It is uncomfortably difficult to look at Phoebe Sparrow Wagner’s art.1 That much is intentional—it is unlike so many soft and serene scenes dotting the history of art. Instead, the artist relies on the ability of the image to shake up the viewer’s sense of wellbeing and security. The reason: to allow the average individual to better identify with the plight of a mental patient.

Diagnosed as schizophrenic, Wagner has railed against psychiatric labeling, psychotropic drugs, and dubious methodologies used to “treat” mental illness. At one point, a hospital doctor tried to force a designation upon her, when she replied quite simply, “Look, I’m not schizophrenic and I don’t like medication. It makes me feel drugged.”2

However, she also learned the hard way that, in those environments, argumentation (and even mere questioning) might lead to an excuse to dole out still more mind-numbing drugs or impose heavy-handed monitoring, including seclusion and restraint. Indeed, for patients like herself, psychiatric “care” has often relied upon a dialectic of fear—the exact opposite of what is needed for those already traumatized by psychosis and problems in living.

Certain pictures rendered by this artist problematize that trope and simultaneously defy the viewer’s desire to peer deep into space. In works like Not Waving but Drowning, all the visual information is made parallel to the picture plane. It is littered with a robust feast of psychological iconography: an eye dominates the upper field, as bloodshot as it is “all-seeing” or “provident”—perhaps a side effect of so much drugging. A cross wrapped with barbed wire is inserted into a chemical beaker at the right-hand side, seemingly signifying an unholy experimentation. There is a human head in profile commanding the center of the work; and the titular drowning figure emerges from a brain/body of water inside it. (No one seems to be coming to her aid.)

The viewer may be struck by certain text wrapping: “leper,” for example, distinguishes a bell at the left—a biblical symbol of alienation. Meanwhile, a heightened feeling of both danger and ennui spreads like a disease, and any relief is quickly blocked out. Red liquids with black “bio-hazard” indicators repeat in the upper-left and lower-right corners, symbols that the sufferer may have “contaminated” the environment somehow.3 Through these collected clues, the artist lets us know we are in an entirely different societal domain, one where common goodwill toward the Other and basic human rights can quickly diminish altogether.

A further look at Wagner’s work will bear out Not Waving’s complex, planar design. In the drawing Everything You Touch You Destroy, we are given a glimpse into the horrors of psychosis and dysfunctional psychiatry, combined. The very title likely refers to the befouling “voices” that the artist has suffered.

In 1999, a psychotic episode involved the idea that the world was ending, that that was her fault, and that she “didn’t try hard enough to warn people” of the perils of the end.4 Guilt over sins not committed has plagued Wagner, sometimes manifested as voices. Here they appear as a narrative on a script that turns into a spiral, winding into a tortured figure’s ear. (She is gagged by an unseen authority and cannot speak to her plight.) The voices accuse, negate, and tell her to do strange things, like self-harm. They are not neutral or benign: “Will you kill you Pam Spiro, Spam pam pam, kill you will you…”5

The serpentine quality of the spiral is echoed by the blood-red, venomous snake at the right—iconographical symbol of evil and temptation, stemming from archetypal descriptions of the Garden of Eden. Snakes also appear on the Caduceus of Hermes, typically used as a symbol for medicine in the U.S.—a fact the artist has emphasized.6 The “leper” bell repeats here, as do the cross and eye motifs, the latter now with a tear. One is reminded of Wagner’s poem “Fusion,” which reads: “If I looked you in the eye I would die.”7 A “peace” symbol is barely visible in the far-left corner, but it is drowned out by the white noise of so many traumatic visuals.

Another body of images by Wagner highlight the crudity of forced psychiatric treatment. Optics of Involuntary Treatment: What They Don’t Want You to See… depicts the use of 4-point and 5-point restraints, among other abuses. Special glasses and lenses are used to “frame”—and thereby actually see—what is ordinarily not seen. One pair of glasses reveals an individual on a hospital bed with restraining belts around her feet, hands, and chest. Another vignette shows a police officer escorting a shackled figure. Elsewhere, five people pin down a naked individual in order to restrain her (and, presumably, forcibly medicate by injection).

