Editor’s Note:

This is part three of a three-part series.

When we consider that psychosis often results from the failure to experience healthy individuation (as discussed in Part Two), we can see that a kind of intrapsychic split has developed, where a person feels terribly torn between a longing for freedom and autonomy on one side, and a longing for love, belonging and nourishing connection on the other side. Or to consider this same dilemma from the perspective of fear rather than longing, we can say that a person feels terribly torn between a fear of loneliness and isolation on one side, and a fear of being oppressed or “losing oneself” within relationship on the other side. When we recognize this tension lying at the root of a person’s psychotic process, we find that it offers us some very useful guidance in supporting a person working with experiences that may otherwise seem so chaotic and unpredictable. In particular, what we find is being called for is supporting this person in experiencing both healthy autonomy and personal empowerment, and also healthy connection with others. To begin laying down an effective framework for how we may best be able to do this, let’s first briefly touch into the concept of parenting styles.

Towards an Effective Parenting Style

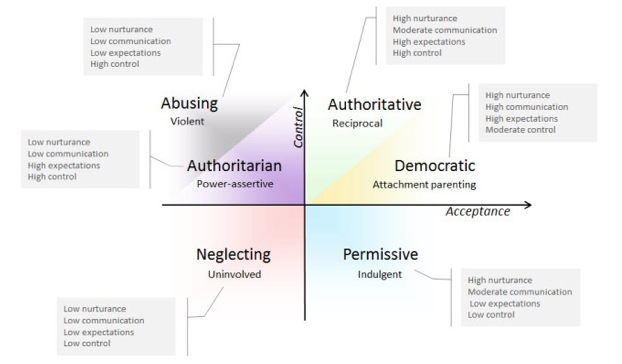

There has been a lot of theory and research on different parenting styles over the years, with some styles being seen as more problematic than others. One relatively simple framework that a lot of people resonate with makes a distinction between authoritarian, neglecting, permissive and authoritative parenting styles, and I think it’s helpful to consider these different styles from within the context of healthy autonomy and connection as presented within this article series (see Figure 1).

With authoritarian parenting, there is little collaboration or discussion with the child regarding the setting of limits, and these limits are strictly enforced typically with punishment. The child’s autonomy needs are generally oppressed, and while there may be genuine love and affection from the parent, communication is generally poor, leading to the child’s connection needs also generally not being adequately met.

With permissive and neglecting parenting styles, limits are generally not discussed or even set, let alone enforced. While it could be argued that their autonomy needs are being met, in actuality, because developing children need guidance in understanding their limits and developing self responsibility for the consequences of their actions, the kind of autonomy developed with these styles often consist of poor impulse control and poor self responsibility, which in turn limits the ability to develop healthy relationships with both self and others. Regarding healthy connection needs, a significant difference between neglecting and permissive parenting styles is that the permissive style generally includes more healthy connection—the child is treated like a “loved friend”—whereas there is very little nourishing connection with a neglecting parenting style, the child being treated essentially as a nuisance to be tolerated with minimal effort on the part of the parent(s).

With the authoritative (not authoritarian) parenting style, the emphasis is placed on setting clear reasonable limits, using as much warmth, collaboration and communication with the child as possible while setting and enforcing these limits. The child is then allowed essentially as much freedom and autonomy as possible within these limits. Considering this style from within the framework presented here, it’s easy to see that this particular style is likely to be the most effective style in supporting the child in resolving the autonomy/connection dialectic and ultimately achieving mature individuation. And indeed, extensive research has demonstrated that children raised with this particular style are most likely to develop satisfying and nourishing relationships with self and others (Baumrind, 1989; Furnham & Cheng, 2000; Galambos, 1992).

Two sub-categories of the authoritative parenting style that are helpful to consider are attachment parenting and democratic parenting. These can essentially be seen as simply a sequence of two stages following the same pattern of maximal warmth, communication and freedom held within clear and reasonable limits, with “attachment parenting” typically referring to practicing this within the communication constraints of infants and toddlers, and “democratic parenting” referring to the practice of increasing communication and collaboration with the child as she matures and develops increasing life experience and critical thinking skills. The nice thing about this approach is that not only does it maximally support the child in meeting her autonomy and connection needs, but it naturally follows the child’s developmental process culminating in healthy adult individuation. [A couple of useful books that offer guidance to parents in developing these types of parenting styles are No-Drama Discipline, by Dan Siegel and Tina Bryson (2015), and Hold On To Your Kids, by Gordon Neufeld and Gabor Mate (2014).

While the concept of implementing such a reasonable parenting style as a means to support a child in developing secure attachment styles and ultimately adult individuation may seem simple enough, many parents will recognize that the reality is often far more challenging. When raising a child, we find that we typically encounter the unresolved developmental wounds of our own past, which can then result in powerful emotions that “hijack” us and compel us to behave in ways towards our children that we may later regret. One way to think of this is that when raising children, our own insecure/unresolved attachment issues show up and are easily transmitted to our children. The research suggests that insecure attachment styles are very often transmitted this way from one generation to the next, in spite of what may be the parents’ best intentions (Karen, 1994; Siegel & Hartzell, 2003).

Fortunately, the research also suggests that it’s never too late for any of us to work on increasing the security of our own attachment styles both in relationship to our self and with others, especially by utilizing the practices of mindfulness, creating a coherent narrative of our own lives, and seeking skilled relationship support (Siegel & Hartzell, 2003). And the research also suggests that parents who have been able to do this personal relational repair work, regardless of how troubled their own childhood may have been, are far more likely to raise children with secure attachment styles and the many benefits of this, as we’ve been discussing (Karen, 1994; Siegel & Hartzell, 2003).

So it’s all well and good to learn about effective parenting styles, and to try one’s best to implement them from the very beginning, but what do we do once we find ourselves in the midst of a crisis with a child/adolescent/young adult exhibiting psychotic or other extreme behaviors, and/or a family system that has already become destructive and out of control? The following are some of the most common problematic dynamics the recovery research suggests are found within such family systems, along with some suggestions for transforming these patterns from problematic to beneficial, or in other words, from vicious cycles into victorious cycles.

From “Power Over” to “Power With”

As implied in the above discussion on effective parenting styles, it appears that developing a “power with” relationship with one’s child, rather than a “power over” relationship, is key. So often in family systems in which a child becomes diagnosed with a psychotic disorder, a strong “power over” dynamic has developed, typically between one or more parents and the child, though we can also find this particular dynamic within other aspects of the family system, such as between siblings.

Even if this particular dynamic was not prevalent initially, once the child is deemed “mentally ill,” the individuation fears as discussed above can become exacerbated, leading to increasing tension within the autonomy/connection dialectic for the child and hindering even further her movement towards individuation. In this case, out of natural concern, the parent may well become increasingly critical, demanding, overprotective, etc., further undermining the child’s autonomy/connection needs; and the child is likely to experience increasing self doubt, self fear, etc., increasing her ambivalence of moving towards healthy individuation. This situation is likely to further increase the “power over” dynamic at play, even further interfering with the child’s individuation process, and we find that a kind of positive (self reinforcing) feedback loop (i.e., “vicious circle”) develops, in which the system can become very entrenched within this particular dynamic, with the child unable to go any further towards individuation and remaining hyper-dependent upon the parents indefinitely.

Unfortunately, the mainstream mental health care system often further exacerbates the situation, by adding its own “power over” structure to the already existing “power over” dynamic occurring within the family. It does this by generally insisting that the youth “accepts” that they have a brain disease, insisting that they remain “compliant” with psychiatric drugging, and generally behaving in a way that is likely to exacerbate whatever trauma the youth has already experienced and even further encouraging the “power over” dynamics within the family (see my article here for more about these and similar problems within the mainstream mental health care system).

