A recent study, led by the researcher, Dr. Anne Cooke and her team in the UK, investigated the experiences of psychosocially oriented practitioners who work within systems dominated by the medical model of mental distress. The researchers qualitatively analyzed interviews conducted with psychologists that were designed to understand their first-person accounts better navigating the dilemmas that arise a result of the tension between these two models. Their findings were published in the journal Psychosis. Overall, Cooke found that psychologists face difficulties when attempting to challenge the medical model, even when they identify that as a crucial responsibility:

“The current study has illustrated how in a medicalized system, offering an alternative perspective can be difficult, despite many psychologists seeing this as one of their key roles,” they write. “It has implications not only for clinical psychologists but also for other psychosocially oriented workers.”

Cooke and colleagues summarize the medical model as the view that mental health problems are “illnesses like any other.” Such problems, therefore, are understood as arising out of pathologies in the brain or as genetic abnormalities. In alignment with this view, the medical model approaches center around diagnosing individuals’ behavior/presentation, the reduction of pathological “symptoms,” and medical intervention.

Critics of the medical model have outlined essential critiques of the theory. These include the lack of evidence for biological causation, the problems posed by a structure in which a panel votes into existence diagnostic categories, and numerous other scientific, ethical, and practical issues. The importance of integrating alternative frameworks has been one response to these critiques. However, Cooke and colleagues point out that the medical model remains dominant.

“Despite the attempts at integration,” they write, “the medical model arguably remains dominant within most Western mental health systems and is reflected in both their structure – with services delivered from hospitals and clinics – and their legislative base.”

The psychosocial model has been put forth as an alternative theory and approach. Rather than centering around biology, the psychosocial model prioritizes the role of relational, interpersonal, and social factors that shape individual wellbeing. Cooke and team argue that this not only counters a medical model but represents a counter-cultural approach that challenges the status quo. Essentially, the psychosocial model contends that all behaviors and experiences are understandable and meaningful within context, even if the behaviors themselves are problematic.

These differing viewpoints can create tensions and obstacles for professionals. Not all professionals believe that conflict exists between psychosocial and medical approaches; however, some senior psychologists “have urged their colleagues not to ‘jump ship’ from psychological to medical explanations and to resist the pressure to adopt medical discourse and practices.”

Although there is little information on the experiences of clinical psychologists or other practitioners who work in medical model dominated systems, they are nevertheless encouraged “to engage in ‘constructive conflict’ with colleagues in order to acknowledge and address theoretical differences and to offer an authoritative and constructive counter-balance to the medical model.”

To address the gap that exists between this recommendation and the information known about practitioners’ real-world experiences, Cooke and colleagues sought to investigate the latter in this study. They aimed to systematically explore the experiences of psychosocially oriented practitioners who worked in these systems and questioned: “what the implications of engaging in ‘constructive conflict’ could be.”

They asked the following overarching research questions:

- How do clinical psychologists who are critical of the medical model experience working in teams where it is dominant?

- How do they experience challenging it in their teams?

- What are the associated personal and professional challenges?

- How do they respond to these challenges and what enables them to remain committed to working in the mental health system?

Cooke and team utilized a grounded theory analysis to develop a theory that is systematically derived from the lived experiences of the interviewees. They conducted this analysis through the lens of a critical realist epistemology which recognizes that although perspectives represent a particular lens of viewing the world, they contain valuable data about participants’ real world “experiences, views, feelings, and actions.”

Psychologists shared that they felt a general discomfort with the hegemonic embeddedness of the medical model within their place of work. They noted that this dominant perspective trickled into clinical team assumptions and meeting discourses. The researchers describe this discomfort:

Psychologists shared that they felt a general discomfort with the hegemonic embeddedness of the medical model within their place of work. They noted that this dominant perspective trickled into clinical team assumptions and meeting discourses. The researchers describe this discomfort:

“They felt the focus was predominantly on individual deficits rather than on people’s context and circumstances, and that diagnoses obscured the impact of life events. They worried that many practices replicate wider power imbalances and earlier traumas and abuses that people have suffered. They felt that teams are often blind to the shortcomings of treatments.”

Upon experiencing this discomfort, the psychologists were left to engage in an experience of “making sense” of these practices. This involved reflecting on the difficulty involved in changing systems and the language barrier that poses additional complications in the endeavor to subvert a dominant discourse.

