Authorities throughout the world have warned against using depression pills for children and adolescents after the FDA had shown in 2004 and 2006 that these pills double the risk of suicide compared to placebo in the randomised trials.1 2 We know the mechanism of action for this effect. The pills can cause akathisia (an extreme form of restlessness that predisposes to suicide, violence and homicide), emotional numbness and psychosis.

Denial of the pills’ increased suicide risk

Despite the unambiguous findings and the authorities’ warnings, Lundbeck, other drug companies, and leading psychiatrists have tried for years to convince the population of the opposite — that there is no increased risk of suicide, and, on the contrary, that the pills protect against suicide. They have done so by referring to unreliable research or by selective citation of research that shows the opposite of what the psychiatrists claim.

We have seen this denial in many countries, and it has resulted in many suicides, not only among children and adolescents, but also among adults.

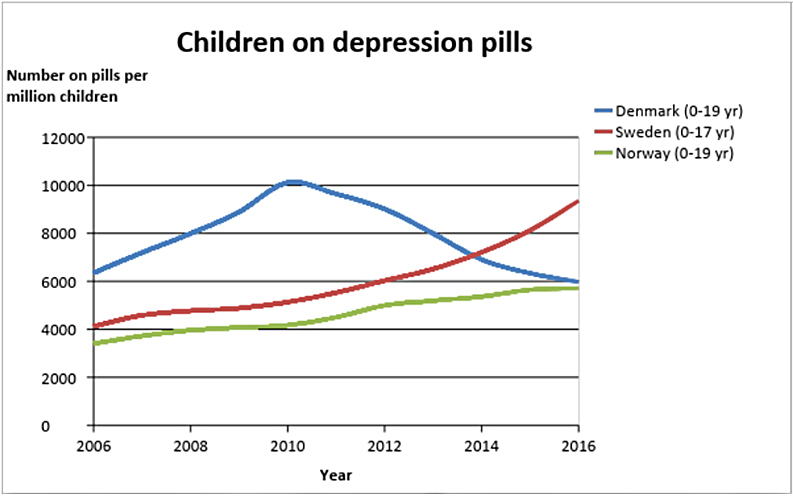

The consumption of depression pills decreases, but only in Denmark

After a number of years with a steadily increasing sales curve, the number of children and adolescents in treatment with depression pills decreased by 41% in Denmark, from 2010 to 2016.3 In the same period, the number of children in treatment in Norway increased by 40%4 and in Sweden by as much as 82%.5

The dramatic difference between Denmark and the other two countries is not seen in other therapeutic areas. The main reason is likely that, in the summer of 2011, the Danish National Board of Health issued guidance that GPs should no longer write prescriptions for depression pills for children, which should be a task for psychiatrists.6 Such limitations in the right to prescribe have not occurred in Norway and Sweden.

A contributory reason might be that, also in the summer of 2011, I began to warn strongly against the suicidal effect of the pills,7 which I have done countless times ever since in radio, TV, articles, books8 and lectures. No one in Norway or Sweden has done anything similar. The reason that it is particularly bad in Sweden is probably because of an influential psychiatry professor, Göran Isacsson, who, in countless articles, interviews and in unreliable research, has claimed that depression pills protect children from suicide. A contributing factor could be that the Swedish doctors who write treatment guidelines have financial conflicts in relation to the companies selling the pills. This is not mentioned in the guidelines.9

Despite the welcome development in Denmark, the denial of the facts by Lundbeck and several psychiatry professors has been — and unfortunately still is — very pronounced, which the rest of this article is about.

Radio interview with Lundbeck in 2011

The deception starts in the pharmaceutical companies selling depression pills. They have cheated massively, among other things by excluding many suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts and suicides from their published clinical trial reports.

On May 12, 2011, the then CEO of Lundbeck, Ulf Wiinberg, made a series of spectacular claims in a radio broadcast. The broadcast was about the fact that Lundbeck’s American partner, Forest Lab, had paid over $313 million in fines for bribery of doctors and illegal marketing of depression pills for children, and for withholding results that demonstrated harmful effects of Lundbeck’s drug. Forest negotiated compensation for 54 families whose children had committed or attempted suicide while being treated with Lundbeck’s pills.

