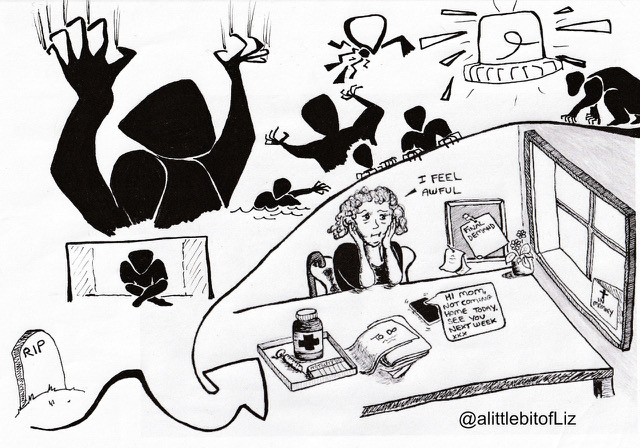

Imagine if, after leaving your house to run some errands, you were mugged. It would be pretty normal for you to feel anxious every time you need to leave the house after that! But after a while, you decide that you shouldn’t feel that anxious about it—muggings are very rare and it was just incredibly bad luck. Maybe you see a TV ad that says “If you feel anxious, you should talk to your doctor.” So you go to your GP for help, and the doctor diagnoses you with ‘Lack of Alcohol Disorder’ (LAD). Sounds far-fetched, but bear with us!

Your GP knows that LAD exists, because research has shown that people who drink alcohol tend to feel less anxious and more confident. When anxious people are given moderate amounts of alcohol, lab studies show they feel calmer. Therefore, lack of alcohol must be the problem: it is why you are feeling anxious. LAD is more commonly present in women, ethnic minorities, and people who have survived trauma. It is associated with the DRD2 dopamine pathway in the brain—after all, brain scans have shown that alcohol affects this pathway.

Initially, to treat your LAD, you are prescribed a shot of vodka every time you need to leave the house. This seems to work. After two months however, your tolerance has increased, and the alcohol doesn’t work as well. You are prescribed more and more alcohol by the GP to treat the increasing severity of your LAD (rather than increased drug tolerance). You struggle to concentrate, to go to work, and you gain a lot of weight—however, at least you can leave the house.

Eventually, however, you don’t like the medication side effects (nausea, dizziness, impulsivity, you can’t drive while taking it, and of course the headaches and lethargy in the morning before your daily dose) and you ask your GP to come off the alcohol. They do this cold turkey: You stop taking the prescribed alcohol but feel intensely sweaty, nauseous, shaky and incredibly anxious leaving the house again. Instead of recognising this as alcohol withdrawal, the GP explains that you must have chronic LAD, and unfortunately you will have to drink alcohol every day for the rest of your life. It may shorten your lifespan, but it is worth it to treat your LAD. You are offered a support worker who can help you try to do your shopping, and a community nurse who will help you monitor your symptoms and side effects.

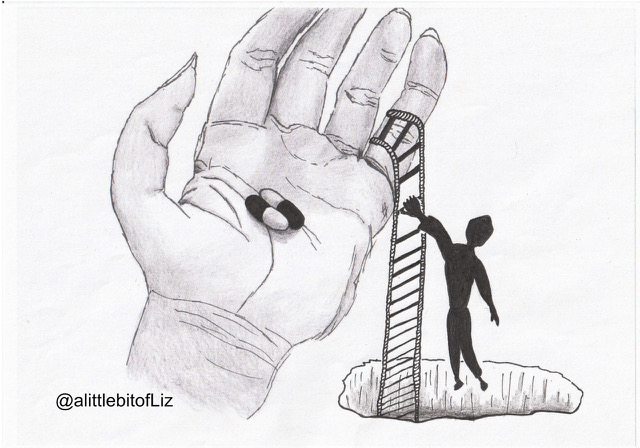

Another way of looking at this situation is that alcohol can lower our inhibitions, and even make us feel relaxed and safe, which might make leaving the house easier. But “lack of alcohol” was never the actual problem. Obviously, this is an exaggerated example, but it is an almost exact parallel to how we view drugs like antidepressants and “disorders” like depression.

