Editor’s Note: Over the next several months, Mad in America is publishing a serialized version of Peter Gøtzsche’s book, Mental Health Survival Kit and Withdrawal from Psychiatric Drugs. In this blog, he gives practical advice on how to taper off of psychiatric drugs. Each Monday, a new section of the book is published, and all chapters are archived here.

Tips about withdrawal

Anders has assembled a consecutive cohort of 30 patients who contacted us for help. We set no limitations on drug type, diagnosis, duration of drug intake, current symptom severity, previous withdrawal attempts, or the treating psychiatrist’s assessment of whether discontinuation could be recommended.

About half of the 30 patients had been on drugs for 15 years or more; most of them had tried to withdraw several times without success; and all types of psychiatric drugs were involved. Despite the high odds, Anders has come a long way and has withdrawn most of the patients, in his spare time and without pay.

Anders’ work is impressive, and his patients are immensely grateful for his altruistic help. They make ad hoc appointments for consultations with him according to their needs, and he arranges group gatherings four times a year where they share their experiences. They have his mobile number and can call him at any time. This is important psychologically and has put an extra burden on him. Many have used this possibility, which illustrates that it is demanding to help people withdraw.

The patients fill out three questionnaires:

- A qualitative structured interview before the first dose reduction, which includes their history and experience with psychiatry, details on previous withdrawal attempts, their own views on their symptoms and condition, details about what they have been told by their psychiatrists, and fears and hopes for the planned withdrawal attempt.

- A qualitative interview after having become drug-free about their experiences of going through withdrawal and recovering from psychopathology, suggested guidance for other patients, what the barriers were, and what helped them specifically.

- A questionnaire on quality of life (Q-les-Q) before the first dose reduction and six months after having become drug-free.

Once a year, all patients and their nearest relatives are invited to an information evening where the basics of drug withdrawal and recovery from psychopathology are explained in detail and questions can be asked. The goal is to strengthen the relatives’ support function and to avoid having relatives who oppose the patients’ choice about withdrawing, which is often an issue.

A peer-support network has been established where patients can share information and support each other outside the official meetings.

The therapy involves helping the patients overcome the difficulties they experience. This includes handling withdrawal symptoms—what they are, how to minimize them, how to deal with them psychologically, and how to prevent them from developing into destructive anxiety and failure to withdraw. It also involves coping with anxiety and with the emotions as they come alive again (ceased emotional blunting), the return to society and social relationships, the crisis of realizing how much of one’s life biological psychiatry has stolen, and using genuine nondrug treatment of the condition if it is still present after successful withdrawal.

Without a systematic approach and support during withdrawal, the outcome is likely to be far less positive than what Anders has obtained. Of 250 adults with serious mental illness who wanted to stop psychiatric drugs, which 71% of them had taken for over nine years, only 54% met their goal of completely discontinuing one or more medications.32,33 They used various strategies to cope with withdrawal symptoms, which 54% rated as severe. Self-education and contact with friends and with others who had stopped, or reduced medications were most frequently cited as helpful.

Only 45% rated doctors as helpful during withdrawal; 16% began the process against their doctor’s advice, and 27% didn’t tell their doctor, stopped seeing the doctor, or saw a new doctor. Of the respondents who succeeded, 82% were satisfied with their decision.

In Holland, former patient Peter Groot and psychiatrist professor Jim van Os have taken a remarkable initiative. A Dutch pharmacy produces tapering strips, with smaller and smaller doses of the drug, making it easier to withdraw. Their results are also remarkable: In a group of 895 patients on depression pills, 62% had previously tried to withdraw without success, and 49% of these had experienced severe withdrawal symptoms (7 on a scale 1 to 7).33

After a median of only 56 days, 71% of the 895 patients had come off their drug. Each strip covers 28 days and patients can use one or more strips to regulate the rate of dose reduction. There is a website dedicated to this where updated information can be found: taperingstrip.org.

Venlafaxine can be a particularly difficult drug, but Groot and van Os showed that 90% of 810 patients who started on the lowest available dose, 37.5 mg, tapered off in three months or less.21 Some needed more than half a year, as they suffered from severe withdrawal symptoms, and many of those who succeeded in just three months would have benefitted from a longer period of withdrawal, as withdrawal symptoms can be markedly reduced if the taper takes over six months.34

However, there is an insurance problem. The Dutch health insurers refuse to reimburse tapering medication for so long because “there is no evidence in the literature” that such slow withdrawal is needed. The Dutch National Healthcare Institute has sided with the health insurers in all cases where patients have issued an official complaint, even when their doctors had attested to the severity of their withdrawal symptoms.21

- WARNING! Psychiatric drugs are addictive. Never stop them abruptly, because withdrawal reactions may consist of severe emotional and physical symptoms that can be dangerous and lead to suicide, violence, and homicide.6

- Never try to taper off a patient who doesn’t have a genuine wish of becoming drug-free. It won’t work.

