Mental health, a topic traditionally dominated by psychiatric and psychological theories, is undergoing a profound evolution. A recent study highlights the increased richness and diversity of mental health models that are being used to frame our understanding of the mind, madness, and emotional suffering.

Researchers Dirk Richter from Bern University of Applied Sciences and Jeremy Dixon from the University of Bath published a quasi-systematic review of theoretical models of mental health problems in the Journal of Mental Health. Their work highlights the diverse landscape of models and approaches that have sought to understand, describe, and analyze mental health issues.

The traditional dominance of psychoanalytic and social theories from the 1940s to the 1970s shifted to a biomedical paradigm in the 1980s and 1990s. But as the 21st century progresses, challenges to singular perspectives have multiplied.

“Contemporary arguments about the nature of mental health problems have tended to focus on the tension between polar positions, i.e., biomedicine or the critical perspectives proposed by the user/survivor/critical psychiatry camps. While the bio-psycho-social model has been used to hold divergent perspectives together, this consensus seems to be fracturing,” Richter and Dixon note.

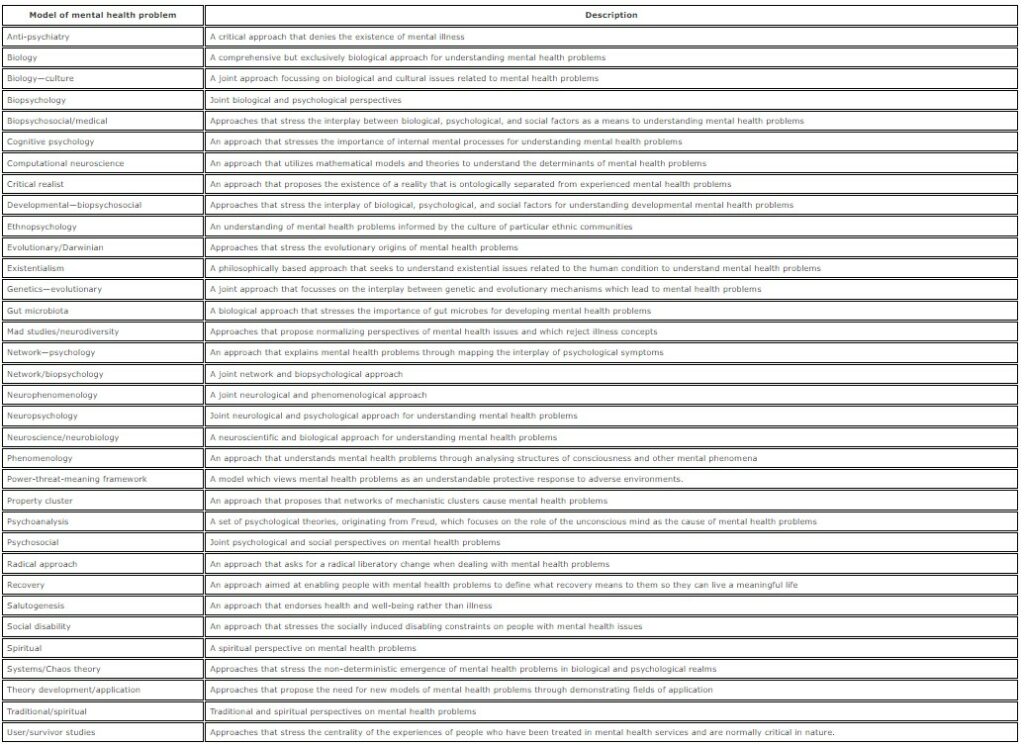

Drawing from a wealth of resources, from academic articles to books, this new study identified 34 distinct models of mental health problems. These were categorized into five broader groups: biological, psychological, social, consumer, and cultural.

Mental health and mental illness have been subjects of contention across various fields, from medicine to sociology, for many years. From the 1940s to the 1970s, the discourse was dominated by psychoanalytic and social theories. However, the 1980s and 1990s saw a shift towards biomedical models, peaking in the 1990s when it was named the “Decade of the Brain” by the U.S. Congress.

As the 21st century commenced, the understanding and classification of mental health problems became more disputed, especially with the release of the fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5). Criticisms were not only external but also from within the biomedical community, leading to significant debates.

The biomedical community has been embroiled in discussions regarding dimensions versus categories of symptoms, the etiology of mental disorders, and the comorbidity of distinct disorders, among other topics. Recent network research has questioned the existence of hundreds of separate disorders, suggesting instead the presence of only a handful of overarching dimensions.

Practical questions persist, with definitions of mental health problems influencing legal and policy decisions. A compelling need has arisen for comprehensive mental health model reviews encompassing diverse perspectives, especially those of service users. The researchers’ choice of the term “mental health problems” was intentional, striving for consistency and inclusivity across varied publications.

The researchers conducted a quasi-systematic review of mental health theories and models, primarily using databases like Pubmed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO and also searching Amazon.com. The study aimed to understand the diversity of models from 2000 onwards in various languages, excluding empirical and purely philosophical works.

