Defenders of psychiatry, who like to tell of “evidence-based” practices, regularly describe critics of psychiatry as “biased,” or of “cherry-picking” the data, or of how such criticisms arise from those who are “antipsychiatry,” and thus are motivated by a hostility toward the profession. Mad in America is often characterized in this way, and on a personal level, I have heard such comments since I published my first book on this topic (Mad in America in 2002.)

I mention this because a recently published “Viewpoint” in JAMA Psychiatry provides an ideal way to put this criticism to the test, and elucidate what we do.

Over the past ten years, we have published reviews of numerous peer-reviewed articles that have concluded there is little evidence that schizophrenia is a “genetic” disease, and that, in fact, genetics account for very little of the “risk” for being so diagnosed. On January 20 of this year, we published an MIA Report, written by Peter Simons, our front-page editor and long-time science writer, that provided an exhaustive review of the search for the genetic causes of schizophrenia, and the title neatly summed up the bottom line: “Searching for the Psychiatric Yeti: Schizophrenia Is Not Genetic.”

However, in the February 28 online issue of JAMA Psychiatry, Kenneth Kendler—who is one of the most prominent psychiatric researchers in the world—presents an argument that genetic research provides “robust” evidence that there are “causal pathways to psychiatric illness” in the brain. He writes:

“Can we show that critical causal pathways to psychiatric illness occur in the brain? To proceed, I use the most robust empirical findings in all of psychiatry—that genetic risk factors impact causally and substantially on liability to all major psychiatric disorders. I capture this relationship in a simple causal diagram: risk genes → psychiatric disorder.”

Thus, you can see, in our MIA Report and Kendler’s piece, two discordant conclusions regarding research on the “genetics” of schizophrenia. And here is the opportunity: if we review the evidence that is present in each of these two publications, we can assess whether Mad in America readers—or JAMA Psychiatry readers—are being provided with the most robust, and up-to-date, review of the scientific literature.

The Journalistic Roots of Mad in America

As background to this question, it is important to understand the journalistic roots of Mad in America. Those roots go back nearly 25 years, back to when I published Mad in America, my first book on the subject. Knowing this history can help readers understand what we do, and why.

At that time, psychiatry was telling a story of great advances in understanding the biological causes of schizophrenia and of drug treatments for the “disease.” In Mad in America, I sought to see if that narrative of great scientific discovery was supported by the science.

The narrative of advance took flight in 1980, when the American Psychiatric Association published the third edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM III). As Nancy Andreasen declared in her 1984 book The Broken Brain, the conception present in DSM III was that “the major psychiatric illnesses are diseases. They should be considered medical illnesses just as diabetes, heart disease and cancer are. The emphasis on this model is on carefully diagnosing each specific illness from which the patients suffers, just as an internist or neurologist would.”

Soon, the public began hearing about how the different disorders were caused by specific chemical imbalances in the brain. Depression was due to low serotonin, schizophrenia to too much dopamine, and ADHD to not enough dopamine. This was a story of diagnoses that had been proven to be brain diseases—the pathology of these major disorders had been found.

In 1995, the editors of the American Journal of Psychiatry wrote that DSM diagnoses had been “validated by clinical description and epidemiological data . . . The validation of psychiatric diagnoses establishes them as real entities.”

A few years later, APA president Carolyn Rabinowitz was even more emphatic. “Mental disorders are [now] recognized as real illnesses,” she said, adding that just “as cancer is highly treatable and can be cured, we are experiencing a similar success in psychiatry.”

All of this told of great medical progress. Prozac was introduced into the market in 1988, touted as a “breakthrough medication,” and other companies soon produced me-too SSRIs. Then, in the mid-1990s, atypical antipsychotics arrived on the market, which were also heralded as “breakthrough medications.” The new drugs were touted as medicines that “fixed the chemical imbalances that cause schizophrenia, depression and other major disorders,” and thus were “like insulin for diabetes.”

Here is how the Los Angeles Times described the therapeutic advance provided by the new atypical antipsychotics: “It used to be that schizophrenics were given no hope of improving. But now, thanks to new drugs and commitment, they are moving back into society like never before.”

Given the complexity of the human brain, this was a story of arguably the greatest advance in the history of medicine. The pathology of major disorders was now known, and researchers had produced drugs that “fixed” that pathology.

That was the story I was told in 1998, when I co-wrote a series for the Boston Globe on abuses of patients in research settings. The experts I interviewed, including future American Psychiatric Association president Jeffrey Lieberman, all told me that schizophrenia was due to a dopamine hyperactivity in the brain, and that antipsychotics, by blocking dopamine transmission, helped remedy that abnormality. Again and again, I heard the refrain “like insulin for diabetes.”

When I researched Mad in America, I investigated the truth of that story in a simple way. I sought to see if the scientific literature supported it. Here was the crux of that investigation:

- Was there evidence that the introduction of antipsychotics in asylum medicine in the 1950s had led to a marked improvement in outcomes for those diagnosed with schizophrenia?

- Was there evidence that schizophrenia had been validated as a discrete disorder?

- Was there evidence that it was due to a chemical imbalance in the brain?

- Was there evidence that the atypical antipsychotics were breakthrough medications that provided a dramatic upgrade over the first-generation antipsychotics?

I immersed myself in the scientific literature, starting with the introduction of antipsychotics into asylum medicine in 1955. The research record told of the following:

- There was no evidence that schizophrenia outcomes improved following the introduction of antipsychotics. Indeed, in a prominent study that addressed this question, researchers reported that psychotic patients treated in 1967 with antipsychotics relapsed more frequently than a similar cohort treated in 1947 and were much more socially dependent.

- With questions swirling about the merits of these drugs, the NIMH funded three studies in the 1970s that sought to assess the impact of antipsychotics over longer periods of time (one to three years.) All reported superior outcomes for the cohorts treated without antipsychotics, or with a selective-use model that minimized their use.

- As a result, leading figures at the NIMH worried that neuroleptics might be worsening long-term outcomes. Jonathan Cole, who had been the director of the NIMH’s Psychopharmacology Service Center, co-authored a paper titled “Maintenance Antipsychotic Therapy: Is the Cure Worse Than the Disease?” William Carpenter, who had conducted one of the three studies, raised the possibility that the drugs induced a change in the brain that made patients more biologically vulnerable to psychosis than they would have been in the “normal course” of the disease.

- Two Canadian researchers then provided a biological explanation for why that appeared to be so. Antipsychotics blocked dopamine receptors in the brain, and in response, the brain’s postsynaptic neurons, in an effort to maintain a homeostatic equilibrium, increased the density of their receptors for that molecule. Antipsychotics, they wrote, induced a “dopamine supersensitivity” that could lead to more frequent and severe psychotic symptoms.

That history told of how antipsychotics were not improving long-term outcomes for those diagnosed with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders. Researchers were also failing to find evidence that schizophrenia was caused by a lesion in the dopaminergic system. In 1994, John Kane, a prominent schizophrenia researcher, confessed that “a simple dopaminergic excess model of schizophrenia is no longer credible.”

Finally, I used a Freedom of Information request to get copies of the FDA’s reviews of risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine (the atypical antipsychotics.) Those reviews told of how the clinical trials of the new drugs had been “biased by design” to make them look good in comparison to the first-generation antipsychotics. As such, the FDA reviewers concluded there was no evidence they were more effective or had fewer adverse effects than the older drugs.

As for schizophrenia being validated as a discrete disorder, Nancy Andreasen, who was then editor-in-chief of the American Journal of Psychiatry, aptly summed up the state of uncertainty in research circles at the close of the 1990s: “Someday in the twenty-first century, after the human genome and the human brain have been mapped, someone may need to organize a reverse Marshall Plan so that the Europeans can save American science by helping us figure out who really has schizophrenia or what schizophrenia really is.”

Mad in America presented readers with a “counter-narrative” that told of how psychiatry’s own research, which could be dug out from the research literature, did not support the story of great progress that psychiatry had been telling the American public ever since it published DSM III. There was an extraordinary gap between what the profession was telling the public and the story that was present in the research literature.

