In a new study in Nature, researchers found that the most common brain imaging studies in psychiatry—those that use a small sample to compare brain structure or function with psychological measures—are likely to be false.

These studies, according to the researchers, find a false positive result—a result that is due to chance statistical correlation rather than an actual effect. These highly positive results—even if false—are the most likely to be published.

Then, when future researchers attempt to replicate the findings by conducting another study on the same correlation, they find a negative result. This has been termed the “replication crisis” in psychological research.

The researchers refer to these types of studies as BWAS or brain-wide association studies.

“BWAS associations were smaller than previously thought, resulting in statistically underpowered studies, inflated effect sizes, and replication failures at typical sample sizes,” the researchers write.

The research was led by neuroscientist Scott Marek at Washington University in St. Louis. The study was also reported on by The New York Times.

Marek and his colleagues studied brain scan correlations from around 50,000 participants using three enormous datasets. They found that the correlations between brain volume and function and psychological states were much smaller than individual brain imaging studies have suggested.

Marek and his colleagues studied brain scan correlations from around 50,000 participants using three enormous datasets. They found that the correlations between brain volume and function and psychological states were much smaller than individual brain imaging studies have suggested.

In statistics, correlations like these are measured on a scale of 0 to 1. A correlation of 0 means there is no connection between the data, while a correlation of 1 is a perfect match. (However, even random data is likely to correlate slightly by chance.)

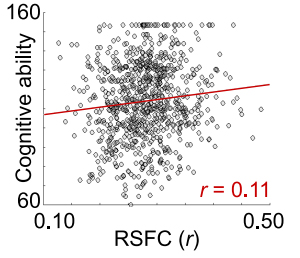

In their study, the average correlation between brain measures and psychological measures was 0.01—about as close to 0 as a test like this will ever reach. The largest correlation that they were able to replicate reached 0.16—still a far cry from a clinically relevant correlation.

A good correlation—one approaching 1—looks like this.

And here’s an example of one of the correlations from the study. This is the correlation between cognitive ability and resting-state functional connectivity:

The fact that these correlations are so small indicates that almost everyone overlaps on these measures. For example, almost every person diagnosed with “depression” will have the same brain connectivity as someone without the diagnosis. Likewise, almost every person diagnosed with “ADHD” will have the same brain volume as someone without ADHD.

Yet, in the smaller studies that are far more common in psychological research, correlations are almost always greater than 0.2 and sometimes much larger.

So why the discrepancy? According to Marek and his colleagues, these smaller studies are inflating these correlations due to chance variability—and then only the most inflated actually end up being published.

The most common sample size for these studies is 25 people. At that size, if you conducted two different studies, they could easily each reach the opposite conclusion about the correlation between brain findings and mental health.

“High sampling variability in smaller samples frequently generates strong associations by chance,” the researchers write.

The established method for dealing with this is to increase the threshold for statistical significance (called a multiple-comparison correction). However, according to the researchers, this can actually backfire in these small MRI studies because it inadvertently ensures that only the largest—and thus, least likely to be true—brain differences end up passing the significance test and then being published.

These chance findings and inflated results are ubiquitous in these studies. And even larger samples did not solve the problem. Only massive studies in the tens of thousands began to find more reliable (and tiny) correlations.

“Statistical errors were pervasive across BWAS sample sizes. Even for samples as large as 1,000, false-negative rates were very high (75–100%), and half of the statistically significant associations were inflated by at least 100%,” Marek and his colleagues wrote.

This is far from the first time researchers have noted that brain imaging is unreliable. MRI data is massively complex and notoriously “noisy”—full of random fluctuations that the researchers have to account for in order to find meaningful results. Computer algorithms are used to guess which data is “noise” and which data is important.

In a 2020 study in Nature, 70 teams of researchers analyzed the same brain imaging data. Each team picked a different method to analyze it, and they came to wildly different conclusions, disagreeing on each outcome measure.

A study from 2012 found thousands of ways of analyzing the same MRI results and multiple ways to try to “correct” those analyses. In the end, there were 34,560 possible final results and no way to choose which of these was “correct.”

In a 2020 commentary in JAMA Psychiatry, researchers argued that any conclusions based on MRI scans needed to be considered inconclusive and preliminary. Other researchers suggested that brain imaging was too unreliable to be a useful tool in psychological research.

****

Marek, S., Tervo-Clemmens, B., Calabro, F. J., Montez, D. F., Kay, B. P., Hatoum, A. S., . . . & Dosenbach, N. U. F. (2022). Reproducible brain-wide association studies require thousands of individuals. Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04492-9 (Link)

“brain imaging was too unreliable to be a useful tool in psychological research.” My psychiatrist told me this way back in 2003 or 2004.

