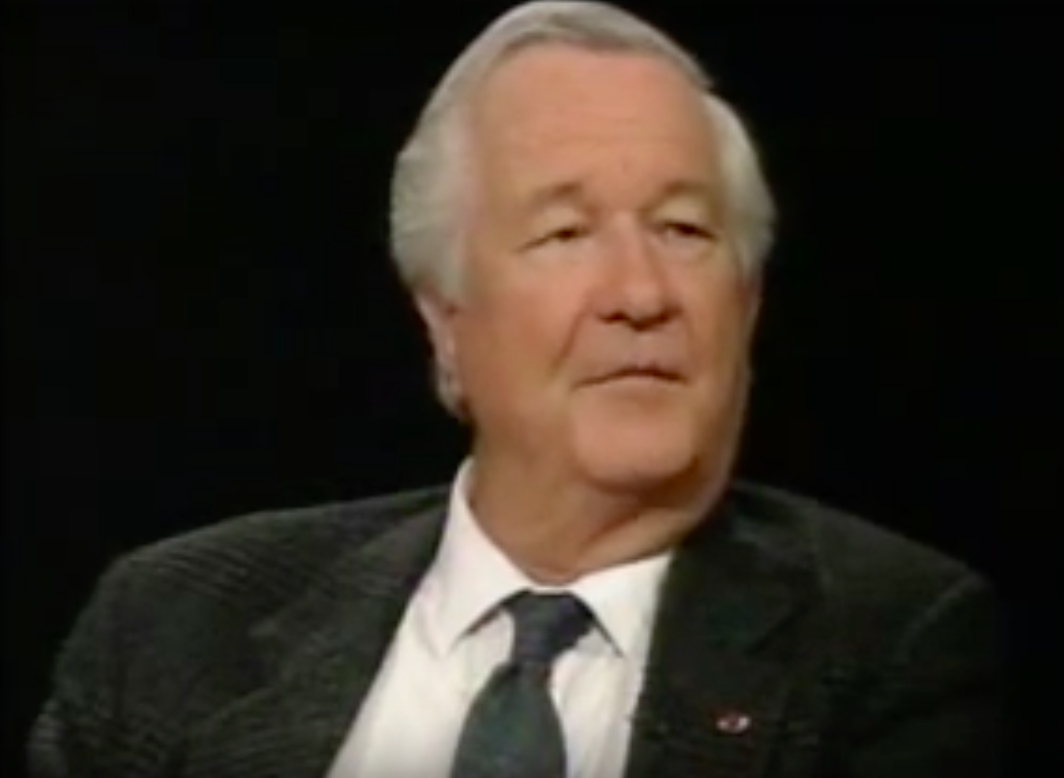

The year was 1991. The scene was a conference of public health officials in Washington, DC. America’s leading mental health advocate was in town to deliver the keynote address about depression, the subject of his recent New York Times-bestselling memoir. His talk stressing “the message of hope,” as he wrote a couple of years later, was well received.

But a curious thing happened immediately afterwards at the press conference in his honor attended by some thirty prominent medical journalists. The first questioner asked him to talk about the antidepressant du jour, Prozac, which had been released a few years earlier. The eloquent man gave a nuanced answer, saying that while he himself had never used the Lilly drug, he understood that there could be a few different reactions. For one group, he stated, there was evidence that it could be quite beneficial; for another, it had little or no effect; and for a significant few, “it produced sinister reactions, primarily suicidal fantasies.”

Much to the surprise of the eminence grise, soon after he finished this sentence, America’s top psychiatrist—the acting director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)—suddenly grabbed the microphone and proceeded to finish his answer, describing Prozac as “virtually free of the serious reactions that have plagued antidepressants in the past… a truly remarkable development in psychopharmacology.” Over the next fifteen minutes, all the succeeding questions were also answered not by the famous author, but by the NIMH director, who then declared the press conference over.

“As I wandered out,” the speaker later observed, “I felt so ludicrously discomfited that I barely heard the canny, sympathetic Deep South voice of one of the journalists: ‘Boy the guv’ment sure did shut you up, didn’t they?’”