Handcuff openings act as “windows” into worlds of seclusion. The U.S. flag appears above in reverse, as like a mockery of the civil liberties it is so often associated with (e.g., freedom or due process of law). It might also be an allusion to the artist Jasper Johns, who famously incorporated flags into his work. Alternatively, as part of her psychosis, Wagner once had to signal a patriotic salute to the flag, as spies were hunting her down for capture.8

Five “watchers” seem to preside over the scene—figures who were part of Wagner’s hallucinations, governing her actions on earth and appearing in her Watchers at the Tree of Creation. In the poem “Paranoia,” she wrote: “Someone is always watching you, watching / and waiting for whatever is going / to happen to happen.”9 A snake-like figure makes another appearance, this time with a human head and rattle. As “optics,” these do not bode well.

It is the aforementioned works, those bejeweled with so many visuals, that we need to examine first in order to better understand other, more spartan pictures by Wagner.

By the time we come to her hospital imagery, we are still somewhat ill-prepared for the minimalistic tableaus presented to us. Indeed, little, if anything, can prompt us for the jarring visions of the wholesale loss of civil liberties—personal violations that, sadly, regularly occur in Western hospitals and treatment facilities. Chemical restraints are often met with physical restraints in what can only be described as a medical torture chamber.

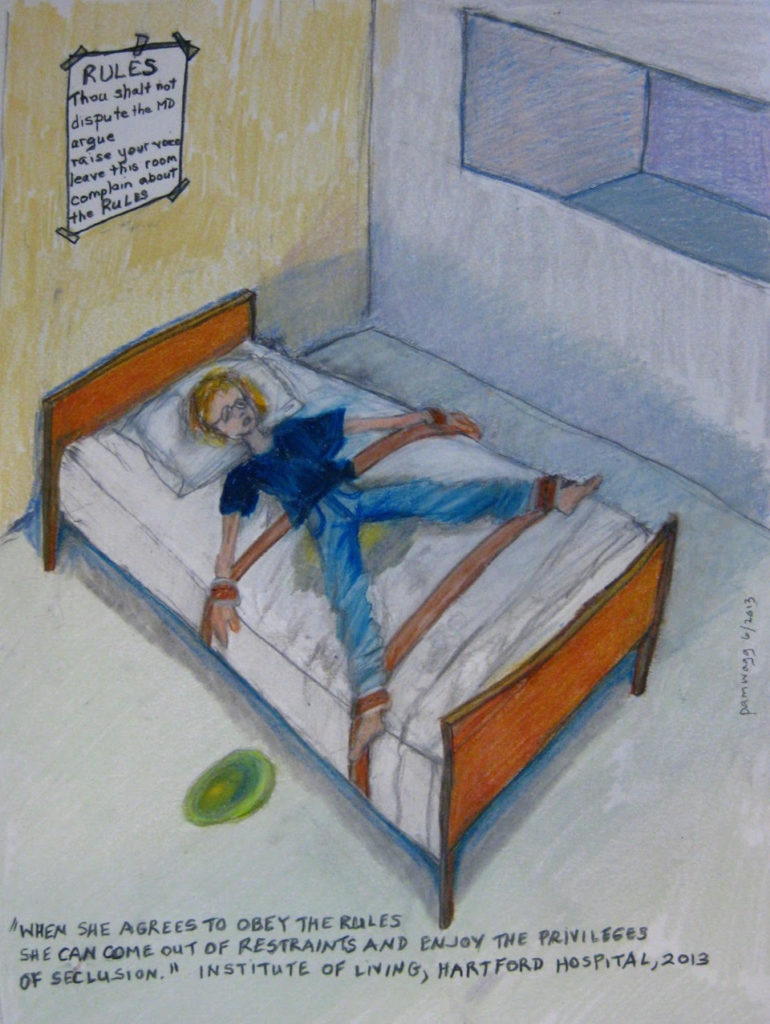

In 4-point Restraints for Breaking the Rules at IOL presents such a dilemma. The patient is the lone figure in the room, splayed out over a soiled bed. Her hands and feet are locked into restraining belts. She is alone, vulnerable, and completely at the mercy of a not-so-neutral hospital staff.

The “writing on the wall” belies its “authority” and suggests that the use of restraints was uncalled for, as over a trifle rather than a mountain. Ancient Hebrew script is invoked with a dominating “command”: thou shalt not dispute the MD or even complain about the rules. We are given a power dynamic that is highly askew, one that should be quite bothersome to most any viewer’s conscience. Why must the degrading techniques be used? Where is the all-seeing “eye of wisdom” ever-present in her other works? How is justice in any way served by such an egregious lack of personal autonomy? Why the added trauma for someone already in distress? (Never mind ethics or oversight, just obey.)