Breaking this vicious cycle requires first a willingness by all parties to recognize that this is occurring, followed by a concerted effort to gently make the transition from “power over” to “power with.” This includes the need for all family members to resist any tendencies to make demands of each other, and to instead make clear, doable requests, with a willingness to hear “no.” It also includes the need for each person to set personal limits and boundaries as would be done within any other healthy relationships, and to do their best to honor those set by others. In other words, if a person is behaving in a way that is directly harmful to us or our loved ones, we do need to set some personal limits and do our best to minimize that harm, which may entail attempting further communication with the person, or if this fails, then seeking external support or even limiting contact with the person, if necessary.

From Mystification to Transparency

The recovery research also suggests that transparency within our communication and our general self expression is also very important. Without doubt, one of the main factors that has made the Open Dialogue approach and other similar family systems approaches so effective is that they facilitate transparency, which we can define as first developing self connection (connecting with one’s own feelings and needs associated with a particular situation), and then expressing this to the relevant other openly and honestly. As discussed earlier, Bateson’s and Laing’s work in this area, with their concepts of “double binds” and “mystification,” offer compelling theories as to how the lack of transparency, especially between the parents and the child, can result in the child experiencing overwhelming confusion and distress, even to the point of ultimately developing a psychotic condition.

To be more specific, being transparent essentially means finding the courage to express our concerns, frustrations, fears, etc. directly to the relevant person—to clearly state what it is about the others’ behavior that is so distressing to us, and then depending upon what feels most appropriate, to either do some personal work on developing more tolerance for that behavior, or to open up dialogue with this person about what changes could be made to make the situation more workable for all involved. The other important piece to this is resisting the temptation to complain to a third party about a person’s behavior, and to instead find the courage to discuss the problem directly with that person. Murray Bowen refers to this—the tendency to form an alliance with one person against another—as triangulation, and his research has demonstrated it to be a particularly destructive relational pattern within families and other social systems (Bowen, 1993).

From Scapegoat to Canary

A common pattern we find within many social systems when they’re not functioning well is scapegoating, the tendency of the majority of members to attribute the brunt of the responsibility for the dysfunction within the system to a particular minority. We see this within the broader social systems in which minority members are scapegoated, in smaller social systems such as schools in which children who are perceived as “weak,” “nerdy,” or otherwise “weird” are bullied, and within family systems in which one member is perceived to be the “problem child,” or what family systems therapists often refer to as the “identified patient.”

It’s important to recognize, however, that this tendency is usually misguided and often very destructive, not only to the one who is scapegoated, but to the overall health of the family system, in that scapegoating may buy some security in the short term, but leaves the family system vulnerable to collapse in the likely event that the strategy eventually fails. It is for this reason that scapegoating can become so entrenched within a dysfunctional family system, with all members, including the one scapegoated, often striving to maintain this status quo in order to maintain the survival of the family system (although the family members are often not consciously aware that they are doing so). Unfortunately, this problem can become even further exacerbated by a mainstream mental health care system that feeds this dynamic by generally being more than happy to diagnose and “treat” the identified patient, with many professionals sincerely believing that they have the expertise to declare that there is indeed something broken or diseased about the brains of such individuals, in spite of extensive evidence to the contrary (see this article or Rethinking Madness for more a more thorough discussion about this).

In order to pull ourselves out of such a problematic family dynamic, it helps to recognize that the “identified patient” is often merely particularly sensitive to the dysfunction within the family system, and therefore is vulnerable to acting as a kind of channel for this dysfunction, personally acting it out in a way that is likely to land her with the diagnosis of a “mental illness.” Therefore, it’s often much more helpful and accurate to see the “identified patient” as a “canary in the coal mine” rather than “mentally ill,” in that she is simply the first to perceive and openly demonstrate the toxicity within her environment.

From multiple monologues to authentic dialogue. When we shift our perspective to see “psychosis” occurring within an individual as actually most likely being indicative of a problem occurring within the larger family and social system, then we recognize that it is only by honoring everyone’s unique perspective that we are able to acquire a view broad enough to lead to the resolution of whatever is occurring within that system. In order to do this, we find that we must face a somewhat daunting but not impossible task: To practice open and authentic dialogue with the others in the system, which requires a willingness to alternate between (a) honest self connection and authentic self expression, and (b) temporarily setting aside our own assumptions, beliefs, feelings, etc., so that we can listen to the others in a receptive and empathetic way.

When we are distressed, it is a natural tendency to become so inflexible in our own perspective and/or so absorbed in our desire to express this to the other, that we then are simply unavailable to genuinely listen to and digest the perspective of the other. This results in communication consisting of multiple monologues (i.e., multiple individuals essentially expressing themselves to “brick walls”) rather than an authentic dialogue. Yet, in order for the broken system to change in any fundamental way, the different members of that system must each be able to bring their voices to the table and be genuinely heard by the others so that a new and hopefully more harmonious and sustainable relational dynamic may unfold. I have found that a particularly simple and effective approach to such communication is Nonviolent Communication [NVC], developed by Marshall Rosenberg, student of the pioneering humanistic psychologist, Carl Rogers.

Secure Attachment as a Buffer Against Bullying and Other Adverse Childhood Experiences

As discussed earlier, we are all “hardwired” to strive to develop secure attachments with one or more primary caretakers from birth, and recall that such a secure attachment involves the experiential knowledge that we are deeply loved for who we are—that both our primary connection needs and our primary autonomy needs are securely held and supported. And when children and adolescents are unable to develop these with their parents, they naturally direct these attachment-forming instincts toward their peers. But since other children and adolescents are generally not able to take on the role of caring, mature caretakers for each other, what typically results is a situation in which the “blind are leading the blind,” or worse yet, the immature are leading the immature; and this in turn can set the stage for an absolutely devastating blow to occur at a very deep level when the youth is exposed to the experience of being harshly rejected by those with whom she or he is so desperately trying to attach. [See Hold on to Your Kids by Neufeld & Mate (2014) for a much more thorough discussion about these issues.]

Considering the situation from this perspective, it actually makes a lot of sense that bullying and peer rejection have been so well established to be a significant risk factor for youth developing psychotic disorders. It’s easy to see that when youth try to get their primary attachment needs met from other immature youth, this sets the stage for a catastrophic blow to one’s ability to sustain a tolerable experience with regard to the autonomy/connection dialectic. But fortunately, it has also been well established that a secure attachment with an adult acts as a powerful buffer against the harm caused by such peer bullying and rejection.

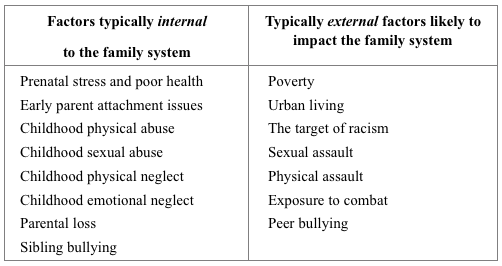

One particularly striking study involved 90,000 adolescents from 80 different communities throughout the United States, and found that those who were securely attached to at least one parent were much less likely to exhibit the behaviors typically associated with problematic peer attachment issues—drug and alcohol dependency, attempted suicide, engaging in violent behavior, and risky sexual activity (Resnick et al., 1997). This study didn’t include psychosis as an outcome variable; however, given the established correlations demonstrated between poor attachment with parents, bullying and psychosis, I think it’s safe to connect these dots and recognize that secure attachment with a parent almost certainly acts as a direct buffer against the possibility of bullying and peer rejection precipitating psychosis. Furthermore, following a similar line of reasoning, I think we can safely say that secure attachment with a parent is likely to act as a buffer against most of the other psychosis risk factors mentioned in Table 1 below (explained in more detail in Part One of this article series).

