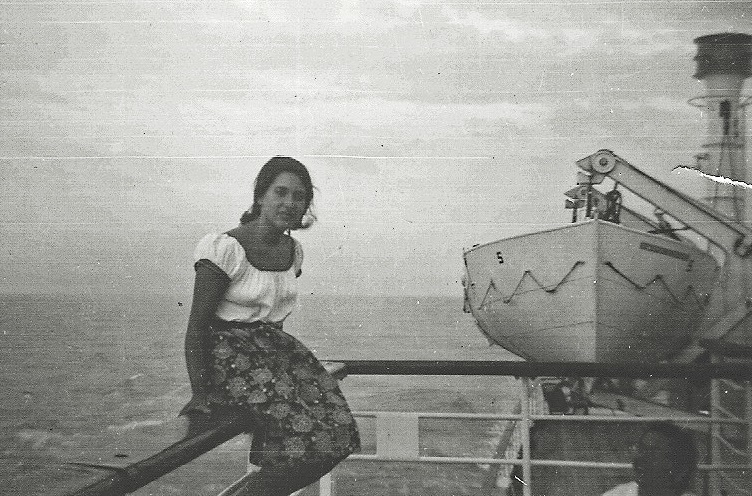

Older than me by three years, Rachel was my touchstone during our childhood. As our family moved from one city to another through the 1950’s I looked up to her. I saw how she immersed herself in books and piano practice—and I did the same. In high school she pointed me toward teachers and friends who would challenge “conformist” thinking. We had the same olive skin and brown hair—people said we looked alike. But her blue eyes were quicker to flash in anger, especially at parental expectations. She pushed hard against their limits so I hardly ever needed to.

After high school, Rachel decided to go to Israel. She returned a year later, bronzed and glowing, lean and wiry from working citrus groves and potato fields on a kibbutz. She knew she didn’t want full-time college; she wanted to be a poet and travel. So she crisscrossed the country finding friends to stay with. She signed up for occasional college classes, worked in an office when she needed money. I thought Rachel was boldly exploring new possibilities and I dismissed our parents’ worries about her lack of direction. I didn’t know until years later—when a friend of hers told me—how unusual her behavior had become: how she sat naked in a pitch-black basement apartment playing the oboe, her translations of Rimbaud taped to the walls. What I did witness, whenever she came home, was how she paced the living room floor all night, lighting one cigarette after another. She didn’t talk much except for angry exchanges with our parents.

I understood something was seriously amiss when Rachel confided to me that two men had followed her from New York to San Francisco. She saw them in the park near her office, she said. I could see she was in great distress and I sensed she was delusional. Only later would I remember how our parents had been surveilled and harassed by the FBI during our childhood because of their political activities. Then I realized that Rachel’s fears, irrational as they appeared now, had roots in our family history.

In July of 1965, at the age of twenty-two, my parents had her declared incompetent and Rachel was committed to St. Louis State Hospital. I was working as a counselor at a summer camp and got the news long distance: Rachel was ill, they said, and needed treatment in a psychiatric hospital. I was shocked and shaken. My younger sister, who was attending the same camp where I was working, needed comfort but I was too confused to provide it. I couldn’t explain what was happening because I didn’t understand anything about it. I don’t think I had yet been told the diagnosis: schizophrenia. My mother always hated the word and refused to use it. She believed Rachel had suffered brain damage from a high fever she had in Israel.

It was hard at first for me to fathom my parents’ decision to institutionalize her even though I knew about two crises that had led to emergency room visits. When she was in New York City ready to board a plane to Montreal the friend she was traveling with called my parents and told them Rachel was hallucinating. She asked them to come get her. When she was in San Francisco, where she was working in a law office, her boss called my parents with the same urgent plea.