That was the journalistic principle present in Mad in America: my job was to make known the science, and document that gap between the science and the story being told to the public.

The Test of Mad in America

As might be expected, I did experience some harsh criticism from those within the psychiatric field after Mad in America was published. E. Fuller Torrey quickly turned to the Scientology slur, that it seemed that I had fallen under the influence of Scientologists. Another review called it one of the most “disingenuous books” ever written, stating that it was impossible to claim that antipsychotics had not dramatically improved the lives of those with schizophrenia.

As the book did provide a counter-narrative to the story of great advances in psychiatry, there were two possibilities that awaited. One was that new studies would be reported that validated the story of great progress that had been told to the public. Perhaps there would be new findings of dopaminergic lesions in the brain and evidence that the second-generation antipsychotics minimized the harmful effects of those lesions. And perhaps studies of the longer-term outcomes of schizophrenia patients would show that antipsychotic use led to much higher recovery rates.

The other possibility was that the science of the past would prove predictive of the science of the future, and the great advance story would finally come tumbling down, with leaders in the field acknowledging that to be so.

A quick review can tell which of those two possibilities came true.

1) The validity of DSM diagnoses

There is now widespread acknowledgement that research since 1980 failed to validate the diagnostic categories in the DSM. Such confessions have come from Allen Frances, who was the chair of the DSM-IV task force; Nancy Andreasen, editor-in-chief of the American Journal of Psychiatry, and former NIMH director Thomas Insel, among others. My favorite quote comes from Nassir Ghaemi, at the Tufts Medical School Department of Psychiatry, who wrote in 2013:

“When I graduated a generation ago, I accepted DSM-IV as if it were the truth. I trusted that my elders would put the truth first, and then compromise for practical purposes when they had no truths to follow. It took me 2 decades to realize a painful truth, spoken now frankly by those who gave us DSM-III when Ronald Reagan was elected and DSM-IV when Bill Clinton was president: the leaders of those DSMs don’t believe there are scientific truths in psychiatric diagnosis—only mutually agreed upon falsehoods. They call it reliability.”

Former NIMH director Steven Hyman was equally succinct: The DSM is “totally wrong . . . an absolute scientific nightmare.”

2) The chemical imbalance theory of mental disorders

Although the public was stunned in 2022 when Joanna Moncrieff and colleagues reported that there was no good evidence for the low serotonin theory of depression, leading figures in American psychiatry, in their own textbooks and publications away from the public glare, had long since admitted that there was a lack of evidence that supported the chemical imbalance theory. Such declarations can be found in the American Psychiatric Association’s 1998 Textbook of Psychiatry, in Stephen Stahl’s 2000 Essential Psychopharmacology, in Steven Hyman’s 2001 book Molecular Neuropharmacology, in a 2010 paper by Eric Nestler, in a 2011 blog by NIMH director Thomas Insel, and, most famously, in a blog that same year by Ronald Pies, editor of Psychiatric Times. He wrote that the chemical imbalance “notion was always a kind of urban legend—never a theory seriously propounded by well-informed psychiatrists.”

The most succinct epitaph for this research came from Kendler, co-editor in chief of Psychological Medicine, in 2005: “We have hunted for big simple neurochemical explanations for psychiatric disorders and not found them.”

3) The superiority of atypical antipsychotics

Once olanzapine and risperidone came to market, studies that weren’t funded by the pharmaceutical companies quickly challenged the “better than the old drugs” claim. A 2000 review of 52 randomized trials concluded that “there is no clear evidence that atypical antipsychotics are more effective or are better tolerated than conventional antipsychotics.” A 2003 review by researchers at the US Department of Veterans Affairs found that olanzapine did “not demonstrate advantages” compared with haloperidol in “compliance, symptoms, extrapyramidal symptoms, or overall quality of life.” Then, in 2005, the CATIE bombshell landed.

CATIE was a NIMH study that randomized schizophrenia patients either to one of four atypicals or to an older, low-potency antipsychotic, perphenazine. At the end of 18 months, there was no significant difference between the older drug and three of the four atypicals (olanzapine was seen as slightly better than perphenazine.) Even more worrisome, neither the new drugs or the old drug could be said to work, as 74% of the 1,432 patients were unable to stay on the medications to the end of the trial, mostly because of their “inefficacy or intolerable side effects.” All of this led two British researchers, Peter Tyrer and Tim Kendall, to write in Lancet of the “spurious advance of antipsychotic drug therapy.”

“What was seen as an advance 20 years ago—when a new generation of antipsychotic drugs with additional benefits and fewer adverse effects was introduced—is now, and only now, seen as a chimera that has passed spectacularly before our eyes before disappearing and leaving puzzlement and many questions in its wake . . . As a group they are no more efficacious, do not improve specific symptoms, have no clearly different side-effect profiles than the first-generation antipsychotics, and are less cost effective. The spurious invention of the atypicals can now be regarded as invention only, cleverly manipulated by the drug industry for marketing purposes and only now being exposed. But how is it that for nearly two decades we have, as some have put it, been beguiled into thinking they were superior?”

That piece was published in 2009. While the research community may finally have had the scales removed from their eyes, readers of Mad in America had long known of this “spurious invention of the atypicals.” The evidence was there all along in the clinical trial reports that had been submitted to the FDA by the makers of these drugs in the 1990s.

4) On the long-term impact of antipsychotics

As those elements of the “great advance” narrative fell apart, the field still remained insistent that antipsychotics provided a long-term benefit and were an essential treatment for those diagnosed with schizophrenia. That belief remains. The drugs “reduce the risk of relapse,” and maintenance treatment remains the standard of care.

However, the scientific literature continued to tell a different story.

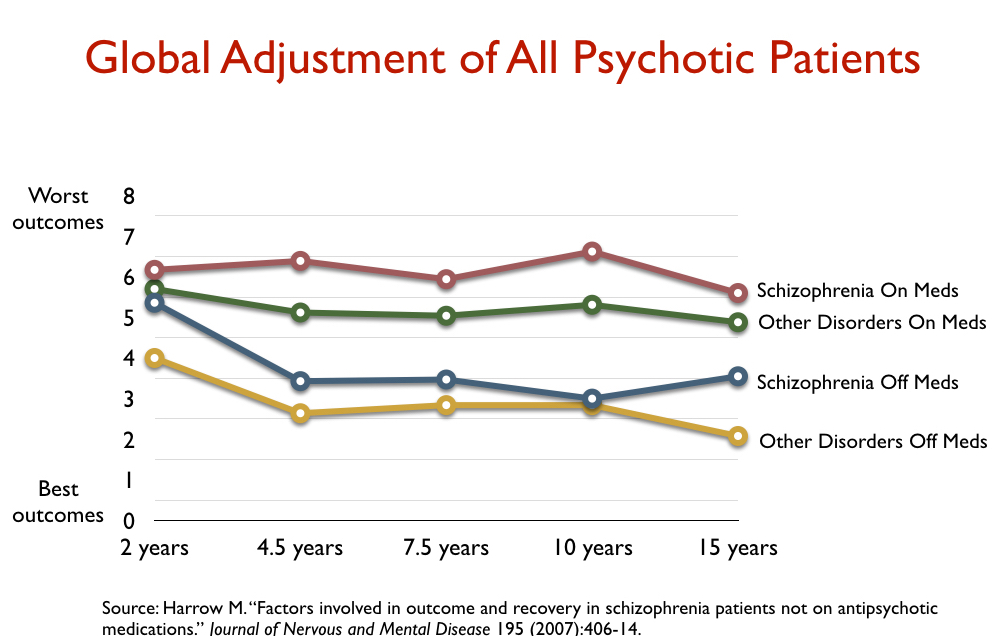

There were two NIMH-funded research projects that most powerfully countered that mainstream belief. The first was the longitudinal study conducted by Martin Harrow and Thomas Jobe. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, they enrolled 200 psychotic patients, most of whom were suffering either a first or second episode of psychosis, into their study. At the end of 15 years, they still had 145 in their study: 64 with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and 81 with milder forms of psychosis. In 2007, they reported that the recovery rate at the end of 15 years was eight times higher for those off antipsychotic medication than for those on the drugs.