From Blame to Shared Responsibility

As discussed earlier, it’s a very delicate matter to suggest that, in many cases, the parents of a youth who develops a psychotic disorder may have played some role in that occurring. This suggestion has resulted in a polarization within the field in which on one extreme we find an inappropriate degree of blame being placed onto the parents, especially the mothers, of all youth who develop a psychotic condition; and on the other extreme, those who suggest that family dynamics often do contribute to the development of psychotic conditions are themselves vilified.

To give one example of the first extreme, a term often used throughout the last decades of the 20th century is “schizophrenogenic mother,” a term coined by psychiatrist Frieda Fromm-Reichmann in 1948 to highlight her belief that certain mothering/parenting styles are causally linked to the development of “schizophrenia.” Regardless of the intention of Fromm-Reichman and others who have found utility in this term, it can easily be interpreted as implying a kind of black-and-white blaming and shaming of parents whose children develop a psychotic condition, which I feel is likely to only reinforce the problem. The risk in the use of this kind of language is that it can understandably lead to many parents becoming defensive, which may then result in even further disconnection and disharmony within what is likely already quite a troubled family system.

On the other extreme, those who suggest that there may be something about family dynamics that can contribute to a child’s psychosis are sometimes referred to derogatorily as “mother blamers,” a term I feel is equally problematic, in that this term typically represents a complete deflection of any parental responsibility in cases where some responsibility by the parent(s) may indeed be warranted—if not direct responsibility for the onset of the child’s psychotic condition, then at least a certain degree of responsibility with regard to supporting their child through the recovery process.

Between the extremes of blaming and shaming parents on the one hand, and denying any responsibility whatsoever of the parent/child relationship on the other hand, I believe there is a middle path that we can follow that will allow us to have a fruitful exploration of this issue while not losing sight of the humanity of all involved. Very often, parents do love their children very much, and do strive to do the best that they can as parents, and yet their behavior and parenting style still unwittingly contribute to their child developing such a distressing condition. In many such cases, the parents were themselves raised as children in a similarly problematic environment, and are merely passing along what they have learned. Such problematic dynamics can become profoundly entrenched within a family system, often lasting for many generations and making it very difficult for the parents of any one generation to fully extract themselves from them. Furthermore, it must be acknowledged that many parents in the world today are forced to try to survive in the life-crushing conditions of poverty, isolation and/or political oppression, which in turn simply leaves parents with few remaining resources with which to nourish their children. Indeed, the literature is robust with evidence that poverty, discrimination and other forms of political oppression are highly correlated with the development of psychosis (Read, 2004).

So I think that rather than resorting to “parent blaming” and suggesting that parents in these cases must have malevolent intentions, it’s important to recognize that in probably the majority of these cases, the parents are simply ignorant of the serious harm that their behavior is causing, and/or they are merely passing down inter-generational trauma or relational dynamics that they themselves have inherited from their own parents and/or a dysfunctional society. Rather, what is likely to be more helpful than blame is to invite an attitude of open curiosity about what problematic family dynamics may be involved in the distress, and to encourage an attitude of shared responsibility among the members of the family and the broader social system with regard to repairing any harm done and transitioning to a more harmonious system.

Another point that needs to be stated here is that, as discussed above, the research is quite clear that many different factors may contribute to a person developing psychosis. Yes, relational factors, and especially childhood relational factors, do seem to be at play in probably the majority of cases of psychosis, at least those that have been thoroughly explored; but we are complex organisms, whose wellbeing is based on a multiplicity of factors occurring within multiple domains—physiological, psychological, social, environmental, spiritual, existential, etc.—and if we consider that psychosis is often a desperate strategy to cope with otherwise overwhelming experience, it becomes clear that multiple factors and experiential domains often converge to create such overwhelming conditions. So, in many cases, pointing towards any one single factor as the cause of a person’s psychosis is far too simplistic.

What this understanding implies, then, is that if we want to offer genuine support to people struggling with overwhelming distress, then all members of a particular family system and even the broader social systems need to acknowledge some degree of shared responsibility and to act from that place. However, along with this recognition needs to come the recognition that different members within these social systems do hold different degrees of power, and greater power naturally entails greater responsibility. Since it is the parents who typically hold the most power within the family system, it’s important that they acknowledge the greater responsibility that goes along with this. The same applies to the broader social systems within which we live, in that certain members hold greater power and influence—especially those who are white, male, relatively wealthy, and those who hold certain professional roles, with health professionals having a particularly high degree of power within the context discussed here. Along with this greater power comes the potential to cause relatively greater harm or benefit, a fact that can be particularly destructive if not consciously acknowledged and carefully held by these more privileged members.

Distancing When Unable to Repair

Soteria-style homes, The Family Care Foundation, peer respites, and other similar methods have demonstrated that when repair of a particular family system is not working for whatever reason, moving into a healthier environment can be very beneficial for a person’s recovery. Bowen’s research (1960) has demonstrated that even moving into an environment that is not so healthy (such as an inpatient ward of a hospital) can have limited benefits, depending of course on just how harmful the individual’s family system has been. Of course, most hospital environments, and unfortunately most mainstream residential homes, are themselves antithetical to a person’s recovery process when considered from the perspective presented here, in that they are typically highly oppressive and don’t particularly convey the message that “you are loved, accepted and valued for who you are.”

It’s unfortunate that in spite of the very hopeful outcomes demonstrated by the Soteria-style homes that were developed in the 70’s, they remain extremely rare and therefore inaccessible for most people. However, there are signs that the tide is turning, as new Soteria-style homes and other similar kinds of residences are being established, and the peer and peer respite movement is gaining steam. With increasing awareness of the tremendous benefits of such residences for individuals, families and communities, hopefully there will come a time when every community will have a “madness sanctuary” to offer much needed compassionate respite to those in crisis. [See my resource list here for some of the organizations and services that are available.]

Conclusions

As we draw near to the end of this journey through the research on the links between family dynamics, human development and psychosis, we can reflect on what we have learned and wrap up a few conclusions to take away with us:

- Certain traumatic incidents, particularly many of those listed in Table 1, can directly or indirectly lead to a psychotic crisis.

- We all share certain core needs and existential and relational dilemmas (see Figure 1 in Part Two of this article series), and when these are chronically unmet and/or unresolved, as can result from the traumatic incidents listed in Table 1, we may experience enough overwhelm that our organism initiates a psychotic response as a desperate strategy to tolerate what would otherwise be intolerable.

- It’s likely that we all have a tipping point, a point at which we become overwhelmed to the point of initiating a psychotic response, although personal vulnerability to this may differ substantially from one individual to another.

- Fortunately, there are a number of strategies we can implement to reduce the likelihood of ourselves or a loved one going down the path of psychosis, or to support recovery once someone has already gone down this path. What is likely to be of particular benefit is transforming problematic family and relational dynamics into more harmonious ones, including especially:

- Striving to develop parenting styles with high degrees of collaboration, communication and nourishing connection.

- As parents, developing and maintaining secure attachment with our children through adolescence, and then supporting them in transitioning towards increasing autonomy as developmentally appropriate.

- Developing “power with” rather than “power over” relationships.

- Working towards maximal transparency (rather than mystification or triangulation) and authentic dialogue (rather than multiple monologues) within our communication.

- Letting go of blame and scapegoating, and working towards personal accountability and shared responsibility.

- Recognizing the benefit of distancing from unhealthy family relationships and pursuing alternative nourishing relationships when we are unable to repair the family relationships.