In the broadcast, journalist Solveig Bjørnestad asks why Lundbeck does not discourage the use of depression pills for young people if there is an increased suicide risk. Wiinberg responds that it is not Lundbeck’s pills but the depression that leads to suicide.

The Director of the Danish Institute for Rational Pharmacotherapy in the Danish Medicines Agency, Steffen Thirstrup, considers the high consumption of pills among children and young people frightening, not least because Lundbeck’s medicines are not approved for children and adolescents, which gives Lundbeck a moral responsibility.

The chairman of the GPs organization, Henrik Dibbern, explains that a very crucial factor for the high growth in consumption is marketing by the pharmaceutical industry, on which the industry spends very large sums, and industry-sponsored medical education, which also affects doctors.

Wiinberg mentions that 40 Danish children committed suicide during a 5-year period and that none of them were in treatment with Lundbeck’s drugs (see more about this below). He also believes that there is no evidence of an increase in suicides, and that what is mentioned in the clinical trials is suicidal ideation. He claims that there is no link between suicidal thoughts and suicide, says that suicide attempts are not the same as suicide, and claims that use of the products actually reduces the number of suicides.

Wiinberg claims that Lundbeck does not market the pills for children and adolescents. But we know that Lundbeck’s partner did do this in the United States. We do not know what the drug salespeople have told doctors in Denmark during their “consultatory visits,” but we do know that 52% of GPs in Denmark who have received sales visits have experienced that the salesperson mentioned that the drug could be used outside the approved indications,10, although it is illegal to say this.

When Bjørnestad asks for an explaination of the marked increase in the consumption of pills for children and adolescents, Wiinberg replies: “I think there are doctors and parents who feel that when you have a seriously ill child, you want to do something for it.”

On Bjørnestad’s question about whether Lundbeck will advise GPs not to use depression pills for young people under 18, Wiinberg says that Lundbeck does not market the pills for children. Bjørnestad gets nowhere, even when she asks whether Lundbeck will insist that their salespeople discourage the use of depression pills in children. Wiinberg replies, “It is important that these children receive treatment and that it is prioritized because they are ill.”

The Evening Show 2013 on Danish national TV

On April 15th, 2013, I was on the Evening Show together with professor of psychiatry Lars Kessing. Like Lundbeck, Kessing claims that depression pills protect against suicide, and he emphasizes that this is something we know with very great certainty.

Kessing mentions that the number of annual suicides in Denmark has fallen from over 2600 in the early 80’s to 600 while the consumption of antidepressant drugs has risen.

Kessing also says that there is a substantial difference between suicidal thoughts and suicides, but it is very misleading to separate the two. Suicide starts with suicidal thoughts that lead to suicidal behaviour, suicide attempt and suicide, and there is of course a connection between these things.11 12 13

Kessing mentions one of his own studies,14 which is undoubtedly the same study that Wiinberg mentioned. Kessing says that there wasn’t a single suicide in a 5-year period among 2600 children and adolescents in Denmark who had received SSRIs (so-called happy pills) whereas there were 41 suicides among children and adolescents who had not received antidepressant drugs. Kessing also believes that depression in children and adolescents is underdiagnosed and undertreated and that they perhaps committed suicide because they were not diagnosed.

Kessing’s information is highly misleading. Since SSRIs were not approved for children in the study period (1995 to 1999), it is not surprising that those who committed suicide had not received an SSRI.

In Kessing’s study there was also a 5-year follow-up, which he did not tell the viewers about. Now many of those who committed suicide were on SSRIs. “Those treated with SSRIs had a highly statistically significant and strongly increased rate of suicide compared to those not treated with SSRIs” (19 times increased risk).

Kessing was on Lundbeck’s payroll, and the study was funded by the Lundbeck Foundation. The result didn’t look good for Lundbeck’s drugs, and the authors presented another analysis where they had corrected for psychiatric hospital contact. The risk was still increased, 4 times, but it was “no longer quite significant.” It is extremely misleading to correct for psychiatric hospital contact, as such contact in itself increases the risk of suicide for psychiatric patients 44 times.15 A correction will therefore spuriously attenuate a true link between SSRIs and suicide.