“I conclude that patients with schizophrenia not on antipsychotic medication for a long period of time have significantly better global functioning than those on antipsychotics,” Harrow told the audience at the 2008 annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

The same was true for those with milder psychotic disorders. Those who stopped taking antipsychotics had significantly better outcomes. And perhaps most notable of all, those diagnosed with schizophrenia who stopped taking antipsychotic medication had better long-term outcomes than those with milder disorders who continued taking the drugs.

Over the next decade, Harrow and Jobe continued to document this disparity in outcomes related to antipsychotic use, and as they did so, they returned to the dopamine supersensitivity theory for why this might be so. “How unique among medical treatments is it that the apparent efficacy of antipsychotics could diminish over time or become ineffective or harmful,” they wrote in 2013. “There are many examples for other medications of similar long-term effects, with this often reoccurring as the body readjusts biologically to the medications.”

The other research project that so upset conventional wisdom was Nancy Andreasen’s MRI study, which charted changes in brain volumes in 542 first-episode schizophrenia patients. In 2003 and 2005, she reported that there was a “progressive reduction in frontal white matter volume” over time, and that this shrinkage was associated with a worsening of negative symptoms, functional impairment, and cognitive decline.

In those reports, she attributed this shrinkage to the disease, describing schizophrenia as a “progressive neurodevelopmental disorder” that antipsychotics unfortunately failed to arrest. However, a study in macaque monkeys had found that such shrinkage was drug-caused, and in 2011, Andreasen reported that the drugs indeed had this effect. The first-generation antipsychotics, the atypicals, and clozapine were all “associated with smaller brain tissue volumes,” and such shrinkage was dose-related, she wrote.

Her research powerfully revealed an iatrogenic process at work. Antipsychotics block dopamine activity in the brain and this leads to brain shrinkage, which in turn is associated with a worsening of negative symptoms, functional impairment, and cognitive function.

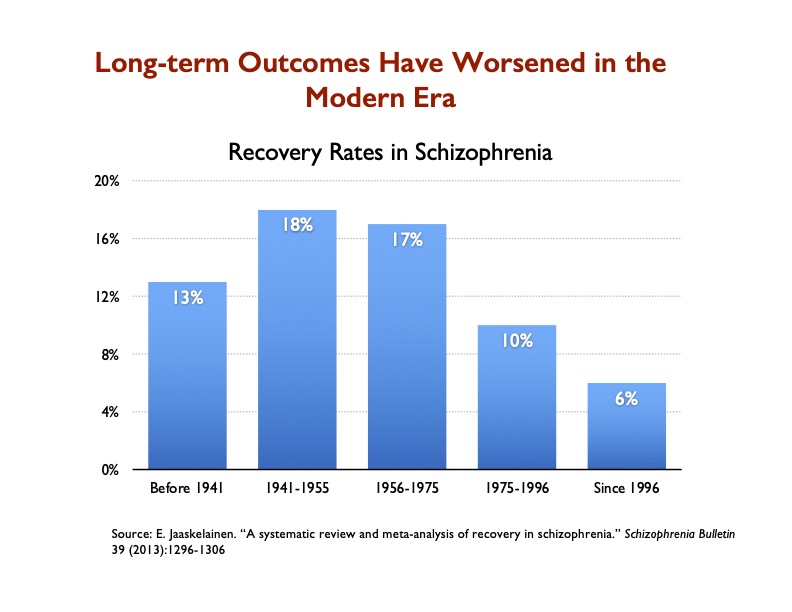

There are a number of other studies that could be cited today as evidence that antipsychotics worsen long-term outcomes and reduce recovery rates. Indeed, in 2013, Finnish investigators published a systematic review of historical recovery rates for schizophrenia patients, and their data showed that they had steadily declined since the introduction of antipsychotics, and notably so since the introduction of atypicals in the mid-1990s, with the recovery rate dropping to 6%, the lowest it has ever been.

The American Psychiatric Association and “thought leaders” in American psychiatry have mostly avoided addressing this research, or, if so, they have sought to discount it. However, in 2012, the British Journal of Psychiatry, in an editorial by Peter Tyrer titled “The End of the Psychopharmacology Revolution,” stated that the time had come to rethink the use of antipsychotics. He wrote:

The American Psychiatric Association and “thought leaders” in American psychiatry have mostly avoided addressing this research, or, if so, they have sought to discount it. However, in 2012, the British Journal of Psychiatry, in an editorial by Peter Tyrer titled “The End of the Psychopharmacology Revolution,” stated that the time had come to rethink the use of antipsychotics. He wrote:

“It is time to reappraise the assumption that antipsychotics must always be the first line of treatment for psychosis. This is not a wild cry from the distant outbreak, but a considered opinion by influential researchers . . . [There is] an increasing body of evidence that the adverse effects of [antipsychotic] treatment are, to put it simply, not worth the candle.”

Maryland psychiatrist Ann Silver, in a 2009 interview, summed up the change wrought by antipsychotics in this memorable way: “In the nonmedication era, my schizophrenic patients did far better than do those in the more modern era. They chose careers, pursued them, and married. In the [later] era, none chose a career, although many held various jobs, and none married or even had lasting relationships.

The Founding of madinamerica.com

It is not surprising that the story that American psychiatry told to the public during the 1980s and 1990s subsequently fell apart. There were never scientific findings that supported that tale of breakthrough discoveries and treatment, and it is difficult to maintain a false narrative forever.

After Mad in America was published, I wrote two other books of non-fiction, and then in 2010, I published Anatomy of an Epidemic. That book sought to investigate this question: How do psychiatric drugs affect the long-term course of major psychiatric disorders? The public assumption at that time was that they do provide a long-term benefit, and public belief in the chemical imbalance provided a reason that would be true.

However, the short answer to that question is that there is a coherent body of research findings related to four major disorders—schizophrenia, depression, bipolar, and ADHD—that tell of how the medications increase the likelihood that patients will become chronically ill and functionally impaired.

In that book, I also documented how findings that tell of harm done are never promoted to the public by psychiatry or included in psychiatry’s own textbooks. For instance, even today I have never seen any report of Harrow’s longitudinal findings in a major American newspaper.

That absence was a primary motivation for founding madinamerica.com. When Kermit Cole, Louisa Putnam, and I launched the website in January 2012, we wanted it to serve as a forum that would make such research known. We would provide reviews of research findings that weren’t being promoted to the public, and in this manner we would seek to provide the public with “informed consent.”

We have been at this for more than 10 years now, and our science coverage has grown such that we now provide five science reviews per week. We also publish in-depth reports on such scientific findings. You can search through our science archives, and you will find a wealth of research findings that have gone missing from the mainstream media: studies on the long-term outcomes of medicated patients; risks of using antidepressants during pregnancy and possible harm to fetal development; drug withdrawal findings; the lack of validity of DSM diagnoses; the STAR*D fraud; and so forth. The “evidence base” on these topics continues to collect and grow, and we now have a global audience for this information. We had around six million visitors last year, and we now have 15 affiliate “Mad in the World” sites, which increasingly republish our science reviews.

That is the story of what we seek to do with our science coverage. We strive to make known research findings that are missing from the mainstream media and yet need to be known.

Now we can turn to our reporting on the genetics of schizophrenia, which, as I wrote above, can serve as a test of our science coverage on this topic, with Kendler’s piece in JAMA Psychiatry as a foil for comparison.

Kendler’s Viewpoint in JAMA Psychiatry

Kenneth Kendler is the director of the Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, and a long-time editor of Psychological Medicine. He is known in particular for his research on the genetics of schizophrenia, and as the BJPsych Bulletin noted in 2020, he is the second most highly-cited psychiatric researcher in the world.