Finally, it’s important to recognize that that we are profoundly social beings living not as isolated individuals but as integral members of interdependent social systems—our nuclear family system, and the broader social systems of extended family, peers, our community and the broader society. Therefore, psychosis and other forms of human distress often deemed “mental illness” are best seen not so much as something intrinsically “wrong” or “diseased” within the particular individual who is most exhibiting that distress, but rather as systemic problems that are merely being channeled through this individual. Furthermore, certain members of these social systems clearly hold more power than others; and those who hold the greatest power, such as parents and health professionals, also hold the greatest potential to produce both harm and benefit, therefore making it essential that the greater burden of responsibility that goes along with this greater power is acknowledged and carefully held. In spite of these power differentials, however, we must not forget that all members of a particular social system hold some degree of power—with every action we take, every word we utter, every vote we make, and every dollar we spend, each and every one of us plays a role in perpetually co-creating the social systems in which we live. So it’s up to each of us to ask ourselves what kind of world we want to aspire towards—a world filled with fragmentation, blame and disconnection, or a world of open dialogue, shared responsibility and nourishing support and connection.

* * * * *

References:

(for all three parts of the article)

Bakhtin, M. (1984). Problems of Dostojevskij’s poetics. Theory and history of literature: Vol. 8. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Bateson, G., D. Jackson, D., Haley, J., & Weakland, J. (1956). Toward a Theory of Schizophrenia. Behavioural Science 1, pp. 251-54.

Baumrind, D. (1989). Rearing competent children. In W. Damon (Ed.), Child development Today and Tomorrow. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Berry, K., Barrowclough, C., & Wearden, A. (2007). A review of the role of attachment style in psychosis: Unexplored issues and questions for further research. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(4):458-475.

Bola, J., & Mosher, L. (2003). Treatment of acute psychosis without neuroleptics: Two-year outcomes from the Soteria project. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191(4), 219-229. doi:10.1097/00005053-200304000-00002

Bowen, M. (1960) A family concept of schizophrenia IN D.D. Jackson (Ed.) The Etiology of Schizophenia. New York: Basic Books.

Bowen, M. (1993). Family therapy in clinical practice. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss, 3 vols. London: Hogarth, 75.

Brown, G.W., Bone, M., Palison, B. & Wing, J.K. (1966) Schizophrenia and Social Care. London: OUP.

Fromm-Reichmann, F. (1948) Notes on the development of treatment of schizophrenics by psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. Psychiatry, 11, 263-273.

Furnham, A., & Cheng, H. (2000). Perceived parental behavior, self-esteem, and happiness.Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 34(10, 463-470.

Galambos, . L. (1992). Parent-adolescent relations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1, 146-149.

Goldstein, M. The UCLA High-Risk Project. Schizophrenia Bulletin 1987; 13(3):505-514.

Greenberg. J. (1964). I never promised you a rose garden. Chicago; Signet.

Janssen I, Krabbendam L, Bak M, Hanssen M, Vollebergh W, de Graaf R, et al. Childhood abuse as a risk factor for psychotic experiences. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2004;109(1):38-45.

Karen, R. K. (1994). Becoming attached: First relationships and how they shape our capacity to love. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Laing, R.D. (1960) The divided self: An existential study in sanity and madness. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Laing, R.D. and Esterson, A. (1964) Sanity, madness and the family. London: Penguin Books.

Laing, R.D. (1967). The politics of experience. New York: Pantheon Books.

Miklowitz, J.P. (1985) Family interactions and illness outcomes in bipolar and schizophrenic patients. Unpublished PhD thesis, UCLA.

Mosher, L. R. (1999). Soteria and other alternatives to acute psychiatric hospitalization: A personal and professional review. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187, 142-149.

Napier, A.Y. & Whitaker, C.A. (1978; 1988). The Family Crucible. New York: Harper & Row.

Neufeld, G., & Mate, G. (2014). Hold on to your kids: Why parents need to matter more than peers. New York: Ballantine Books.

Norton, J. P. (1982) Expressed Emotion, affective style, voice tone and communication deviance as predictors of offspring schizophrenic spectrum disorders. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, UCLA.

Read, J. (2004). Poverty, ethnicity and gender. In J. Read, L. R. Mosher, & R. P. Bentall, (Eds.), Models of madness: Psychological, social and biological approaches to schizophrenia(pp. 161-194). New York: Routledge.

Read, J., Fink, P., Rudegeair, T., Felitti, V., & Whitfield, C. (2008). Child maltreatment and psychosis: a return to a genuinely integrated bio-psycho-social model. Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses, 2(3), 235-254.

Read, J., & Gumley, A. (2008). Can attachment theory help explain the relationship between childhood adversity and psychosis? Attachment—New Directions in Psychotherapy and Relational Psychoanalysis, 2(1):1-35.

Resnick, M. D., Bearman, P. S., Blum, R. W., Bauman, K. E., Harris, K. M., Jones, J., … & Udry, J. R. (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm: findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Jama, 278(10), 823-832.

Seikkula, J., Aaltonen, J., Alakare, B., Haarakangas, K., Keränen, J., & Lehtinen, K. (2006).Five-year experience of first-episode nonaffective psychosis in open-dialogue approach: Treatment principles, follow-up outcomes, and two case studies. Psychotherapy Research,16(2), 214-228. doi: 10.1080/10503300500268490.

Seikkula, J., & Olson, M. E. (2003). The open dialogue approach to acute psychosis: Its poetics and micropolitics. Family process, 42(3), 403-418.

Selvini-Palazzoli, M., Boscolo, L., Cecchin, G., (1978). Paradox and counterparadox. New York: Jason Aronson.

Shelvin M, Houstin J, Dorahy M, Adamson G. Cumulative traumas and psychosis: an analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey and the British Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Schizophr Bull 2008;34(1):193-99.

Siegel, D., & Hartzell, M. (2003). Parenting from the inside out: How a deeper self-understanding can help you raise children who thrive. New York: Tarcher/Penguin.

Siegel, D., & Payne, T. (2014). No-drama discipline: The whole-brain way to calm the chaos and nurture your child’s developing mind. London: Scribe.

Whitaker, R. (2010). Anatomy of an epidemic: Magic bullets, psychiatric drugs, and the astonishing rise of mental illness in America. New York, NY: Crown Publishers.

Williams, P. (2011). A multiple-case study exploring personal paradigm shifts throughout the psychotic process, from onset to full recovery. (Doctoral dissertation, Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center, 2011). Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi.com/34/54/3454336.html

Williams, P. (2012). Rethinking madness: Towards a paradigm shift in our understanding and treatment of psychosis. San Francisco: Sky’s Edge Publishing.

Wynne, L.C., Ryckoff, I.M., Day, J. & Hirsch, S.I. (1958) Pseudomutuality in the family relations of schizophrenics. Psychiatry, 21: 205-220.

Hi Paris, I’ve been enjoying your series and it’s been extremely thought-provoking while shining a light on vital matters concerning our mental health, with respect to family relationships.

However, part 3 I’m finding to be more academic than truth-ringing on a practical level. While I can see how your model perhaps reflects some general patterns, families are as unique as individuals. Plus, there is something about this installment that reads as a reflection of a specific culture (middle class white American), whereas families of different cultures would have extremely varying points of view, patterns of communication, expectations, judgments, acculturation processes, etc. Being the son of immigrant parents and growing up in the deep South had a huge impact on my perception of myself and my relationship to my community.

Sometimes communication by language is just futile, and it’s important for a person to find their own way in order to feel whole, healthy, and empowered. Solitude is a necessary step for true freedom, to define ourselves outside of any human mirroring, and just know ourselves as a reflection of our own experiences, and what we manifest on a daily basis. That’s a true reflection of our spiritual nature, and where healthy, self-nurturing individuation can actually occur.

