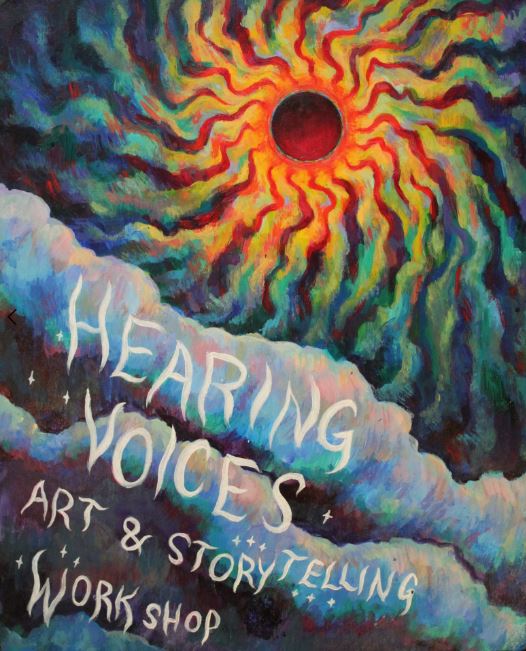

A new article published in Health and Human Rights Journal draws on the principles of the Hearing Voices Movement (HVM) to call for a rights-based, trauma-informed, and socially grounded approach to psychosis. The author, Rory Neirin Higgs, is a non-binary artist, writer, and disability activist living and working in Vancouver, where they serve as a facilitator for the BC Hearing Voices Network.

Higgs provides an overview of the HVM, outlines an approach to understanding the social origins of psychosis, and argues for an approach to mental health that counters the medicalization of social realities many individuals who have experienced ‘psychosis’ endure.

“The role of power and disempowerment in the lives of those diagnosed with a psychotic disorder, I will argue, must remain a focus in building on the work of the HVM. Policies and therapies that fail to address ongoing structural and economic violence will inevitably replicate the same harmful logic: that mental distress is a matter of individual dysfunction, that be dealt with through (sometimes unwanted) individual-level interventions, rather than an understandable reaction to frightening, oppressive, and demoralizing circumstances. A non-pathologizing approach that remains attentive to large issues of injustice is called for,” Higgs writes.

The Hearing Voices Movement (HVM) is an international grassroots movement that promotes alternative ways of understanding the experience of those who hear voices (auditory verbal hallucinations), which is generally associated with “psychosis.” For decades now, the biological approach to understanding psychosis has been the dominant viewpoint among professionals and the public, despite substantial evidence linking psychosis to traumatic experiences and social deprivation.

The origins of HVM are attributed to conversations between Dutch voice hearer Patsy Hague and her psychiatrist, Marius Romme, in which they met her voices with curiosity and investigated the meaning of the voices. Through their work together, they brought together people who experienced hearing voices, and Romme and his partner Sandra Escher went on to spearhead further research gathering voice hearers. Their work made it apparent that many people who heard voices never had contact with psychiatric services or felt the need to seek treatment. Additionally, many voice hearers were able to link their experiences to a broader social or traumatic context.

The HVM challenges the viewpoint that experiences of psychosis are best treated as biogenetic diseases, and invokes an ecological framework that centers the knowledge of those with lived experiences of hearing voices in the context of their culture, life history, relationships, and socioeconomic status.

Support for a social etiology of psychosis builds on evidence linking adversity and psychosis. A myriad of social stressors such as poverty, isolation, racial discrimination, migrant status, and childhood trauma have been associated with future ‘psychotic symptoms.’ With the knowledge that symptoms of ‘psychosis’ are shaped by and responsive to social factors, participants in hearing voices groups are often encouraged to “engage their voices as disowned parts of the self that contain difficult emotions, embody core beliefs about the self and the world, or represent the phantoms of past survival strategies.”

However, the link between adversity and psychosis has complicated the medical model, making it difficult to differentiate between ‘psychotic ‘and post-traumatic or dissociative diagnosis. This has led to a variety of new diagnostic models, such as a call for the “trauma-genic neurodevelopmental model” of schizophrenia, while others advocate for a “unified theory of childhood trauma and psychosis,” as well as a “psychosis continuum.” However, the HVM takes a depathologizing approach to the experiences gathered under the term ‘psychosis.’ Those within the HVM argue:

“Phenomena such as voices and visions fall on the spectrum of human diversity and need not be understood through a disease lens. To many of the movement’s proponents, applying the label of psychiatric disorder is seen as disempowering and instilling a sense of fear and hopelessness.”

The lens of cultural psychiatry points to the complexity that psychiatric diagnoses are culturally bound and based on socially constructed ideas of what is pathological or aberrant. Further, cultural neuroscience holds that culture is embedded in and enacted by our cognitive processes, and therefore how we conceive of distress is shaped by cultural metaphors and idioms. The dominant cultural vocabulary for distress relies heavily on the neurological disease-based structure and is hardly the only cultural vocabulary that exists to convey distress, albeit the dominant one in the West.

The author goes on to discuss how medical professions have a long history of “biologizing social facts” for systems of oppression to maintain themselves. Drapetomania, or the pathologizing of enslaved Africans fleeing captivity, is a quintessential example. Such concepts have justified racist and eugenicists political projects throughout history. The further pathologization of responses of Black Americans to oppression in the civil rights era has been said to have shaped the modern diagnosis of schizophrenia as a predominately Black disease.