I knew Rachel needed help but I didn’t understand why she had to be locked up. “State Hospital is involved in a new program with the university,” my mother assured me. “They have drugs now that will make it possible for her to talk with somebody, so she can get better.” My mother never said, and I don’t think she herself believed at first, that commitment was a sentence for life. But that’s how it turned out. Not entirely, but just about.

My parents thought it was important not to let Rachel’s condition change the course of her siblings’ lives and they kept talk about her to a minimum. My brother, younger sister and I learned about Rachel’s incarceration separately, and in bits and pieces. We didn’t even get to talk to Rachel at the time. We didn’t meet as a family to discuss what was happening or what this might mean for the future—Rachel’s and ours. If we had, we might have better understood and shared what we most valued in our lives. We might have found more ways to be more involved and helpful, made better life decisions and found better ways to cope with our own pain. Their approach was understandable but ultimately misguided, I believe. We were affected anyway—with fear and sorrow, with guilt and anger.

By 1965, psychiatric hospitals had already started the process of closing down and Rachel went through the revolving door many times—from hospital to home to back to the hospital. Over the next few years Rachel fought so much with our parents that they felt she couldn’t live at home. She traveled to Chicago and Tulsa and New Orleans. The police would take her in for vagrancy or shoplifting. Our father would bring her back to the hospital for re-admission and our mother would plead for the hospital to stop discharging her because it was the only place, she believed, where Rachel was safe. The officials in charge of community placement, however, sent her to boarding houses anyway. They never worked out. She was assaulted and raped and ended up on the streets.

When I visited Rachel in State Hospital that first summer, I was horrified by the locked doors and the desolate lounge where I sat with her. She didn’t want to talk to me, and I could see how angry she was. I knew she was on psychotropic medications but I didn’t know the extent of the damage they could do. Not just the facial tics, thick tongue and a protruding stomach, but also diabetes, decline in intelligence, teeth lost to dry mouth and, most ominously, stubborn recurrences of impulsive flight. Over the years, as Rachel kept ending up back at the hospital, I came to believe she had a terribly severe and incurable form of schizophrenia. It didn’t occur to me then that her psychiatric treatment was making her worse instead of better. Or that my mother was right about the uselessness of her diagnosis.

I had always loved and admired Rachel. But when her life became so chaotic and her needs so overwhelming, I felt helpless. My parents assured me they were looking after her and I needed to trust them because that left me free to live my own life. I wanted college, marriage, a family and a career. I absorbed my parents’ belief that none of this would be possible if I became involved with Rachel’s care.

My brother, on the other hand, never reconciled himself to Rachel’s involuntary commitment. He distanced himself from our parents’ actions and in 1979, after a visit to Rachel in St. Louis State, became alarmed enough to intervene. By then, a federal lawsuit our father filed (Goodman v Parwatiker) made its way to an appeals court. Rachel had a constitutional “right to treatment,” my father argued, and could not be discharged for reasons of “efficient management” as the hospital claimed. I supported my parents in their effort to reform the system and held out some hope that it would help Rachel. My brother believed that settlement of the lawsuit would keep Rachel incarcerated indefinitely. So in 1979, almost fifteen years after her first commitment, he decided to free her. He appealed to me and our younger sister for financial and moral support in bringing her to live with him in Seattle, where he would oversee her care.

By then I was living in Connecticut, where I was focused on my own family and career; my younger sister was in New York City. We dissected and critiqued my brother’s proposal and finally agreed to meet with our parents and tell them we supported it. For the first time since Rachel’s first commitment we met as a family—all six of us. Faced with four children now unified in a plan for freedom, our parents reluctantly agreed to release Rachel to my brother’s care.

The rescue failed. After a particularly bad fight with our brother, Rachel signed herself in to a local hospital. She was then transferred to a state psychiatric facility, but she took off and ended up in Portland where an arson arrest landed her in the state hospital there. My brother now believed she should be left on her own to figure out her life. My younger sister suggested she be placed on the East Coast, since we both lived there and could more easily visit her.

