Involuntary commitment in psychiatry is typically justified by the argument that it is necessary to keep people from harming themselves or others. However, the results of a new study out of Norway published in BMC Psychiatry in February 2023 undermine this assumption.

The Norwegian authors Olav Nyttingnes, Jūratė Šaltytė Benth, Tore Hofstad, and Jorun Rugkåsa write:

“The assumption that involuntary care protects patients from negative outcomes is not supported by our findings, but neither can it be ruled out…this raises the concern that involuntary care may not work entirely as intended by lawmakers and clinicians. This might be because predicting suicides and other rare events are notoriously difficult. We know that previously committed patients have a greater likelihood of later involuntary care, which may maintain the patterns of involuntary care without fully taking into account the patient’s symptoms or risks.”

“Given the concerns voiced by user organizations, the ethical concern surrounding the provision of treatment without a person’s consent, and over geographical variations in such treatment, there is an urgent need for additional studies that test core assumptions of mental health acts.”

The study began as an attempt to fill the gap in the available literature concerning the efficacy of involuntary commitment. The authors noticed that although involuntary commitment practices are utilized worldwide and are frequently codified into law through national mental healthcare legislation, in their case, the Norwegian Mental Health Act, there is little to no research demonstrating that low rates of involuntary commitment there were higher rates of harm.

The study began as an attempt to fill the gap in the available literature concerning the efficacy of involuntary commitment. The authors noticed that although involuntary commitment practices are utilized worldwide and are frequently codified into law through national mental healthcare legislation, in their case, the Norwegian Mental Health Act, there is little to no research demonstrating that low rates of involuntary commitment there were higher rates of harm.

Given the lack of research, the authors designed a research plan with five specific research questions:

- Do patients with SMDs [severe mental disorders] who live in areas with a lower level of involuntary care have increased case fatality compared to those with higher levels?

- Do patients with SMDs who receive only voluntary care in the index year and live in areas with lower levels of involuntary care have higher use of inpatient care in the two subsequent years compared to those with higher levels?

- Do patients with SMDs who receive only voluntary care in the index period and live in areas with lower levels of involuntary care experience shorter times until an episode of involuntary care?

- Does the number of patients with an SMD diagnosis increase over time in areas with lower levels of involuntary care?

- Is the number of suicides per population higher in areas with lower levels of involuntary care compared to areas with higher levels?

They hypothesized that the areas in Norway that report low rates of involuntary commitment would, in turn, report higher rates of inpatient care use, diagnosis of disorders, recidivism rates, suicidality, morbidity, and mortality. In comparison, areas with increased rates of involuntary commitment would report lower rates of inpatient care use, diagnosis of disorders, recidivism rates, suicidality, morbidity, and mortality. They call the rate of involuntary commitment and its following outcome an “involuntary care ratio.”

Using the national Norwegian Patient Registry from 2014-2018, the authors conducted a retrospective study where the involuntary care ratio in the area a patient lives is studied as a predictor of subsequent outcomes. The ages of the population studied ranged from 18 to 65 years old. Similarly, they collected data on completed suicides from the Norwegian Cause of Death Registry.

After collecting the raw data, the authors operationalized the data by identifying and defining six different variables that contributed to their data analysis.

The six variables were:

- Severe mental disorder (SMD) – given that the Norwegian Mental Health Act discourages involuntary commitment for mental health disorders that do not meet specific standards of psychosis, the authors defined SMD as a diagnosis on the schizophrenia spectrum or bipolar disorder with psychosis.

- Involuntary commitment – was defined as an involuntary inpatient or outpatient care or observation sanctioned by the Norwegian Mental Health Act.

- Mental health inpatient days – the combined number of days the patient was in the hospital for the calendar year.

- Area of residence – The local authority nearest to the patient’s address.

- Urbanicity — was classified as one of five levels of urbanicity, with 1 being densely populated major cities to 5 being sparsely populated areas.

- Area deprivation measures unemployment, poverty, literacy, and mortality.

Utilizing the above variables, the authors created their primary covariate, the standardized involuntary care area ratio (SIAR). This independent variable was designed to measure the level of involuntary commitment and care in an area in relation to hospital/inpatient recidivism, suicidality, morbidity, and mortality. For example, if an area had a low SAIR, it had lower rates of involuntary commitment and vice versa.