“Seclusion” is suggested as a “reward” for the patient if she obeys the paternalistic, patronizing rules. Perhaps a notch better than restraints, it is yet not a situation one would wish upon anyone else. We see a glimpse of this suffering in her Ice Hospital. Here, the eye has even less to go on—we are cornered into the two joining walls, along with the sitter.

Wagner wrote that she has spent long blocks of time in seclusion—e.g., six weeks—and that, at one hospital, patients were regularly denied clothes, phone calls, visitors, or mail—conditions she calls “useless and cruel,” particularly since she herself needs such distractions in order to quell the voices.10

Unlike so many female nudes in the history of art, the main figure in Ice Hospital appears not as a symbol of beauty but of institutional betrayal. The monochrome tones and haunting mood might recall such realist painters as Edward Hopper, known for making the idea of loneliness into a solid visual fact. But if there is a mild ennui present in his Morning Sun (1952), it is relieved by the presence of the natural light and physical beauty of the sitter. There is a window with a view. Ice Hospital is absent of such transcendent light—any suggestion of illumination here is but the slightest glow of what surely is artificial light. (Psychiatric patients are often not let outside.)

We understand that the individual is not only violated (as naked, not nude) but cold, shivering—and her pose represents all she can do to keep warm. It is a marked contrast to Hopper’s poised figures. There is little here in terms of self-defense against the elements, not even a blanket—and Wagner’s figure becomes one with the chromatically cool colors of the hospital wall and floor. Head down, she does not return our gaze.

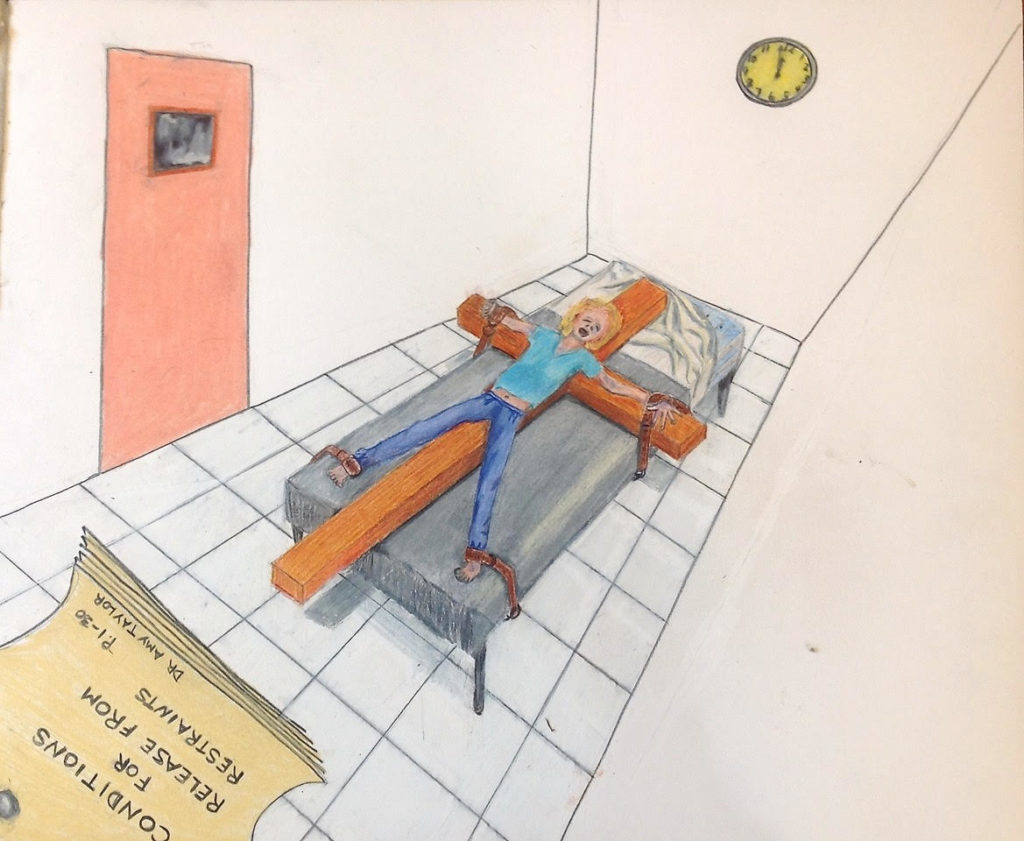

Crucified #1 presents us with charged emotion and a sense of psychological urgency. A figure, seen crying out, is laid atop a cross on a hospital bed, with restraining belts where traditional crucifixion spikes would be. She is being crucified, it seems, but not by nails: the very instruments of hospital “treatment” are being indicted in what becomes something akin to a capital punishment.

