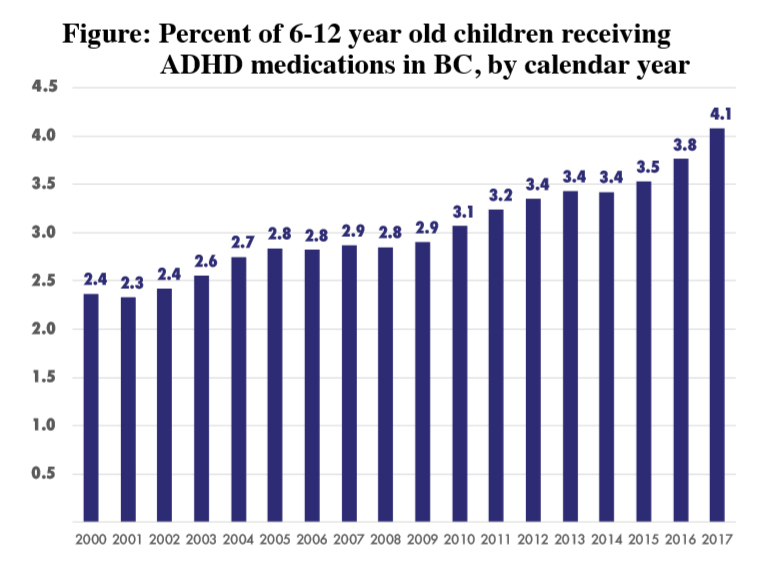

A new study, published online in Therapeutics Initiative, finds that despite published, replicated evidence that the youngest children in any given classroom are overdiagnosed with ADHD and overprescribed stimulants, prescribing rates for children in British Columbia have continued to increase.

The Therapeutics Initiative is an organization in British Columbia, Canada, that is funded by the government through a grant to the University of BC. Their mandate is to update clinicians and agencies regarding evidence-based use of psychopharmaceuticals. Their mission is to provide healthcare evidence independent of industry.

In this letter, they write that at least six different studies, in different countries, have found the same result—that the youngest children by birth month in any given classroom are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD and prescribed stimulants. Some studies found that younger children were up to twice as likely to receive the diagnosis compared to the older children in the classroom. A study in the US concluded that “roughly 20 percent of the 2.5 million children (in the US) who use ADHD stimulants have been misdiagnosed.”

In a 2012 publication in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, researchers in British Columbia found that “Boys who were born in December were 30% more likely […] to receive a diagnosis of ADHD than boys born in January. Girls born in December were 70% more likely […] to receive a diagnosis of ADHD than girls born in January.”

Therapeutics Initiative has published two previous official letters analyzing the data on risks and benefits of psychostimulant use in children: in 2008 and in 2009. In both cases, they recommended much more cautious prescribing for children. They noted that there are significant risks to stimulant use, including insomnia, weight loss, cardiovascular problems and growth problems. They also noted that although stimulants increase parent and teacher ratings of behavior, they demonstrated a lack of efficacy at improving academic performance, and did not improve the child’s anxiety. They had no effect on delinquency or substance abuse after 3 years, and longer-term measures of success and health were nonexistent.

Given these papers, and the consistently replicated finding that younger children are misdiagnosed and overprescribed, the researchers expected to find a decrease in prescription practices. Instead, they found a continued increase in the prescription of stimulants to children.

In their current paper, the researchers drew the following conclusions:

In their current paper, the researchers drew the following conclusions:

- “Whether the benefits of long-term […] stimulants for ADHD in children outweigh the harms remains unknown.”

- “There is convincing evidence that a proportion of boys and girls treated with stimulants in BC and around the world are simply the youngest in their class.”

- “There is insufficient evidence to know whether our publications or research findings had an impact on the overall rate of stimulant drug prescribing in BC children.”

- “The recent increase in CNS stimulant prescribing in BC is unexplained and concerning.”

*

Although Therapeutics Initiative is not technically a peer-reviewed publication, the disclosure at the end of the article states: The draft of this Therapeutics Letter was submitted for review to 75 experts and primary care physicians in order to correct any inaccuracies and to ensure that the information is concise and relevant to clinicians.