Listening to Styron

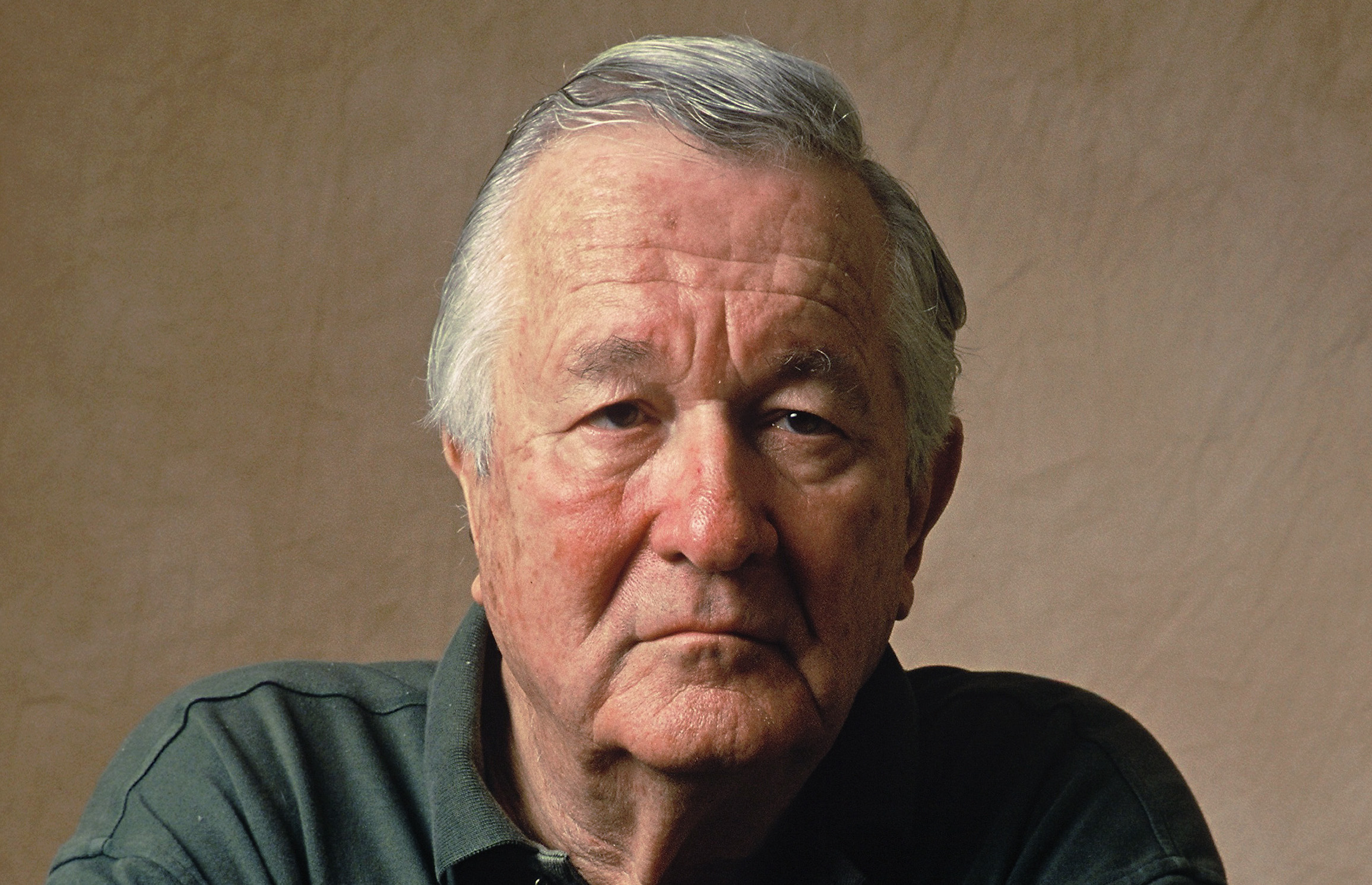

While many of us think we know exactly what William Styron, the acclaimed author of the National Book Award-winning novel Sophie’s Choice (1979), who died at 81 in 2006, had to say about depression and its treatment, to this day, his true voice has often been muffled, or even snuffed out. In fact, the reigning interpretation of his landmark work, Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness (1990), which was based on a talk that he gave at the Johns Hopkins Medical School thirty years ago this spring, is misleading.

Styron’s gut-wrenching 84-page text describing his battle with suicidal despair in the mid-1980s has long been read as an endorsement of the biological revolution in psychiatry, which swept the nation soon after the publication of DSM-III in 1980. This version of psychiatry’s diagnostic bible was the one that officially turned drug therapy—rather than talk therapy—into the treatment of choice for most psychiatric disorders.