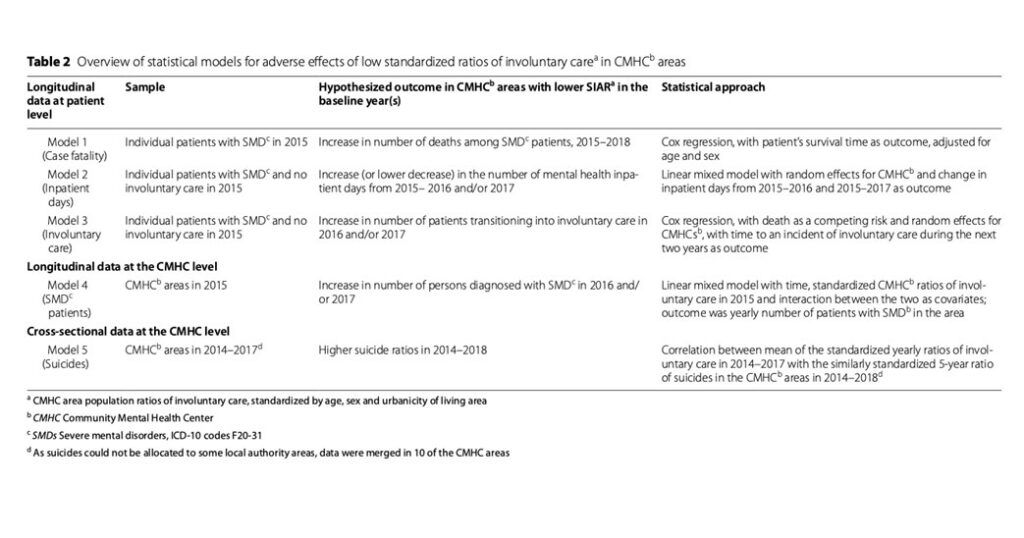

The authors then predefined five models to answer their research questions concerning the effects and efficacy of involuntary commitment.

In Model 1, SIAR had no significant effect on case fatality.

In Model 1, SIAR had no significant effect on case fatality.

In Model 2, they investigated the change in mental-health inpatient days for voluntary SMD patients dependent on SIAR. The model showed non-significant interactions, indicating no overall differences in the association between SIAR and the change in inpatient days.

Model 3, which investigated involuntary psychiatric hospital recidivism, showed that SIAR did not predict higher rates of return to psychiatric hospitals via involuntary commitment.

In Model 4, which sought to understand whether or not more people in places with lower SIAR were diagnosed with SMDs, there was a lower rate of individuals diagnosed with SMD in places with less involuntary care.

Lastly, Model 5, which compared suicide rates, found a non-linear relationship between SIAR and suicide rates.

The authors write:

“Using a continuous, standardized measure of each area’s level of involuntary care (SIAR), we tested five models of possible adverse effects of lower use of involuntary care and found no statistically significant effect for patients with an SMD. We did not observe significantly more case fatalities, deterioration into involuntary care, or increases in inpatient days for patients with SMDs, nor did we find increased rates of SMDs or notable increases in the numbers of suicides at the area level. In addition to investigating linear effects, we checked all outcomes for non-linear relationships to identify potential cut-off values for high vs. low SIARs with differential effects on outcomes but found none. Overall, our findings did not support the hypothesis that areas with low standardized rates of involuntary care place patients with SMD at higher risk.”

The primary limitation of this research that the authors note is that it is an observational study. They encourage further research to examine, in greater detail, whether or not mental healthcare legislation protects life and rights in the ways intended by its core assumptions, which at times can be inherently paternalistic.

Indeed, it is well documented that involuntary care frequently does more harm than good for psychosocially disabled and mad people.

****

Nyttingnes, O., Benth, J. Š., Hofstad, T., & Rugkåsa, J. (2023). The relationship between area levels of involuntary psychiatric care and patient outcomes: a longitudinal national register study from Norway. BMC psychiatry, 23(1), 112. (Link)

Another study that should start its conclusion with

“To absolutely no surprise to anyone with lived experience…”

Report comment

“Well, but, you see, it’s because the people in areas with high commitment rates are SICKER, that’s WHY they have higher commitment rates, I mean obviously, it’s not OUR fault, and it CERTAINLY doesn’t mean that commitment isn’t REALLY IMPORTANT as a tool in… oh, fuck, let’s just pretend we didn’t read that…”

Report comment

Too easy to become cynical when every profession uses a different language. How to convey the “organizational mind” that favors innovation, learning to learn, and a better way forward (though do we need to understand our personal and collective history, too?) Have your explored any of Zygmaunt Bauman’s writings?

Report comment

I have not. Do you have a suggestion?

Report comment

The one that prompted me to respond to this post was:2008: Does Ethics Have a Chance in a World of Consumers? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02780-9

another: 2004: Wasted Lives. Modernity and its Outcasts. Cambridge: Polity. ISBN 0-7456-3164-9

To realize the presence of a better ethical context in the decision making process within the individual and collective self in the rate of change contributes to a certain structural upheaval. Hope these are of interest, but do explore his Bibliography.

Report comment

Sounds like my kind of book!

Report comment

“Overall, our findings did not support the hypothesis that areas with low standardized rates of involuntary care place patients with SMD at higher risk.”

“Indeed, it is well documented that involuntary care frequently does more harm than good for psychosocially disabled and mad people” … and everyone else, too!

And since forced psychiatric maltreatment also causes people to avoid all medical care, as much as possible in the future, which is bad for business for all doctors. Most definitely, forced psychiatric treatment should be made illegal.

Report comment