He also has been one who, in fact, has poked holes in the story of progress told to the public. As noted above, in 2005, he told of how the search for chemical imbalances in the brain had not born fruit. In a 2021 paper published in JAMA Psychiatry, he added his voice to those who had spoken of how the DSM diagnoses lacked validity.

In his February “viewpoint” published in JAMA Psychiatry, he addressed what he calls a “vexing” question in psychiatry: “Are Psychiatric Disorders Brain Diseases?”

Starting in the 19th century, he writes, this involved looking for “detectable pathology in the brain.” As no such characteristic pathologies have been found for psychiatric disorders, Kendler argues that way forward for psychiatry is to “turn instead to a more modest but more tractable question—can we show that critical causal pathways to psychiatric illness occur in the brain?”

He then begins his argument with the assertion quoted at the beginning of this essay: “To proceed, I use the most robust empirical findings in all of psychiatry—that genetic risk factors impact causally and substantially on liability to all major psychiatric disorders.”

Kendler cites a 2020 book he co-authored, “How Genes Influence Behavior,” as the source for his assertion. However, in his essay, he also cites a 2022 article by the Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, which opens with this declaration of fact: “Schizophrenia has a heritability of 60 to 80%, much of which is attributable to common risk alleles.”

With that “fact” as a starting point, Kendler lays out his argument. Many human genes, he writes, are “expressed only in specific tissues, and for a goodly number, only in the brain.” That, he explains, is the case with some risk genes for schizophrenia. In their 2022 report, the Schizophrenia Working Group found that there was an “elevation” in the expression of “schizophrenia-risk genes” in 11 brain tissues, but not in other parts of the human body. As such, Kendler concludes, the field can now “claim that the effect of the strongest known risk factor for schizophrenia—genetics—largely occurs in brain tissue.”

The discordance between Kendler’s viewpoint and our MIA Report is this: Has research shown that genetics is the strongest known risk factor for schizophrenia?

Mad in America on the Genetics of Schizophrenia

During the past decade, Mad in America has published reviews of a number of research findings regarding the genetics of schizophrenia. Peter Simons’ MIA Report was prompted by a recent paper by E. Fuller Torrey, in which Torrey—a prominent promoter of the concept that schizophrenia is a “brain disease”—compared the search for schizophrenia genes to a “wild goose chase.” Twenty-five years of genetics research, Torrey concluded, had failed to find any meaningful genetic associations, with high-profile initial claims of such findings regularly failing to be replicated in further investigations. “Schizophrenia does not appear to be a genetic disorder,” Torrey concluded.

In his MIA Report, Simons detailed Torrey’s review of the genetics research, and then also reviewed many of the research findings that can be found in our science archives on this topic. In particular, he cited studies that assessed the “impact” of risk genes on the likelihood of developing schizophrenia. Here are the principal articles he referred to:

2014: A study in Lancet Psychiatry found that environmental risk factors (i.e., perinatal brain insults, cannabis use, neurotrauma, psychotrauma, urbanicity, and migration) were a “major risk factor for early onset schizophrenia,” while “polygenic genome-wide association study risk scores did not have any detectable effects on schizophrenia phenotypes.”

2015: In Molecular Psychiatry, researchers concluded that “the current empirical evidence strongly supports the idea that the historical candidate gene literature yielded no robust and replicable insights into the etiology of schizophrenia.”

2017: In Biological Psychiatry, researchers concluded that “taken as a group, schizophrenia candidate genes are no more associated with schizophrenia than random sets of control genes.”

2019: Researchers reviewing “genome-wide association studies,” which have found statistically significant associations between large gene sets and a schizophrenia diagnosis, determined that these associations explained 2.28% of the risk that a person will be diagnosed with schizophrenia. That left other risk factors, such as the environment’s impact on biology, emotional trauma, and childhood experiences constituting nearly 98% of the risk. The study was published in Neuropsychopharmacology.

2020: In Schizophrenia Bulletin, researchers reported that sequencing the exome (a particular set of genetic information) provided no clinically relevant data for making a schizophrenia diagnosis. “The main conclusion of this investigation is a negative one,” they wrote. “The diagnostic yield for exome sequencing of known neuropsychiatric genes in this sample is about 1%.”

2020: Researchers from the Netherlands, writing in Schizophrenia Bulletin, reported that familial and environmental factors account for most of the risk of developing schizophrenia, and that genetics constitute a risk factor of about 0.5%

2021: A study of 50,000 people, which was published in the Journal of Affective Disorders, failed to find any genes that influenced mental illness. “The results obtained from this study are completely negative,” the authors wrote. “No gene is formally statistically significant after correction for multiple testing, and even those which are ranked highest and lowest do not include any which could be regarded as being biologically plausible candidates.”

The 2019 study published in Neuropsychopharmacology is of particular relevance here. The authors analyzed data sets produced by the Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium in order to quantify the impact the risk gene variants had on schizophrenia diagnoses. Here is an excerpt of our review of that study, which we published in 2019:

Although genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have found statistically significant associations between large gene sets and the schizophrenia diagnosis, the researchers write that existing studies do not clarify how much the statistically significant findings matter. “These analyses do not estimate the contribution of these gene sets to the amount of variance explained,” according to Nicodemus and Mitchell.

Nicodemus and Mitchell wanted to correct this oversight. Working with the Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, they gained access to the datasets for 39 studies, including 29,125 people diagnosed with schizophrenia and 34,836 people without a diagnosis (all of European ancestry).

The researchers took this data and assessed how much predictive power the genetic associations had. Their research asks, how well could you predict whether someone has a diagnosis of schizophrenia if you knew their entire genome? Their results suggest that the genetic associations explain very little.

The researchers studied several commonly cited contenders, sets of genes like TCF4, FMRP, MIR137, and CHD8. They also looked at sets of genes that are associated with cancer and cardiac problems, for comparison. All told, the statistically significant genetic associations explained a total of 2.28% of whether a person is diagnosed with schizophrenia. That leaves a solid 97.72% to be explained by other factors, such as the environment’s impact on biology, emotional trauma, childhood experiences, or family dynamics.

The TCF4 set of genes has been the most studied candidate to explain the heritability of schizophrenia. According to Nicodemus and Mitchell, this set was the most significantly associated with a diagnosis. In 29 of the 37 studies that analyzed it, it was found to be associated with schizophrenia (it was found not to be associated with schizophrenia in the other eight studies). In all, this particular set explained 0.6% of whether someone had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or not.

Other sets of genes explained even smaller percentages of the variance in outcome. For instance, FMRP explained 0.43% of the variance and was associated with schizophrenia in 23 of the 39 studies (not associated in the other 16). MIR137 and CHD8 fared even worse.

Thus, if you incorporate these findings into Kendler’s argument, you understand that while researchers may have found that there are polygenic variants that are associated with a schizophrenia diagnosis, these gene-mediated pathways in the brain have very little impact on increasing the risk that people will develop schizophrenia. Trauma, public health environments, and other environmental factors have been found to have the biggest impact on “liability” to a schizophrenia diagnosis.

Making Known the Little Known

It is well known that once a scientific finding is embraced as “fact,” a scientific or medical discipline will resist findings that challenge that fact. Cognitive dissonance sets in, and the newer findings are dismissed as flawed in some way, or simply ignored. While the discordant findings may be published, they will likely be given little attention by others, and the corrective they provide to the conventional belief is lost.

For instance, the 2019 study published in Neuropsychopharmacology has been cited only 23 times, with an altmetric score of 18—a low score that tells of it being little discussed. There have been 8,133 people who have “accessed” the article, and there is no account of any media coverage of it. In contrast, Kendler’s essay, which was published only 10 days ago, has an altmetric score of 205 and more than 8,400 have accessed it.

As far as I know, Mad in America is the only “media” that reported on the 2019 article in Neuropsychopharmacology, and our MIA Report is surely the first time the finding has been incorporated into a review article, meant to be accessible to lay readers, on the “genetics” of schizophrenia. Our report, I am pleased to say, has been accessed more than 74,000 times.