Styron’s gut-wrenching 84-page text describing his battle with suicidal despair in the mid-1980s has long been read as an endorsement of the biological revolution in psychiatry, which swept the nation soon after the publication of DSM-III in 1980. This version of psychiatry’s diagnostic bible was the one that officially turned drug therapy—rather than talk therapy—into the treatment of choice for most psychiatric disorders.

In a New York Times op-ed published last summer upon the release of her podcast on Styron, “The Great God of Depression,” science journalist Pagan Kennedy gives the standard assessment: “Mr. Styron . . . helped to popularize a new way of looking at the brain. In his telling, suicidal depression is a physical ailment . . . The book includes a cursory discussion of the chemistry of the brain — neurotransmitters, serotonin and so forth. For many readers, it was a first introduction to scientific ideas that are now widely accepted.”

But a close look at Styron’s own words reveals that he was a persistent critic of these supposedly scientific ideas about how changing brain chemistry can cure depression and other psychiatric ills. In fact, in a 1990 New York Times interview right after the publication of his book, he said, “I think that the combination of a couple of drugs really augmented my despair. I believe their promiscuous use is very dangerous.”

There, in a nutshell, is the forbidden thought: that the drugs sometimes “augmented” his depression. That self-understanding has been lost from the conventional narrative that has reduced Darkness Visible into an easily digestible case study—for both consumers and medical professionals alike—providing proof that depression is a biological illness that is best treated by psychiatric drugs (or other biological treatments). But could Styron’s life story instead be a cautionary tale that warns us of some serious problems with contemporary psychiatric treatment—of how rather than addressing what really ails depressed patients, it may sometimes actually increase their despair?

To dig deeper into the meaning of Darkness Visible and to learn more about the circumstances of Styron’s life, I conducted interviews with his widow, Rose, two of this four children (Thomas, a clinical psychologist and Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Yale, and Alexandra, author of the 2011 memoir, Reading My Father), and a Harvard neurologist, Alice Flaherty, who treated—as she dubbed Styron—the “Great God of Depression.” Given Styron’s unwavering commitment to improving the lot of all patients suffering from depression, Flaherty—as well as surviving family members—believe that he would have wanted them to be open about the details of his treatment. (Flaherty and Rose Styron also spoke to Pagan Kennedy for her podcast.)

Styron’s First Round of Depression

There is a strong line of evidence, which I discovered through my reporting, that Styron’s various episodes of acute suicidality were typically not triggered by his underlying emotional distress, nor by any genetic biological illness, as the conventional wisdom would have it. Instead, it appears that his biological treatments often played a major role in the onset of the extreme emotional discomfort that almost led him to take his own life on numerous occasions.

In the fall of 1985, Styron struggled with constant thoughts of suicide, which he movingly depicts in Darkness Visible. Yet, eight years later, in a 1993 essay for The Nation titled “Prozac Days, Halcion Nights,” Styron asserted that this period of acute suicidal ideation was fueled by the use of the tranquilizer, Halcion, which he had been taking for insomnia: “Although the depression I describe in my book was not caused by Halcion . . . I’ve become convinced that the pill greatly exaggerated my disorder, intensified my suicidal feelings and finally forced me to be hospitalized.”

Halcion is a fast-acting benzodiazepine. As WebMD notes, known side effects include “worsening depression, abnormal thoughts, thoughts of suicide, hallucinations, confusion, agitation, aggressive behavior and anxiety.”

Indeed, Darkness Visible actually reveals how Styron was miraculously cured of his intense suicidal urges not by taking a pill, but by ceasing to take a pill.

When Styron’s narrative of depression begins, we find him in Paris in October of 1985. He has recently given up his lifelong drinking habit. He is feeling depressed and anxious and is having difficulty sleeping. But it was not until he started taking Halcion, a drug to which he soon became addicted, that he starts feeling acutely suicidal.