It is a keen, succinct synthesis of historical religious painting, modern death penalty imagery, and socially engaged art depicting captive populations. Van Gogh’s paintings of the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole at St. Rémy are important precedents, and his forced perspective and heightened colors are significant for us here, too.

The intense mood in Wagner’s Crucified #1 is not conveyed so much through color, though, but its absence—bare white walls, one with a clock just about to strike midnight, the proverbial “last minute.” Again, we find some script: this time it confronts us in the left-hand corner—it impedes the eye’s easy escape from the unit. They are “conditions for release,” but they hardly seem as important as the main action: Why is someone being effectively tortured in a hospital? What (little) was actually done to deserve a punishment so severe? Who wouldn’t cry out in horror in such a situation (and thereby violate the myopic, sadistic “terms”)? Why the legalese for an innocent victim? It matters not—door closed and presumably locked, there is no way out of this white martyrdom.

Wagner once wrote of others what might be fittingly said of her figure here: “Whatsoever you do unto the least of these, you do unto me.”11 Furthermore, we do well to acknowledge that both psychosis and deep spiritual connection can foster the notion that “you yourself [are] God”—something that isn’t interpreted by medical doctors, which therefore must be “treated, medicated, controlled”.12

Such difficult, inconvenient truths about the realities of interventional psychiatry are further made evident in Michael E Balkunas MD Giving Shot of Haldol to Terrified Psychiatric Patient. This piece happens to have a notable precedent in modern art. In 1922, the German artist Otto Dix painted clinical psychologist Dr. Heinrich Stadelmann in clashing and garish tones. Green wars against a backdrop of red and orange in the picture. The figure’s face is not normal flesh; the colors are skewed. It looks like a cross between neon lighting and jaundice—the fantastical eyes are yellowed, and his face is glowing in an abnormal way. He appears far more psychotic than any individual he might treat.

Similarly, Wagner’s Balkunas is presented as “mad”: the eyebrows are pitched, the forehead is furrowed, and the eyes are beady red. Purple drool stems from either corner of his mouth. He seems intent only on his terrible injection and lacks all humanity. The exaggerated size of the doctor shows his “importance” in what is known in art as hierarchy of scale. The patient puts a hand up, but it is futile. His or her fate seems, instead, to be spelled out by the restraining bed in the background. An array of onlookers completes the scene—a somewhat judgmental looking group, aiming only to satisfy their visual curiosities rather than be of any serious “help”.

Such was the reality for Wagner and for so many others who have suffered at the hands of the powerfully complacent. Her actions here as artist—in contrast to patient—is the one modality that restores agency to an otherwise unwilling subject. It is nearly Shakespearean:

“And all lingers even so beyond the power of words … and the mirror repeats the visible world.”13

Thank you for introducing us to Sparrow Wagner and her work. I find every pice to be moving in their own ways, but there’s just something about “Ice Hospital” that hits a nerve for me.

It’s ridiculous that all of this torture is committed in the name of “treatment.” And it’s even more ridiculous that most people who’ve never been in a psych ward buy into the lie that everything is peachy keen behind closed doors and that “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” is nothing but fiction and that conditions within the wards are *so* much better today. They just refuse to understand that it isn’t treatment — it’s incarceration.

Report comment

Ice hospital which is actually titled Self Portrait in Seclusion, is shown in my third book, LEARNING TO SEE IN THREE DIMENSIONS, (Green Writers Press, 2017) along with the poem, “Ice Hospital“, in the section, Poems in Which I Speak Frankly…this book has many of my artworks in it, which accompany the poems. Just letting you know.

Phoebe

Report comment

Have these works been shown in an Art Show, Gallery? If so, where?

Report comment

I understand that Wagner’s art has been shown locally. In particular, Hooker-Dunham and Gallery at the River Garden.

Report comment

Larry, would this gallery be in Vermont or in California? Thank you for the critique. Hall’s Dictionary on Subjects and Symbols in Art, the author suggests the Bell. “Attribute of Antony the Great, sometimes attached to crutch or staff; of Music, personified, one of the Seven Liberal Arts, who strikes a row of bells with a hammer, as does David in medieval Psalters. Thoughts about being Music Personified? Democracy, that rings out from a cracked bell or Buddhist Bowls? To make sense or understand, the nature of the industry by which the pharma began to shape the space marked for anything but healing, seemingly needs to realize now a voice, gained by shows. How to realize shows? On this topic? That conveys the problem is not all within the individual, but in the very practice of what is considered treatment?

