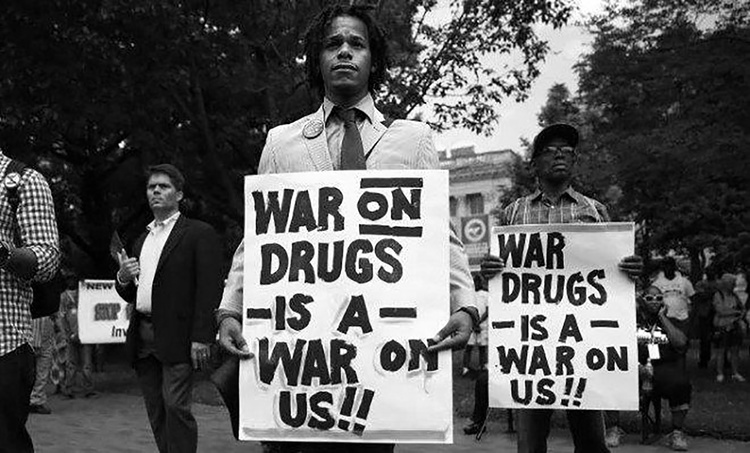

Research evidence suggests that the criminalization of drug use and possession has roots in explicit racism and reinforces inequality. A broad coalition of professionals writing in the American Journal of Bioethics seeks to rectify the havoc wrought by the War on Drugs on racialized communities. The coalition calls for evidence-based and ethical new policies, including the immediate decriminalization and regulation of recreational drugs, expunging nonviolent convictions related to small quantity possessions, and the release of prisoners serving time for similar offenses.

The moral model of substance use implicit in the War on Drugs in America has made it difficult to replace the stigma associated with substance abuse and addictive disorders with more accurate and humane frameworks. Such frameworks take social context and identity into account, which is a useful way to address the complex interrelations and impacts of race, discrimination, poverty, and mental health on drug use.

Nevertheless, the moral framework for understanding drug use across the lifespan is enshrined in the War on Drugs’ punitive policies. There are signs of hope for decriminalization programs in states like Oregon. Still, professionals in fields related to substance-use disorders call for the War on Drugs to end more immediately.

Bioethicists and scientists from Yale University, Dublin City University, and Columbia University reviewed the literature on the disproportionate targeting of Black Americans for drug-related crimes and other failings. They argue that drug prohibition and criminalization ultimately harms users and non-users alike and imposes many health-related costs.

The authors detail the societal costs related to drug prohibition and criminalization, including its “criminogenic” effects, where drugs’ illegal status leads to other crimes to obtain and purchase drugs. They also review the impoverishing and demoralizing effects the prison system has on drug users and the communities they belong to and how illicit markets tend to increase the harmfulness of drugs.

The cost of drug policies related to public health is also inordinately high, leading to unsafe use of drugs and inadequate knowledge about them–even their therapeutic effects. It also throws up barriers to treatment for substance-abuse disorders, diverting funds from creating health and safety regulations.

Tying these together is the overall failure of drug laws, following biomedical and disease models of addiction, to respect the contexts of users or would-be users. These usually involve economic deprivation and vulnerability to structural exploitation like increased police presence, higher conviction rates, and harsher sentences. The racial injustices related to drug prohibition are also found in countries like England and Wales.

To address these, the coalition calls for criminal convictions for nonviolent offenses pertaining to drug use or possession of small quantities of non-medical drugs to be expunged, and for those currently serving time for these specific offenses, including those with drug-related parole and probation revocations, to be released.

Moreover, outright prohibition conflicts with one’s right to control one’s body and the substances that go in it, whether for enjoyment or self-exploration. These rights do not, on principle, violate the equal liberty of others.

The bioethicists explain that decriminalizing drugs does not at all undermine public health or safety, but in fact, enhances it by making drugs safer and eliminating the injustices associated with the arrests and incarcerations of drug users, freeing up resources in the criminal justice system and lowering rates of drug abuse and related health problems. Citing Portugal’s successful decriminalization policy, they write:

“When drug users do not fear criminal charges, they are able to seek out medical treatment, mental health care, and social support programs, and can access government-approved public information about the harms involved in drug use. In Portugal, the social institutions that focused on harm reduction instead of punishment were also able to engage and help more young people than the criminal system.”

The authors suggest going even further, recommending legalization and regulation to eliminate the harms of illicit markets and the knock-on effects faced by drug users in their reckonings with the legal system over civil penalties.

Legal regulation offers several other advantages over decriminalization, like allowing governments to introduce “safe supply” programs for currently illegal drugs. These programs raise the safety and quality of drugs, reduce stigmatization of drugs and users, and increased knowledge that supports best practices for use.

Implementation is key here, as the benefits of legalization rely on the rigor of protective policies and their enforcement. The authors acknowledge that these changes won’t come easy under the UN’s international drug control treaties. They are nevertheless optimistic about the United States’ ability for leadership in this area,

The ideas regarding decriminalization, as a step toward legalization and regulation, have received near-total consensus amongst former drug user groups, policy experts, harm reduction advocates, and criminal justice reformers. The costly and ineffective War on Drugs in the US has disproportionately targeted Black and Hispanic communities. Decriminalization should be the first step, followed by specific support programs for these communities.

