While suicide hotlines, such as the new national hotline 988, urge a suicidal person to “reach out” and “get help,” MIA’s Suicide Hotline Transparency Project Survey found that many struggling with suicidal thoughts fear calling hotlines because it may lead to a non-consensual intervention—a risk that can prompt a suicidal person to avoid “reaching out” for help all together.

With the recent release of 988, and the increasing marketing campaigns spread across all media, suicidality and suicide hotlines are becoming a regular presence in the daily lives of Americans. While the advent of the 988 number is heralded in the mainstream media as a positive development, there are several aspects of suicide hotlines that concern many activists, psychiatric survivors, and marginalized communities and are a source of much controversy: What are suicide hotlines’ relationships with police? And how does police intervention affect those experiencing suicidal distress?

As part of Mad in America’s Suicide Hotline Transparency Project, MIA sought to learn how suicide hotline callers felt about hotlines’ policies on police intervention and confidentiality. The MIA survey, which was conducted throughout 2022, continues to be open to anyone who has used a suicide hotline in America within the last year.

Click here to fill out this survey.

Currently, 43 hotline users have responded to this survey. Below is a review of the responses we have received regarding the impact of suicide hotline intervention policies and general lack of transparency around call tracing and confidentiality.

Fear of Non-Consensual Police Interventions

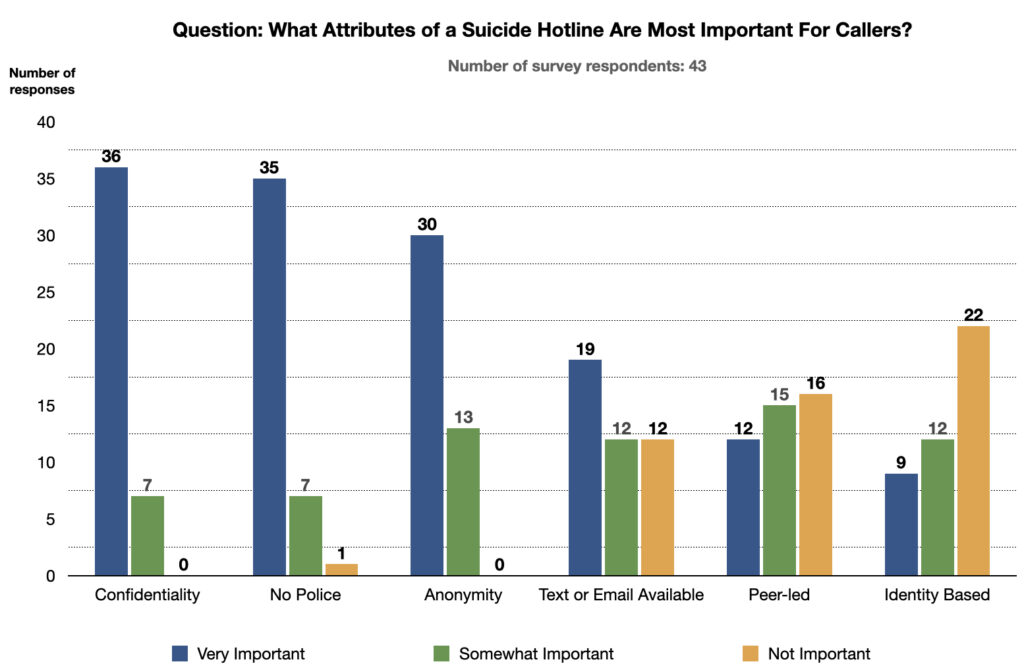

Many respondents noted that fear of police response and call tracing was present in their thoughts before calling suicide hotlines. When asked what attributes of a hotline they considered when choosing which hotline to use, “no police response” was the second most highly ranked attribute, with all but one respondent marking this as “somewhat” or “very important.”

The most highly ranked attribute was confidentiality, and the third highest was anonymity.

While the survey respondents hoped not to be met with police, they understood that this was a very real risk when calling many hotlines. When asked about the risks, fear of police intervention/violence was the top-named risk, with 20 of 43 respondents listing it. Responses outlined how a call that triggered a police intervention could have a profound impact on their lives, including loss of employment, expulsion from school, policy brutality, sexual violence, being outed to neighbors, the initiation of unwanted contact with abusive family members, police initiating a report of sexual abuse on behalf of a caller without their consent, and involuntary commitment to a psychiatric hospital.

Harm Done: Non-Consensual Interventions

Several respondents shared their experiences with non-consensual active rescue, all of them noting how unhelpful they found the experience. “They sent police over to my workplace,” one wrote. “I was so humiliated. All I was looking for was some support in the moment. I ended up being kicked out of school over the whole ordeal. It was horrible.”