Also, with regards to entering into the High Holies, by which Time becomes warped, the pace becomes slowed down, as reflexivity goes up? How or do you see that in your critique and gaze, as in scaling of relationships, and then where does this point, if point describes adequately, realize meaning within the individual and also the technology?

There is an incredible amount of information being shared on this site, and then learning how to respond, raise some questions, or even choose to be silent. Though to muster up, a way to realize an appropriate intervention requires a skillset of held by a team. Thank you for the sharing your insights.

Report comment

These shows were in Vermont, in Brattleboro. But none are currently in planning, alas. And no Gallery has indicated interest.

Phoebe

Report comment

I suspect we we will have to create the gallery!

Would that be of interest? When our 501.c3 was intact, I would invite the local Mayor, Jerry Abramson, to be a judge for our Art Show. He had endured handling the mass killing at the newspaper by a man on Prozac. The settlement by Lilly silenced the discussion.

But for 3 days we had a conference, presentations by our people in what was then the Holiday Inn on Broadway. Part of the disconnect that would frustrate the efforts was the discounting, that seemingly conveyed or ignored that We, are the citizens!

Your work is remarkable and elevates the dynamic that so many face when being processed through the institution. Advise as you see fit, for I do believe the creative way forward, through the Arts will lift and communicate the reason to affirm creatives.

My brushes and pencils are smarter than me! The keyboard, I wonder whether to take this apart, and strap down to the bed… (which I would experience after walking off the grounds, and being taken back to the hospital, and placed in seclusion).

tks much!.

Report comment

Vermont. I will be reflecting on your other comments. There is a dearth of attention to this topic, not simply in psychiatry but also in visual art. We could certainly use more shows and publications from a critical perspective. I think there is great value in seeing these problems, as that doesn’t allow for them to be rationalized away.

Report comment

Larry that would be great! So few people see our art work and I think that’s a shame. You can see from the comments that many MANY of us work out these traumas thru art of some sort. It’s about time that we were taken seriously as artists, all of us, and also as experienced commentators on a subject that so few know enough about to become concerned.

Report comment

Thanks for so eloquently describing Phoebe’s art, Larry. I’ve got an entire series of works visually describing psychiatry’s iatrogenic “bipolar epidemic.” I’m working on my “The Great Escape” piece right now, with the DSM “bible” thumpers painted as the clowns that they are, in their clown cart. It’s a Chagall inspired piece based upon his painting called “The War.”

Let’s hope our art history books some day will include the works of the psychiatrically defamed artists, the Spirit led, anti-child abuse artists – not just include the “Spirit cooking” and pedophile art, which is all the rage with the so called “elite” today. Especially since the psychological and psychiatric industries are so systemically and regularly targeting, and attacking, the artists.

After a recent show of my work, a psychologist claimed to want to give me an “artist of the year” award. Then he claimed he wanted to become my “artist manager.” But then he handed me a classic thievery contract, under the guise of an “artist manager” contract. Proving that all that psychologist/artist wanted to do was to steal all profits from my work, my work, my money, my story, etc.

Oops! my work was “too truthful” for that Lutheran psychologist, probably would be for other “mental health” workers, too. I’m quite certain that certain psychologists and psychiatrists don’t want the crimes they’ve been perpetrating in private for so long to be exposed to the public.

But I think someone should remind the mental health industries that “a picture paints a thousand words,” thus the visual artists have a powerful communication tool. Therefore, systemic attacks on artists might not be the wisest behavior.

Thanks for sharing your work, Phoebe. It’s very descriptive of the abuses of psychiatry. My work shares a lot of the same imagery … upside down and backwards American flag, minute to midnight, lots of eyes, psychiatric defamation and neurotoxic poisoning as a modern day form of crucifying people. I also use “The Scream” image a lot, to represent my psychotomimetic “voices.” Are you familiar with the story behind that painting?

http://totallyhistory.com/the-scream/

Artists paint the human experience. My psychiatrists and psychologists wanted to medicate, and deny or eliminate, the human experience.

Report comment

You’re most welcome. If you wanted to discuss your own work further, you could ask at MIA to put us in touch directly.