Higgs argues that a trauma-informed approach to mental health must ultimately be a political approach that concerns itself with changing the present social conditions in addition to charting the past. Avoiding the discussion of social problems in the conception and treatment of psychosis maintains current systems of oppression and shifts the focus to an individual’s internal ability to cope.

Medicalizing social problems eclipses structural inequality and violence by focusing on how symptoms manifest at the individual level. The survivor-led activist collective Recovery in the Bin cautions that “as long as the onus lies on the individual to ‘recover’ from the harm inflicted by systems of power far beyond their control, the workings of the latter remain obscured, and the material needs of the former go unaddressed.”

Ultimately, insights from an interdisciplinary approach coalesce with the HVM’s urge for a social approach to mental health and a novel paradigm for understanding voice-hearing. For this to happen, it must be recognized that the right to health is not limited to clinical settings but extends to the social determinants of health. Higgs writes:

“Asking that disenfranchised people and communities interpret their distress as the fallout of traumatic events is insufficient when the traumatic conditions are ongoing. Additionally, it is important to consider the appropriateness of medical approaches to a problem that relates not only to health but to human rights issues and abuses in a variety of domains.”

Efforts to integrate respect for individual meaning-making and self-directed treatment, such as the British Psychological Society’s Power Threat Meaning Framework, are a step forward. The Power Threat Meaning Framework calls for a socially informed, rights-based approach outlining not only the necessary changes for clinical practice but legislation and policy concerning economic, racial, and gender injustice.

Higgs calls for further collaboration between both experts by experience and educators to ensure that the insights emerging from the HVM continue to guide understandings of health.

****

Higgs, R.N. (2020). Reconceptualizing Psychosis: The hearing voices movement and social approaches to health. Health and Human Rights Journal, 21(2). (Link)

Thank You Madison Natarajan,

I appreciate your inverted comma treatment of ‘Psychosis’.

I noticed this on the MIND WEBSITE:-

https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/drugs-and-treatments/antipsychotics/alternatives-to-antipsychotics/

“..What if I don’t want to take medication?

Many psychiatrists believe that severe mental health problems like schizophrenia must be treated with medication, but if you don’t want to take antipsychotics, there are alternative treatments you can try.

You may find it’s possible to manage your symptoms, or to make a full recovery, without medication. This page covers:

Talking treatments

Arts therapies

Ecotherapy

Complementary and alternative therapies

Peer support groups

Healthy lifestyle changes…”

Report comment

A problem I can see with the “Hearing Voices Network” in London is that they only seem to have meetings “during normal working hours”, whereas most Peer Groups have meetings outside of normal working hours.

Most people are unlikely to be available between 9am and 6pm to attend a London HVN Meeting, so the potential for people to gain or to contribute is very limited.

Report comment

“For decades now, the biological approach to understanding psychosis has been the dominant viewpoint among professionals and the public, despite valid evidence.”

“understanding” has never been part of psychiatry. Psychiatry prefers to “get rid of”. Getting “rid of” and control, is not even close to “trying to understand” or being curious.

Honestly I think a LOT of psychiatrists are tired of the power. They see it’s not working nor is it anywhere close to resembling “health”, nor is any of it “treatments”. It is high time for those psychiatrists to stand up and be counted for being human and not robots of the APA.

They are all simply existing in jobs, not care. Most are simply repeating and regurgitating.

Common sense and “understanding” and their knowledge base/education would make them understand much better than the public, that the pathologizing is a farce and hoax.

Until psychiatry has the conversations that need to be had, they will fail and cause much more distress.

These conversation WILL NOT happen, unless in the secret spaces that a few psychiatrists can discuss their inner voices of reason, but it will never be heard by the public.

Report comment

I’m afraid that having an ‘urge for a social approach to mental health’ will lead to dead ends, at times, just like the biomedical approach has. When any of us force fit mental health/trauma into a preconceived paradigm to fit our proclivities, then it closes us to the things which don’t fit into that paradigm…and not all trauma is socially/culturally based by any means.

This approach by HVM is very concerning, even if it is a little better than the biomedical approach.

Sam

Report comment

“Support for a social etiology of psychosis builds on evidence linking adversity and psychosis.”

I do agree, social factors may likely result in “psychosis.” But this would NOT be proof of a “lifelong, incurable, genetic illness,” as has been fraudulently espoused by psychologists and psychiatrists for decades.

However, the “mental health profession” does need to confess to the iatrogenic etiology of “psychosis” as well. Given the reality that every doctor is taught in med school that both the antidepressants and the antipsychotics can create “psychosis,” via anticholinergic toxidrome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

Until the “mental health” workers confess to the medically known iatrogenic etiology of “psychosis,” all their claims that they care about “human rights issues and abuses” are just hypocrisy. Since it is the disingenuous segment of “mental health” workers, who have been, and still are, the systemic human rights abusers.

Report comment

interesting that every once in a while a shrink will get a “poster child” and “poster mom”. And interestingly all three of them write about a certain drug. And interestingly, it will be a new drug.

Report comment