The authors found that SSRIs dramatically increase the risk of suicide in children, but they concluded the opposite: “not treating severely depressed children and adolescents with SSRIs may be inappropriate or even fatal.” What may be fatal for children are psychiatrists who conclude like this against their own results and use SSRIs in children and adolescents.

When I mention on the Evening Show that the National Board of Health warns that the drugs cause suicide in children and young people, Kessing says it is “plain nonsense” what I say and “plain nonsense” what the National Board of Health says.

Jyllands-Posten 2018

On February 4, 2018, a Danish newspaper published a comprehensive report about a 19-year-old boy’s tragic suicide on depression pills, which he got for sleeping problems.16 Both the parents and I are convinced that it would not have happened if their son’s GP had not given him depression pills.

I wrote in an accompanying paper17 that depression pills have no relevant effect on depression and that they increase the risk of suicide not only among children and adolescents but also among adults.18 19 And that psychotherapy halves the risk of a new suicide attempt in people admitted to hospital after a suicide attempt, which means that patients should receive psychotherapy and not pills.20

Nevertheless, two leading professors in psychiatry, in the same newspaper, tried to maintain the myth that the pills actually prevent suicide.

Poul Videbech wrote that “for children and adolescents there was a possibly [my emphasis] slightly increased risk of suicidal thoughts and acts but not for suicide.”21 The analysis referred to by Videbech found a doubling of the suicide risk for children and adolescents and not a “possibly slightly increased risk.”

Videbech also mentioned the Danish study, both in his article and in an interview. Like Lundbeck and Kessing, Videbech mentioned that none of the 42 young people between 10 and 17 years old who committed suicide were in treatment with SSRIs. Videbech did not point out that this study in fact confirmed that SSRIs cause suicide, but gave the readers the opposite impression: “Hence you can believe, but will never know, that so many suicides would have been avoided if treatment with antidepressant drugs had been more widespread.” It is quite irresponsible to claim that pills that increase the risk of suicide should be able to prevent all suicides.

In the newspaper report, child and adolescent psychiatrist professor Per Hove Thomsen also misled the readers in his defense of the pills. He felt it gives food for thought that in a period when the consumption of happy pills rose in Denmark, the number of suicides dropped from around 1500 to 700. Such data cannot be used for anything. Falls or increases in suicides have many causes, and in the United States (and in several other countries) suicides increased markedly in the same period where the consumption of happy pills also increased markedly,22 but the psychiatrists never mention anything about such data.

The chairman of the Danish Society for General Medicine, Anders Beich, said that the long waiting times for psychiatrists can be catastrophic because it is dangerous to have a depression, which in itself can lead to suicide.

What’s catastrophic is not the waiting time for psychiatrists, as many doctors, psychologists and others offer psychotherapy, but that my colleagues are wrong in their views. The meaningless suicides caused by depression pills will continue for as long as the pharmaceutical companies and the leading doctors continue to deceive the population into believing that these pills protect against suicide. I do not understand how it is possible for both Lundbeck and two psychiatric professors over a period of seven years to quote a Danish study as selectively and highly misleadingly as they do. Why do they protect the pills instead of protecting the patients? It is horrifying.

Make it illegal to use depression pills for children and adolescents

Despite the guidance from the Danish National Board of Health, there are unfortunately still many GPs who prescribe happy pills for children and adolescents, and it also happens without contact with a psychiatrist. By 2016, 5,560 young people aged between 18 and 24 received their first prescription for a depression pill, and in 55% of cases, the GP started the treatment.

Depression pills have no beneficial effects in children and adolescents, and they have many other serious harms besides suicide, but unfortunately they continue to be used by children and adolescents. Therefore, the National Board of Health should issue a guideline saying that no one, psychiatrists included, should prescribe these pills for children and adolescents. Of course the most effective measure would be to prohibit by law the prescription of depression pills for children and adolescents.

I owe it to Danilo Terrida and Rasmus Burchhardt, who both hanged themselves, only 20 and 19 years old, respectively, after their GP had put them on happy pills, for which there was no indication at all. I have written about them because their families wanted me to do so in the hope that their own meaningless loss could help other parents realize that they should never, ever allow their children to be treated with a depression pill.

If you are already in treatment, do not suddenly stop. It can be dangerous due to abstinence symptoms. Get professional help for tapering, for example, via www.deadlymedicines.dk or www.iipdw.com.