We are, indeed, social, but we are also in relationship with ourselves, and this needs to be developed to avoid chronic dependence. There is balance to be achieved, here.

Sometimes, there is nothing to reconcile, and it’s just a matter of moving on, to create a new set of experiences, and a life away from the shackles of the illusion of emotional debt, which can be very manipulative and controlling in a family system. Being made to feel guilty for individuating is not terribly uncommon, and indeed, it can fester into chronic inner conflict and dissociation.

What we seek, I believe, are examples of personal freedom and inner peace, because from there, we have unlimited power of creativity. Those with whom we authentically resonate will more than likely NOT be our family of origin, so our communities will look different than our initial family dynamic. To me, that is a step forward. How we get there will be a wildly different journey for each one of us. And how our families contribute to our journeys is just as wildly unique.

Thank you so much again for providing such food for thought, really good stuff.

Report comment

Alex, there are also many commonalities across families, including especially what children need to be grow up emotionally healthy – a certain degree of close, supportive, loving relationships (vulnerability and idealizing needs, in Heinz Kohut’s language) as well as a certain degree of freedom to be independent and develop their own activities of interests (autonomy and need for mirroring). Families can be unique – and you are right that they are – and yet still they can have much in common in terms of the core emotional needs that the children within them seek.

Report comment

Well said, BPDTransformation.

Best regards,

Paris Williams

Report comment

I don’t disagree with any of this, BPD, but my point is that this balance will be and look different in every single case, as per not only our individual nature, but also a network of unique circumstances, mostly converging into how we walk our talk, regardless of individual and cultural differences. What we learn in our families is either in synch or not with our nature, and when it is not, that will change the landscape of our development into maturity.

Our well-being is determined by how in synch we are with ourselves, because when we are, we will know others of resonance, family member or not. But if we go by how others perceive or feel about us, then we are distracted from our true selves, and give others power over us.

To me, learning our personal truth above and beyond family or community norms is a determining factor for balance and well-being as transition into adulthood. At what point do we take the reigns ourselves, and stop depending on family–or anyone–to guide us through life?

Bottom line is that in the end, we are our own guides and healers. Family is what it is, and that’s different for everyone–including for people within the same family.

Report comment

And again, my flag for illusory projections is when we turn to academics for our truth. I believe our own personal experiences and the observations and conclusions thereof, trump impersonal and generalized research. We are our own beings, with our own truth to either follow or not. Academic research can either support our individual truth or not, but it can never dictate it. I think that’s where we err, when we look to others for our own truth, rather than looking within ourselves, which is where all the answers are to begin with.

Our relationship to our families are only personal, subjective, and intimate, each and every one of us unique in this regard. When we walk our talk, we discover the truth of our own experience, without judgment. We are all the authority of our own experiences, solely, and I firmly believe the buck stops there.

Report comment

Hi Alex,

I’m glad to hear you’ve generally been enjoying this series. I think you have an important point that there can be major differences between families and cultures; however, (as BPDTransformation says below), I do believe that there are a few key universals — particularly those I mentioned here (and summarized in the Conclusion). Especially that families represent a form of social system, and that as long as the family is living and surviving as such a system, distress occurring within one individual cannot be cleanly separated out from the family system as a whole–hence my belief in the universality of the principle of such distress as often being indicative of a “canary in a troubled coal mine” and of the principle of shared responsibility. Regarding transparent communication, I believe thgat we can see communication (whether verbal or nonverbal) as the fundamental links between the different members of the system, and that this applies among all social systems (indeed, all living systems period, although “communication” may manifest in very different ways in different kinds of living systerms). So when communication is distorted or blocked, I think it’s generally safe to say that the system as a whole is likely to suffer. Regarding attachment, it’s generally understood that all humans (regardless of culture) are “hardwired” as infants to strive towards secure attachment with one or more caretakers; and that an inability to do can lead to profound distress with long lasting implications for the wellbeing of that person. Finally, we generally know that in living/social systems, if each member is empowered (as opposed to oppressed), then we find a greater net total of power within the system that may be harnessed to maintain the survival and health of the system as a whole; and that mutual empowerment is far more likely to lead to harmonious functioning than oppression and rebellion.

I think what you’re emphasizing here, Alex, is the final principle I mentioned “distancing when unable to repair.” I agree that this is a very important principle not to lose sight of. Repair with those in our social network is ideal, but sometimes not possible, in which case, we may have to resort to the difficult work of repairing from those toxic relationships and developing a healthier social system. Indeed, this was the case with many of the participants of my own research, who felt they had to break away from such unhealthy relationships altogether in order to “recover” from their overwhelming extreme state of mind. This “breaking away” naturally occurs anyway to some extent as we individuate from our parents, but certainly the degree of harmony of the system we’re individuating from can make a huge difference in how smoothly this process will go, and to which extent we’re able to maintain supportive relations with our parents and nuclear family members.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts,

Paris Williams

Report comment

What I’m intending to emphasize here is that a family system can have certain values that do not apply to some of its members. Our spirits function as they do, each one of us unique in our unfolding and development. Our families are reflections of what we need to work on, they mirror our shadow, as well as our light.

When only one member takes on and lives by different core values than what the family culture dictates (by actions and implications of behavior), then that is when stigmatizing and marginalizing scapegoating can happen (interpreted as rejection, alienation, abandonment, etc.).

Not always, perhaps–sometimes a family system is open to evolving and taking their cue from a growth-oriented perspective, which to me, indicates unconditional love–which I think is pretty rare these days, to be honest. But in any event, that would be part of the value system by which it operates, simply from habit of beliefs.

So when an individual’s values and ways of being are judged by the family, simply for reasons having to do with control due to fear of someone going ‘outside the box,’ (fear because it tests the environment), then the dissident member of that system can internalize all sorts of negative beliefs, feelings, and energy–e.g., guilt, resentment, feeling disconnected and alone, etc.

When negative voices come in unison from a group, it can be extremely challenging for that person, to the point of trauma, especially if there had been emotional enmeshment, which of course with families, is way more than likely the case.

I think this is where standing in one’s truth is empowering, healing, and groundbreaking. In general, systems fight hard to stay status quo, unconsciously. When one person challenges the norms of that system (starting with family), that’s where everyone’s true colors come out, and members of that system are faced with discerning–and accepting humbly–what is in their control vs. what is not in their control, in addition to being faced with choosing how to respond when a member of the family challenges the system.

In the end, people cannot be controlled, we all have free will, so let the chips land where they may. These will be our families of resonance, regardless of our families of origin. These can be a bit of an illusion, when we consider the most powerful spiritual nature of our reality.

Report comment

Really, I guess what I’m looking at is when families take on cult-like characteristics, which I actually feel is pretty common. When one goes against the grain, a mass projection can occur where everyone swoops down to shame that person, in an attempt to keep the system status quo (and usually, the secrets, secret). I think it’s a fascinating phenomenon to witness, and way more common than not. That’s the product of living in a fear-based and stigmatizing/scapegoating society.

To change or not to change? That is the question…

Report comment

Paris: Your articles on family dynamics do ring as an element of truth to me. I was civily committed in 1989. I grew up in a violent household, and in 1989 I was sharing a household with five other social activist-sort of like a surrogate family. As such, I agree that my actions, whether correctly termed as irrational or self-defeating, would have better seen through the relationships with my housemates and the overall context of my life, than through biological psychiatry.