The whole (now debunked) “chemical imbalance” theory of depression was developed because someone noticed that the drugs now called “antidepressants” worked on the serotonin system, impairing the reuptake of serotonin so that more of it remained in the synaptic cleft. So, the theory went, people who need antidepressants must have low serotonin (just as in our example, you are theorized to have alcohol levels that are too low). But, unfortunately for this theory, research never demonstrated such a serotonin deficiency, and in fact experiments showed that just impacting the serotonin system did not cause or relieve depression.

Likewise, antidepressants may cause a chronic, long-term depression (instead of what was once a time-limited experience). And they have significant withdrawal effects, which can last for months or years and look a lot like “depression.” Researchers have found that these effects are often mistaken for a return of the original depression, even though they are often worse or different from the symptoms which first brought a person to the psychiatrist.

In our example, the doctor mistakes alcohol withdrawal for a return of the “Lack of alcohol disorder.” It seems far-fetched that a doctor could make that mistake. But doctors make the exact same mistake all the time when it comes to withdrawal from psychiatric drugs.

Worse still, in our example, with all the focus on the “treatment” of LAD, the original problem, the reason you felt anxious when leaving the house, was never addressed. That’s the same too—your GP or psychiatrist will give you a prescription for a drug, but they won’t address why you felt anxious or depressed. (A whole separate field is devoted to exploring why you might feel that way and how to change it; it’s called “psychology.”)

You may be someone who has found antidepressants incredibly helpful. We are certainly not trying to invalidate your experience. Just because these drugs make some people feel better at times, doesn’t mean we have to accept that the drugs will help everyone, or that the people who are helped by such drugs are ‘mentally ill’. After all, alcohol works—relieving anxiety, making you more social, lowering your inhibitions so you can leave the house! But that obviously doesn’t mean it should be considered the medical solution for anxiety.

Considering this hypothetical example, it is not hard to see how one could find themselves in a negative relationship with substances that provide temporary relief, such as alcohol, or in the medical world, benzodiazepines or opioids.

One critique of the medical model is that society has a negative perception of ‘self-medication’ but the same substances are readily prescribed by healthcare professionals as treatments. For example, college students using Adderall or Ritalin to focus on studying before a big test or to write a paper is frowned upon, but if a doctor prescribes the same drugs (amphetamines) to children to improve their schoolwork, it is considered beneficial.

Another example: Drugs that were once considered “recreational” drugs, their use criminalized (ketamine, psilocybin, even marijuana) are now being prescribed as “treatments” for a variety of psychiatric diagnoses, including anxiety, depression, and PTSD.

At this point, you should be noticing that psychiatry’s biological treatments (drugs) have the same basis in science and the same underlying assumptions as self-medicating with alcohol. And they may work in some ways, just as alcohol “works.” (After all, people wouldn’t use it so much if it didn’t feel good!) But they don’t resolve the underlying issues that cause people to feel distressed, they come with a great many negative effects, and they can be very hard to discontinue.

However, if there was a shift in the paradigm (if we could adopt the paradigm that Emotions aRe Not Illnesses) then this would change the way we view ‘mental illness’ and as a result it would change our response. We might start looking for the cause of distress instead of just tranquilizing the symptoms.

The paradigm shift

American philosopher Thomas Kuhn first introduced the notion of ‘paradigm shift’. Science doesn’t gradually converge towards a universal truth. Instead, it goes through phases. A paradigm shift happens when a fundamentally new way of thinking and conceptualising the world better explains the evidence available, something incompatible with the original beliefs. Generally, the paradigm shift happens upon the increasing weight of new evidence that simply cannot be assimilated into the current way of thinking.

Psychiatrist Thomas Szasz suggested that diagnostic categories for mental illness diagnosis are only a metaphor, like drawing constellations in the sky: the stars are there, and they are very real, however the way that we draw our constellations is essentially a social construction. The ‘symptoms’ of the things we sometimes call ‘mental illness’ are real. The very concrete, and at times life-threatening, impact of distress on people’s emotions, thoughts, behaviour and body, is real. However, Szasz argued that the ‘illness’ paradigm of understanding this distress can be actively harmful.

The need for a paradigm shift can be contested, given that much mental health practice and research is already ‘interdisciplinary’. However, it is important to understand that we have not yet reached the point of paradigm shift. Many suggestions for ‘alternative paradigms’ to mental health in reality do not meet the criteria for a paradigm shift. Instead, they remain as adjustments to the existing medical paradigm.