Report comment

This has always seemed true to me, but everyone seems to think they are very “sciency.” I remember a study showing that including brain imaging pictures in an article, even if it had nothing to do with the content of the article, made people more likely to find it credible.

Humans are unfortunately too gullible in many cases.

Report comment

Well, at least my psychiatrist avoided lying to me … about one thing.

Report comment

Thank you for presenting this.

Report comment

It is not about what these photos show. It is about the attitude. Brain scan show particular state of the psyche. And only this. The rest is in the eye of the beholder.

Report comment

There’s another problem with all these BS studies. Correlations are not transitive in the way these studies pretend them to be.

Let’s assume there is some physical illness we can call depression, and it’s correlated positively with the symptons in DSM or ICD, and those symptoms are correlated positively with diagnosis of depression, and that diagnosis is positively correlated to some brain anomaly.

These studies assume that a positive correlation between the depression and brain anomaly would follow. That’s not true in general.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1198/000313001753272286

Report comment

I agree. It’s also true that correlation can be “significant” in terms of P values, yet there can be enormous overlap between those “having” and “not having” the anomaly in question. To be diagnostic, a particular “anomaly” has to occur in all or almost all of the test subjects, and in none or almost none of the control group. The fact that “ADHD” diagnosed kids have a 5 percent smaller brain volume (notwithstanding the issue of drug effects on brain size) means almost nothing, because 95 percent of the kids will have brain volumes that overlap with the “normals.” So the smaller brain size, whatever the reason, doesn’t indicate “ADHD,” because too many non-ADHD people have the same brain volumes as “ADHD” people. Of course, there is absolutely NO reason to expect that a random-ish list of behavior that adults tend to find annoying would somehow translate into a measurable “brain dysfunction.” So the whole effort is pretty much a waste of time.

Report comment

It’s an abuse of the double meaning of significant. A statistically significant difference does not have to be significant (in its colloquial meaning of meaningful).

Report comment

Precisely!

Report comment

What a surprise (not)

Report comment

Can someone tell me whether I translated this correctly (don’t know what to call such jargon as “scientology” is already taken so might call it “scientism”);

“The most common sample size for these studies is 25 people. At that size, if you conducted two different studies, they could easily each reach the opposite conclusion about the correlation between brain findings and mental health.

“High sampling variability in smaller samples frequently generates strong associations by chance,” the researchers write.

The established method for dealing with this is to increase the threshold for statistical significance (called a multiple-comparison correction). However, according to the researchers, this can actually backfire in these small MRI studies because it inadvertently ensures that only the largest—and thus, least likely to be true—brain differences end up passing the significance test and then being published.”

What that’s saying is that you can keep on testing a sample of 25 people looking for a social construct that without “scientistically correlating data” remains a social construct rather than a disease, and that as long as you up the correlation then it’s considered more accurate. In other words, one can go back to “hysteria” and women with red hair, and as long as one keeps testing samples of 25 long enough, and one finds after any number of tries, perhaps 800,000,000 that are all discarded till one gets a sample where 19 women with red hair all have “hysteria” that there’s a genetic correlation with the red hair gene and hysteria, but this wouldn’t be the case with 14 or 15 women out of 25. And it helps that there is a great difference of hair types, because if more people had red hair the sample would be more representative of the whole were all red haired people looked at, which doesn’t meant that that’s applied here, because then were a larger group available to test that would have to be used instead of whether any smaller group that’s separated from a larger group with the same variable does have said correlation when the correlation threshold has been upped to be used in the smaller group rather than that there’s no correlation in the larger group when the threshold is smaller. Neither could one dismiss any testing that doesn’t have the correlation, although with the same variables.

I’m just curious statistically at what threshold one would end up getting a correlation for anything remotely possible using a smaller group with an “increased threshold for statistical significance,” and at how many repetitions of a smaller group with an “increased threshold for statistical significance” one would eventually make any potential supposed “significant” connection. I mean potentially also, given that for some reason the rules haven’t been bent so much such that humans have said alleged disease (that without correlation only remains a social construct) because they are really monkeys or lower forms of life such as savages (this isn’t a statement against monkeys or savages), or that so and so has said disease because another “human or monkey or savage” goes flying around on a broomstick at night and has a friend with a tail, horns, and is quite red of complexion (although this “used” to be science, this is presently outdated?); I mean when is it possible to prove (using math and potential regarding probabilities) that a group of monkeys with type writers actually wrote Shakespeare’s plays (or the Bible) because this upped statistical threshold was repeated often enough. And would psychiatrists go looking for these amazing creatures given a time machine to go such trillions of years into the future where it would have somehow occurred or should this be illegal being that it’s abusive to the monkeys, or does it give the psychiatrists something better to do?