Report comment

Hi Chrisreed,

Thanks for sharing a bit about what sounds like a difficult time for you. I’m glad to hear you found that this article resonates for you. I think you also bring up an important point that such dysfunction and “canary in the coal mine” response by a sensitive member of the system can occur in all kinds of different social systems–not just within nuclear families–though I think that problems occurring within our most primary social system (i.e., our nuclear family) can predispose us to becoming more easily overwhelmed within our later social relations.

Best regards,

Paris Williams

Report comment

Paris,thanks for this I enjoyed reading your bibliography as well – important names there. Once upon a time and far way there were Social Workers and others that saw the dance of the family is beautiful shock and awe. Many of the names have been forgotten even I have forgotten some of them. One actual MD Pscy writer actually wrote a beautiful piece on the spiral dance between and infant and it’s mother. Selma Fraiberg wrote an amazing article on mothers who were unable to attach to their infants due to their own childhood. None of these or other author folks made any claim that these parents were “bad”. Many saw them as trying their utmost to do their best without having tools and knowledge and experience that other people were gifted by pure luck of the draw. And then slowly ever so slowly even the good voices – the one s that existed with the bad that were always there – that so many on this site have had the tragic gift to interact with – the good voices got rubbed out by multiple factors – follow the money!

Alex you are on target as always as well. So many many layers that need to be opened up and looked upon. It will take years to undig them all. Just the idea that microbes and microbes in the gut via one of my children affect everything in the body! How to discover and delineate that mystery with the fact there is more serotonin in the gut then brain. Go figure? How does the alternative type of therapies actually help families? Can there be family yoga centers in urban areas free of charge? Can there be meditation rooms set in place? Can there be places of interaction for families and folks rural, urban, and suburban? Can we learn to talk with each other not only in families but with all of us?

All of these things will help reduce the occurrence of nonchosen altered mind states. And for those that are called to go through a journey like the old druid poets and shamans let there be schools!

Again thanks.

Report comment

Hi CatNight,

I appreciate and resonate with everything you’re saying here–I think you have a wonderful way with words.

I also share a longing for these visions of a more harmonious world–in which support for individual, family, mind, body, communication, etc., are freely provided to everyone. I’m currently brainstorming setting up such a “holistic wellbeing” centre in my own community (though it hasn’t gotten off the ground yet):

http://cncl.org.nz/about/4588292758

In solidarity,

Paris Williams

Report comment

Hi Paris,

This is another excellent essay; I like the focus on actual relational strategies for helping a psychotic person become well.

There are a few other authors you may want to add to your lexicon if you haven’t already:

– Otto Kernberg and the neo-Kleinian object relations developmental viewpoint. The fears you describe according to them would be fear of engulfment/fusion (too close to others), and fear of abandonment/falling into a black hole (too far from others). There are other writers in this group like James Masterson, Gerald Adler, Peter Giovacchini, James Grotstein, and Donald Rinsley plus their many trainees.

The way Kernberg (based on Fairbairn, Jacobsen and Klein) conceptualized emotional development as requiring a buildup of all-good self and other images that becomes stronger than and integrates with the all-bad set of images is to me very useful. In this model psychosis is a regression or a non-emergence (developmental arrest) from the earliest developmental stage in which all-bad self and other images are dominant over all-good images, and at which fusion (extreme confusion and merging of self-qualities with other qualities, i.e. failure to differentiate one’s self from other representations) predominates more than splitting. Vamik Volkan wrote about these processes very well, as did Kernberg. I have tried to give a rough overview of the developmental continuum here, in a slightly different way to the other article I shared with you:

https://bpdtransformation.wordpress.com/2015/03/19/23-the-borderline-narcissistic-continuum-a-better-approach-to-understanding-diagnosis/

– Another great writer is Heinz Kohut and his self-psychological writing about the need for idealizing-vulnerability (what you describe as the need for secure attachment and emotional closeness) and the need for mirroring-autonomy (what you describe as the need for independence). There’s a large group of self psychologists following in his footsteps that now write about these core needs.

– My favorite writer on psychosis is Lawrence Hedges and his book the Organizing Experience. If you haven’t read it check it out! His approach is quite similar to yours. He reconceptualizes psychosis or schizophrenia as “organizing experience” in which a person is trying to organize their perceptions or need for contact in the face of a world or relationship environment that has not met or has traumatically rejected their needs. He renames therapist and patient as speaker and listener (Listening Perspectives). He gives fascinating case studies and also analyzes how psychosis and the organizing experience appear in literature like Franz Kafka. You can get it for $5 used:

http://www.amazon.com/Working-Organizing-Experience-Transforming-Psychotic/dp/1568212550

I did not know about all the writers you mention, but the ideas immediately make sense because they are exactly the same developmental relational ideas as in the authors mentioned above.

Your point about the mainstream mental health system exacerbating the relational problems is so right! Traditional psychiatrists are doomed to failure in their attempts to help psychotic people for many reasons, for example…

– Psychotic developmentally primitive people already have great difficult trusting, and are much more attuned to bad attitudes/relationships than good ones, as well as being somewhat unreceptive to good relationships at first. This combines terribly with the psychiatrist’s holier-than-thou role of telling the person they are fundamentally broken (brain disease) and directing them what to do in terms of taking neuroleptics and so-called symptom management. Today’s psychiatrists represent the apogee of what Harold Searles talked about when he discussed certain professionals looking down on their clients from a “cool, Olympian height.” Kernberg and Jeffrey Seinfeld wrote about how by controlling and directing the severely disturbed person’s actions, the psychiatrist could unwittingly strengthen the defense of all-bad splitting, i.e. causing the therapist to be viewed as more all-bad than he really is, while perpetuating the estrangement of the person’s vulnerable self from the needed internal holding/all-good object.

– Most psychiatrists simply lack the skill and training to effectively help psychotic people in a psychological or social way. They have not been given therapy training, and if they have; it is often simplistic DBT-type training focused on symptom management while harboring an underlying pessimistic attitude about real recovery. Donald Rinsley wrote about his work with hospitalized psychotic adolescents at the Menninger clinic in Kansas, and he lamented that he felt many of the most severely psychotic youngsters could not get well only because of a lack of well-trained therapists who understood how to be with them, contain their fears, and work painstakingly to build a trusting attachment. He wrote about the many mistakes such therapists make in terms of stepping into the role of the “bad object” (e.g. becoming the engulfing, controlling parental figure, or becoming the abandoning, rejecting figure) without even knowing it. This situation must be even worse today compared to the 1970s/80s when Rinsley was working.

– The use of neuroleptics unconsciously transmits the message to the young person that there is something wrong with them, they have an illness, etc. And it makes developing a real positive relationship and processing fear and rage impossible because the feelings are (temporarily) extinguished and the person’s cognitive capacity is diminished by the drugs.

I encourage you to write more about intensive individual psychotherapy as another treatment method with great potential to help – I know you already believe this, although I don’t think you’re such an experienced therapist yet.

Remember the metaanalysis I linked to before? Here it is again – showing how strongly psychotherapy often helps psychotic people if done long-term. People need to hear this message so much, that there is a treatment/approach that often works. Hope.

http://psychrights.org/Research/Digest/Effective/BGSchizophreniaMeta-Analysis.htm

Have you submitted this essay to any psychology journals? I recommend you to do so if you haven’t. Also consider other online outlets like Aeon.co . I would impressed if I saw you on Aeon. And what about NAMI and the APA? You know they would want to publish this! I would submit it to them if for no other reason than the entertainment value of seeing their (non) response.