Report comment

“After a recent show of my work, a psychologist claimed to want to give me an “artist of the year” award. Then he claimed he wanted to become my “artist manager.” But then he handed me a classic thievery contract, under the guise of an “artist manager” contract. Proving that all that psychologist/artist wanted to do was to steal all profits from my work, my work, my money, my story, etc.”

Yes indeed shysters every where. Both Rockefeller(eugenics) and Sackler (psychiatrists psych and opiod drug mass slaughters) are major funders to the cream of the art world – major shame on the art world. So what backs the institutions that artists aspire to are the major world drug dealing and eugenic monsters and evil shysters of all time. So we can only conclude – f*ck the art world, along with the shysters who fund them. The truth will not be found in the big dealer gallery and major museums. The artists they show are pets who are about as challenging as a gnats co*k. Bacons self portrait was recently found on a psych rag. He was not ‘mentally ill’ as the text tried to make out – it was front cover art psych diagnosis which is ofcourse bullcrap.

Report comment

Yes, how does an ethical artist succeed when the entire art industry has been taken over by drug dealers, satanic “Spirit cooking” and pedophile art proponents?

And the mainstream religions, who should be supporting the arts, hypocritically claim to be supporters of the arts, but do the antithesis, at least when it comes to the visual artists. Because they, too, have been bought out by the systemic child abuse covering up “mental health” systems.

Have you read the communist manifesto? The satanic takeover of the art world, religions, and unquestioning trust in psychiatry are all on that manifesto. It was all pre-planned.

Oh well, someone needs to be visually documenting the truth / systemic attempted destruction of America from within. But merely doing that makes my “too truthful” art so insanely controversial that it turns a child abuse covering up Lutheran psychologist into a “paranoid” “shyster,” who wants to steal all my work and money.

Not sure what to do, but pray all will be judged fairly by God, and that God – and his true followers – win. “For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.”

Report comment

Thanks for this article Larry (and thank you to Ms Wagner for the wonderful works depicting some truths about what has been wrongly called ‘health care’). It reminded me of many images of places like Abu Ghraib and Don Dale detention centre where Dylan Voller was ‘incarcerated’ (google “dylan voller detention” and look at the images tab).

I noticed in the footnotes

Pamela Spiro Wagner and Carolyn S. Spiro, M.D., Divided Minds: Twin Sisters and Their Journey Through Schizophrenia.

Ms Wagners’ twin sister is a doctor? If so, I wonder how she feels about the ‘treatment’ documented in these pieces?

And I wonder about the size of the works and media used by the artist.

Report comment

Hi Boans,

Phoebe here, the former pamela of the book Divided Minds etc.

My twin sister died in February of 2019, but I know that as late as 2016, when she ended all contact with me, something that had started as early as 2009 with her second marriage, she believed in restraints and seclusion and thought such control measures were justified and harmless to the patient. When she was an inpatient psychiatrist at the YPI at Yale, she used to tell me how they taught patients there to ASK to be restrained…which struck me then as now as teaching an abused child to ask for punishment as an indication that his or her parents care or even love them. It struck me as a horrendous solution to a problem that should not exist, and would not, if we stopped feeling that “mental patients” need to be controlled…One of my pieces, called Psychiatrie Macht Frei or “Fork you, Psychiatry” depicts a victim of Abu Ghraib torture in it, as it depicts psychiatric tortures and show a big third finger to it all. You can see this work, which accompanies the poem “Tyrannosaurus rex” and others in my third book LEARNING TO SEE IN THREE DIMENSIONS, (Green Writer Press, 2017) or if you can find me on the internet or my blog, I will point you to this work, as I cannot post it here. Best wishes,

Phoebe Sparrow Wagner

Report comment

Perhaps there is a way to explore, or I am curious if you embrace an awareness for the Fourth Dimension? Attempted to convey this aspect in the final show, while hanging on by a thread.

I would experience in junior high, the student who would ask for punishment from the industrial arts class. The idea was bizarre, but even more where the other teacher, Bryant would give all his students a Christmas spank with the paddle. Sick educational systems!

Your statement about parental love is of importance…. For the opposite of love is not hate but indifference as Wiesel would claim. The triangulation and knowing how a developing human processes the emotions when the experiences in an hospital setting are saying “Fuck You, Psychiatry, Psychiatrists and the Hospital” (see Artuad’s comments), then the platform to connect and change the parts in the systems become crystal clear…….. at least that is what the thinking is saying now.

Report comment

Thanks for the reply Phoebe.

I must admit I did wonder if your sister was a psychiatrist. I think I prefer that my brother was a patch wearing member of an Outlaw Motorcycle Gang lol.