Many in the mental health field consider themselves to be “integrative”; psychiatrists often espouse a bio-psycho-social paradigm. Nonetheless, they invariably situate mental ‘illness’ within biomedicine and explain it as a “complex” biological mechanism (as yet undiscovered) that “we believe” involves genetics, neurotransmitters, hormones, and even immune functioning . Social influences like poverty, homelessness, discrimination, racism, and sexism are considered, at most, “triggers” for a biological illness. Non-medical options like psychotherapy are considered to be ways of managing this biological problem, rather than ways of explaining and addressing the cause of legitimate distress.

A real paradigm shift would be more than continuing to give diagnosis and drugs whilst ‘integrating’ psychological, social and cultural ‘factors’ or ‘acknowledging’ socio-political and historical context. We contend that any diagnosis-inspired models with the words ‘include’, ‘integrate’, and ‘acknowledge’ in relation to cultures, social life, personal history, community, and relationships, are not paradigm shifts.

The very concept and language of individual ‘mental health’ is part of the medical paradigm. Approaches which accommodate community, personal narratives, stories, and meaning, but which accept diagnostic categories or an illness/biological understanding of distress, do in fact sit nicely within the existing medical paradigm. We need to change something deeper, more wider-reaching, more fundamental about the way we look at human distress. We do need a new paradigm.

The future

The medical paradigm suggests an ‘us’ (well) and ‘them’ (ill) dichotomy. Mental health research, therefore, focuses on the views of ‘professionals’, those with advanced degrees in the subject. “Service users,” if considered at all, are thought to lack credibility and their views are usually discounted. Even professionals with lived experience are often dismissed with the argument that their experience with the very subject under discussion compromises their “objectivity” (or simply makes them “crazy”).

What is needed are genuinely co-created narratives where, if professional views are even useful, the lived (and life) experience of the person with distress is the strongest and most credible ‘evidence’ for what might help them feel better. Where co-created narratives include professional support, they should emphasise social, historical, political and community factors. This isn’t to eschew the training of professionals (for example, listening skills and evidence-based techniques to manage distress). However, these skills should be situated within a helpful, and more human, paradigm.

Do we have a singular perfect alternative? Of course not. There is a real danger, in this commoditised point in history, that critiquing the paradigm imposes a pressure on ‘powerful people’ to come up with a succinct and sellable alternative.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t work towards change—and work has already been done. The Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF), for example, takes a human-rights focussed approach to distress, based on the meaning that people make of adversities they have faced and their response to these adversities. It also considers their strengths. The PTMF acknowledges that diagnosis is imposed on those seeking support, further reinforcing their feelings of shame, of being different and somehow “disordered”. This denies people the opportunity to create their own narrative, with which they could make sense of what has happened to them.

One of the aims of the PTMF is to be used to construct service design and policy based on the ideas of those with lived experience rather than professional “theorizing.” The PTMF acknowledges it is not the perfect solution, but provides the foundation on which to build. Perfect or not, this is what a paradigm shift might look like.

The paradigm through which society views something dictates the responses it has available. As the saying goes, “if all you have is a hammer, everything starts to look like a nail.” If all you have is a medical paradigm, everything will start to look like a symptom of an illness, and the only solution will be biologically based.

The PTMF proposes a paradigm shift from “what is wrong with you?” to “what has happened to you?” This immediately shifts the selected response. We propose that emotions are not illnesses, and therefore, the solutions to human distress are human. It’s in our communities, it’s in our relationships, and it’s in the way we make sense of things together.

Editor’s Note: The ERNI Declaration is available here.

Thank you both for this beautifully written and powerful post. Analogies like “low alcohol disorder” are a great way to highlight the absurdity of the biomedical paradigm. I will encourage my students to read this. That said, in order to be accredited, our program is required to train students in the “emotions are illnesses” paradigm and demonstrate they have “competency” in it.

I fully agree with your point that there is no such thing as “integrating” the biomedical model with a more holistic approach because such integrations still rely on the core assumption of medical illness. That’s why I think the “biopsychosocial” model many hold up as the ideal doesn’t really change anything and is far from a paradigm shift. An actual paradigm shift involves fully rejecting the notion that problems of thinking, feeling, and behaving are medical illnesses. The issue then, for our profession, is that we have to throw the entire educational apparatus out the window and start over from the beginning. In my view, this could be a good thing. However, no program that did so would have any chance of being accredited. This is a difficult problem to solve.