- It is of utmost importance that YOU are in charge of the withdrawal. Don’t go faster than you can muster.

- Find someone who can follow you closely during withdrawal, as you might not notice yourself if you become irritable or restless, which are some of the danger signals.

- Withdrawal could be the worst experience of your life. You therefore need to be ready for it. You shouldn’t start if you are overworked or stressed, which could worsen the withdrawal symptoms.

- Always remember, particularly if it gets rough, that there is a drug-free life on the other side that is better, and which you deserve.

- It is not your fault if you feel miserable. It is your doctor’s fault who prescribed the drugs for you. Don’t lose hope or your self-confidence.

- Don’t believe doctors who tell you that you feel miserable because your disease has come back. This is very rarely the case. If the symptoms come quickly and you feel better within hours of increasing the dose again, it is because you have abstinence symptoms, not because your disease has come back.

In 2017, Sørensen, Rüdinger, Toft, and I wrote a short guide to psychiatric drug withdrawal, with tips about how to divide tablets and capsules, and made an abstinence chart. We updated the information in 2020 on my website, deadlymedicines.dk, where there is also a list of people from several countries who are willing to help people withdraw, and links to videos of our lectures on withdrawal in 2017.35

I will expand on this information below. I have been inspired by many people, in addition to numerous patients and the professionals already mentioned, particularly by psychiatrists Jens Frydenlund and Peter Breggin, whose book about psychiatric drug withdrawal is very useful.36

There is huge overlap in withdrawal symptoms between different drug classes, and although there are important differences, it is easier to follow the guidance if it is the same for all drugs. As it is highly variable what different people experience, even when they withdraw from the same drug, this also speaks for keeping the advice general. You may therefore use my advice if you are on neuroleptics, lithium, sedatives, sleeping pills, depression pills, speed-like drugs, or antiepileptics.

Before starting a withdrawal process, you must prepare very carefully. Make yourself familiar with the type of withdrawal symptoms, in the form of physical symptoms and unexpected feelings and thoughts, you may experience. Read the package insert for your drug and ensure you have good support from persons close to you. You must be determined to come off your drugs, as it might not be easy.

Withdrawal symptoms are positive, as they mean that your body is about to become normal again. They do not mean “me without drugs” but “me on my way out of drugs.” During a slow taper, withdrawal symptoms will disappear in most people after a few days or 1-2 weeks.

As already noted, withdrawal symptoms can suddenly reappear after a symptom-free period, e.g. if you become stressed.36 This is normal and does not mean your disease has come back.

It is important that you get a successful start. It is therefore often best to remove the most recently started drug,36 as withdrawal gets harder the longer you have been on a drug.33,36 It is also important to withdraw neuroleptics and lithium early on, as they cause so many harms.36 Withdrawal can cause sleeping problems, which is a good reason to remove sleep aids last.

It is not advisable to withdraw more than one drug at a time, as it makes it difficult to find out which drug causes the withdrawal symptoms.

It is rarely a good idea to substitute one drug for another, even if the new drug has a longer half-life and therefore would be expected to be easier to work with. Some doctors do this, but a switch can lead to withdrawal problems or the opposite, overdosing, as it is hard to know which doses should be used for the two drugs during the transition phase. But it may be necessary, e.g. if the tablet or capsule cannot be split (see below).

It is generally not advisable to introduce a new drug, e.g. a sleeping pill if the withdrawal symptoms make sleep difficult. If the troubles become unendurable, it is better to increase the dose a little before trying to reduce again, this time by a smaller amount or with longer intervals, or both. You decide, as you are in charge of your drug withdrawal; all others are your helpers.

How slow should you go? As most patients are considerably overdosed, it might be tempting to take a big step the first time and reduce the dose by 50%. But it is better to go slow from the start, not only because it makes you feel you can handle the withdrawal, but also because it can go wrong with a big first step. This could be because all drugs are nonspecific. They have effects on many receptors,34 and we don’t know the binding curves for all these receptors. Perhaps you are already on the steep part of the curve for one of the receptors when you start, or perhaps you are in particular regions of the brain.

Withdrawal is NOT an academic exercise that can be derived from theory or randomised trials; it is a trial-and-error process for every single patient. The pace depends on the drug, in particular on its half-life, which is how long it takes for the serum concentration to be halved. The variation from patient to patient is huge, also genetically, in terms of how quickly they metabolise a drug.