Report comment

I would add that something of great interest to me in Hedge’s writing – that is also controversial – is his support for a limited degree of physical touching in psychotherapy, with prior consent between therapist and client of course. Psychotic people are often very estranged from their bodies in a variety of ways, for example, in not breathing deeply or fully due to the terror, in not being able to take joy in exercise, in not being able to hug and sit close to other people due to their fear of emotional closeness and their feeling that they are “bad”, in not being able to look others in the eye. So at an appropriate time physical touching in therapy – and in any friend or family relationship where one tries to help a very scared, enraged person – can be very helpful and calm a person down and let them know at a visceral level you are real, you are there.

The first body ego relates to the skin and touch… Rinsley wrote about how an absence of physical closeness in early childhood between mother/child tended to characterize the childhoods of the most severely psychotic youngsters that he worked with, those he called “presymbiotic schizophrenic”… those who would be considered to be in the autistic/out-of-contact phase according to Searles and in the earliest part of the stage 1 continuum according to Kernberg. The absence of physical contact and the primordial emotions of terror and aloneness that it generates are important in psychosis. Today’s therapists working with psychotic youth could learn much from Rinsley’s technical guidelines to approaching their families in his book, “Treatment of the Severely Disturbed Adolescent.”

http://www.amazon.com/Treatment-Severely-Disturbed-Adolescent-Rinsley/dp/1568212224/

Your reading list keeps growing Paris! But seriously I think you would be interested at how Rinsley tried to structure family approaches to psychotic youngsters and their families using many of the principles you are discussing. He developed intensive family and individual therapy programs for psychotic young people in American hospitals and communities in the 1960s and 1970s, before mass drugging and short-term treatment only took over. He had a lot of success and represents another diamond in the rough for you to look into.

Report comment

Hi BPDTransformation,

Thanks for sharing this wealth of knowledge(!) …and for some interesting reading material. I am familiar with a number of the people you mention, and look forward to perusing the works of the others.

To say a little more about my background (as it sounds like you may be interested in that), I have quite an eclectic background in my psychosocial training, particularly appreciating the core human dilemmas and existential and relational principles that I believe so many different approaches have pointed to, which is why I’ve been drawn to a number of different perspectives–particularly humanistic/existential, transpersonal, somatic, psychodynamic, and Buddhist/nondual. So I relate very much to most of the points you’re raising here.

I particularly appreciate the fact that mental health professionals are in the position to cause either great harm or great benefit to vulnerable people, though unfortunately, many don’t seem to really understand or appreciate their power in this regard. This is why my own personal code of ethics as a psychotherapist/psychologist consists of maintaining certain key ethical principles and continuously evaluating my own behaviour in the light of these, doing my best to empower the people I work with and to minimize the potential for any harm to them.

Although I incorporate a number of psychotherapeutic modalities, the basic foundation of my approach is Rogerian (empathy, genuineness, and unconditional positive regard), upon which I bring in various approaches that draw from attachment theory, psychodynamic relational, mindfulness, expressive arts, somatic psychology, Nonviolent Communication, etc. You can learn a bit more about my approach here, if interested: http://www.taurangapsychologist.co.nz/my-philosophy/4554777832

You mentioned intensive individual psychotherapy–I particularly enjoy Hakomi psychotherapy for intensive psychotherapy with individuals (and couples to some extent), as I believe it captures all of these principles and approaches in an elegant and powerful practical/experiential framework: http://hakomiinstitute.com/about/the-hakomi-method

…and I primarily use NVC (Nonviolent Communication) and EFT (Emotionally Focused Therapy–an attachment/systems approach) when working with couples and families, though also draw from other family/systems approaches.

Frieda Fromm-Reichmann said something to the effect that, “People in therapy are looking for an experience, not an explanation,” which I really resonate with. This is why I believe that an experiential approach (working directly with distressing experiences, distressing relational patterns, difficult beliefs, emotions, etc.) is generally more effective than simply offering explanations, trying to persuade people to think differently, etc., which is why I incorporate mindfulness, awareness of physical sensations, emotions, imagery, etc., in most of the work that I do (so I really resonate with your mentioning the importance of supporting people in working directly with their body/sensory experience, etc.)

Finally, I did consider trying to publish this on a more mainstream forum, but didn’t feel particularly hopeful of this being accepted in the forums that I feel are most in need to engage in this material (as you suggest, APA, NAMI, etc.) But I’m still considering my options in this regard.

Thanks again for your engagement with this material,

Paris Williams

Report comment

Paris,

Thank you for your response. I just now did read your Philosophy page and found it useful to understand where you come from. I like to read different approaches too, all of them except the brain disease approach 🙂

If it isn’t too time-consuming, I hope you will try to submit this and similar material to mainstream groups. Ask yourself what is the worst that can happen: it will get rejected, but at least the people (who I agree with you need to hear a broader variety of perspectives) who receive the messages will become aware that other viewpoints are out there, and may even be fascinated by what you have to say, even if they cannot admit to themselves or others yet that there is value in the viewpoint.

Report comment

Hi Paris,

I appreciate how clearly you explain how psychosis can develop in people as a result of deep intra-psychic conflicts between an urge to be safe and connected and a competing urge to be free and independent. You describe how this may arise when parents are unable to provide authoritative parenting which is warm and loving and also encourages autonomy and individuation in children. Ideally parents provide both solid roots and strong wings to their children.

I continue to wonder about other factors that may negatively impact families (parents and children) such as economic systems, (e.g. unregulated capitalism that puts profits before people), war, technology that is changing our connections to others in unforeseen ways, government spying and war which makes a certain amount of ‘paranoia’ almost expected, environmental collapse, unhealthy food, too many prescribed drugs, (especially when given to pregnant women or developing children) and religious or political fascism. While I highly respect and agree with your perspective, I have come to humbly appreciate the many complex forces that impact all of us as human beings. Existential stress is pervasive and can also contribute to psychotic crises for deeply feeling people. My hope is that we wonder together, create non-judgmental dialogue, tolerate uncertainty and give people experiencing psychoses and their families support and safe spaces to come through these challenging experiences. I think we, as professionals should hold our theories lightly and realize that there is great mystery in the human condition.

That said, your theoretical perspective is such a rich, humane alternative to the disease model which reduces human pain, especially psychosis to a biological illness. Thank you for all of your time, sharing and research.

Report comment

Truth in Psychiatry this is beautifully said.

Thank you Paris for your open and heartfelt responses to people’s comments about your writings. You seem to be all about creating open supportive dialogue.

Report comment

Thank you for your kind words.

Report comment

Hi Sa,

I appreciate your kind words, and for your seeing my intention to create open dialogue around these sensitive topics.

Best regards,

Paris Williams

Report comment

Hi Truth In Psychiatry,

I really like this quote: “Ideally parents provide both solid roots and strong wings to their children.” Well said.

I strongly agree with the points you make here about the need to acknowledge factors outside the nuclear family system that may lead to overwhelming and extreme states of mind. You may have seen that I tried to capture that with the following paragraph:

“Another point that needs to be stated here is that, as discussed above, the research is quite clear that many different factors may contribute to a person developing psychosis. Yes, relational factors, and especially childhood relational factors, do seem to be at play in probably the majority of cases of psychosis, at least those that have been thoroughly explored; but we are complex organisms, whose wellbeing is based on a multiplicity of factors occurring within multiple domains—physiological, psychological, social, environmental, spiritual, existential, etc.—and if we consider that psychosis is often a desperate strategy to cope with otherwise overwhelming experience, it becomes clear that multiple factors and experiential domains often converge to create such overwhelming conditions. So, in many cases, pointing towards any one single factor as the cause of a person’s psychosis is far too simplistic.”