Report comment

Brilliant Article

Attraction rather than Promotion:

What costs nothing, is reliably confidential, adaptable, available, voluntary, and proven to work is 12 Step fellowship.

Adaptable and Proven to Work:-

https://youtu.be/YT2ecA6bJ1c

Report comment

There is a non-drug mechanism that worsens the women’s mental well being in the story. She has whichever compilation of negative feelings coursing through her because of being mugged. When she goes to the “brain experts” and doctors they tell her, “It is because your brain is ill like cancer and therefore you need drugs to be “mentally healthy””. Essentially her being mugged is blamed on her, specifically her “ill brain”. If she had any thoughts that it was her fault (society does often blame women and people for being assaulted or abused) she now has “expert” consultation telling her yes it is your fault. Her self esteem is reduced. She has been informed she is hopeless and powerless and when the active placebo effect dissipates that feeling will hit harder.

One effect of claiming distress is an “illness” is that people will be less likely to talk and share what is causing them distress. Telling the psychiatrist you are sad and can’t sleep will illicit the same response as telling them the sex abuse is making you sad and unable to sleep. It is a lot less distressful to remove the sex abuse part especially when the psychiatrists claims your distress from it is “your ill brain”. This creates a feedback loop where people don’t share and that makes the psychiatrists believe all those emotions and behaviors are caused by an illness. What is interesting is that in psychiatric scales measuring mental health someone mentioning poor physical health, complaining, or refusing to blame their brain are signs of worse “illness”. If anyone is a cynic it appears psychiatry considers a major benefit to be getting people harmed by society to shut up about it.

Report comment

The analogy with alcohol is very interesting. The sad part is that psychiatric drugs do lower your inhibitions as does alcohol or why would they not prescribe these drugs allegedly for anxiety, etc. The other point to be made in this analogy is that the truth is they have made up alleged mental illnesses to fit their prescribing and dispensing of these dangerous psychiatric drugs and therapies. However, a person is probably more likely to get stopped for drunk driving than drugged driving; but the latter does happen. Still, the main point here is that psychiatric diagnosis and their associated treatments are not only very dangerous, but a joke on all who have bought into their deception and lies. Thank you.

Report comment

County Kerry: Criminal investigation launched after three found dead:-

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-58483201

Nobody but Nobody mentions the Elephant in the Living Room (and it’s not Alcohol).

Report comment

I would think that a paradigm shift should also include how psychology views distress as the dominant view taught at universities is still that something “in” us causes our distress such as faulty thinking, cognitive distortions, activated schemas, etc. David Smail’s quote probably sums this idiocy up best: “It is about as sensible to seek the reasons for distress inside the ‘self’ as it would be to see feeling cold as a matter of personal responsibility.”

Report comment

I think whether or not distress comes from inside a person or outside a person should be a moot point. The important thing might be is there distress? Most problems that could be termed distress actually have practical solutions. Psychiatry just wants to drug and therapize the person and say it is all because the brain is broken. The brain is not broken. If the brain were broken, the person would be dead. What they continue to deny is that each brain, like each person is unique and there are unique solutions to the problems each person faces within the truth of absolute right and wrong. It is just easier to deal with the lie that truth is relative and that we are all alike—a virtual collective; but we are not robots. We are human. And psychiatry, etc. needs to treat us as such. Thank you.

Report comment

The intro using alcohol was very witty!

No kidding we need a “paradigm shift!”

But I am unsatisfied with what the authors propose, because, from my point of view, their own paradigm about how life works has not yet shifted enough!

Their “new” paradigm still implies that people only live once, are basically super-evolved animals, and just need to learn better how to get along. From what I have learned, this is basically incorrect. So the new paradigm, though obviously more humane, would not make that many people feel better. Maybe 25%?

My own paradigm starts with these “facts of life:” A person is a spiritual being who has lived many multiples of lifetimes in many different places. A person brings all that experience into this life, although usually as forgotten experience. The body is a sophisticated animal which could in theory survive without a human personality associated with it, but rarely does. Thus, the body can be seen to have a “mind of its own” to a certain degree. It also brings experiences from former lifetimes forward into this one, again in a forgotten state. The difficulties a person may encounter in this lifetime are thus an amalgamation of this life’s experiences and the (usually) forgotten experiences of two beings, one an animal-type being and one a human-type being. This can make healing a difficult process for some beings, and likewise requires a well-trained healer or facilitator, should that be desired. The key to unraveling each individual’s personal riddle lies with the person themselves, and how much they are willing to learn about life and about the techniques that have been developed so far to help people heal. This is usually done by learning some of those techniques and then trying them out on someone else.