My parents felt the Oregon psychiatric system was probably better than Missouri’s and wanted to leave her there. I agreed with them. I thought about the physical environment in the northwest and how it would be healthier for her than the urban streets of St. Louis or New York City, where she would inevitably be drawn. I hoped she would soon be free to do her writing and her wandering in the west. Even if I couldn’t visit her, I could write to her or talk on the phone across three thousand miles, I rationalized. The family distancing viewpoint prevailed and Rachel stayed in Oregon. I lived my own life, just as my parents had always wanted, and I had too. But my bouts of depression, which had begun when Rachel was first hospitalized, continued. It took me a long time to understand the relationship between what happened to Rachel and my own up and down emotions.

For the next fifteen years Rachel was sent back and forth among three psychiatric facilities in Oregon. Whenever she was deemed stable on medication she was discharged to a group home or a boarding house, but she would never stay for long. She couldn’t follow rules about sex and drinking and would get herself kicked out. Rachel seemed to prefer to be homeless and camp out in the woods. She would go to Salvation Army for food and shelter. When the weather got bad enough, she even got herself re-admitted.

When she was in a hospital in eastern Oregon I traveled out to visit her and saw her condition firsthand. Her speech was so slurred by then it was hard to understand her. I took her to lunch at a diner and when she stood up I saw she had wet her pants. A nurse at the hospital explained that she refused to wear paper underwear. A doctor called me into his office to tell me she was climbing into women’s beds at night and molesting them. Did I have any ideas why she did that, he wanted to know. I had the feeling he wanted me to do something, but I had no idea what to do or say. Again, I felt helpless and hopeless.

Finally, and against all odds, Rachel found a way out of the back wards of the hospital system. She applied, in the early 1990s, for a work program and on a trial visit to an agency in Eugene she met Steve, a case worker who was determined to help her. When she told him she liked to write, he put a typewriter in front of her. He was astounded by the poem she wrote:

Water

An ellipse adjoins the river

Water that shushes by;

Narrow thin stream of water

silt carried with the gentle

murmurs of life exhumed.

Flashes of lightning and bright rapids

of slow treacherous instincts.

White tails of fish rapidly charging

down stream, down currents with

foam on crests of waves and love

in my treacherous heart for these

mute gods of Neptune haunting

the great abyss of longing.

For as each sailor ties a knot

I go down deep till bright waters

roll over and over

the sinking hulk of my body

covered by each wave one by one.

Still the water’s placid.

Each ripple of river-water

flowing along

very unaware of the piece of humanity

it has eaten, floss on the waves.

—Rachel Goodman

“Nothing in her file even mentioned her love of poetry,” Steve told me. He was determined to keep her out of the hospital, but Rachel’s condition looked too severe for the agency work program. They were ready to send her back but after Steve read her poem “Water” to a stunned staff, she was accepted. He and his colleagues found ways around the difficulties Rachel presented. They obtained housing for her and provided supportive services. Rachel joined, for a while, the crew that cleaned offices at night. When she could no longer work they still supported her.

Her behavior made it as hard for her to keep an apartment as it was to live in a group home. After a few years, the agency found her a tiny house of her own near the Willimantic River. Staff came to her there to bring her medication, which she had the freedom to take or refuse. She enjoyed her cats, her cigarettes, and her long walks in the woods. She even found her way to a local synagogue, where a group of women urged her to return after she had showered. Having responded to their encouragement, they honored her with an aliyah: she stood in front of the congregation to lead them in the Hebrew prayers she remembered from her childhood.

Rachel lived in her home for eight years. When she was fifty-nine, she died suddenly one night of untreated bronchitis. I had visited her less than two months before and had been alarmed by her smoker’s cough but I knew she would never give up cigarettes. That night, when she struggled to breathe, her boyfriend ran to the main road for help. By the time help arrived it was too late. Her social worker told me she had called a doctor, but the appointment wasn’t scheduled until the following week.