And here is why this is important: the corrective to the “fact” that schizophrenia is in large part a “genetic” disease leads to a reconceptualization of the nature of the disorder, and what treatments may be of most help. The genetics conception leads to a search for treatments that can, in some manner, counteract the impact of the “faulty” genes. The conception also suggests it is bound to be a permanent state—you can’t change a person’s genetic makeup when hundreds or thousands of genes are said to confer the increased risk. But if environmental factors confer most of the risk, then it is reasonable to develop treatments that are responsive to those factors. This conception also provides hope for a full recovery from an episode of “schizophrenia.”

As I wrote at the start of this essay, this review could provide a test of whether our science coverage provided readers with a more robust knowledge of the research on the genetics of schizophrenia than the conventional understanding present in the JAMA Psychiatry essay by Kenneth Kendler. And here is the bottom-line difference: Whereas readers of the JAMA Psychiatry essay would be reminded of the “fact” that hereditary factors account for 60% to 80% of the risk for developing schizophrenia, our readers are reminded that studies have found that these gene variants account for perhaps 2% to 3% of the risk.

That’s a notable difference, and that tells of our motivation for reporting on research findings that otherwise would go unnoticed by the general public, and, if truth be told, go unnoticed in most corners of the psychiatric community.

Hi Robert,

I’m a long-time supporter (I have an autographed copy of “Anatomy of an Epidemic”). I’m also a long-time reader of a blog written by psychiatrist Scott Alexander. The blog is called Astral Codex Ten (formerly Slate Star Codex) and covers many topics besides psychiatry. While I don’t necessarily find his psych-related posts to be convincing, they seem more reasoned and thoughtful than most of what I encounter from conventional sources.

I wonder if you’ve seen his recent posts on the genetics of schizophrenia:

https://www.astralcodexten.com/p/some-unintuitive-properties-of-polygenic

https://www.astralcodexten.com/p/its-fair-to-describe-schizophrenia

I found them to be interesting, and I’m curious if you have any thoughts about the arguments he makes (as much as I would love to go down these rabbit holes myself, I have other responsibilities that limit my time).

Keep up the good work!

Report comment

On the first one:

It is pretty bad logic.

1) He has the hidden assumption that we can actually identify schizophrenia, but even under the assumption that schizophrenia exists, we know that most people with a schizophrenia diagnosis wouldn’t be schizophrenic and most schizophrenics wouldn’t have a schizophrenia diagnosis, as sensitivity and sensibility of the diagnostic progress is so poor.

2) It’s what we call a Milchmädchenrechnung, a milk maids calculation/bill, in german. An oversimplyfied calculation that leads to wrong results, because it leaves out how genetic factors can cause environmental factors. Consider drapetomania, a “disorder” that would show up as highly genetic, as only black people can “have” it. Obviously it would not actually be genetically caused but by racism on a societal level.

On the second:

I think he is wrong in his comparision between smoking causing lung cancer and genes causing schizophrenia on three levels:

He acknowledges that all theories are wrong to some extend. I agree. F=MA is “wrong” on the relativistic and quantum scale, but it is right and useful on the huge scale between thoose. Saying smoking causes lung cancer is both right on a bigger scale and more useful than saying genes cause schizophrenia.

Firstly you are right way more often when you describe a lung cancer as being caused by smoking than when you describe schizophrenia as being caused by genes, although we wouldn’t even have a test for the latter.

Secondly it’s way more useful, as getting people to stop smoking would prevent lots of lung cancer cases. A genetic test for schizophrenia would do what excactly? Some kind of eugenics program where hundreds of high risk children would be aborted to prevent a single case of schizophrenia? It just has zero utility at current sensitivity and sensibility levels.

Thirdly smoking causing lung cancer actually is embedded into a bigger understanding of cancer, while schizophrenia is genetic has a gaping void between some genes being associated with schizophrenia and it being diagnosed.

Report comment

Schizophrenia doesn’t even exist :

1.)As defined by the DSM-5– the concept is so diffuse as to be meaningless,in the scientific context. That means that two different patients can be diagnosed with two non-overlapping sets of symptoms.

2.) during the DSM-5 field trials, which the DSM-5 in general, flunked, it i needed a .70 or above to have a satisfactory or better intra-reliability statististical kapppa score : but it scored an unreliable .45.

If a concept is too diffuse to be meaningful in the scientific context, and is mathematically unreliable –it is a fool’s errand to look for brain defect correlates or genetic defects in SNPs. Scientifically speaking it is game over :

Schizophrenia does not exist !

Report comment

Kevin Francis Burke, Robert Whitaker,

What is the obsession with Schizophrenia or any other Schiz? Yet another fabrication that puts very important psychiatric practitioners in charge.

Most rational and logical and wise people know that the majority of mental ill-health is a by-product of poor nutrition, poor sleep quality not necessarily due to social and or financial situations.

How many drugs, licit, taken as recommended and or instructed are known to cause disturbances, disruptions, alterations, modifications, “adaptations”, (the list for harms is long) …. affecting sleep, appetite ? Add to these two known adverse reactions the effects that they alone have on every other system and cell in the human body, and voila, a profiteering dream come true. As for cause and correlation – research is set up in such ways that temporal proof can rarely be demonstrated. And, how on earth, in all rationality, can a dead brain demonstrate anything at all when it comes to the workings of the living brain ? ! More specualtions ? More hypotheses ? More of anything as long as it rakes in the Big Money .

Report comment

Whitaker at Mad in America (MIA) recently published a blog post – “Putting JAMA Psychiatry and MIA to the Genetic Test” (March 13, 2024) – that has left me perturbed. MIA, as many readers will be aware, is a website devoted to critical coverage of psychiatry. I have previously written about how the website is committed to portraying psychiatry as a failed discipline. Whitaker’s new post is prompted by a recently published viewpoint article by Kenneth Kendler in JAMA Psychiatry (which I also discussed in a prior post). Whitaker believes that this presents an opportunity for him to highlight MIA’s rigorous and unbiased coverage of psychiatric genetics over the years. The only problem is that MIA’s coverage of psychiatric genetics is anything but rigorous and unbiased. It is highly selective, and it distorts or ignores basic facts about genetics that are necessary to keep one tethered to a sensible scientific worldview. The average MIA reader doesn’t have the necessary background knowledge, familiarity with the scientific literature, or access to the relevant articles to identify the problems. AWAIS AFTAB

MAR 22

Report comment

Are you saying that you support the idea that real mental problems can be caused by genetic transmission?

Report comment

It wasn’t clear to me at first, but Robert Farra (above) is quoting from the following blog post, written by psychiatrist Awais Aftab:

https://www.psychiatrymargins.com/p/how-mad-in-america-misrepresents

Report comment

If Awais Aftab felt secure in the results of psychiatry’s genetic research, he wouldn’t bother reacting to articles in MIA that highlight the dubious nature of psychiatry’s genetic research results. It’s as simple as that. The fact that Awais does react suggests he harbors feelings of inadequacy around the subject, which is easy to understand considering how cobbled together (and ultimately speculative) the research results are.

In common parlance, Awais seems ‘triggered’ by certain people who dare call out psychiatry’s vacuous claims of genetic risk or causality. IMHO.

Report comment

If Awais Aftab felt secure with the results of psychiatry’s genetic research, he wouldn’t bother reacting to articles in MIA that highlight the dubious nature of psychiatry’s genetic research results. It’s as simple as that, imo. The fact that Aftab does react imo suggests he harbors feelings of inadequacy around the subject, which is easy to understand considering how cobbled together, speculative and therefore essentially inconclusive the research results are.

Putting it more simply, Awais Aftab seems ‘triggered’ when reputable people like Robert Whitaker dare call out psychiatry’s dubious claims of genetic risk or causality regarding psychiatry’s equally dubious “DSM diagnoses”.