Non-consensual interventions often lead to forced psychiatric treatment, and this is a risk that may provoke considerable fear among “survivors” of past psychiatric treatment. Ten of the 43 respondents stated that they feared forced psychiatric treatment, and three more mentioned a general fear of non-consensual intervention. Those expressing this fear described forced treatment as a type of incarceration, using such words as “capture,” “locked up,” and “trapped.” They described forced treatment as a distressing, traumatic experience that escalated their suicidality rather than abated it, and potentially bankrupting them with medical bills for this unwanted “treatment.”

As one respondent wrote: “I fear that the police will show up to my house, that I’ll be involuntarily committed which will cause greater psychological distress and potential long lasting trauma.”

These responses speak to how call tracing that leads to police intervention may undercut the “help” that hotlines claim to provide.

Creating More Distrust: Family, Friends and Other Resources

For most callers (32/43 responses), their hope was simple in contacting a hotline:

To be met with an understanding, judgment-free ear that would help them feel less alone.

In the survey, respondents wrote about hoping that the call would help them feel safe and understood. However, with call tracing and non-consensual intervention, many respondents told of calls to hotlines that left them feeling fearful, unsafe, and distrustful. Some respondents told of feeling betrayed when police or crisis workers were sent to their house despite explicit requests for this not to occur.

The survey revealed that many callers, having confronted this betrayal when calling a hotline, turn more distrustful toward friends, family, and even other resources that promised non-carceral response. One respondent noted that their distrust in all hotlines was so strong that they would never again call any hotline, even one like the Trans Lifeline which does not send unwanted interventions. The potential deception present in other hotlines may poison the use of all hotlines, even those that are truly confidential, as callers may mistrust even a so-called “safe” resource.

“There’s always a risk,” one respondent wrote. “Hotline counselor, warm line counselor, non-coercive warm line counselor going rogue, family, friends, professionals such as doctors or therapists that have professional liability (even if they know you well or for years). Always, always, always no matter who you talk to, except for your pet dog or cat or a select few non-coercive peer warmlines.”

Even for respondents who had never had such intervention when calling a hotline, the thought that it could occur prevented them from feeling truly safe when making a call. “I don’t feel totally safe with any U.S.-based mental health service because I know if I say the wrong thing, I could be involuntarily committed to a psychiatric ward,” one respondent wrote. Another respondent wrote, “Never call these hotlines. It is not a safe option!”

Multiple respondents who had experienced a “non-consensual rescue” said they were more hesitant to talk to anyone, including friends and family, about their suicidal thoughts, for fear of it provoking another non-consensual rescue, reoccurring trauma, and further harm.

Lack of Transparency: Policies

With the worry of non-consensual and harmful interventions uppermost in callers’ minds, many respondents told of how the lack of transparency of a hotline’s policies and definitions may further these fears. They never know if a hotline is being truthful. Several respondents told of being deceived by hotlines that lied about their policies and gave “nonsense lip service” about anonymity and confidentiality.

One respondent wrote: “I wasn’t sure if there was something I might say that would trigger the hotline staff to contact police. They didn’t provide [me with] information on how they make that judgment call.”

Even when hotlines do disclose their policies around confidentiality and call tracing, they often use vague language to define terms that, according to our survey, are misunderstood by the public.

Lack of Transparency: Terms and Definitions

In many cases, the lack of transparent and accessible definitions of terms can be the difference between a caller knowing how to keep themselves safe and encountering unwanted, traumatizing, or lethal intervention. We asked respondents to guess the definitions of some common words used by hotlines, including “confidential and anonymous,” “nonconsensual active rescue,” and “only in extreme circumstances.” The responses revealed that callers often have little idea what such phrases mean in the context of a call to a hotline.

Confidential and Anonymous:

Twenty-two out of 43 respondents perceived this phrase to prohibit the sharing of their personal data with others outside the crisis line; 19 respondents thought it meant that the hotline was unable or unwilling to identify or trace the caller; and 4 believed this phrase to mean no police involvement.

Five respondents indicated that there were exceptions to the promise of confidentiality and anonymity, though they were unsure what those exceptions are.