When I reflect on Rachel’s life I am consoled by the knowledge that she was free in her final years—in a house of her own and with a community that cared for her. But I can never forget how many years were taken from her, or my inability to help her. It takes a long time to recover from a psychotic episode, I understand now, and I wish someone had found a way, especially during those early years of her troubles, to give Rachel more space and time to find her own path to health. Instead, she was labeled and medicated, time and again, in ways that diminished her autonomy and her capabilities.

For decades, Rachel wrote poetry to make sense of her experiences. In a stroke of luck she met up with someone who viewed her as an artist, not a mental patient. He engaged her, listened to her, and became her advocate during her transition to community living. His formal education was not in mental health, but he knew how to help people whom others had given up on. Because of him Rachel gained both freedom and care—which is what her parents and siblings had always wanted for her but were unable to provide.

Your sister’s poem shows a mind that could still think and comment obliquely. Others must have asked: are you sure she was delusional? Your piece mentions the FBI investigating your parents about politics. And that your sister came back from a trip to Israel and said two men were following her. Has it be done, is it possible, to look for evidence that she was not delusional? Can you do, have you done a records search and see if you can get your hands on any files?

I was falsely accused of being delusional almost ten years ago. Now 58, the last ten years have destroyed me and I am sure lessened my life expectancy. My maternal grandmother lived to 102; I doubt I will, but would not want to endure that much more torture because I would be locked up again at this rate of destruction. Certainly the alleviation of growing long term torture is the best thing for a person. You seem to indicate your sister could live best on her own terms, with her own agency. Of course!

What I endure is torture that grows without justice and acknowledgement that I have been greatly wronged. 300 teachers of Oakland Community College and the in-house faculty union in Oakland County, Michigan, own/owe me greatly for pretending I never existed on campus, for seven years, a tenured teacher, then suddenly disappeared–because I talked about teacher-first ways and a reading crisis. Many own/owe me greatly: Oakland Community College, Livonia Michigan Police, St. Mary Merciless human trafficking mental ward, and the state of Michigan.

Mental torture for sure causes problems. I have been made ill by unnecessary mental health care and especially by all these years not being heard and even the object of retaliation. I am being too slowly ripped apart and tortured to death, but I have no one else who will write my story.

And like your sister, I can’t defend myself. Trying to do so has not helped.

https://ginafournierauthor.com/

Report comment

Gina, yes, others have asked the same question about the FBI situation. Per your suggestion, I just submitted an FBI FOI request. It may take a while, but I hope to get a definitive answer at some point. Thank you for the suggestion and your heartfelt comments.

Report comment

I will say for it me: Gina, you are believed.

Report comment

May I say the poem included is sublime.

Poems outlive our silence.

Report comment

What a loving tribute.

Some people experience hard lives and I know

that psychiatry makes them a whole lot harder.

I understand that many people are of the mind

that we “need psychiatry” because there is nothing else.

And that is about the only reason psych exists.

That tells us something.

I can tell that you all loved her and so glad she was able to get away from psychiatry.

A few people is all it took to give her freedom.

Report comment

Although Rachel was very loved you don’t mention much about her childhood and maybe her experiences that must have affected her later in life.

She was a true artist and my brother left poems before he died and took his life.

I have a poetry blog and draw cartoons.

My mother attempted in vain to keep me away from doctors and out of hospital.

Sanctuary is needed. Depersonalisation is not. Medicalising is not needed.

People who suffer for their sanity can find peace and solitude.

I have experienced this myself now and my son also.

Thank you!

Report comment

Thank you for this beautiful writing about your sister; I am moved to tears.

Report comment

Thank you for writing about, and sharing, your beautiful sister’s story, Deborah. I’m so sorry she was, for so long, controlled and harmed by the psychiatric industry, but glad she eventually escaped. Us artists seem to be the primary targets of the psychologists and psychiatrists.

Report comment