Anders found five randomised trials, but they are all problematic. Most importantly, the tapering was too fast in the tapering group, e.g. only two weeks. These trials have led to the erroneous claim that there would be no significant advantage of slow tapering compared to abrupt discontinuation!21

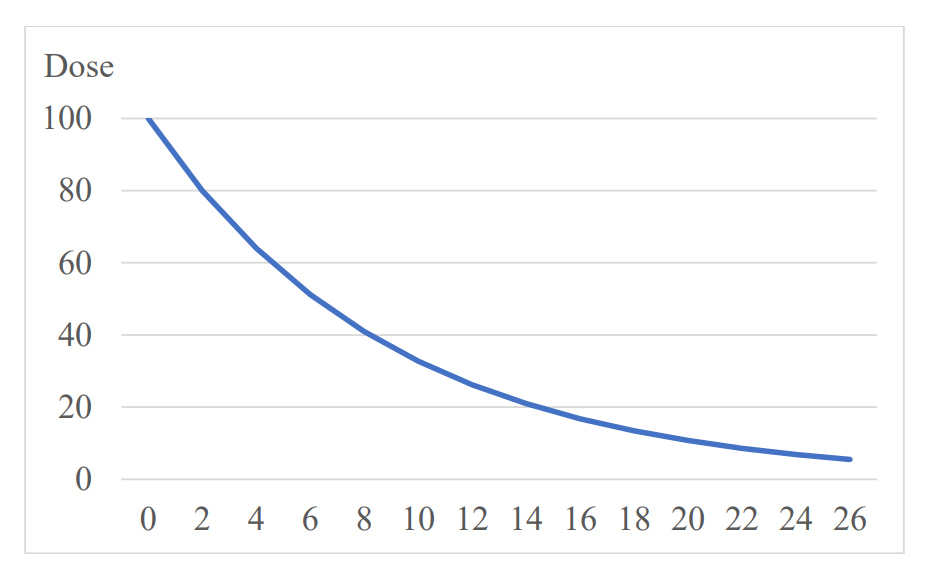

The dose reduction should follow a hyperbolic curve (see figure below). This sounds complicated but it isn’t. It just means that you reduce the dose every time you taper by removing the same percentage of your previous dose. Thus, if you reduce the dose by 20% each time, and you have come down to about 50%, then you should remove 20% again next time, which means that you now come down to 40% of the starting dose. You may need a nail file to do this and a scale so that you can weigh the amounts. Consult the pharmacy about dividing tablets or opening capsules; it sells a tablet divider.

The official recommendations are not like this. They may recommend you to halve the dose every time, which means that, starting with 100%, which is your usual dose, you go down to 50%, 25% and 12.5% of your usual dose in just three steps, which is much too fast. Using the percentage method instead, tapering 20% at a time, it will look like this after three steps: 100%, 80%, 64% and 51%.

You can try an interval of two weeks between dose reductions. If it works well, you may decrease this interval, e.g. to ten days. You might also need to go slower than 20%, as you might feel better by only reducing with 10% at a time, or you might need an interval of four weeks.34

The layperson withdrawal community has found that the least disruptive taper is when you reduce the dose by only 5-10% per month.23 However, if you reduce by 10% per month, it will take two years before you come down to 8% of your starting dose, so if you are on four drugs, it may take you eight years to become medicine-free. It is preferable to go faster than this, enduring what comes, and get a new life faster, also because the longer you take a drug, the greater the risk of permanent brain damage, and the harder it is to come off the drug.

Continue at your own speed—according to what you feel. Don’t reduce again before you feel stabilised on the previous dose. You may even want to pause on a given dose if you feel stressed. Try to be comfortable with what you do. If the withdrawal symptoms are bad, try to endure them a little longer, knowing that they will usually become less intensive rather quickly. If you endure the symptoms, it might give you an inner strength and belief that you can do it till the end and won’t fall back into the drug trap. But if it becomes too hard, go back on the previous dose and reduce the pace of withdrawal.

Always make sure you have one or two friends or family members with whom you can discuss your withdrawal and who can observe you. You might not notice if you have become irritable or restless, which can be symptoms of danger.

It is not uncommon that people don’t notice the progress they are making before very late in the process, and they might tend to focus on the unpleasant withdrawal symptoms. Be patient and endure it. Do something good for yourself. One day, you might suddenly notice the birds are singing, for the first time in years. Then you know you are on the right track towards healing.

The last small step can be the worst, not only because of physical issues but also for psychological reasons. You may ask yourself: “I have taken this pill for so long; dare I take the last small step? Who am I when I don’t take the pill?” It doesn’t help if your doctor laughs at you and tells you that it’s impossible that you can have any withdrawal symptoms when the dose is so low.37 If your doctor is involved in your withdrawal and behaves like a “know-it-all” guy, then drop your doctor. Having come so far, you are likely to know much more about withdrawal than your doctor.