Extreme Circumstances:

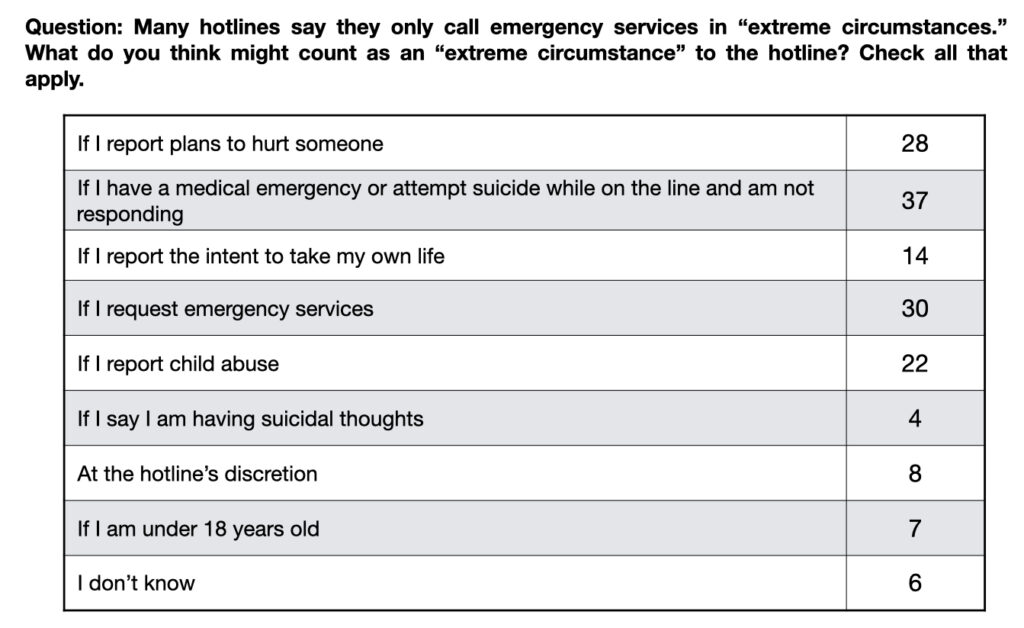

Hotlines often use vague language such as that they only send police “in extreme circumstances.” We asked respondents (in a multiple choice question) what they believed constituted an “extreme circumstance” from the hotline’s point of view. There were nearly as many different combinations of responses as there were respondents.

Respondents stated that they believe the “extreme circumstance” exception is unevenly and discriminatorily applied, that in fact it can “happen to any caller,” and that hotlines “will always use their ‘discretion’ to rationalize getting the cops involved whether it’s right or not.”

One respondent wrote: “I as a very experienced service user, have complete and total ignorance on what might or might not trigger an authority crisis response. Like, absolute zero knowledge. In over 8+ years of engagement with literally dozens of mental health services at every stage of the service chain, this information has never been freely or directly offered.”

Because of this fear of nonconsensual active rescue, and distrust of hotlines policies and practices regarding such interventions, many respondents stated that they couldn’t be honest when calling hotlines (and other resources) that exist to provide support to people in distress. Respondents wrote that they feared giving the “wrong answers” and had to lie. Some even told of how they felt, on a call, they had to ease the distress of the person who had answered their call.

As one respondent wrote: “I had to adjust my dialogue and convince them I would be ok. More effort than help.” Another said: “It felt more about their comfort versus mine.” Those who had called hotlines multiple times told of how they had learned “how the game works” and developed a script to “get help without saying the wrong things.”

Hotline Operator Behavior

The survey revealed yet another frequent shortcoming of hotlines: those staffing the call may seem to be focusing on completing a risk assessment rather than just listening. Respondents told of how the conversation often felt robotic, scripted, and cold, or that operators were just “funneling them off.”

“A major part of the crisis structure is to guide you in a ‘hand-off’ to the next resource,” one respondent wrote. “When no ‘next resource’ exists, crisis workers seem woefully ill-equipped and disempowered to help. There is no answer to that situation, and that’s a problem.”

For callers who want nothing more than just a kind ear, this can feel really invalidating. Another wrote: “I could sense the listener was busy typing and writing, and I could hear that. I just wanted them to focus, BE present.”

While the respondents told of many criticisms of hotlines, they also told of how, despite their many criticisms, they still dialed for help in moments of great distress because, as several said, they had no other options. As one respondent wrote: “Regardless of what I think of [the hotline’s confidentiality policies], does it matter? If the crisis line is my ONLY resource, I don’t have the luxury of thoughtfully considering any ramifications of confidentiality.”

Thinking About Solutions

One respondent to the MIA survey wrote: “It feels absolutely dreadful being a passive user of these services with no say in how they are delivered or what could or should change.”

As the 988 national hotline is rolled out, the MIA survey responses show a way forward that could help to dispel the criticisms arising around suicide hotline policies. Hotline providers could conduct in-depth surveys of hotline callers, asking them what they found helpful and what they found harmful, and rely on their feedback—particularly around non-consensual interventions—to amend their practices.

When we asked callers if they felt safe with the support they received from the hotline, six reported that they did feel safe. Five of the six said this was because they were confident that their call was confidential and would not be traced. Three of the six said that being honestly informed about what would trigger a non-consensual intervention helped them feel safe. Many respondents said that even when they knew that a hotline practiced non-consensual active rescue, that if the operator was open, honest, and forthcoming about when and how these types of interventions could occur, that this contributed to an increased feeling of safety.