In addition, the psychologists’ discussed that the “stuckness” of systems in a medical framework can also be attributed to psychiatrists’ fear of losing power and influence as well as the overall tendency of practitioners to want to fall back on a purportedly “safe” and “certain” option, even if false, in the face of “complexity and extreme distress.”

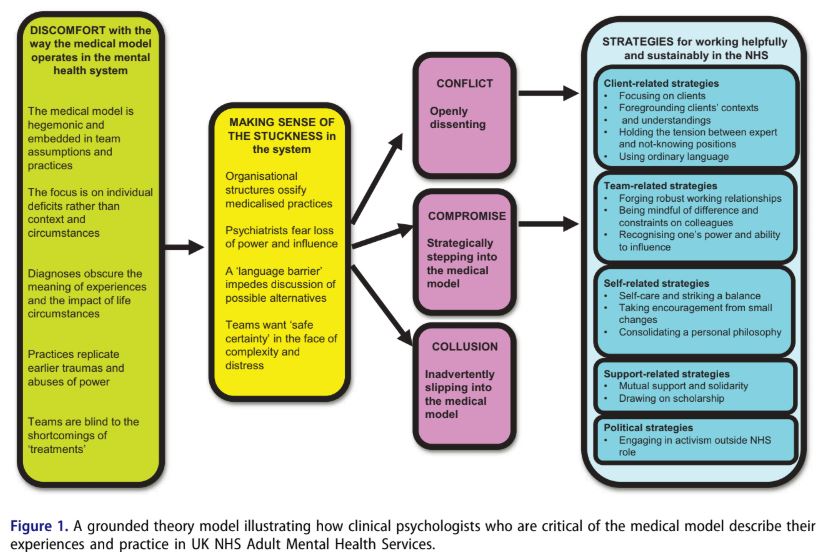

Finally, the interviews demonstrated that there were three ways that psychologists tended to respond to the hegemony of the medical model:

“The first was open dissent (‘conflict’). The second was strategically ‘stepping in’ to the model (‘compromise’). Thirdly, some participants described at times inadvertently slipping into ‘colluding’ with the medical model.”

These three responses were discussed further by the researchers alongside the strategies that practitioners disclosed enabled them to continue their work in ways that they hoped were constructive.

Cooke and team point out that these findings provide evidence that practitioners are finding ways to survive and help despite the hegemony of the medical model:

“It is nevertheless clear that it is at least possible for practitioners critical of the medical model to find ways of surviving and making a difference within our current, medically dominated mental health system.”

They conclude:

“We hope that not only psychologists but other workers will find it useful when grappling with their own dilemmas.”

****

Cooke, A., Smythe, W., & Anscombe, P. (2019). Conflict, compromise, and collusion: dilemmas for psychosocially-oriented practitioners in the mental health system. Psychosis, 1-13. DOI: 10.1080/17522439.2019.1582687 (Link)

Very little about any “help” I have encountered with the medical model has focused on a good external support network. There have been times in my life where the only time I had anyone to talk to was a paid therapist, and even those therapists focused on the things that haven’t been shown to improve well being. It was about making sure I kept my job and health insurance so I could keep being treated. It wasn’t about finding community and meaningful work. Everyone was dispensing things at me, meds or a timed fifty minute block of assistance, but I was still alone almost all the time. My last therapist was the most depressing of all of them, she was on eight different medications before “they worked” for her. She was clearly gaining weight and then stopped working suddenly. I needed a better world to live in. I’ve got a better network now, but I’ve gotten used to be isolated and it’s hard to interact with it.

Report comment

I found in the US that the psychologists, social workers, school social workers, and even the so called pastoral counselors all fall in the “compromised” and “colluding” with the medical model catagory.

And they all seemed to have as a goal, according to their medical records, destroying “good external support networks.” One of my psychologist’s first statements, in her medical records, was something to the effect of “what to do w/ 4 yr old girl,” implying she was hoping to steal my daughter from me?

One of her last comments, when she had to stop seeing me, since she was incabable of discussing the etiology of my psychiatric drug induced illness, was something related to the fact that at least she destroyed my marriage. But all her medical records do indicate she had “conspired” with a pastor and some child molesters to cover up the abuse of my other child.

I found the schools to be not remotely concerned that a child went from a “school for gifted children,” into remedial reading in first grade, after the child abuse. However, once my child had largely healed from the abuse, and got 100% on his state standardized tests in 7th grade, by 8th grade the school social workers wanted to get their hands on my child.

