2014 was 20.4 percentage points greater (from $401 to $288) relative to the decline in states that did not expand Medicaid.”

In terms of adverse health effects, the authors explain that medical debt can “compromise seeking or receiving appropriate medical care” which often leads to either delayed diagnosis of health problems or exacerbation of preexisting conditions. This is also linked with premature mortality.

For mental health, there is a great deal of evidence for the relationship between personal debt/financial hardship and poor mental health. For instance, a recent study found that debt caused worsening mental health. Additionally, simply giving people money has been found to be a more effective mental health strategy than “treatment” in some studies.

Medical debt can lead to difficult financial and economic outcomes as well:

“Personal debt, of which medical debt is now the largest contributor, may force individuals into a spiral of economic disadvantage, including a lack of stability and security in personal life, housing and work, and social stigma. Furthermore, this pattern of economic disadvantage and lack of stability and security in essential life domains tends to cluster in families and communities and to crossover to subsequent generations.”

Explaining the “spiral” effect, the authors state that as opposed to “secured debt” such as mortgages or an automobile loan, which can result in building wealth, personal debt like medical debt often decreases wealth and “limits access to credit.”

Turning to policy, the authors argue that “the problem of medical debt in the US health care system must be a high priority.” They reiterate the positive effects of the Affordable Care Act as well as Medicaid expansion as two options here. There are problems with the ACA, though, as “deductibles, rising out-of-pocket expenses, and inadequate coverage” still plague many individuals and families.

According to the authors, “Nonetheless, the findings reported by Kluender et al suggest that effective health care policies could lead to substantial reductions in overall medical debt. Further improvements will depend on sustained advocacy for universal access to affordable health care that will not saddle patients with inadequate health care or high out-of-pocket costs.”

“Medical debt and the burden it poses on families and communities serve as yet another reminder of how social determinants of health (as they manifest through the financing of the US systems of health care, education, and housing) reinforce and perpetuate inequities in health and inequities in economic promise and prosperity,” they add.

****

Mendes, L. C. F., & Griggs, J. J. (July 20, 2021). Medical debt as a social determinant of health. JAMA, 326(3), 228-229. (Link)

I’m pretty certain the fiscally irresponsible globalist banksters, who’ve seemingly set up the greed only inspired “Rockefeller” medical community, and their scientific fraud based “mental health” system, to be their “omnipotent moral busy bodies,” about whom C. S. Lewis forewarned us against. Whose goal is to attack and steal from all the younger generations of the US. It strikes me that they are the problem.

Report comment

This subject gets really “funny” (in a soul-crushing kinda way) when you have unpayable medical debt from a suicide attempt, and it’s one of the few things that can still make you suicidal. Especially if economic factors were a big part of why you attempted in the first place.

Report comment

I chatted with a doctor once who wasn’t too happy with his own work experience, who related the usefullness of the UK NHS to me.

He said within private Medicine the Hotel Experience might be great, but the overall medical service wasn’t likely to be as good as the NHS Model.

He said Private Medicine is a business – so what would you expect?

Report comment