Healing from psychic trauma of any sort is not a voyage for the faint of heart. But done by steps that are relatively easy to confront, it can eventually be achieved. Good luck to those who try! For those who don’t feel up to this, just get enough rest, good food and a calm environment. Likely, you will get better if you can just get those things. This is the greatest challenge on Earth today! Those basics of rest, food, environment are unobtainable for so many!

Report comment

i scanned the article briefly. A twelve step friend pointed out, by chance….So I’ll need to go back and reread more thoroughly. But I found the author’s biography equally compelling: “NHS learning disability services, she now works as a university researcher and tutor on mental health, and is completing a Masters in human rights. Chey believes strongly in the power of stories.”

I am an artist. A poet and essayist. I have been in alcohol and chemical recovery for 35 yrs. I don’t particularly subscribe to the twelve step programs or the medical model. i suppose i like James Hillman or R D Lang or Michael Cornwall of this publication.

i like the James dean’s of the mental health profession. They are as much authors, poets, social scientists, archeologists than clinicians…..Since i was also very dyslexic as a kid formal learning was ” out”. And i mean ” out” …..What i was left with was the imagination, a few hockey pucks and sticks. The frozen pond or the driveway, tennis ball, neighborhood kids all became purview, my canvass. The same with writing. I wrote on my bedroom wall. I appreciate all the outside the box thinking, i do. I have a Sister that is very stubborn and fragile. And i am sure I’ll never figure Her out or fix Her. But opening the imagination through stories and art with Her somehow helps. this is what comes to me after 50 years.

Report comment

Thanks for an interesting article, but I think the link to alcohol is even stronger than you suggest. I was on anti-depressants for 29 years, and it is obvious to me now (over 4 years off) that my brain was being impaired the entire time I was on them. So by impairing and altering normal brain function both alcohol and psychiatric drugs CAN reduce symptoms and make people feel better. However, the brain impairment can actually be a block that prevents people for making changes in their lives and truly addressing their problems. So I could go to group therapy and get all kinds of insights into my life and changes I could make to improve myself, but I was unable to make real and sustained change due to the brain impairment. Now, off the drugs, I just do it and my chronic depression is gone! (But I have substantial brain damage.)

Report comment

I agree. I am actually very allergic to alcohol and developed this allergy even before I was put on all these psychiatric drugs. In fact, none of my intake interviewers at any clinic I went to ever questioned about any alchohol usage prior or present. This was true even for a stint in both a day hospital and as an inpatient at the local “mental hospital.” I am surprised that I lasted so many years on this drugs, but they kept adding and subtracting, and changing the drugs. I can not remember all the drugs I did take for all those years. Now, I can not even take a pill. I can not even get near alcohol even if cooked in some recipe. In fact, now I have developed an allergy to about every drug, especially those that are taken internally. I also have an allergy to so many foods and other substances that I must adjust my life accordingly. I am terrible dinner and/or house guest for sure, I am lucky to be alive and am forever grateful to God for saving my life. Thank you.

Report comment

I have two movement disorders clinically diagnosed after close to 9 years of being told my problems are all psychogenic/functional neurological in origin. I was very fortunate through life circumstances to be referred to a very experienced neurologist, professor emeritus in neurology at a major university in Ontario, Canada who after a very detailed clinical examination and analysis of all the tests and diagnostics I have had done over the years, indicated this is not at all functional or psychogenic but rather Paroxysmal Kinesigenic Dyskinesia combined with parkinsonism, started me on levodopa and so great with this medication, I’m not falling down nearly as much as fefore and many, not all, but many of my parkinsonian symptoms, especially dystonia type symptoms, are so much reduced. May start me on anti-epileptics if required in the future if my PKD gets worse but not a major issue at this point. That being said, I do like a bit of alcohol daily and it helps, along with me exercising and walking and lifting weights for about 4 hours daily. A couple of drinks before dinner, works! See:

“Synaptic effects of ethanol on striatal circuitry: therapeutic implications for dystonia”

https://febs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/febs.16106

Report comment