I found the social workers to be the criminals, left to cover up prior malpractice for doctors, by medically unnecessarily shipping patients to now FBI convicted doctors. Whose MO is having lots and lots of patients medically unnecessarily shipped to them, “snowing” them until they couldn’t breathe, so those doctors could perform unneeded tracheotomies on people for profit.

And I found that the pastoral counselors in the hospitals do not believe in God, or the concept of “treating others in a manner that you’d like to be treated,” which is a main tenant of Jesus’ theology.

So I’d definitely say in the US, most the counselors are in the “compromised” and “colluding” with the medical model mode. To the extent I’m not certain that it is possible “for practitioners critical of the medical model to find ways of surviving and making a difference within our current, medically dominated mental health system.”

I know some MiA commentators are former practitioners who didn’t want to continue working within the US mental health system, constantly having to battle that corrupt, “invalid,” and “unreliable,” system.

Report comment

The bio medical model “helps” by cutting you off from friends, family, and mainstream society as a whole. Like a cult.

This helps explain the animosity between Psychiatry and Scientology. 😀

Report comment

Being a psychosocial oriented mental health practitioner working in an organization that purports the biomedical model, this is so validating to read. I am relieved to know studies are being done on this and that I am not alone in feeling conflict with the biomedical model. It can be so disheartening and frustrating when everyone around you feeds off the biomedical model as if it is the irrefutable truth that practitioners must hound into their clients. Seeing clients feed into it, and it harm them more than help, leads me to feel the biomedical model of oppression will continue.

Report comment

I’m glad you mentioned oppression. The big shortcoming of this article is that it makes it seem like there are two equal ideas competing to see which one comes out on top. This is not what is going on. One idea is being FORCED on people, both practitioners AND clients within the system, and the other is being actively suppressed, not because the dominant one is “better,” but because it is more financially rewarding for certain people and because it helps those in power relieve themselves from any responsibility for the damage they cause. I eventually concluded that I had to get out of the profession completely, because change from within seemed impossible and because I felt I was colluding just by participating in such an oppressive system, even if I could help a small number of people along the way to escape or minimize their experience of oppression within the system.

Report comment

I would say the medical approach, e.g. antidepressants, require less human resources. A cost-reduction approach would be, in a socialized medical system, that the first course of action be a pill, if it doesn’t work after say 6 months, augment with psychotherapy (costs more). If that doesn’t work, ECT (an atomic bomb), or if your against it, something like rTMS. The force you mention, is just what your insurance is prepared to pay. Psychotherapy, in a society with relatively high incomes, costs more than a pill. They want you to become productive again and minimize costs in the process. They are all mostly bogus treatments.

Report comment

They may cost less in the short run, but a lot more in the long run.

Report comment

That’s true Steve, but sometimes a non drug (dependent) approach can cost less in the short run and in the long run.

I believe that it’s possible to get the help thats needed in the community. If you look at people that Recover this is often the path they take.

Report comment

They’re not smart enough to be Psychologists if they don’t know that the solutions can be found in “Psychology”. Nobody has ever recovered through the Medical Model.

Report comment

Psychiatrists that are afraid of losing power to psychology, and psychologists with the same fear. Compromise. Share the wealth. Psychotherapy and drugs.

Report comment

Who’s paying for all of this: A “Schizophrenic” in the community costs about the same as a Medical Doctor; a Recovered Person in the community costs nothing.

Report comment

To all you Trekkies:

“Darn it Jim! I’m a doctor. Not an economist.”

Report comment

My favorite was, “Damn it, Jim! I’m a doctor, not a tree surgeon!”

Report comment

Maybe people at large should take on the mental health care provider role. We’re human, so we know how we feel, and what makes us feel better or worse. Then we ask those in distress all about how they feel, we listen carefully, we get more kind than we have ever been before, and who knows, it might even work.

Report comment

..As far as I know the Danger Aspect of “Schizophrenia” is in the taking of “Medication” – not the other way around.