“Wiinberg responds that it is not Lundbeck’s pills but the depression that leads to suicide.”

We need to nail these drug companies on Akathisia. Maybe Kessing and Wiinberg would agree to having Akathisia induced so they can experience this horrific torture. Not only should it be illegal to give these pills to children, they should be locked up for doing so.

Keep up the good work !

Report comment

The message about poor efficacy and suicide risk for children appears to have got through directly to professionals in Denmark.

But for adults it is far from clear whether very black and white ‘depression pills cannot cure anything’ ( http://www.madinamerica.com/2018/01/antidepressants-effect-depression/ ) messages will work, or even be counterproductive: https://drnmblog.wordpress.com/2018/04/18/pillshaming-is-real-heres-a-newish-way-to-reduce-it-and-to-reduce-antidepressant-use/

Report comment

Dr. MacFarlane, I read your post. With all due respect, psychiatrists as a whole seem happy with shaming patients to defend the integrity of the precious pills they dish out to as many folks as possible. I suffered shame for many years on these happy pills. Why?

They were “safe and affective” so I was faking any problems they caused–seizures, fatigue, depression. Moreover I must be malingering since none of these magical treatments helped me live a happy, productive life.

Pills don’t feel shame. Patients do.

Psychiatrists bad mouth the gullible folks who came in desperation, to their families, “Rachel is obviously not taking her ‘meds’ or she would feel wonderful and act normal.” “Haldol never causes seizures. She’s faking it.” “Risperdol doesn’t cause weight gain!” “Antidepressants restore the chemical imbalance in the brain, so Rachel isn’t trying hard enough. Being maligned as bipolar so she can’t find work/housing/relationships has nothing to do with her unhappiness.”

Research should be done on how many cases of “bipolar” are created by reactions to the use of SSRIs for depression, obsessive thinking, or off label uses like bed wetting. But it might lead to #pillshaming. We can’t have that.

It’s okay to shame patients. #Pillshaming is the unpardonable sin!

Report comment

Rachel…I am pretty sure that I have come across all that you describe in my clinical experience. It is implicit in my piece that people should be told about 1. efficacy & placebo effect 2. potential harms. Unfortunately the linked problems of Pharma & psychiatric self-interest prevent us giving good figures for either, and if we carry on denying the reality of pillshaming they will be able to distort it in the way(s) you suggest.

Extreme statements such as ‘depression pills can’t cure anything’ seem to come across very often as ‘depression doesn’t exist…maybe you’re malingering’.

Of course not all discomfort can be eliminated, but I am questioning how effective the statements of Gotszche & others are, as much as how accurate they are.

Report comment

Please correct me if needed, but you do mean as in: if this arguments can hold up to any possible counter-arguments that could be presented?

Report comment

Mr. MacFarlane, I am trying to think what I would do if I in good intention write a code that would turn out a virus and harm many systems, some of them life-supporting, around the Inet connected world. How would I safe my face, because if as a woman I would just start crying and pledge for forgiveness, I would be out of business forever and my voice lost… Allthough I am still the capable programmer I am. Therefore, nobody is helped and my talent lost. Maybe I would contribute a brilliant idea how to solve the issue I myself started… Is there any such brilliant psychiatrist available? Or could we start a contest with good money for the prize (technicions like getting paid well) that gives psychiatrist a motivation to figure out something helpful? While psycholigists get the time they need to study maths and whatever they need? Sorry for this maybe weak idea but I very much like to get psychiatrists on board to finally end all this immense suffering…

Report comment

So you test something against nothing… Thats always zero in my logic. If I have an effect of 10 and do minus 0 its still 10. And then the next drug would have effect 5 and I test it with minus 0, ah, effect 5. But because I don’t know the effect size because thats why I do the test… Well I have SSRI 1 with an unkown effect size and SSRI 2 with an unkown effect size. Thus the study was very expensive but did deliver no result at all. Can you elaborate on that??