A Way Forward

What the respondents of the MIA survey stated about protocols that would make hotline callers feel safe is clear:

- Avoiding call tracing and police response is the easiest way to make a hotline feel safe and approachable for people calling.

- Create and fund more hotlines that refrain from non-consensual practices.

- For hotlines that do practice non-consensual active rescue, they should offer accessible, clear, and truthful definitions of terms.

- Transparency and clarity around all hotline intervention policies are essential to providing help and creating a trusting relationship with any caller.

Trans Lifeline Advocacy Efforts

The results of the MIA Suicide Hotline Transparency Project Survey were handed over to the the Trans Lifeline’s Safe Hotlines Project to be used in a study on the pipeline between crisis hotlines, “corrections” and involuntary “treatment”. Their research team is made up of scholars from several academic institutions who are seeking to demonstrate:

- The scope of the issue and the harm done to those most impacted.

- Outline the privacy concerns inherent to non-consensual intervention.

- Center survivor experiences with involuntary emergency responder intervention on crisis calls.

- Provide recommendations for alternatives and harm reduction based on interviews with these survivors.

- A roster of emails of crisis centers.

- A review of response (rate and contents) to MIA questionnaires to improve survey questions and increase response rate.

- Cross verification for an updated list of affiliate crisis centers since the 988 website indicates as of today more than 200 affiliates.

You can learn more about the Safe Hotline project at Trans Lifeline here.

This survey continues to accept responses. If you would like to fill out the survey, please click here.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gVBNRCorPXk

“Fail to get an answer, Satan’s crossed the wire.

By some strong delusion, or some hearts desire,

Take away obstruction, God is on the throne,

then you get your answer through the Royal Telephone.”

I’d really like to put this piece of music to the video of Police stomping the head of a ‘mental patient’ who sought ‘help’.

Seems that Satan might have been given a warrant to ‘listen in’ on the ‘confessional’.

The release of your ‘personal and confidential’ information won’t be immediately apparent to you, but it will when the ‘poison’ starts to take effect. Oldest trick in the Book? Adams apple, the exploitation of trust by a snake. My most personal and traumatic experiences told to a social worker (in good faith) included in the “edited” documents released to the public after I made a legitimate complaint about serious misconduct by a hospital.

Anything you tell these people will come back to haunt you should they ever feel a need to ‘coerce’ you into ‘consenting’ to whatever it is they wish. The ‘laws’ protecting your confidentiality are never used to prosecute anyone who does release your information. “Trust in haste, regret at leisure”.

Report comment

Thanks for this article, both of you. I share many of the same reservations about the new & improved 988 line. I did participate in a Zoom meeting with (possibly?) some government employees or mental health advocates on this subject. They were in Mass. (I believe) & claimed that geolocation tracking would not be employed. I’m not sure if I believe them.

Report comment

Hotlines are of very little use. You have to be extremely careful what you say to them.

If you really do want non-consensual intervention, then best just go down to the police station and tell it to the desk sergeant. Bring your tooth brush.

Joshua

Report comment

Sad but true. Going to them also avoids the problem of neighbors seeing authorities showing up (in my case it was a whole parade of emergency vehicles, with lights flashing) to your residence to take you away. I’ve lost housing more than once because of this.

Report comment

I was hospitalized twice, voluntarily, but would never call a hotline for fear of being sent back. Those hospitalizations gave me PTSD on top of my other mental health challenges, which has made dealing with them even harder subsequently.

Report comment

You are far from alone. I used to work at a crisis line (a volunteer-based one), and people would report calling us because they knew they couldn’t talk to their therapist or else they’d be sent to the “hospital.” This was especially true for people who cut on themselves and were not in any way suicidal. We never would send out police on those calls, but we did sometimes trace suicidal calls on those who appeared to be about to act on a plan to kill themselves. I know that this and other hotlines have been “professionalized” (no longer volunteer based) and are much more likely to send the police on callers than we were. I volunteered for a hotline here in Olympia, WA, who did not ever trace or dispatch on anyone unless they asked us to do so. But such hotlines seem to be disappearing. I also have known many who found being hospitalized so traumatizing that they’d rather suffer their “symptoms” forever rather than risk being sent there. It is a sad commentary on the level of “help” that is currently available.

Report comment

I’m interested in the cost benefit analysis that says this is a good use of scarce resources. On the surface it sounds like a great idea but does it actually help people? My medical provider is currently hiring for this hotline and as someone a BA in psychology and way to much personal experience it is a tempting employment solution to my Medicaid problem.

Report comment

My guess would be that it depends on the person/people you get to talk to, as well as the general philosophy of the hotline. The more “professionally staffed” the hotline is, the less likely I think it would be helpful.

Report comment