Report comment

i think psychosocial solutions have more probability of lasting success in places -other than- the US. I see this research came out of the UK. I’ve noticed that a lot of “critical psychiatry,” psychosocial research, etc. come out of the UK. In the US…

obviously, psychiatry and psychology reflect the society (as a whole) and also the community. God help you if you’re in a ‘red state’ seeking a real solution; no ‘professional’ will, in all likelihood. Not that the ‘blue states’ are always all that ‘progressive…’

some of them seem to simply use the state hospital system more frequently, since that is “treatment,” not “punishment,” etc.

anyway…thanks for the summary of the new research. While I’ve long feared that because of ‘austerity measures,’ the UK might end up like the US…it appears there’s hope “over there,” yet. In the US…

we have TV ads for Rexulti, usually right before adverstisements for disability lawyers (where I live). Trump is not only still in office, he’s planning a 2020 run. And while the psychosocial treatments are all about talking and communicating and reflecting…

most ‘treatment’ available for ‘severe mental illness’ in the US is really about shutting people/”patients” up, one way or another. 🙁

Report comment

I prefer living in a Red State BECAUSE of the lack of “help.”

“If I knew for a certainty that a man was coming to my house with the conscious design of doing me good, I should run for my life.” Henry David Thoreau.

Report comment

Yes, excellent point. When Obamacare came out a lot of natural healers predicted an uptick in iatrogenic disease due to more people being exposed to the medical system.

Report comment

All psychiatric “research” is bogus by definition. People need to start getting this.

Report comment

Yeah I survived — in what way has anything changed here due to Trump? Nothing I can see. Psychiatry is embraced by both factions of the U.S. dictatorship, even more so by “liberals.” Heads I win, tails you lose.

Report comment

Mental Health, Inc. takes on a higher level of authoritarianism and punishment in many red states. -some- red states are still gung ho about the state hospitals, for instance. southern culture+Trump culture+psychiatry=Hell on earth.

to be fair, not all red states are the same, even in the Trump era. Some are shredding the state hospital system down to the bare minimum…that way, rich people in their states don’t have to pay as much $$$ to confine poor people. Prisons do it for far less, anwyay.

Report comment

Good article, because it gives psychologists ways to manage within a system and deal with colleagues that suffer from context blindness. The “ordinary language” strategy should be used with colleagues too and they should be reminded that labels provide no explanation, cannot inform any “intervention/treatment” and are a lazy and simplistic way to refer to people and what they are going through

Report comment

Black and white thinking is undesirable to me so I was surprised by comments criticizing a compromise with the medical model. As a therapist I prefer using all the tools and perspectives available. I was impressed with Peter Kramer’s idea that certain events can affect the hardwiring of the brain. I work on resolving psychosocial issues while being open to the benefits of some medications. I have never felt that the medical model denies the need for psychosocial supports and therapeutic models. Remaining behind one fence or another is not helpful to clients.

Report comment

It would be interesting to hear what this compromise would look like. Is it where you tell clients that anti-depressants are not actual medication as there is no chemical imbalance to be corrected but to use it anyway as it will “take the edge off” so that they can be “stabilised” enough in order for them to be receptive to your magical techniques that can rewire their broken brains?

Report comment

Good point Gerard!

Assuming there was something wrong with someone’s brain–since they have no idea what the problem is–all bio psychiatry consists of is lots of mind altering drugs and other forms of random brain damage. It’s not “like insulin for diabetes.” They have no idea how they’re screwing with the human neuro chemistry. It’s not like removing cancer from the brain the way a neuro surgeon would.

Know why I’m radical? I’m very angry at being lied to. By NAMI, the psychiatrists, everyone in the Mental Illness System. They also lie about us, and slander the character of their patients. No other medical specialty does that. 🙁

I read that article by Doc Pies in the APA Journal. The cold-blooded fraud and his fellow cons seem to be laughing up their sleeves at the “uninformed” public they pulled one over on. Disgusting!

Escaped this grotesque hoax after 25 years. Living in poverty, crippled from the fake “medicines.” I feel like one of Dr. Farid Fata’s victims. But no one will listen to people like us. So the inhumane barbarism continues!

It’s just destroying normal brain functions. They could achieve similar benefits with baseball bats, icepicks, and street drugs like heroin and meth. Only that would not LOOK like real medicine. It wouldn’t LOOK scientific. PR is all that counts after all. 😛

Report comment

I was very surprised in 1983 when a Psychologist in Galway Psychiatric Unit (Ireland) assured me that everyone in the Psychiatric Unit could fully recover without medication. He also told me that he wasn’t anti medication at all, if it helped.

I didn’t believe him at the time because I was fully convinced that I couldn’t recover myself. I had tried to stop taking “my medication” and had ended up in a state, and back in Hospital.