****

Earp, B. D., Lewis, J., Hart, C. L., & with Bioethicists and Allied Professionals for Drug Policy Reform. (, 2021). Racial Justice Requires Ending the War on Drugs. The American Journal of Bioethics, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2020.1861364 (Link)

This is the classic liberty-based argument for decriminalizing certain “victimless” behaviors.

Posed as a personal rights issue, decriminalization garners support from liberal-leaning people.

The argument against such changes usually focuses on how they are perceived as normalizing these behaviors, even though they are known to pose significant risks to “misbehavers” and the people around them.

This conflict of ideas creates a major quandary to people like myself who recognize the harms committed by our law enforcement system but do not wish to see the mass normalization of dangerous behaviors. Where does such a trend end? Long ago, premarital sex was normalized. Now we have normalized the use of harmful psychiatric drugs, as well as marijuana. What dangerous behavior will be next? Vandalism? Robbery?

Furthermore, I don’t want to see drug use in particular normalized, and this is definitely the goal of the drug companies, at least regarding “mental health” drugs. I believe the drug company overlords would welcome an increase of all drugs, and would take advantage of the opportunity to market more drugs to the population for “recreational” purposes.

Calls for decriminalization and leniency seem insincere to me when they focus on turning those committing unwanted behaviors into victims and those wishing to improve behavior into oppressors.

What I believe is closer to the truth is that populations have been convinced that the only way to guard against misbehavior in their communities is by use of a punishment-based system involving laws, law enforcers, a judicial system, and various forms of punishment. This system has proven to be ineffective. It is in fact based on a criminal control paradigm. But this doesn’t change the fact that a majority of people in a majority of communities want to reduce unwanted behaviors, not increase them. And normalization of such behaviors, particularly when accompanied by Corporate marketing campaigns aimed at encouraging such behaviors, tends to result in an increase in the unwanted behaviors.

Cigarette smoking is a classic case of society rising up to de-normalize an unwanted behavior. Through a strident marketing campaign, the message got through, and smoking has lessened, though it did not end by any means.

Conversely, normalizing behaviors that were unwanted signals that those behaviors are no longer unwanted. A consumer market is created, which Corporate then promotes to, usually leading to increases in those behaviors. This has happened with premarital sex, psych drugs, and more recently with marijuana.

What society needs, then, is a more effective system of controlling unwanted (destructive) behaviors that empowers individuals to make better life decisions rather than delivering up to Corporate new audiences to be marketed to and controlled. This is the societal struggle we see playing out all around us right now. Do we really want Corporate to save us all with more legalized but very dangerous drugs? Or do we want to find structures that will actually help us build saner communities?

Report comment

It’s largely semantics, as the “war on drugs” has always been in fact a war on Black and poor youth (enthusiastically championed by Biden AND Nixon prior to Biden becoming “woke”).

In any event, let’s finish off the phony war on street drugs and amp up the one on psychiatric neurotoxins. (I’m wondering, if we could morph this term to “psychotoxins” would it enter the street vernacular and thus be more a subject of mass contemplation?)

Report comment

As a smoker, who didn’t know the legal activity of smoking cigarettes, was considered illegal, to my “bad fix” on a broken ankle covering up, paranoid of a non-existent malpractice suit, and child abuse covering up, doctors, according to my child’s medical records.

Who disingenuously prescribed me a “safe smoking cessation med” (actual dangerous antidepressant) and a “safe pain killer” (actual “dirty opioid”). Then misdiagnosed the common symptoms of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome as “bipolar.” After that PCP had unwisely and abruptly taken me off the antidepressant.

I think we do need to end the “war on drugs.” Since the doctors are mass prescribing mind altering drugs to people, to cover up their malpractice, for legal – albeit not wise – drug use, while lying about their crimes.

No doubt, the doctors have been given way too much power, and it’s a shame when doctors now claim to know nothing about the common adverse effects of the drugs they prescribe. When it is now known by many, that both the antidepressants and antipsychotics (aka neuroleptics) can create “mania” and “psychosis,” via anticholinergic toxidrome.

Which all the doctors are taught in medical school, but is not mentioned in the “mental health” workers’ DSM5 “bible,” any longer. And the antipsychotics can also create the negative symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome.

I don’t know that all drugs should be legalized, but I do believe pot should be, and maybe others. But I do believe the antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzos, and opioids should be weaned out of legalized use, by the doctors.

Or, at least, the benzos and opioids should only be given to older, “chronic” patients. But most definitely NOT those of us who are young and healthy, who’d dealt with prior easily recognized malpractice, merely because a scum bucket PCP wants to cover up her husband’s “bad fix” on my broken ankle.

Report comment

Or, at least, the benzos and opioids should only be given to older, “chronic” patients.

WHAT? Sounds like ageism, am I missing something? Plus we already have COVID to kill off the old people and useless eaters.

Report comment