****

Therapeutics Initiative (2018). Therapeutics Letter 110: Stimulants for ADHD in children: Revisited. ISSN 2369-8691 (Online). Retrieved from https://www.ti.ubc.ca/2018/05/28/110-stimulants-for-adhd-in-children-revisited/ (Link)

They claim that the increase in stimulant prescriptions is “unexplained.” But it is easily explained! When you start with a “diagnosis” that has no objective criteria to “diagnose” with and which has no boundary between it and “normal,” and you add a drug which provides both a financial incentive to the prescriber AND a social incentive to the parent/teacher looking for a prescription, you have a formula for an ever-increasing rate of “diagnosis” and prescription.

One thing that would help is if we stopped saying “overprescription” or “overdiagnosis” and we started saying “unjustified drugging” and “malpractice.” These euphemisms make it seem like it’s just a little “whoopsie” instead of a massive and continuing abuse of both a “diagnosis” and a drug that are being used mainly to control unruly or active kids for the convenience of the adults involved.

It is also important to add that this trend toward increasing “diagnosis” and drugging flies in the face of decades of long-term studies showing that the kids who receive stimulant drugs do not improve in any long-term outcome area relative to other “ADHD” kids who are forced to take stimulants only in the short term or not at all. Given the clear risks that giving a kid stimulants entail, there is no excuse for this continuing malpractice.

Report comment

It would also help, Steve, if the root of the problem would be addressed. For instance, many kids diagnosed with ADHD are simply bored and thus act out. If schooling was catered to individual needs, many kids would be able to successfully complete school without being disruptive. Also, if kids received adequate psychotherapy when there is emotional outbursts or behaviors present, that would be preferable over using stimulants. These kids’ brains are still developing and I have to wonder what harm is being done by giving them drugs at such early ages. I would further argue that many children are growing up in traumatic or stressful households, so if this issue isn’t addressed by communities and families, we will continue to see kids display emotional and behavioral problems in the school setting.

Report comment

Very true. The first mistake is assuming that all “hyperactive” kids have a problem, and then assuming that they all have the SAME problem, and then assuming that the problem lies in the CHILD (or more specifically, the child’s BRAIN). None of these assumptions are supported by even a slight degree of evidence. Catering to individual needs is, indeed, the answer, but that would require the adults in charge to take responsibility, and it is SO much easier to blame the kids, especially when billions in profits are to be made into the bargain.

Report comment

Unfortunately parents are also conditioned to blame their kids rather than looking at their contributions, such as poor boundaries, unhealthy communication patterns, inconsistent responses from parents, addiction, etc. Kids need a safe, consistent environment to develop in a healthy manner. Schools also label kids inappropriately. I was labeled incorrectly by my grade school until my mother advocated for me.

Report comment

Too true! ADHD is all about letting adults off the hook and forcing kids to adapt to adult needs. The exact opposite of what is really appropriate.

Report comment

I agree wholeheartedly. I have 2 boys (now adults). Both boys knew how to read and write before entering kindergarten. Both were accused of having ADHD. They were so smart and social it was not to be tolerated. With the first boy I told the school where to go and that was that. The second son 12 years later I wasn’t so lucky. I was forced by the school

to take him to a psychiatrist who after 25 minutes of my son and I sitting in front of her not even flinching; wrote a prescription for Ritalin and we left. I gave my son a vitamin every morning so if the teacher asked he could say he took a pill. I wasn’t about to drug a healthy kid! Long story short, the grades improved along with the comments from the teacher about my son’s behavior on his report card. It was 6 months later I was on the school playground watching my son play during recess when his teacher came up and said “Isn’t it wonderful how the drugs have improved his behavior?” I turned to her and said “I never gave him the drugs; not once. You have been grading a drug free student…” The look on her face told me I shouldn’t have done that. After that his report card went back to he being about disruptive behavior and all the previous stuff she said. So sad how our teacher’s are indoctrinated to drug our kids and kill their creativity. He survived and is thriving. I don’t understand how this epidemic of diagnosing our kids came from. I know the schools get extra money but come on. Truly tragic…. What I really don’t understand is how can the parents go along with it! Thank you

Report comment

My comment was in reply to Steve McCrea’s comment.