Report comment

Awais Aftab has attacked us and me numerous times, and it is easy to show that he he hurls accusations that are easily refuted, as is the case with this one. I am traveling now, and will respond when I return in April. But quickly, a) our MIA Report by Peter Simons was triggered by an essay by E. Fuller Torrey that the search for schizophrenia genes had turned out to be a wild goose chase, and our MIA report reviewed the very research that Torrey had cited. Second, in my blog, it is easy to show that we accurately cited this study:

2019: Researchers reviewing “genome-wide association studies,” which have found statistically significant associations between large gene sets and a schizophrenia diagnosis, determined that these associations explained 2.28% of the risk that a person will be diagnosed with schizophrenia. That left other risk factors, such as the environment’s impact on biology, emotional trauma, and childhood experiences constituting nearly 98% of the risk. The study was published in Neuropsychopharmacology.

If you look at the study, you’ll see there are very small risks associated with six different gene sets related to schizophrenia, and that together the six risks add up to a total 2.28%

Again, I’ll write more, but this is just more of Aftab hurling accusations that are easily refuted.

Report comment

Robert Farra,

Do you want there to be “psychiatric genetics” ? If so, for your research you will need to find and study human beings who have never been exposed to immunisations, vaccinations, medications, medical substances, medical treatments, and any other exogenous poisons, toxins, and so on.

Such humans would have ancestors who also were never subjected to any exogenous interventions. Now, there are in fact such people to be found, but not for long, because they too are being invaded by modern impulses and urges that are too uncontrollable to leave well enough alone.

Aside from greed and money and profits why would you want people to be sick? Why would you want to make them to be unwell?

Report comment

Excellent!

Report comment

Extraordinario leer este tipo de información sumamente importante ,yo hace poco conocí esta pagina y he tenido la oportunidad de leer una gran cantidad de informes aquí publicados. Aquí en Colombia me atrevo a decir que ningún profesional de la salud conoce toda esta información.

Report comment

Thank you Robert as always for an interesting read.

And thank for keeping exposing the pseudoscience that is psychiatry and giving those harmed by them a voice.

Report comment

“Schizophrenia Is Not Genetic,” but it is likely largely iatrogenic. Given the reality that the antipsychotics / neuroleptics can create the positive symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via anticholinergic toxidrome. And the so called “schizophrenia treatments” can also create the negative symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome

Report comment

Someone Else, Robert Whitaker,

The DSM is a collection of symptoms. Those symptoms are similar if not the same as the side effects, adverse effects of prescribed medications taken as prescribed. “Substances” included. Treatments ought to be included. Symptoms described in the DSM also cover the majority of symptoms that occur with the majority of physical illnesses and infections. So everything points to mental disorders. The DSM has all bases, outfields, and other positions by consensus, covered. Ingenious. Iatrogenic harms probably also nicely fit in with mental disorders’ symptoms.

Report comment

I enjoyed this article on schizophrenia and genetics, but I want to comment on a side issue in this piece, the uselessness of the DSM.

An article in the Wall Street Journal this week claims that ultra processed foods (not clearly defined) have an effect on the brain so some researchers are proposing that a new mental-health condition be added to the psychiatric bible. They want to call it ultra-processed food use disorder.

You can’t make this stuff up.

Report comment

I don’t see the uslesness of the DSM as as side issue at all. As you shall see here, if staff here are kind enough to let my first post through. I hit schizophrenia— head on target –though.

Report comment

Some mental health professionals also wanted to add “pandemic disorder” to the DSM because that’s what people were coming to them for.

I honestly wasn’t against it. Then people woudln’t be diagnosed with other mental illnesses for something situational and then maybe the public would start putting together that diagnosis is just the word they use for why you came to see them.

Yes they are real problems, no they are not brain diseases (at least that we know of.)

Report comment

“In their 2022 report, the Schizophrenia Working Group found that there was an ‘elevation’ in the expression of ‘schizophrenia-risk genes’ in 11 brain tissues, but not in other parts of the human body. As such, Kendler concludes, the field can now ‘claim that the effect of the strongest known risk factor for schizophrenia—genetics—largely occurs in brain tissue.”

There are three fundamental truths that the oh-so eminent Kenneth Kendler fails to see:

1. Just because it’s cloudy doesn’t mean it’s raining

2. Even science has its limitations

3. Like everyone else, medical researchers are vulnerable to the hazards of wishful thinking, e.g., the attribution of reality to what one wishes to be true or the tenuous justification of what one wants to believe.

Report comment

— courtesy Merriam Webster.

Report comment

I’m running for Congress in West Virginia. As someone who has worked with at-risk youth for twenty plus years, I couldn’t help but notice that said youth is prescribe a ton of psychiatric drugs. Mad In America has done yeoman’s work highlighting the scientism that undergirds biological psychiatry-thus far this knowledge hasn’t impacted the rate of psychiatric prescribing of these drugs to youth in my neck of the woods. In order to call attention to the matter, I’m calling for Congressional hearings.

Report comment

I think Congressional hearings on the prescribing of psychiatric drugs to at-risk youth is desperately needed.

Report comment

I don’t exactly know how to get the ball rolling on this subject. It is a difficult subject. All of us encounter the routinized process of passing medications to the children at the child shelter where I work. The staff seem genuinely concerned about the welfare of the children. I take solace in the fact that none of my coworkers are prescribers.

Report comment

I wish we had a “thumbs-up” option for comments. I just want to say that I agree – we need congressional hearings on the use of Rx drugs for at-risk youth.

Report comment

I think the best thing we can do for youth with a mental disorder is to have them treated by a professional homeopath. That’s what I did for my son who was diagnosed with “incurable” “bipolar with psychosis.” The right remedy (homeopathic medicine) cured him very quickly, gently, permanently and with no side effects. That was almost 10 years ago. Homeopathy then cured another relative of “incurable” “schizophrenia” which, like my son’s “bipolar,” turned out to be caused by Toxoplasmosis. The World Health Org (WHO) says that homeopathy is the second most widely used system of medicine in the world. It’s truly amazing. – Linda, author of “Goodbye, Quacks – Hello, Homeopathy!”

Report comment

Thank you for another scientific journalism masterpiece Robert Whitaker. Further insight into those who are so consistently: – “Economical With The Truth”.

Report comment

“To proceed, I (Kenneth Kendler) use the most robust empirical findings in all of psychiatry—that genetic risk factors impact causally and substantially on liability to all major psychiatric disorders.”

That alone says a bit much.

It’s pathetic the way psychiatrists like Kenneth Kendler cling to flimsy ‘evidence’ that indicates essentially nothing. But that’s to be expected from careerists like Kendler who have a lot to lose professionally, socially, and financially if they dare step out of line too much or too often. People like that are socialized to uphold the mainstream narrative no matter what, to always go where their bread is generously buttered—even if the churner is empty to keep alive the party line —

Report comment

Some people will say anything to keep alive a dying narrative.

Report comment

Yet another vital public service announcement from the indispensable Robert Whitaker!

I can’t help but infer from Dr. Kendler’s unflagging faith in the correlatives between gene casualty and “risk”, as pretty much a tee shot ( e.g., institutional impunity) with a 20 year fairway; which is to say 20 more years of empirically unsubstantiated claims of “proof” providing ample (future) fodder for MIA-and any other journalism outlet that values facts and human life.

Report comment

Jay Joseph’s MIA article, “The Schizophrenia Genetics Illusion: A Century of Failure and Hype,” makes a good supplement to Robert Whitaker’s excellent analysis.

In “The Selling of DSM: The Rhetoric of Science in Psychiatry,” Kirk and Kutchins point out that the creators of DSM-III had two problems to solve: validity and reliability.

In the absence of biological tests, the validity of psychiatric diagnosis remains unprovable because you do not have another test for a comparison. In other words, we have no evidence that someone labeled “schizophrenic” via the DSM in fact has schizophrenia.

So the DSM creators abandoned any attempt at proving validity and instead focused on inter-rater reliability: could several researchers agree that a person was schizophrenic. They claimed to have achieved great reliability, but Kirk and Kutchins wrote an article called “The Myth of the Reliability of the DSM.”

If we narrowed the criteria sufficiently, we could probably achieve 100% inter-rater reliability about whether a particular person is a witch. But this would have no bearing on the validity of whether this person is a witch, or even that witches exist.