THAT way one could simply use math, and might discover that monkeys with type writers, given a trillion years or so could have written everything known to man, or (given probability theories) that when looking for “psychiatric” data enough amongst divergent groups one could make up any diagnosis one wanted to entertain, and with present psychiatric research find this “correlation.” And what limitations are there on this “scientism” given that sadness or grief are psychiatric symptoms, or not wanting to pay attention in school, or not conforming to social norms, or not wearing clothes, or being traumatized by trauma…..?

This REALLY is just amazing stuff….

WOW!!!!!

Thus ANYTHING unusual enough to occur in a small enough group, once under inspection enough to find a big enough correlation of anything that can be seen as a psychiatric disease: TADA this becomes a correlation at large!?

Report comment

I think the word you are looking for is “horseshit!”

Report comment

Yeah but “horseshit” is potentially fertile….

Let’s not insult animals. Give a gang of primates typewriters to type on, and considering evolution, before anything would come of it akin to the DSM, they might have evolved passed such discriminatory….. (I DID almost use that word now….)

or bulls….

I can’t believe this stuff, actually. It’s like an exercise in intelligence can one actually decipher how corrupt these “scientific” processes are that are exploited to make out it’s a “disease” when there are “symptoms,” exhibited by people not adapting or assimilating themselves to statistical based norms.

It took me awhile just to make out once again how they come up with technical sounding procedures in order to excuse promoting incoherent logic and data. As for example how when a pair of twins are both found schizophrenic, that their total is 4 because it’s two people with a twin, but when there’s no concordance (only one is “schizophrenic”) then it’s just 2. There’s another holy mumbo jumbo name given for that, as if it’s scientific. Or anti-depressant trials where most people have to leave the trial who are in the control group, because of bad side effects and they aren’t counted, and anyone in the non control group getting “better” within the first couple of weeks is dismissed and not counted, and people already on psychiatric drugs are put into the trials, and people with side effects of the anti-depressants are given sedatives while on the trial, and yet with all of that and more it’s only a marginal improvement whose effectiveness wanes off after a few years and there’s more recycling, and none of the trials with bad outcomes were reported, and earlier antidepressants always had better effect as do no drugs when a perspective on time or side effects are looked at. Or putting people already on and physically addicted to a substance in a trial for another such substance and when anyone in the non control group is having withdrawal symptoms that ANYONE on such a drug would have when abruptly taken off then it’s a symptom of the disease rather than withdrawal symptoms (by this time going over all of this I already have psychiatric symptoms because it’s overloading to try to remember all of it, let alone infuriating and saddening, and these lies are what anyone with a psychiatric diagnosis is told also, and would you know the truth it’s already extremely distressing and overloading having encountered such to be confronted with the same)… I have to clear my mind to remember what else I’ve already encountered (One lady I was a buddy to had been drugged up to find it made her catatonic and didn’t help and it took her years to be able to read a whole page and be able to cognate what kind of mumbo jumbo was going on when what made her sick was made out to be a cure)…..

Oh yeah, and how at first they tried to make out that clear signs of how their medications caused brain damage instead was a sign of the disease, which had to be straightened out against their will the same as the warning that anti-depressants can make people homicidal and or suicidal.

That all being only part of it, the “magic” of psychiatric drugs.

And in reality, you’re only dealing with normal responses to life that don’t fit with a fear based populace that are terrified of exhibiting signs of non conformity. And one isn’t allowed to articulately point out what’s going on with the “society” to begin with when it causes such normal responses that expose there might be something going on that needs attention.

What’s sad is when people are trying to still fit into such a society, even when they are rebelling against psychiatry. A society that uses fear based trauma as a mind control method thus making that out to be how one maintains harmony, and thus has a whole arsenal of people trained to traumatize others that are rewarded when they do so and thus can become pathologically mesmerized with hurting others and yet these people are used in order to “discipline” society, is it a wonder that such a “society” doesn’t acknowledge signs of trauma, even when it comes from behavior it says is illegal such as child abuse?

And then when things change without such a need of training others to “justly” traumatize others, this again isn’t acknowledged.

Report comment

True enough – horseshit at least can serve a purpose, while the DSM is useful only as a doorstop or extra TP or to start a wood fire in your fireplace. Maybe as a defensive weapon if attacked. It really has no productive purpose at all, and in fact is destructive in the extreme.

Report comment

Do not throw all brain imaging out, as some can prove brain damage and the worsening of brain function. (From WHAT?) Autopsy can prove brain changes to the dopamine transmit-receive functions.

A worsening of brain function would likely mean a stupider “patient” which is the opposite of what the psychiatrist claims they want.

The psychiatrist claims they want the patient to have an insight into their illness.

Report comment

Of course, brain imaging has its place and can be valuable. It’s just not valuable when looking at behavioral/mental/emotional/spiritual challenges. Finding that a particular area of the brain is “more active” or “less active” when someone is feeling depressed tells us practically nothing about causality.

Report comment