After his return from Paris, Styron begins seeing a psychiatrist, whom he names Dr. Gold, in order to “obtain help through pharmacology.” But neither of the two pills that Dr. Gold tries—the tricyclic antidepressant, Ludomil, nor the MAO inhibitor, Nardil—does much of anything, and so, in December, Styron decides to seek help at Yale-New Haven Hospital. Within a few hours of his admission, a staff psychiatrist is shocked to discover that Dr. Gold has been urging him to take three times the normally prescribed dose of Halcion. Styron is then switched immediately to another sleeping pill, the antihistamine Dalmane. “Soon after,” he later writes, “my suicidal notions dwindled then disappeared.”

In that 1993 Nation essay, Styron also expresses his fury at Upjohn’s “refusal to face up to the Frankenstein’s monster its Kalamazoo laboratories let loose in the shape of Halcion.” Noting that Halcion has been banned from a half dozen countries, including Britain and the Netherlands, Styron also saves some rage for the “ever-supine” FDA for “its cavalier decision” to allow this sleeping pill to be sold in the United States despite all the evidence implicating it in numerous suicides and acts of violence.

As Rose Styron recalls, her late husband’s first bout of depression resolved itself completely not long after his seven-week hospital stay ended. “Within several months, he was off all medication and he felt terrific. He was back to his old self,” she says. “And he was no longer seeing a psychiatrist, as he didn’t do talk therapy.”

His doctor Alice Flaherty concedes that drugs had little to do with Styron’s recovery from the depression chronicled in Darkness Visible. “Most episodes of depressions go away after eighteen months without intervention, and his depression probably just ran its natural course,” she says.

William Styron on his first depression: you can expect to recover

William Styron on his first depression: you can expect to recover

Second Descent into Darkness

However, after fourteen years, Styron’s depression came back with a vengeance. “In early 2000, we took a wonderful trip to Cuba, but he was never the same after that,” Rose says. From June until November that year, he was hospitalized on several occasions. However, the hospital stays proved far from therapeutic. “He came home to the Vineyard, ragged, out of his mind, patched together with psychopharmacological tape and thread. And then the shit really hit the fan,” writes his youngest child, Alexandra, in Reading My Father.

Once again, a drug had greatly exacerbated his initial distress. In a letter to a friend in early 2002, Styron explained the reason for his inpatient treatment in 2000: “It was a sudden major depression (induced, I’m certain, paradoxically by the malefic effect of an anti-depressant).” The offending antidepressant, Alexandra reports, was Wellbutrin.

Styron would remain a revolving door psychiatric inpatient until his death in November of 2006. He was repeatedly hospitalized at three different facilities—Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Martha’s Vineyard Hospital and at New York Presbyterian/Columbia University.

Alice Flaherty, whom I met with in her office at Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital this past February, said that she reviewed Styron’s entire psychiatric history before seeing him for the first time in January of 2004. She continued to monitor him closely for the last two years of his life. “Meds never really helped Styron,” she says. “All kinds of antidepressants were tried over the years, but they were used much more for show than effect. Cymbalta may have once reduced his pain a bit, but that was about it.”

Between August of 2003 and October of 2004, Styron was hospitalized about a half dozen times at MGH alone—with a couple of the stays lasting a few months. And the subsequent treatments that he tried both as an inpatient and as an outpatient—massive drug cocktails along with a few rounds of ECT—typically either had no effect or, even worse, intensified his suicidal despair. He had fallen into a pit of unending darkness.

His Psychiatrist’s Perspective

Flaherty, who is an adherent of a strict biological approach in treating her patients with psychiatric conditions, said that Styron “was really sick and like about 30% of patients with depression, he was treatment-resistant. Today I might address his suicidality with ketamine.”

As opposed to Dr. Gold and a few other biological psychiatrists who treated Styron, Flaherty followed treatment guidelines carefully. Flaherty also developed a close bond with both Styron and his wife—she was a regular visitor to their home in Martha’s Vineyard—and she clearly had her patient’s best interests at heart. “By the time I saw him, many senior psychiatrists wanted to get rid of him. They saw him as a difficult patient who was a pain. I was female and low-status at the time,” she says.

Doctor and patient also connected over writing. Flaherty had just published her own memoir, The Midnight Disease: The Drive to Write, Writer’s Block and the Creative Brain (2004), about her long bout with hypergraphia—the inability to stop writing. And one of the things that was driving Styron crazy was the flip side of her condition—hypographia—as he had not written a major novel in over 20 years.