Report comment

What really gets my attention is when a physician puts a child (or anyone for that matter) on an antidepressant and fails to make a referral for psychotherapy. This is a terrible standard of care still widely practiced. If a child is that depressed…I want to know why. What should be obvious to primary care physicians; the diagnosis and treatment of a child is most certainly going to require a thorough evaluation of the parental coalition. Most behavioral problems in a child involve the parents…who are (almost always) open to the role they may be unintentionally playing. To see the etiology resting solely within the child’s biochemistry reveals the limitations of “the medical model”, displays marketing goals that perpetuate pharmaceutical misinformation, reflects insurance companies distortions, and finally is often unchallenged by psychiatry that went full in on the medical model with the advent of managed care. The biopsychosocial model is indeed more comprehensive diagnostically AND to the treatment strategies that open up with this wide field view. No one is arguing that the research and diagnostic considerations into neurochemistry should cease to exist. This is not either/or decision making however, the distortion toward organic factors is real. Finally…there is even a more comprehensive view that includes the biopsychosocial model called Integral Theory for the interested theoretician…but this is another discussion. This article was very important for the public to learn Zenobia.

Report comment

There is actually no reason EVER to give “antidepressants” to a child, as there is no evidence that they “work” even in the short term. Of course, they don’t really “work” for anyone in the long run, but apparently the placebo effect is stronger in adults, I guess. Even psychiatry’s own researchers admit that kids don’t benefit from “antidepressants.”

Report comment

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FscIgtDJFXg

I share with you a very nice melody that popped up in my mind as I was reading this article. “I can see clearly now, the rains is gone” …

That’s how I feel now that I’m out of the medically oriented battlefield. The line is thin between compromise and collude. Many times I felt I was slipping in, the worst being afterwards. It is very disturbing to come to realize that You out aside your convictions and beliefs for fear of retaliation, by lack of certainty or by having sied with the good doctor or in order to please or relieve those who where disturbed by the “mentally disturbed”.

After 35 years working as a psychologist in the public sector, initially in the addiction field where there was hardly noninterference by the medical actors, we got gradually invaded over the last 10-15 years of my career. I was eventually “rented out” to the mental health facilities -because they where totally “screwed” with all the comorbidity issues and lastly jumped in, full time in a psychiatry department. That last stop ended after a short 3 months trial and I was kicked out, most probably because I was more on the conflict side of the equation than the other way around. They couldn’t fire me for lack of qualifications but, part of the reason given to me was an apparent difficulty working with the team of psychiatrists. So, I’m now out of the rain and can see quite clearly. I really tried hard to compromise but it was a lost battle from the beginning. And one thing I can say for sure is that psychologists cannot have honest, straightforward discussions with all of their psychiatrist colleagues. Many, not all, but a sizable number are unwilling to listen, to hear and to give psychologists any credibility. And guess who usually wins when a power struggle appears ? I’ll let you fill in the answer. But a hint : I am now working for a private EAP, and relieved. Or re-living …

Report comment

Love the chart in the middle, but it’s a gross overgeneralization that providers don’t want to give up their power. There are a great number of providers beginning to shift from collusion to conflict as needed to advocate for change in a high pressure managed care environment they are attempting to push against. Certainly there is a bell curve with this as with anything, but I’ve seen at least some effort to level the hierarchy with the increase in education about trauma informed care. Thanks for writing this! A lovely read!

Report comment

Making gross generalizations about therapists leads to errors in judgment. There is a huge range of therapists/counselors out there with different orientations and priorities. I was fortunate to have one who was very empowering and focused on me getting better at accomplishing my own goals. She was very much “trauma informed” and the results were quite significant for me. Of course, this was back in 1981 before the DSM III and the ‘chemical imbalance’ model had totally taken over, but there are still folks out there doing good work, though I most definitely consider them to be very much in the minority these days. I’ve certainly spoken to folks who became more radicalized through therapy, not because the therapist wanted to “radicalize” them, but because as they woke up to what led to their so-called “mental illness,” they realized that radicalization was the path they needed to take. I’m one such.

In fairness, I know a lot more stories about therapists who were either ineffective or were invalidative and destructive, and more and more these days believe wholeheartedly in the DSM and in drugs for “mental illnesses.” So I’d be super careful looking for a therapist, actually, I probably would not consider it for myself these days because I know more than most of them. But there are still some competent people out there.

Report comment