Report comment

After a glimpse on your blog I ask myself how can a pill have a ‘placebo’ effect? I understand all that belief thing, but it makes no sense to me regarding the functionality itself. The pill has an effect on the brain, there is no debate on that if I am correct. So its something about Serotonin, but its not simply producing more but inhibiting uptake meaning in most systems it would cause…?… more production of Serotonin or whatever… So, its somehow usefull for those (now a psychologist would be of help) that need to get focused, like with a lense, but who can use that focusness. For many it might be too overwhelming to suddenly get a clear picture of their problem… Which might make the freak out in horror like you see the monster in front of you clearly for the first time – – > flee this reality, ergo psychosis… Others might get so excited with that clear sight that they get manic (but sort of forget to use this state of consciousness to solve their respective problem or they somehow can’t do it because of complexity or whatever)… So the brain constantly adapts and therefore no chemical can stay functioning for long, but there are various SSRI therefore one could cheat the brain for a while by switching the SSRI.. But never forget the other bodily systems that get influenced and the longer the mor compkex the issues…. I came to that conclusion because of the ‘shame’ in pillshaming especially in case of antidepressant… So the root cause of depression is shame? Someone’s shame within the system of the patient not necessary him- or herself… An ‘antipsychotic’ is different in its effect… We psychotics talk very angry about the suppression and oppression. That we received. We were silenced. By society and/or ourselves. For what?… See, a bit of calm reasoning can maybe lead somewhere?? Or is it bullsh**?

Report comment

Maybe a child can just not handle such an immensely focussed state? Childhood is about a dreamy safe place full of fairytales. Its hard enough to become an adult and fathom the way people treat each other in this world. Why force this type of consciousness state on children? Are adults today that wrecked that they cannot handle ‘unrational’ children anymore?

Report comment

Phoenix…yes, children should be medicated as little as possible. The ‘placebo effect’ is so strong with ‘antidepressants’ that new drugs have always been tested against ‘sugar pills’, rather than existing drugs.

Report comment

What if taking the SSRIs leads to accusations of malingering when they don’t have the desired effect?

For my part, I found the notion that psychiatric drugs don’t work to be an immense relief. An end to shame.

I was not hopelessly insane/morally defective after all. And my prolonged depression (10+ years) was caused by the pills that were supposed to help me.

The truth will set you free!

Report comment

You are telling the truth.

Report comment

As far as “depression does not exist” I would have to disagree, Dr. MacFarlane. We are on the same page there.

I have had fits of prolonged unhappiness since I was 7. Partly school problems. I had behavioral issues and was put in a class where I was yelled at for knowing more than other kids. (A foretaste of my adult life as a career mental patient!)

Because I couldn’t verbalize my distress–smart though I was–I became so gloomy I willed myself into developing influenza for 3 weeks in a row. I wasn’t learning jack at school anyhow.

If someone is depressed they may have something bad in their life they need to deal with. An emotionally abusive relationship–a job they hate. Maybe it’s something they can’t change but need to come to terms with. They may also be anemic or have thyroid problems.

I’m not anti-therapy. If someone is discouraged or sad, yelling at them can be very cruel. Love, support, and hope can cure depression along with proper diet, sleep, and exercise.

An SMI diagnosis leads to rejection, isolation and hopelessness. It got me kicked out of college and prevented me from ever marrying or having a family. I live in crushing poverty since I can’t drive or get a job. Pretty depressing!

Report comment

What I described is NOT “pill shaming.” Rather the pills were defended and glorified by shaming HUMAN BEINGS #Patientshaming!

Report comment

Not sure why “depression pills can’t cure anything” leads to “people claiming to be depressed are malingering.” People DO feel depressed, sometimes severely, sometimes for a long time. No one is denying this reality. The problem is calling “depression” a “disorder” implies that it is ALWAYS caused by the same thing, is ALWAYS pathological, and is “curable” by these pills in most or all cases. You and I both know that none of these three statements is true. It is VERY easy to say, “Depression as a state of mind exists and can be extremely painful. However, efforts to “cure” depression with pills have not been effective.” These two premises do not contradict each other in any way.

Report comment

“Why do they protect the pills instead of protecting the patients? It is horrifying.” I couldn’t agree more.

Congratulations on lowering the rate of child drugging in Denmark, Dr. Gøtzsche, and thank you for speaking the truth about this dangerous class of drugs. It’s so sad that grown adults have sunk to the level of giving young children dangerous, mind altering, psychotropic drugs on a massive scale, merely because it’s profitable. It is horrifying.