Flaherty was doing her job conscientiously—practicing psychiatry as it is supposed to be practiced in 21st century America. But in hindsight, other explanations for this repeated treatment failure are evident. Rather than conclude that Styron was “resistant to medication” and ECT, perhaps the problem was that drugs and ECT were not likely to be an effective remedy for what ailed Styron.

The Childhood Traumas That Shaped Both His Life and Work

While the severity of Styron’s first breakdown can be traced back to iatrogenic complications—a toxic medication prescribed at unconscionably high levels by Dr. Gold—Styron understood that its underlying cause had to do with emotional problems that he had struggled with since childhood. “In my case Halcion was not an independent villain,” he writes in Darkness Visible, “I was headed for the abyss—but I believe that without it I might not have been brought so low.”

Throughout his life, as surviving family members attest, Styron suffered from chronic anxiety and irritability. Thomas believes that this constant distress led him to be very self-absorbed. He recalls that his father had little emotional room for him and his three siblings when they were growing up.

“He was not interested in me for the most part,” says Thomas. “Worse, he often had temper tantrums directed at us [the children] or at my mother. He was very reactive and had a hard time processing any feelings.”

In a letter written during her father’s first depression, Alexandra similarly told him that while she loved him, he had often been “a grouch and an ogre.”

Rose believes that many of his persistent fears were directly related to the chaotic circumstances of his childhood. “If I was a half hour late coming back from ice-skating, he would be standing at the door. He was constantly worried about my safety and the safety of the children. He feared a bad end for us. That probably was tied to the catastrophe of his mother’s death, which as a boy, he always knew was coming soon.”

As documented by biographer James L. W. West in William Styron: A Life (1998), when Bill was just two, his mother, Pauline, found a lump on her breast; shortly thereafter, she had a double mastectomy. While her only child did not know about her illness until nearly a decade later, she was often frail. And the last couple of years of her life—she died when Styron was thirteen—were grueling. Pauline’s hair fell out, and she was largely confined to her bed. Parent-child roles were reversed, as her son was often expected to take care of her.

Unfortunately, Styron could not count on his father, William Sr., for steady nurturing. While William Sr. had a calm exterior and could be loving—he would later emerge as a critical source of emotional and financial support as Bill embarked on his career as a novelist—he harbored an explosive anger within that could suddenly pop out of nowhere. As a middle-aged man, William Sr. once got into a fist-fight with a co-worker that resulted in such a severe injury to his shoulder that for months he had to strap up his entire upper body upon waking every morning.

The emotional and financial toll of Pauline’s illness left William Sr. unhinged for years. One day about a year after his mother died, Styron was in his bedroom when he heard a disturbing clang. Rushing downstairs, he saw that his father had smashed the family’s plastic radio. A few weeks later, his father checked himself into a hospital for three weeks.

That was essentially the end of Styron’s childhood. His frazzled father soon shipped Bill off to prep school before getting hitched to a second wife, Elizabeth. Styron then felt as if he no longer had a home, and he wanted nothing more to do with his native Newport News, VA. His stepmother Elizabeth was obsessed with neatness and controlling others, and she often criticized her adolescent stepson, never treating him with much kindness or respect.

In the early 1950s, soon after Styron first proposed to Rose, Elizabeth took it upon herself to write his fiancée, then in Italy, a warning letter, exhorting her not to marry her wayward stepson. “I was horrified and never showed Bill the letter,” Rose says.

Shortly after he left Yale-New Haven Hospital in early 1986, Styron completed a short story, “A Tidewater Morning,” which pivots around the harrowing death of the mother of his thirteen year-old alter ego, Paul Whitehurst. After she breathes her last breath, Styron finishes the story with these lines:

“We each devise our means of escape from the intolerable. Sometimes we fantasize it out of existence . . . I let myself be elevated slowly up and up through the room’s hot, dense shadows. And there… I was able to gaze down impassively on the grieving father and the boy pinioned in his arms.”

For Styron, this traumatic scene, which Alexandra calls “the seminal event of his life,” was an out-of-body experience that would have reverberations for decades. As West notes, he was numb at the time and never really grieved the loss of his mother.

In his previous fiction, Styron had written about his own feelings of sadness and suicidality through the experiences of his characters—most notably, through Sophie Zawistowski, the Holocaust survivor immortalized by Meryl Streep in her Oscar-winning role. But this was the first time that he had directly addressed his own inner torment.

