Mad In America and its writers are often dismissed out of hand as “anti-medication.” But we’re not anti-medication, we are pro fully informed choice. It’s just a shame that people in society don’t get anywhere near full information about how well drugs work or what their actual risks are. But a lot of this boils down to people not understanding the difference between aggregate and anecdote. There’s a lot of people out there who don’t want to hear medication critiques because they like their meds. And for people who like their meds (or like their family member on the medications), how do we reach them?

Of course there are many reasons that people don’t have the information to balance harms and benefits. A lot of these reasons are discussed on this site, such as institutional corruption, dominant society paradigms, or medical providers with conflicts of interest. What I wanted to go into today is the people who can’t hear any of this data because they don’t understand the difference between aggregate vs. anecdote.

1. “I like my meds.”

A lot of people say, “Well, my meds work for me, they were a miracle.”

My response is, “This sounds at first blush like a success story. This is why our messaging needs to be careful. The idea is that medication helps some people, but not everyone, and may be increasing the amount of disability in our country.”

This is because in the aggregate (that is, on average) the vast majority of medications are no more effective than placebo in the long run. But aggregate does not mean everyone. Just like any average of data, there are people who do well, or extremely well, or extremely poorly with any kind of treatment.

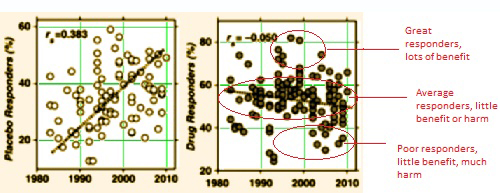

There is a very good blog post from the late great Mickey Nardo at 1boringoldman.com about how many drugs don’t even beat placebo. The image below is a little more complex. It is actually depicting how drug trials show a higher placebo response rate through time and a lower drug response rate. But notice how similar the placebo chart is to the drug response chart. This is how the aggregate can be visualized. Your success story is one of these dots. In this image, each dot is a whole clinical trial, which could break out into another clump of dots. This site is talking about all the dots. You can’t talk about all the dots until you look at all the data.

The vast majority of the data shows that people who benefit are statistical outliers. You got lucky. We’re glad you got lucky. But your story is not the whole story.

But what about the others, the ones who are hurt by the medication or it doesn’t beat placebo? Is it worth the risk? Public policy decisions shouldn’t be based on “the lucky ones,” they should take into account all aggregate data. And users who are statistical outliers shouldn’t promote their treatment as a solution for everyone. People who tell a story about one dot on that chart but then don’t listen to the story about all the dots. And there are many more dots on that chart that had no benefit or had harm than the ones who got lucky and were helped.

2. “But the drugs don’t hurt me…”

And then there is another version of the story. Have you heard that one yet as an advocate? If you are trying to share info about medical harm and your friendly drug user friend says, “Well, they don’t harm me….”

My response: You just may not know what you are missing. My personal recovery story included a time where medications seemed very helpful, but later the medications started causing a movement disorder and severe sleep disruption, both of which resolved when I came off medications. Also, many medication critics talk about “numbing emotions,” and I never felt numbed on medications. But when when I came off medications, there was an incredible emotional intensity and beauty to my life that I didn’t even know I’d been missing.

People may not know the harm being done.

People can be advised to work on reducing the medications that are causing the most problems with side effects, and work with an extremely slow taper according to good tapering practices found in this list of resources. Most people find a “minimum effective dose.” Once people know the difference between medication withdrawal effects and the return of the “illness,” many people find that the biggest effect of their medication is simply relief of withdrawal symptoms.

Back to anecdote vs. aggregate — you may be in the lower dots and not the lucky dots without even knowing it. And then there is the thing about our communities dying 25 years younger.

3. “What about suicide?”

But then some people say, “But the drugs keep me alive.”

My response: Well, the medications don’t prevent suicide in the aggregate in the long term. They may prevent suicide for you, as one data point, but the rest of the data points show that some of these drugs actually increase suicide.