For methodological transparency, they registered the study with the Open Science Framework. The extensive and varied data were presented graphically, with detailed models tabulated and a list of all referenced publications provided as supplementary data.

Their research synthesized 110 out of 3423 publications, grouping them into five pivotal categories: Biology, Psychology, Social, Consumer, and Cultural.

- The Biology category primarily emphasized the brain’s role in mental health and the need for a brain-based taxonomy.

- The Psychology category housed theories like salutogenesis, cognitive psychology, psychoanalysis, network psychology, and existentialism, each proposing distinct lenses to view mental health.

- The Social category highlighted the influence of social factors on mental health, with models emphasizing socially induced constraints and the effects of real-world events.

- The Consumer category consisted of models reflecting the experiences of those treated by mental health services, emphasizing recovery, normalizing mental health concepts, and stressing the significance of patients’ experiences.

- The Cultural category addressed cultural, traditional, and spiritual interpretations of what is termed as illness in psychiatry.

Several models merged two or more primary categories, forming a spectrum of interdisciplinary approaches. For instance, biopsychology bridges biology and psychology, encompassing sub-models like network biopsychology and neuropsychology.

Psychosocial models, sitting between the psychology and social categories, focused on the interplay between individual psyche and societal factors.

Radical approaches and anti-psychiatry models, positioned between the social and consumer categories, either aimed to liberate those with mental health issues from existing paradigms or critically questioned the existence of mental illness.

Some models drew non-linearly from the five primary categories, such as ethnopsychology, which intertwines cultural and psychological insights. The study emphasizes the diversity and complexity of models and approaches in understanding mental health problems.

Richter and Dixon speculate on the increasing diversity of mental health models. The drive for specialization in science, dissatisfaction with conventional classification approaches like the DSM, and the emerging voices from non-medical professions all contribute to this growing diversity.

“We conclude that mental health care needs to acknowledge the diversity of theoretical models on mental health problems.”

Their work emphasizes the need for a more holistic and inclusive view that moves beyond the traditional psychiatric and psychological lenses.

This review offers the first comprehensive look at models of mental health problems using a systematic review methodology. By examining various sources from natural and social sciences, service users, activists, and traditional or spiritual/cultural approaches, a myriad of perspectives on the definition and etiology of mental health problems have been identified.

The research includes a vast array of models, both old and new, such as psychoanalysis and computational neuroscience. A vital takeaway is that more recent models don’t necessarily eclipse the older ones but rather augment them.

Their findings highlight the diverse goals associated with different models. For instance, while some models advocate for a purely biological or psychological understanding, others lean towards political or legal solutions.

The study underscores a pivotal shift: the definition of mental health problems should be collaborative, integrating insights not just from the medical sector but also from the communities directly impacted.

The study presents two overarching theoretical approaches: the first acknowledges the coexistence of diverse models, advocating “Epistemic Pluralism.” The second proposes an overarching meta-theory, promoting novel research methodologies, drawing from “Post-psychiatry” and “polycontexturality.”

This requires clinicians to attain “Conceptual competence,” ensuring they recognize varied foundational concepts and assumptions and don’t misinterpret them as symptoms of illness.

Moreover, a multifaceted approach can address legal and political challenges, especially regarding the rights of service users. Lastly, amplifying the voices of non-medical professionals and service users in discussions about mental health models is crucial, fostering collaborations between them and academics for a more comprehensive discourse on mental health challenges.

****

Richter, D., & Dixon, J. (2023). Models of mental health problems: a quasi-systematic review of theoretical approaches. Journal of Mental Health, 32(2), 396-406. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.2022638 (Link)

I see nothing in this article that discusses nutritional models of psychiatry, even through the obvious evidence that scurvy, pellagra and beriberi have “psychiatric” consequences. Does this mean that I get to remain a top hometown psychiatrist without going to medical school?

Report comment

As a corollary, just to provide my context of how mind-boggling with “just” experiments would be to find correct models out of 34 would be:

There are 34×33 pair models (1,122). I take any of the first 34 and then take any of the remaining 33.

There are 34x33x32 trio models (35,904).

Now, I can make or have to make a sum of (1,122)+ (35,904) + (1,113,024), etc. “models”.

But it’s not that bad!. There is just one model that includes all the 34 models. And there are only 34 or 33 models, I’m lazy, that exclude just one, i.e. it includes only 34 models. I take sequentially each of the 34 models out of the set of models and voila! 34 models, or 33?

So asuming that each model or group of 2, 3, etc., models have a SINGLE experiment that conclusively proves that model is correct that would take an astronomical amount of experiments…

The asumption of one single decisive test comes to me from how Relativity was proved correct: By a single experiment by I think two research teams measuring the displacement of the observation of stars observed near the sun during an eclipse. And that’s around 100yrs ago.

And I am agnostically guessing these models are nowhere near a single such scientifically conclusive test.

Report comment

I realized that I made mistakes when making my corollary. I was describing groups of ordered pairs, ordered trios, etc.