It is prudent to go down to a very low dose before you stop. Citalopram, for example, is recommended to be used at dosages of 20 or 40 mg daily, and it will surprise any doctor to know that even at a dose as low as 0.4 mg, 10% of the serotonin receptors are still being occupied,34 which means that you might still experience withdrawal symptoms when you go from that small dose to nothing. Psychiatrist Mark Horowitz admitted that if patients had come to him before he had experienced the withdrawal symptoms himself, he would probably not have believed them when they said they had real trouble coming off a depression pill.37

Don’t take it as a defeat if you fail; just try again some other time. Tell yourself that you deserve to have a good life and be determined to get it.

To read the footnotes for this chapter and others, click here.

If one takes the prescription book from a psychiatrist, one also takes the sting from the learning and metaphysics of their education and experience!

55-olaveivind

Report comment

With certain poly-pharmaceutical combos I think there is reason to believe that it may be easier to withdrawal from two drugs at once compared to one at a time. Psychiatry often will put someone on a second drug in order to address symptoms caused by the first. A sedating drug with a stimulant or SRI. One drug causes “upper” effects while the other causes “downer” effects. This can even take the form of taking a drug that increases dopamine with a drug that blocks dopamine. These drug combos counter act each other and maybe tapering both at once will reduce some withdrawal effects. Tapering a stimulant may make people tired. Tapering the sedative at the same time may reduce this tired feeling.

Another strategy that may help for those on drug combos is to switch which drug is tapered each time. For example someone taking a SRI and a stimulant would first reduce the SRI and then 2 weeks later reduce the stimulant. 2 weeks after, they reduce the SRI again and repeat. The person will still be in withdrawal for the same amount of time but their body will have more time to adjust to the dosage change of each individual drug before a new dosage change of that drug.

I have no scientific evidence to suggest if these ideas help; only anecdotal accounts which may be flukes that are wrong.

Report comment

That actually makes a lot of sense to me. I’ve seen kids get super aggressive on stimulants, then be put on Risperdal to “calm them down.” When someone prevailed upon them to stop double-drugging the kid, they always want to take them of Risperdal first, which of course then leads to the aggression they’d created with the stimulants, which leads to, “Oh, no, he’s having a relapse, we’d better abort!”

Report comment

Yes this is routine and I firmly stand by my view that it is intentional. And if not then the word “doctor” should be removed and also all privileges associated because

one then has proven that they have either no clue or are intentional.

Report comment

They don’t want to admit they caused harm so they cover it up with another drug. It’s either “sorry patient my drug is hurting you we need to reduce it” or “Your brain has 2x the illness here is an additional drug.” The. Some People end up taking 4+ drugs.

Report comment

I know, it’s disgusting. And they are often even WORSE on the 4 drugs than they were before they started the first! But the answer never seems to be, “Gosh, this doesn’t seem to be helping – maybe we should do something else!”

Report comment

Thank You again, Dr Gøtzsche

“…1. WARNING! Psychiatric drugs are addictive. Never stop them abruptly, because withdrawal reactions may consist of severe emotional and physical symptoms that can be dangerous and lead to suicide, violence, and homicide.6….”

Yes: “Rebounds” as a result of Psychiatric Drug Withdrawal – can be a lot more “Intense” than original “Problems”.

Report comment

“..Don’t take it as a defeat if you fail; just try again some other time. ..” Exactly!

Report comment

Thank you very much Peter for being there to help people and I especially like that you mentioned for people to have a friend or two, to walk alongside this journey of theirs. Alliance is itself comforting.

Report comment

Thank you, as alway, Peter, for your assistance in trying to help those who were conned by psychiatrists, psychologists, and the other DSM “bible” worshippers.

Just an FYI, neither this link:

https://www.madinamerica.com/2021/06/mental-health-survival-kit-chapter-4-part-5/deadlymedicines.dk

nor this link:

https://www.madinamerica.com/2021/06/mental-health-survival-kit-chapter-4-part-5/taperingstrip.org

works, at least not on my computer.

Report comment

Thank you for this article. I have been on medication since I was 18 and I’m now 47.

About 3 years ago with the assistance of a provider I tapered off of my antidepressant and anti-anxiety medication.( not simultaneously) I had minimum side effects thank goodness.

I’m still medicated by a mood stabilizer and antipsychotic. I have hopes to come off one of those soon as I have recently read that they have moderate interactions with each other. It’s upsetting to me that this was either overlooked or undisclosed to me.

With my continuing research and support that I hope to get maybe I won’t be on medication the rest of my life like I was told so very long ago.

Report comment

This is some of the best withdrawal information around. I encourage everyone to donate to the new Institute for Scientific Freedom that he is starting.

Report comment

Thanks Stuart.

I hope that some psychiatrists donate, they can afford it and it would be a worthy cause.

Report comment