Seriously though. My own journey lead me to pondering the pictures from Abu Ghraib and wondering about why these acts were NOT considered acts of torture. And the question always came to me “what is it that has allowed these people to survive these vile acts”. And the only answer that I could come up with was their faith.

Then it was all done to me. And what came out of that was that acts of torture can be easily concealed via the use of the provisions of the Mental Health Act. They tortured and kidnapped me (according to strict black letter law) and then tried to make me into a “patient” post hoc. I’ve written much about what occurred after that here. Whilst my claim that they tried to snuff me might sound paranoid without proof or a motive, they failed to retrieve the documents to ‘cover up’ the torture and kidnapping and thus my claim MAY be true. I accept that it may not be, but the way the matter has been dealt with by the State tells a sorry tale. If the only way these matters can not be crimes is by police negligence and refusal to act on what they know are criminal acts, while doctor sorts it out with an overdose in the ED, then I am not living in the place I thought I was. Good news (for me, not so much for the people who thought they had retrieved the proof of the crimes, and snuffed out the complainant and threatened all witnesses) someone was watching, and interrupted the unintended negative outcome. And this brings me to the reference to the National Socialists in Germany. We could hardly imagine them prosecuting the likes of Mengele if he arranged to have a Torah placed under the pillow of one of his critics (non Jewish) and then called the SS to have them ‘detained for assessment’.

‘Treat’ them and then make them into Jew with fraudulent paperwork post hoc. And of course in that environment, what would be done if the State found out? Pretty much the same as has been done here with my case. We can’t hold the people who are doing the nasty for the state to account, that would be self defeating. So they feel a need to conceal the acts of torture and kidnapping for these criminals because …… the claim is not in the public interest to bring the torturers before the courts. Though I wonder if the public were aware of this that they would agree. We will never know because the media AND advocates remain silent on the matter. And I assume for the same reasons that the newspapers in Germany did.

“One of my pieces, called Psychiatrie Macht Frei or “Fork you, Psychiatry” depicts a victim of Abu Ghraib torture in it, as it depicts psychiatric tortures and show a big third finger to it all.”

It was a theme in a mural that I painted on a wall in my home after I was tortured and kidnapped, the Gates of Auschwitz, my ‘sins’ surrounded by razor wire to deny me even the temptation. The scene in Clockwork Orange where the Priest says “But the boy has no choice, he has no free will to choose” after he has been treated using the Ludovico Technique.

And of course any legal representative would not see these treatments as “torture” because they know that the Convention against the use of Torture contains the words in Article 1 that it is NOT torture if it is “inherent in, or incidental to lawful sanction”. Something easily overcome by procuring a police referral (though this is also a criminal offence in my State) and then your free to torture away, and those charged with protecting the public (the Chief Psychiatrist) will deny any legal protections and maintain any fraudulent lies manufactured by the hospital to conceal their misconduct and torture. And how easily that is done would positively frighten the public (I note that our Treasurer fled the State rather than be referred to mental health services by police. I assume he was ‘in the know’ where others are being kept in the dark regarding the arbitrary detentions, and use of known torture methods [‘spikings’ with intoxicants before interrogations, and then slandering should one complain]).

They need to maintain a certain level of fear in the community, and it must be quite a balancing act. Openly torturing people wouldn’t be accepted, but they need to do it, and then let people know there is no remedy when they do (thus they remain silent for fear of being next). I’m sure the public gets the picture with psychiatry. We all seem to be well aware we are heading down that path again in recent times, though no one prepared to speak up and try and stop the Juggernaught of National Socialism. Three generations of imbeciles is enough according to Oliver Wendell Holmes lol

I do like your work, and I hope that some day it will stand alongside the work of people like Viktor Frankl (Mans Search for Meaning) as a testament to what certain people in our ‘democratic’ societies have been subjected to. Yes it is tragic what has happened, and for me with my beliefs God will give fair warning, and then the trumpet will be sounded.

And the question regarding the media you work with? Do you paint. If I were not so damaged by what has been done to me, they could have had 9 years quality work out of me now. Still, they have not only money, but humans to burn in my State. One big party, and psychiatry is keeping the pub open way after hours lol

Please keep documenting the truth for all to see. And if you have time google Dylan Voller incarceration and have a look at how we treat children in this country. The similarity to your work is striking. I wonder how I would view the world had I been treated in such a manner as an 8 year old boy.

I hope to be in touch soon.