That is I was considering the model grouping models 1 and 14 is different from 14 and 1.

That’s my mistake. At least 🙂

But realizing my mistake, I can see that when calculating the order of implementation of the lessons or recomendations from those models I fell short…

Because out of 4 moodels: 1, 14, 28 and 34, either can be implemented first, then out of the remainder 3 another and so forth. The number of sequences of implementation seem to correspond to what I described in my corollary.

Except, two interventions can be applied together, say 14 and 28 have to be implemented together, before or after 1 and 34. And so forth.

And that’s a different grouping that compounds the already astronomical implementation problem, when order maters.

And that sounds to me not an exponential problem, but a factorial problem in mathy terms. Those kinds of problems are extremely difficult even for supercomputers to sort out.

No chance in computational heaven…

And I know I sound pedantic or beyond the point, but some implementation sequences might be detrimental and therefore in my mind have to be sorted out. Probably by a computer at some point, given the complexity, number of models and likelihood of harm if implemented in the wrong order.

When I am sure I sound pedantic is when I say that not implementing the lessons from a model is in itself an implementation, like not using SRRIs. Or not using SRRIs first, or at some point in the sequence, or at all. ;p

Report comment

Well, I think one invalid assumption of building models for mental health is that such models will describe anything for anyone.

It should not be an assumption, it should be a fact. A goal even if conceding that might not reach at all, if I follow just the trend of proposing models.

What is the proof any set of models describe reality better?

Since, aprioristically, without knowing anything specific about the 34 models, at least, since philosophical and “just” empirical models were discarded, any of them is likely to be correct less than 1 out of 34.

Which sounds odd for modern science, even invalid to me, since maybe ignoring and overgeneralizing, none of those models is a theory, in the sense of a Scientific Theory.

They are most likely not based in statements, usefull ones, beyond doubt. As at least one definition of Scientific Theory demands.

So, to me those models can’t be, by definition theoretical models in the scientific sense.

And aprioristically assuming one is correct, even if it’s the set, the grouping of the 34 individual models, then the probability for any model to be correct is 1 in 35. Including the set, the grouping of all the models. Aprioristically.

If there was a new model, say a grouping of models 1, 14 and 28, aprioristically that puts the probability of any being correct in 1 in 36. And so forth.

Assuming, of course, cheaty me, one and only one is correct. But fair assumption to me since it appears to me the reviewed research fits into the wider search for A model, even if it includes ALL of them or SOME of them…

So, aprioristically the more models are proposed the less likely is that any is correct. That also jives with common sense: The more remedies are peddled for a disease, the less likely is that they actually work. That was a well known rule of thumb in my decades ago medical circle.

And going into the specifics of each model to dilucidate if one, two or many as a group is/are correct can’t be done scientifically, since at least by their grouping, their “agnostic category”, they are not beyond doubt.

That’s empiricism, religion, philosophy or something else. Not scTience, in my hopefully humble opinion…

Report comment

This is a good review of possible models, leaving us to wonder how to proceed. From my 45 years of looking at mental health from both sides (person with lived experience and psychiatrist) I use a self determination/ trauma informed approach, based on protection of rights as beginning principles. I did not see the power, threat, meaning (PTM) model from England described. It encompasses the three elements I highlight. I believe that every person identified as having a mental health problem needs a peer advocate to amplify their voice (especially nonverbally through an approach developed by peers called emotional CPR) and have their hopes and dreams heard and taken seriously using Dialogical therapy such as Open Dialogue.

Madness is usually the result of not having a voice in one’s life decisions (ie lacking social/emotional power). Then much of our madness will dissolve as we are heard and understood. Then we can engage in society as an active participant not just a victim. Each interaction will carry the opportunity for connecting not for retraumatization.

Report comment

“Madness is usually the result of not having a voice in one’s life decisions (ie lacking social/emotional power). Then much of our madness will dissolve as we are heard and understood. Then we can engage in society as an active participant not just a victim. Each interaction will carry the opportunity for connecting not for retraumatization.”

YES!!! It boils down to being heard and understood, even if only by yourself. Academia’s endless obsession with categorizing is a complete waste of time.

Report comment

There is a glaring omission. Susan Rosenthal’s sterling work on how the economic system seriously damages human existence isn’t mentioned at all.

Report comment

A thoughtful discussion to initiate our conversation, with no cause for concern. It is important to recognize that technology is shaping the definition of mental illness as individuals increasingly engage in online discourse, expressing thoughts that were previously constrained two decades ago. In the near future, IMHO, mental illness may be confined to cases involving physical harm to oneself or others, or acts of significant violence. However, even in such instances, questions may arise regarding the individual’s mental state at the time, with the exception of the latter, which may be more straightforward and sanctioned legally.

For all other scenarios, it is likely that society will consider them as personal costs or risks, as we collectively acknowledge our responsibility and accountability for our thoughts and actions.

Diversity in mental health means to me bending or breaking the rule of psychiatry and I think that is already under great strain!

Report comment