Rather than a legitimate medical diagnostic manual, the DSM is more akin to palm reading or a Tarot card session: the categories are all so broad and so vague that virtually anyone can qualify for a diagnosis of some kind.

Report comment

Keith Hoeller, Ph.D.

The DSM has made possible trillions of dollars (any currency) in revenue. Which other book on the face of the planet, in history, can boast such mighty influence?

Keep the witches (likely more honest and more helpful) and put the DSM where it belongs; archived and gathering dust.

Report comment

Evidence-based treatments (Tx) require more than verifiable data which can be replicated by others, they require a correct diagnosis following a thorough differential diagnosis conducted by an unbiased clinician. In today’s profit-driven healthcare systems, time is now the limiting factor before diagnoses are assigned to patients, and they too often, go unquestioned by other doctors.

Getting a second opinion from a psychiatrist is a waste of one’s time and money, because a doctor rarely questions another doctor’s diagnostic capabilities and the diagnoses assigned. Yes, rarely questioned.

Too many inappropriate medications are prescribed for too long, and at high doses to people like me who had a verified head injury (TBI) ten years prior to first seeking psychiatric care for insomnia and PTSD.

People who have had a TBI are super-sensitive to most psychiatric medications and many medications should not be prescribed at all, such as lithium and benzodiazepines. It’s the medical standard of care to treat the underlying condition, and do no harm by refraining from aggressively treating the TBI neuropsychiatric sequelae with daily doses of antipsychotics and benzodiazepines.

Recent MRIs of my brain, (2021 & 2024) reveal its volume has shrunk and that it has many holes, something my neurologist and I were able to quip about and chuckle a bit.

Diagnostic overshadowing of physical disorders by mental health clinicians, who incorrectly attribute a new symptom(s) to a previously diagnosed psychiatric disorder, is a problem occurring as a result of bias and stigma, and in rushed and stressed clinical environments.

Late, adult-onset Multiple Sclerosis (MS) was missed since 2010 when balance problems arose. Disease modifying treatments for MS weren’t in the realm of possibilities, until everyone in the room noticed “the elephant in the room walking like a drunken sailor.”

~JLReoch

Report comment

Psychiatric drugs are radioactive imo and consequently should be treated as such.

Report comment

Peter Breggin has testified in congress regarding iatrogenic harm to military personnel, as I recall. Maybe times have changed enough that more can be done. I publicized a talk organized by Re-Thinking Psychiatry at a nami meeting many years ago. I got hissed at, but some showed up at the workshop, and one of them gushed about happy-camper bread afterwards. Some progress in all that time, but I had hoped for more-faster. Now, even free speech is challenged, yet increasing numbers are figuring things out. Thanks so much for being point-man, out in front.

Report comment

Wow! Now I am going to have to look that up. I believe you. Totally.

Report comment

I have to say that I have followed your work for years. I listened to your books on Audible and had my own nightmare in the 90’s and early 2000’s getting off psychotropic meds, but with God’s grace, after battling close to 15 yrs on this crap, I got off and have been off now almost 17 years, and I have never felt better. The psychiatrist who initially put me on the meds did it while I had been in treatment and while I had one therapist tell me that I was fine, the psychiatrist told me that it was part of being in the hospital.

Fast forward to my years in grad school, when the DSM-IV-TR version was being used and I was specifically taught in my psychopharmacology class that the DSM was just a bunch of made up diagnoses with no scientific backup and I could diagnose anyone with at least 30 of the mental disorders at any time. I also happened to go to a college where Dr. Daniel Amen was teaching at the time and he was just starting his brain scan research.

Needless to say, I tell everyone I can about your site because I will never trust another doctor who wants to shove these poisons on us. The last doctor I saw tried to push me on to anti-depressants because I was crying in the office. I told him, “Hell no, my father just died and this grief is NORMAL…” I swear.

Anyway, I am not surprised to see that your research on schizophrenia has been largely ignored and I’m also not surprised to see it’s not really genetic. Just think of all those poor people who have been messed up because of the lies. That should anger any normal non medicated human being.

Report comment

Stacy Lynn, Robert Whitaker,

It is bamboozling that some people on psychiatric drugs can study, hold down a job, make career advancements, have a partner, marriage, child, children, social engagements and family commitments – while some people fall in a heap and their lives are shattered. What makes such a huge difference? Is it money?

Do some people get better service and treatment? Do some people have certain resources that some other people don’t?

Is there a book that tells of what really goes on for some – finances, supportive other/s, ??

So who are the victims of psychiatry, the DSM, (ICD), the medical model, Pharma ? Is it desperate parents needing to work ? Who ? Single mothers ? Children of single parent with no social supports ? Who ? The vulnerable ?

The most significant factor in mental matters is the person’s financial position. So who is being preyed on ? Who ? Those who find daily pressures and strains and tensions to be tiring ? Offer no instrumental or functional help. Offer drugs !

Report comment

And the harm and damage to populations gets worse now with nearly 90% of these toxic psychiatric drugs being prescribed by non-psychiatrists like GP’s, NP’s, PA’s, neurologists, gerontologists and even psychologists! It seems that the business model is “a patient for life” and ” the worse they get the more they need u$”. The only way to stop this to a great degree is demand that tax payer supported Medicaid and Medicare insist on paying for treatment with long term evidence based outcomes. Once the spigot of $$$ is cut off then they will change their tune.

U.S. taxpayers are throwing tens of billions of dollars on nonsense treatments and research each year. Actually there is hard evidence that these anti-psychotics are killing (strokes & cardiac events) the aged and elderly at record pace all funded by U.S. taxpayers!

Report comment

Gilbert, Robert Whitaker,

Most adult children, adults do not value their “loved ones” more than the inheritance entitlement –

Many prompt the giving of psychiatric (and other) drugs, knowing that in doing so, decline will be hastened. As quality of life dwindles slowly, impatience surges rapidly.

Interesting to watch, observe. Who prescribes what, based on what information, for whom, for what reason, and when. ?

Report comment

Antipsychotics are profitable for prescribers and manufactures, but rarely are patients provided signed, informed consent documents that are signed by the prescribers and their patients. Rarely are symptoms attributed to other disorders such as TBIs, or a developing neurological condition such as Parkinson’s, Multiple Sclerosis, or even ALS.

Time.

Time to acquire a complete medical history, by reading the patient’s entire psychiatric chart is critical before continuing to prescribe drugs that should have been safely discontinued years prior, has always been insufficient.

Is the doctor/patient time allotment a convenient scapegoat for poor patient outcomes?

Could be used as an excuse, that I can see.

Can adverse effects be prevented when time isn’t minimized between the patient and prescriber?

Can tranquilized patients dig out of their memory what is improving or not, or what are new or worsening symptoms that the psychiatrists aren’t seeing that could be attributable to a medication, or medication combo?

Do doctors know which medications to never prescribe concurrently in order to prevent a neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) from occurring?

Many medication side effects aren’t recognized and others are easily dismissed. Much what must be factored into the differential Dx equations used by psychiatrists is woefully inadequate or missing entirely because of time, as are other factors such as knowledge of the prescriber and the educational level of the patient.

Referrals to other experts may be not only delayed, they may be just an after-thought for the patient with many complaints while consuming a drug cocktail of dubious benefit. Patients who must make sure that their doctor(s) isn’t causing them more harm with the drugs they’ve prescribed are the sacrificial canaries in the coal mine, because there are too many different pills to prescribe for FDA and non-FDA approved purposes.

It has become too easy to “pill someone towards more disability,” because too often, medications are prescribed for non-FDA approved purposes. Medications are now casually prescribed for an “off-label” reason. Doctors will guess what may help a patient, but are loath to generate any signed, informed consent forms documents for experimental treatments.

In my case, the first doctor prescribed a drug on a “trial basis” only to have the next doctor and the next continually prescribe it at higher and higher doses as time went by, despite no proof that the medication prescribed indefinitely (forever) continues to provide its intended benefits without new adverse risk emerging from long term use.