I realize that I’m only lightly touching on this very important theme–that of the importance of these broader factors–as this particular article is focusing on the nuclear family. However, if you’re interested in reading more about my thoughts on some of these broader social factors, you may enjoy the following article:

https://www.madinamerica.com/2015/06/can-madness-save-the-world/

Best wishes,

Paris Williams

Report comment

Paris, I agree with most other commenters above, that your insights into the relationship between “psychosis” and familial and / or societal relationships are a much more valid and hopeful approach, than are today’s biological psychiatry’s reductionist “life long, incurable, genetic” “brain disease” theories.

And the mere existance of these DSM theories do result in egregious abuses by psychiatric practitioners with “power over” desires. Especially, as in my family’s case, and I understand likely in 2/3’s of all “schizophrenia” cases today, when the MO of the psychiatric practitioner is to deny child abuse, in order to profit off of covering it up.

And I do agree with your theory that the person stigmatized as “psychotic” is often just a person who is more sensitive, or one might even say more insightful, in regards to larger problems within the familial structure. In my family’s case, we had no problems within our small family (prior to psychiatric misdiagnosis, psychiatric stonewalling, psychiatric scape goating, psychiatric brain washing, and lots of different psychiatric anticholinergic toxidrome poisonings – a psychiatric drug induced toxidrome known to cause “psychosis”). But we ran into an entire religious “familial” child abuse cover up problem. Thankfully, others who’ve also now left the ELCA religion, out of disgust, are also pointing out the impropriety of religions functioning as child abuse covering up corporations.

https://books.google.com/books/about/Jesus_and_the_Culture_Wars.html?id=xI01AlxH1uAC

And thankfully, I was able to leave that child molestation covering up religious “family,” and did find another religious “family.” Including a kind pastor who was honest enough to confess that psychiatrists covering up child abuse for the paternalistic religions is “the dirty little secret of the two original educated professions.” Although, I do find it sad that none of the ELCA bishops or pastors I’ve spoken to yet are honest or ethical enough to work towards “personal accountability or shared responsibility.” I do have ‘tears in my heart’ for all those unrepentant religious and medical hypocrites, since I am of the belief I wouldn’t know about such crimes, if God didn’t. And I believe in the Old Testament, as well as, New Testament God, which means He does have a vindictive streak.

I do so hope we may some day elevate our society to one where all within understand all people (even those working for corporations and the “professionals”) need to abide by the laws of our country. And, since it does appear, according to the medical evidence, that the number one actual function of today’s psychiatric industry may in fact be covering up child abuse, by way of turning child abuse victims into “psychotics,” with the neuroleptic and other psychiatric drugs. Perhaps it would be wise to openly discuss whether maintaining such an industry actually benefits, more than harms, our society as a whole.

Report comment

Hi Someone Else,

Thanks for sharing some of your story with us. You point to a very powerful and toxic shadow element within I suspect most contemporary societies–childhood sexual abuse (and other kinds of child abuse)–and one that I personally work with quite a bit (a number of my clients are survivors of childhood sexual abuse and other kinds of child abuse, and have struggled with significant ongoing distress as a result of this), and I can really appreciate just how harmful this situation is.

You said, “And, since it does appear, according to the medical evidence, that the number one actual function of today’s psychiatric industry may in fact be covering up child abuse, by way of turning child abuse victims into “psychotics,” with the neuroleptic and other psychiatric drugs.”

I think you have a point here, though I suspect it’s probably a bit more complicated than what’s implied by this sentence. As you suggest, the evidence is clear that child abuse is very highly correlated with the later onset of extreme states of mind (i.e., “Psychosis”) and other distressing relational and emotional distress; and it’s also quite clear that this correlation is generally denied in mainstream psychiatric practice. Therefore, I think you’re right on that many people who have such experiences (childhood abuse) and subsequent distressing conditions do, as you say, very often get a DSM label and placed on psychiatric drugs, which then likely only exacerbates the situation.

However, my own sense after working within the field (generally skirting the edges of it, as I can’t tolerate working directly within it), is that many MH professionals (esp. psychiatrists) genuinely buy into their own “medical model” paradigm, and believe that such people really do simply have various biologically-based brain diseases and must be “medicated” for their own good. And for many of these professionals, I believe that the cognitive dissonance is simply too high to allow themselves to really take in the mounting evidence of the links between childhood abuse and psychotic conditions. Furthermore, these professionals typically have high paying jobs and are personally and professionally committed to maintaining the status quo to ensure maximal ease for their own existence–another factor I believe exacerbates cognitive dissonance when/if coming across the research suggesting the harm of the practice of “drugs and more drugs…” and the invalidity of their theoretical orientation.

So I have come to agree with you that psychiatry has generally come to function in covering up many shadow elements of our society (including childhood abuse), though I think that (a) many MH professionals are themselves oblivious/in denial that they are in fact contributing to this, and so are not necessarily acting in a way that is overtly malevolent (and may even be genuinely well intended), and (b) that what is ultimately being upheld by this industry is not merely the undercurrents of child abuse but, more broadly, the maintenance of a particular status quo in society that offers them a particularly high degree of power, prestige and wealth to such professionals. [This is why I like the term “social control agents” for those professionals who fully contribute to the mainstream “medical model” system, as I think that this generally has become more accurate than the term “mental health professional”].

You may enjoy this article, in which I explore some of these ideas a bit further:

https://www.madinamerica.com/2013/05/the-mental-illness-paradigm-itself-an-illness-that-is-out-of-control/

Best regards,

Paris Williams

Report comment

Thanks for the thoughtful reply, Paris. And in as much as I largely agree with your belief “many MH professionals are themselves oblivious/in denial that they are in fact contributing to [child abuse cover ups], and so are not necessarily acting in a way that is overtly malevolent.” (Although, I’ll point out that this does qualify these MH “professionals” as, at a minimum, at least a bit “delusional.”)

I will say I’ve read all my family’s medical records, which gives one insight into others’ viewpoints and motives. And I know the psychologist who initially misdiagnosed me, did so based upon lies and gossip, written right into her medical records, from her pastor and his best friends, at whose home the child abuse occurred. So this therapist was actually “overtly malevolent” from day one. But the psychiatrists I dealt with were seemingly completely deluded by the psychologist’s (and likely my paranoid of a non-existent malpractice suit PCP’s) lies for a long time. Thus the psychiatrist I primarily saw, was not seemingly initially “overtly malevolent,” just completely delusional.

And once my family’s medical records were finally handed over by some decent, and disgusted, nurses in my former PCP’s office. And I confronted my psychiatrist with the fact I’d been handed over the medical evidence of the abuse of my child, and the medical evidence of the psychiatrist’s incorrect, and extremely delusional, opinions about who I am and about my background. That psychiatrist literally declared, in his medical records, that my life was a “credible fictional story,” no doubt out of extreme embarrassment at his completely delusional belief system.

And then kicked in my psychiatrists’ abuse of power towards the “maintenance of a particular status quo in society that offers [professionals] a particularly high degree of power, prestige and wealth….” Despite the fact my psychiatrists had malpractice insurance to make proper amends for what they did wrong, and the reality that one of my psychiatrists even mentioned in his medical records that legally he needed to contact DCFS, if I did not agree to send my, then largely recovered child, to his child psychiatrist friend to be drugged, which I did not agree to do.

The subsequent cover ups included my former psychiatrists eventually misinforming subsequent doctors, resulting in my being medically unnecessarily shipped to a doctor whose now been arrested by the FBI, for having lots and lots of patients medically unnecessarily shipped long distances to himself, “snowing” patients, and performing unneeded tracheotomies for profit. Here’s that doctor, V R Kuchipudi’s, eventual FBI arrest warrant.

http://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/usao-ndil/legacy/2015/06/11/pr0416_01a.pdf