Again, for individual vs. aggregate: Some lucky dots might feel that suicide has been prevented. But looking at all the dots, the risk is increased. Mickey Nardo did a whole series of posts on Robert Gibbons who fought the FDA black box warning on SSRIs. The FDA put the black box warning on SSRIs because they were increasing the suicide risk for youth. And Gibbons said, “FDA shouldn’t have done that because the kids might die by… suicide.” But Gibbons basically had to make up data in order to make his point. The FDA’s view of all the dots showed an increase in suicide.

Your “lucky dot success” story might be impressive, but good policy decisions are made by looking at all the dots. Again, anecdote vs. aggregate.

4. “Labels help people.”

There is a dude named Mark Weibe that has started to be my advocacy enemy here in Kansas City. He keeps saying, “I know you talk about harms vs. benefits, but what about people who feel relieved when they get their diagnosis?”

And I have told him, “Well, if the diagnosis was a valid medical entity that might be a useful point. But why trade long term stigma and disempowerment for short term relief?” And finally now there is starting to be more research on the damage done to people by psychiatric labeling.

Again, aggregate vs. anecdote. Mark may tell one story, one dot about one person who liked their labels, but I am talking about all the dots, all the people. Unfortunately, because I speak with passion, because I don’t always wear a suit, because I am not a white male, Mark gets heard in these rooms instead of me. His anecdotes outweigh my aggregate data because people are scared of conflict. They listen to him because he does the right butt kissing and he does not call out these emperors with no clothes. I’m sure that all advocates reading this have been through this experience.

You quote nine research studies talking about 30,000 data points and you care about the issue because you are tired of seeing your friends die. And some disease model guy who uses recovery language but not our concepts gets up and says, “Yeah, I haven’t read those studies but I know one person…..”

And they listen to him instead of you.

What do you about this? The challenger who says that the labels themselves help people? Especially in an advocacy setting?

5. “Well, you should support my CHOICES.”

Then there is this other misunderstanding of aggregate. People who say, “You are pro-choice for mental health, so you should support my choice to use psych drugs.”

My response: Well, it’s hard to support an uninformed choice that has been made on false assumptions. IF:

And you are not told this BEFORE you choose drugs and labels, then how valid was your ability to make that choice? We support people whose choices disagree with ours, but we do try to help people figure out where those choices may have been misinformed.

This is really the crux of this whole issue. Until the medication users and the disease model advocates feel “heard” by medical harm aware advocates, they aren’t going to listen to us. And I have such a heard time “hearing” them because they are so clueless. So they can’t hear me because I don’t hear them.

Dialogue is a two way street. I don’t know how to “hear” these people who LIKE their meds and don’t know any better. Give me some better ideas for these challengers in the comments?

6. “We have our ‘consumer’ input.”

And worst of all offenders who don’t understand aggregate are these ‘consumer’ coalitions. More and more funders are making coalition approaches mandatory to get funding. You know the type: 12 people at the table and one advocate if “we” are lucky. And you say, “We should have more people with lived experience at the table,” and they say “Oh, we do.”

Meaning: “We are going to count the long term admin people who now feel safe enough to come out with their recovery story.” Meaning this admin person is a novice advocate who has not been an advocate before and has not interacted with the advocate community and does not know the perspectives and viewpoints of the advocates.

Or: “We are going to grab some random patients off the clinic floor and say that they are the voice of the ‘consumer.'”

And that results in a completely deadlocked discussion group.

Well, guess what? Advocacy is skillset, advocacy is a profession, and inexperienced advocates are not a good replacement for experienced advocates. You know why? Because anecdote vs. aggregate. These novice advocates don’t know long term outcomes data in the industry, they don’t know about all the dots. And without experienced advocates at the table nothing new is going to happen.

And how do you fight this? When more and more voices “at the table” are blocking or excluding experienced advocates? The #6 challenger who is a high level decision maker, a coalition leader, and STILL doesn’t know the difference between anecdote vs. aggregate?

How do you fight any of this? Give me some fresh ideas in the comments below. How do you educate people about aggregate vs. anecdote?