* Informed consent documents must be generated, signed, and reviewed semi-annually/annually to ensure safe prescribing habits are occurring by all the patients’ attending doctors and healthcare providers *

The experimental use (off-label prescribing) of any medication must be discussed with the patient and that discussion written down for both parties to acknowledge and sign before placing it in the health record. A “treatment” informed consent document must be initiated so that other doctors are fully in the loop about how a person should fare on the drug treatment plan prescribed by a healthcare professional.

Informed consent to consume a medication for off-label purposes to treat the side effect of another prescribed medication is never done, nor are all benefits & risks discussed as to why another psychotropic medication must be added to the current cocktail of three or more psychotropic drugs.

Here’s useful information for those just beginning to be drugged into more disability:

“What to Consider When Prescribing Off-Label”

ALLISON FUNICELLI, M.P.A., C.C.L.A., A.R.M.

Published Online:10 Jul 2019 https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.pn.2019.7b21

https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2019.7b21

The article explains how prescribers can protect themselves from harm. Unfortunately, the patient will assume all the risks after verbally agreeing to a doctor’s treatment orders if signed, informed consent document aren’t created for both parties to review at any given time.

The health record is for and about the patient, but the information it contains is written solely by the narrating doctors who skillfully blame time (or the patient) for the inability to enclose within the patient’s health record both parties verbal input and their signatures acknowledging informed consent to the agreed upon treatment plan for a known duration, or for a lifetime, or for as long as the patient can tolerate the treatment.

When potent, psychotropic prescription medications are abruptly discontinued, chemical torture is perceived during the withdrawals when they continue for months and years. Iatrogenic-induced PTSD is the result for many, that I know, for it happened to me.

Sometimes, one must stay away from all healthcare practitioners if one wants to heal and not become further harmed by well-intended doctors who do a lot of guessing in the field of medicine. Medicine has been described by many as an “art”, but I describe it as fancy footwork when the patient’s health record is written solely by the doctors about their patients behind their backs. I’d rather they include signed, informed consent forms that have the patient’s signature.

That will ensure that the patient’s back is protected, also.

~JLReoch

Report comment

Thank you, Robert, for the invaluable work you have done over several decades and for now producing this unassailable review. It should be the final nail in the coffin, but I won’t be surprised if the psychiatric zombie carries on.

Carolyn Quadrio

Report comment

Carolyn Quadrio, Robert Whitaker,

Carolyn, are you a doctor? A prescriber?

Report comment

Robert – Thanks for this essay: another powerfully reasoned critique about misleading promotion of falsehoods in psychiatric marketing and research.

I’ve posted a link to your article on the Volunteers In Psychotherapy Facebook page.

Report comment

We must greatly respect Robert Whitaker for his tireless work and ability to take the work of the academic community and throw it back in their faces.

I hope someone reads his entire articles. I myself can’t get through them.

But I have a comment – perhaps somewhat uninformed – regarding “genetic” causes of mental illnesses. I have understood from my teacher that many mental problems CAN appear to be transmitted through family lines. But the mechanism that accomplishes this apparent “genetic” transmission is not understood. The trauma-based theories have a clue, but most of them don’t include prenatal experiences.

Further, once science begins to understand that the mind is not a physical organ in the body, these biology-based theories will really begin to fall apart.

Report comment

Larry Cox, Robert Whitaker,

Conditioning, patterns of behaviours, et cetera.

If grandma wore pointy toed shoes and developed bunions, and her daughter wore pointy toed shoes and developed bunions, and her daughter (3rd generation) wore pointy toed shoes and developed bunions then bunions must be genetic ! Podiatry will find evidence for genetic bunions.

As for the mind and brain – make it all up, sell it to the public and write it in a book used for coding and insurance. Each update of the book can be genetic, as it carries forward from the past, and repeats the same. And when something new is added, it too can become genetic in the next update or edition.

Report comment

The NIH says that 1 in 5 cases of “schizophrenia” are, in reality, misdiagnosed cases of Toxoplasmosis gondii. This is an infection by a protozoa, a microorganism we humans typically contract from a cat that has caught it from a rat. The protozoa create cysts that can grow anywhere in the body and when they grow in the brain, as you can imagine, they cause the brain to malfunction, resulting in schizophrenia or psychosis. The NIH also says the herbal extract, artemisinin, kills these protozoa. You might assume psychiatrists would do a trial of artemisinin on ALL their schizophrenic or psychotic patients to try to cure 21% of their cases but you’d be wrong. Psychiatrists only know how to prescribe patented, synthetic drugs in an effort to suppress patients’ symptoms until they die. (And let’s not forget, curing a patient is also killing the golden goose that keeps on giving until it dies.) MY loved one became psychotic while our cat was sick. What (finally) cured him was homeopathy. He’s fine now. He has a job, pays taxes, and is 100% free of psychiatrists and their miserable drugs. Keep in mind, Toxoplasmosis is just one proven, physical cause of mental illness. There are others the Am Psych Ass’n is ignoring, too, so they can turn each patient into a lifelong “customer” of psychiatric goods (drugs) and services (talk therapy). There is NO law that says the APA must even try to cure a patient. The APA is a corporation that has 100% carte blanche to choose any approach they like, and what they like are profits. —Linda, author of “Goodbye, Quacks – Hello, Homeopathy!”

Report comment

Linda Santini, Robert Whitaker,

Anything that cannot be easily or routinely checked and or measured can be diagnosed as a mental disorder – encephalitis, aseptic meningitis, is ignored even when the same presenting symptoms are those as for any other brain inflammation. Toxic brain injury caused by psychiatric and other medications is downplayed, ignored, denied, and treated as something else –

For sure this is deliberate, though possibly unconscious, in order to protect against litigation for example.

Report comment

Dear Robert Whitaker,

Foolishly trusting the prescriber!

Family death threats led to talking with GP/psychologist who immediately prescribed psychiatric drugs and benzos. Prior to ingesting said drugs in good faith there were no NO psychiatric signs, symptoms. Nor did the doctor check any baseline health conditions for nutritional, anaemia, hormone, kidney et cetera.

After just a few months first episode psychosis upon stopping drugs. The wheel was set in motion for psychiatric history and several more psychosis episodes, regardless of how slowly tapered from drugs; as well as cascade prescribing for symptoms caused by each drug prescribed. Several involuntary stays in institutions where even upon voluntary admission, leaving is not an option unless approved. Twenty years of mistreatments, neglect, and losses of jobs, family, friends, neighbours, community ….

Is Big Pharma going to succeed in the biology of illnesses and diseases of the mind, brain ? It sure was highly successful with the medical model and mental disorders!

The word needs to be put out to not buy into this drug-fuelled propaganda. Enough already.

Please ring out louder and louder – maybe an other Big Book ?

Cascade prescribing ? Iatrogenic harms ?

Why would parents want to be so keen to drug their own child ? Why speed kills: never enough time to do the right thing ? What’s a death here or there: psychiatry’s unnatural attrition ?

Never ask your child for help: this type of child abuse is traumatic for the child ? Your mental illness is contagious; it spreads on your alleles ?

Good luck finding a partner, spouse: marrying bad genes ? Hmmm …. Catchy book titles – maybe

Report comment

American-style psychiatry cures no one because it isn’t designed to cure anyone, just bring in the highest possible profits. It’s such a scam. There is no law that says the APA must even try to cure a patient. The APA has 100% freedom to choose any approach they like so they have chosen what brings them and their business buddies, the drug companies, the highest profits. I recognized this back in 1996 and started doing my own research into the natural causes and cures of mental illness. Since then, I’ve found 2 approaches that recognize and correct the proven, underlying causes. Orthomolecular treatment restores one’s mental health biochemically. It’s natural and therefore un-patentable which means low profit. Homeopathy is also natural, un-patentable and brings in pennies in profit. It cures the cause of mental illness, gently, deeply, permanently, while the APA continues to fight against homeopathy and orthomolecular. These are both wonderful approaches—that work. – Linda, author of “Goodbye, Quacks – Hello, Homeopathy!”

Report comment