Report comment

I have heard more than one similar story. The amazing part to me is how the teacher suddenly starts reporting problems when they realize the kid isn’t “medicated.” Talk about confirmation bias! Are they that stupid that they can’t see and admit that they were wrong? They just TOLD you how much he’d been improving! I guess being “right” is sometimes more important than actually meeting the kids’ needs. Disgusting!

Report comment

Well said, Steve. I will just add that anyone that believes mass drugging millions of children with amphetamines, drugs chemically identical to cocaine, would turn out to be beneficial to those children is stupid. Why today’s medical community does not know amphetamines are dangerous, mind altering, addictive drugs blows my mind. Although, they believe opioids are “safe pain killers” as well. When did the doctors become so stupid?

Report comment

Despite the evidence, over prescription of ________(Fill in the blank)

A. Stimulants

B. Neuroleptics

C. Antidepressants

D. Benzodiazepines

E. Opioids

F. All of the above

continues.

Report comment

Frank, no doubt. Another issue is that many “patients” still demand these drugs from their doctors, because they’ve been conditioned to believe that the pills will somehow fix how they feel.

Report comment

They have a lot of help from the drug industry with it’s advertising, and it’s lack of regulations. Do something about corruption in government, and you fix a lot of things.

Report comment

Frank, you are correct. Drug advertising should be outlawed, as it is manipulative and misleading. But Big Pharma, like all big business, is very influential over groups like the FDA, AMA, and Congress, so they get away with it. If we could take money and influence out of the equation, that would make such a difference. The other problem is that doctors themselves have set up an expectation from their patients that they will continue to get these pills indefinitely and have told their patients that these drugs are necessary for proper functioning. Many people who come to my clinic get angry at their doctors because they are limiting access to certain drugs like benzos and stimulants. Many clients see these pills as necessary to their functioning. Big Pharma is too influential over this whole mess.

Report comment

What do you think about the euphemistic use of the term “overprescription,” Frank? Wouldn’t it be more accurate to say “unneeded prescription” or “Unjustified drugging of children?” To me “overprescription” implies that there would be a ‘right’ level of prescription, which of course is impossible to determine when your criteria for diagnosis include such objective measures as “sometimes fails to wait his turn in line” or “sometimes acts as if ‘driven by a motor.'”

Report comment

Hi Steve. Maybe “misprescription” is the term you seek, as leapers not only don’t work, but also mask the existence of real sanity threatening sources of hyperactivity, such as lead poisoning.

Report comment

All drugging is over drugging. The problem is these doctors think that what they’ve got is some kind of medicine when they don’t, it’s just another drug. What’s more, although they may not say so, these are social control drugs, too. So if the problem isn’t really “sickness”, and it isn’t, it is behaviors that gets somebody’s disapproval. That’s the trickier part. Psychiatric treatment is based upon intolerance. Get a person not to tolerate his or her own behavior, and you’ve won the social control ball game.

Report comment

Don’t forget that some portion of children prescribed stimulants never take a single dose. Mummy-daddy needs a little pick-me-up now and then, so why not trot the kid over to the pharma-crazed prescribers who themselves are probably jacked to the gills as they scribble out new guidelines for diagnosing ADHD in adults “in whom the symptoms can be subtle. In fact, we’re finding that we were quite wrong to say adult-onset ADHD does not exist.” Most pediatricians are women in Canada, which might be why there are so many articles about the atypical symptoms, including none, of ADHD in adult women.

“it’s a condition that was traditionally thought to affect mostly males, but also because females tend to have a less obvious type than males…”

“Adults with ADHD may have difficulty following directions, remembering information, concentrating, organizing tasks, or completing work within …” or they might be on too many memory-impairing statins and brain-oxygen-depleting beta-blockers and halfway to chemical-caused dementia. (Refer to Dale Bredesen’s “The End of Alzheimer’s” for help with that.)

Report comment