Report comment

Hi Boans,

It does seem as if Australia is one step worse than the USA in terms of how it treats so called mental patients… the dylan voller case is one example but there are also others as you know. Patients kept in restraints almost continuously for months at a time…that used to happen here too, in the 60s and before. And I’d say a lot still happens, including the near murders (and murders even) of which you were a victim, and I myself too. I remember vividly three times that happened, and in the last incident (in 2014) two security guards at the hospital had stripped me naked and four-pointed me spread eagled to a bed, then with a towel one of them muzzled my face and pressed down so I could not breathe, while the nurse injected me with their usual three punishment drugs. I thought I would die, and I know he did it on purpose because he said, Serves you right, after he took off the towel and let me breathe. It’s hard to remember things like this…

I paint, I draw, I make large papier mâché sculptures, I do a lot of everything in art as it keeps me alive. I didn’t start doing art till I was 55 and I’m 68 (almost) now so it feels like I’m making up for lost time. The pieces here were all very early ones, but I keep learning and growing.

Best wishes,

Phoebe

Report comment

Yes Phoebe, Australia does seem to fit into the category of “worse”, one step, maybe two. It does of course provide opportunities for those who wish to conduct experiments that would not get past ethics committees to come here and corrupt our systems and make advances in medicine.

I was surprised when I head about the conduct of the guards at Abu Ghraib as I was reminded of the findings of the Royal Commission into Police conduct which described the methods being suggested as possible ‘coercive methods’ that did not constitute torture had been used here for many years already. I don’t know that cattle prods have been sanctioned in Abu Ghraib or Guantanamo but …… certainly this method of extracting confessions was documented in the report (along with the chapter on the Corrupt Practice of ‘Verballing’, which I have since found out is standard practice for mental health professionals. Might explain the continual state of crisis they are in, corruption will of course get worse until someone has the courage to deal with it. And I can’t see that being anyone at the MH Commission which seems to be a posting for reasons other than choice).

I can’t begin to imagine what such ‘treatment’ does to your ability to trust. I know that I still to this day suffer from a form of anxiety that I had never experienced until the day I was snatched from my bed. And it really amazes me that these people simply don’t even see what they have become. Though the good news about that is they don’t see.

I can’t tell what ‘humanity’ or compassion looks like, but I do know what the lack of it looks like. I think you captured it in the eyes of Dr Balkunas. I know that I saw it in the eyes of Dr “I’m the Boss around here” just before he was rudely interrupted. It seems he was wrong, because he nearly wet his pants when told that he was required for a “word, NOW”. How on earth was he going to conceal his psychosis from two such eminent doctors? Right in the middle of snuffing a patient, and they want to talk NOW? “I just…. just need to do this” mmmmm maybe not Doc. It’s a Rat Trap, and you been caught lol.

Take care Phoebe and once again, thank you. You give me hope for the future when people begin to realise what is being done over the razor wire fence….. again. I understand those that are desensitized to their brutality, and it is only when others from outside are shocked by what they see that it starts to sink in what it is they have been doing. like Michael Douglas in Falling Down, “you mean, I’m the Bad Guy?. When did that happen.”. It happened the first time they thought, it’s okay, no one is watching.

Report comment

Phoebe – your work is very good. It is a powerful example of and contrast to a system which is very bad.

You say more with your art about the torture of psychiatry than many of us could ever briefly describe in words.

You are an inspiration. Thank you.

Report comment

This is EXACTLY why ART (and its review/critique) exist. Thank you both.

If Phoebe reads this, do you allow your images to be posted on other websites if your work is referenced/linked? There may be philosophical differences here and there, but I would love to include them somehow.

My website http://www.evanhaarbauer.com deals with a number of related/semi-related issues, informational and musical/poetic. I’m still updating, editing, and remixing.

Report comment

Hi Evan

Absolutely you can share my images with credit. There are many more at my blog as well. http://phoebesparrowwagner.com

Just do a search there on restraints, seclusion or hospital torture Art and you should get an eyeful!

Best wishes

Phoebe

Report comment

hi! Such a pleasure to see Phiebe’s work on this website.

as i am unfirtunately to understand and to make sense of all emotional overwhelm it evolves from a traumatic loss of one kind or another.

i of course in regression to my own childhood can relate to a lost childhood in mant respects.

i am so glad pheob’s wonderful accounts of her experiences with detention in psychiatry she has expressed in art in her wonderful way are on this site and i hope she continues working through her life.

thank you!

Report comment