Report comment

Amazing, Rachel, really. #Pillshaming! And sorry for my heated reaction on one of the other threads.

Report comment

Phoenix, you were right that I don’t know what it’s like to have a child “out of it.” I feel bad about what I put my own family/friends through. Part of it was grief over my lost life; part being under the influence of drugs 24/7.

I didn’t start out “psychotic” but depressed and very anxious. (Later psychologists said I had PTSD, for what it’s worth.) Anafranil ,made me loonier than Minnesota in the spring. And all my earthly hopes and dreams were cheerfully crushed by Dr. M. my shrink when he told my mom I was “schizophrenic” but it COULDN’T be the Anafranil since it NEVER had that effect on anyone.

Later they fed us the BS that it was my fault. I must be a defective or that life nourishing, wholesome goodness would never have made me loopy. Therefore since my illness had been “unmasked” I must attone for my sin of being SMI with endless doses of cocktails, infantilizing “clubhouses” and other crap. Here’s the question nobody asked: Since Anafranil unmasked my MI and all psychiatry offers are treatments to remask the alleged brain disease, why not just take me off the d___ed drugs?

Hence my premise that when folks (mostly shrinks, though some frightened psych patients also do it) yell #pillshaming they are really honoring the pills at the expense of those disabled by them. Also my complaint of #patientshaming.

Off my whole cocktail and no longer manic or depressed. No thanks to any medical professionals I know. 🙁

Personally, I mean. Dr. Peter Breggin’s advice has been very helpful. I love that man.

Report comment

I suggest that Gotzsche, judging from his books, understands a lot more than you care to admit. I am extremely disatisfied with the way doctors win illicite sums and other perks by prescribing what are, more than you tell us, potentially lethal drugs. It’s proof that because your à doctor does not necessarily mean an intellectual competence superior to that of other less socially advantaged citizens.

Report comment

What good is a superior intellect with no conscience? It only makes one more of a menace to society than a nasty guy with an IQ of 75 who mops floors for a living. At least he’s less capable of hurting people.

Report comment

John Herbert…yes, Gotzsche is a major researcher. If you look at his recent article on ‘antidepressants’ (the first link I gave, above) the title says ‘It’s Unlikely That ‘Antidepressants’ Have a True Effect on Depression’. But towards the end he writes ‘depression pills can’t cure anything’. There is a big difference between the two which, for me, undermines his credibility.

Report comment

In cosy central Europe we have it a bit sloppier than on your island, Mr MacFarlane, we allow for a middleway, that’s why we let yourselves decide to leave but still grief your island drifting off more and more… We are a bit less linear…

Report comment

Another thing, psychiatrists have always been vocal about “No cures; only treatment for mental illness.” In that respect, Dr. Goetzche is only saying what they have said all along.

Telling people they can recover from depression and other problems would make some angry. Others might find it hopeful and empowering.

The people who will really be angry with you, should you choose to denounce “antidepressants” as safe and effective, Dr. MacFarlane, are your colleagues and many other professionals making a fortune off of “mental illness.” Your fears are rational, and I admit to being a coward myself. At least you can’t be locked up without committing a crime.

Report comment

Goetzhe undermines the credibility of psychiatry. That’s what really rouses MacFarlane’s ire.

Report comment

Do you accept that these drugs harm to the point they kill people..heart failure, dementia, akathisia induced suicide/homicide or for you they do not do that ?

Report comment

For Dr. MacFarlane they don’t. When he prescribes pills for his patients HE never suffers extreme weight gain, cognitive problems, suicidal thoughts, etc. For HIM they work perfectly. And “diagnosing” someone as incurably insane doesn’t lead to people treating HIM like a monster.

Report comment

I doubt you’d find a mainstream psychiatrist anywhere who claims that antidepressants cure something. They will almost universally say that they are “treating symptoms” but that there “is no cure.”

Report comment

Dear Dr Gøtzsche,

I have to be straight on this, people that promote potentially fatal drugs as safe, are Psychopaths.

Report comment

Don’t pathologize it. It’s a moral issue–not organic. They are liars. And in the case of the “silver backs” as Dr. Gotzche calls them, they are brutes who don’t care about other people. They seared their consciences since they got in the way of career advancement.

And they go on the air telling everyone how dangerous we are–how we lack empathy and moral consciences. Disgusting!

Report comment

I think Psychopath is a reasonable description.

Report comment

I would describe this Olanzapine death and it’s interpretation as Professionally Psychopathic as well.

https://www.inquest.org.uk/oliver-mcgowan-conclusion

I believe UK Prime Minister Theresa May has implied the same with her inference concerning the “sub human” Medical Approach to the care of the “Mentally Vulnerable”.

Report comment

Psychopathy is a ‘descriptive’ term for (quite freely interpreted) someone who blinds out emotional/intuitive input or who doesn’t value emotional knowledge much but only relys on their (rational?) mind for reaching conclusions and making decision. Wether there is something in your system (or brain) that enables such a way of perception or its something you learn or ‘train’ your brain to do, isn’t the most important factor or it can be the most important one, depending on what topic you are on (try to think like a judge in law now who decides if somebody did it on purpose or for some – sound? – reason or couldn’t do else because of his nature).

Report comment

‘It’s Unlikely That ‘Antidepressants’ Have a True Effect on Depression’

‘depression pills can’t cure anything’

Both those statements are true. Antidepressants surely don’t cure a condition, no-one in their right mind would say that. The subtler question is whether they have a true effect on depression, and from the meta-analyses of the drug companies own studies, I’d have to say no, they are active placebos. The effect sizes and number needed to treat are simply inadequate – furthermore, it looks like there isn’t a coherent theory for why they would.

Report comment

They “work” on the same principals as LSD from what I have read. Street drug uppers could be just as effective at curing depression.

Report comment

But they are placebos with deadly effects. There are not only the physical effects that we all know about but they affect thinking and decision making. When I was on huge doses of Effexor I began doing crazy things. I’d be walking down the sidewalk next to a busy street filled with traffic when all of a sudden I’d wonder how “lucky” I was that day and bang a right turn out into the street. Thank goodness the drivers in the cars on those days were alert and paying attention or I’d be dead. I made a lot of people upset with my behavior and they had a right to be angry at me. I was a zombie separated from my emotions and feelings.

I will never take those damned devil’s tic tacks ever again.

Report comment

1) Antidepression pills are poison, see for example fluoxetine (prozac) – https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/3386#section=GHS-Classification&fullscreen=true

2) Administering poison instead of medicine (that should be non harmful) is a crime and must be prosecuted. It is maltreatment instead on treatement, injuring people with pills, even killing people with those pills.

3) It is a shame that psychiatrists like you promote the discontinuation of prescribing these pills for adolescents and children while normal grownup people should still receive them ? You should promote a complete ban on prescribing these toxic substances so we can all stop being tortured.

Report comment

I respect Dr Gotzsche as a researcher but the issue is what will work at a societal level.

I respectfully ask commenters to read the pieces about depression on my Blog. My goal would be to reduce ‘antidepressant’ prescribing (in adults) by 90% over, say, five years, and keep reviewing the evidence.

Dr G may have achieved this limited success in his own Danish back yard, but he is largely ignored by the BBC and mainstream media in the UK. Even he must be thinking there might be something about the way he puts his research across.

Report comment

See below

Report comment

I don’t think that being reasonable and appealing to the better side of psychiatrists who prescribe these drugs is going to work. It hasn’t worked so far. Dialoging and being reasonable and saying things so that these people will listen doesn’t work. The public doesn’t seem to be listening either.

You realize that the slave owners here in the United States were not open to dialoging and having rational discussions about how it was wrong to own human beings. Dialoging and being rational led nowhere with those slave owners. They had to be forced to free the slaves through a horrific war, a war which killed more Americans than in all the wars that we’ve fought, before or since. They had to be forced to do the right thing. Psychiatrists are not going to quit giving these damned drugs to people just because we are rational with them. The public is not going to quit taking them simply because we lay out a rational explanation for why they shouldn’t take them or allow their children to be forced to take them. Being rational isn’t going to work!

Report comment

Slave owners accused the abolitionists of great cruelty.

If you opposed slavery you hated African Americans according to the slavers.

#Slaveshaming no doubt. By opposing their Peculiar Institution you were being mean to the slaves needing their whips and chains.

Report comment