Styron’s daughter, Alexandra, believes that this was a major breakthrough for him, as he was beginning to see the roots of “the intolerable” feelings associated with his first depression in his own history. “In this thinly veiled piece, his psychological defenses were broken down profoundly for the first time,” she says. “My father was never able to talk about his feelings. But somehow he could dig deep in his fiction. On the page, he could achieve emotional depth—but not in real life.”

For a time, this new sense of inner connectedness appeared to serve Styron well. According to Thomas, his father was a different person from the late 1980s until 2000. “It wasn’t that we were suddenly going on camping trips together, but my visits home were quite pleasant. We began having a great time in each other’s company.”

The Despair of Writer’s Block

While it’s impossible to know exactly what caused Styron’s second breakdown in 2000, the primary culprit mentioned by family members was his lack of progress on a new novel. As his eldest daughter, Susanna, noted in a diary entry that spring, “Then he [Styron] said the most interesting thing: the worst thing about him is that he’d been unproductive and fallow. He hadn’t written a novel in 20 years, hadn’t done the work he was supposed to do. I realized how painful that was for him.”

In the early part of his writing career, Styron had written at least one major novel every decade, and yet, by 2000, he had published no fiction except for a few short stories since Sophie’s Choice, which appeared in 1979. Styron’s papers at Duke contain countless manuscript pages of a novel about his experience in the Marines during World War II. In the summer of 1945, Styron was finishing up officer training, but the war ended before he saw any combat duty. Despite numerous attempts, Styron never managed to organize a coherent narrative. “He didn’t have the confidence to write big novels anymore. He felt that whatever he wrote was not good enough,” says Alexandra.

Alexandra Styron on her father’s writer’s block and life

In early 2000, with his confidence in his writing at a low, Styron’s feelings of worthlessness and anxiety led him to go back on medication. But when he grew even more depressed while on Wellbutrin, he became desperate.

“There was a meta-aspect to his second depression,” says Alexandra. “He felt the hoofbeat of depression and he was horrified. He wanted a quick fix.”

The quick fix that Styron settled on was ECT. “One of the reasons that he wanted to try ECT was that he had had such a bad experience with drugs, and he didn’t want to take another one,” Rose says. “I researched ECT and told him about the minuses, but he insisted.”

Styron started ECT on an outpatient basis, but when he developed a serious side effect—urinary retention—he entered Yale New Haven Hospital, where he received thrice-weekly shock treatments. After a short time, he refused to get the treatments anymore. Once when Rose accompanied him to an ECT treatment, he yelled at her, “You’re killing me!”

“That was tough to hear,” she says. The ECT was then abandoned, but not before possibly causing the Parkinsonian symptoms that emerged that summer, as Alexandra notes in her memoir.

In August of 2000, a heavily medicated Styron returned to the family’s home on Martha’s Vineyard. According to Rose, for the next couple of years, he was treated by a Doctor of General Medicine on the Vineyard, who prescribed various drug cocktails. “This doctor failed Bill,” she says. “He took way too much medication for too long.”

When he continued to struggle, Rose tried to place him at Martha’s Vineyard Hospital, which then did not have a unit specifically for psychiatric patients. “The admitting doctor traumatized Bill,” says Rose. “He blurted out, ‘We don’t take mental patients!’”

That’s how Styron ended up going to MGH where he was followed up on by Flaherty during his inpatient stays. “On his first visit to MGH, he remained catatonic for several weeks, as the rude treatment by the admitting doctor in Martha’s Vineyard had a profound effect on him,” Rose adds.

His Son Finds a Different Path

A few years after Styron recovered from his first breakdown, his son, Thomas, then about 30, fell into a deep depression of his own. He was between college and graduate school. “I was working for a non-profit that helped the homeless, and I was busy trying to save lots of souls. In the end, what really helped me was lots of psychotherapy and time,” he says.

Thomas notes that at the end of Darkness Visible, his father preached that patience was a very important factor in recovery from depression. “The truth [is],” concludes Styron, in his memoir, “that depression is not the soul’s annihilation; men and women who have recovered from the disease—and they are countless—bear witness to its only saving grace: it is conquerable.”

“But he himself had a hard time practicing that,” Thomas says. “My dad wanted the pain to end right away, and that’s when he opted for aggressive interventions like a new medication or ECT, which often made his condition worse.”

And given the prevailing “biological” thinking, there was no shortage of physicians willing to help Styron get a quick fix for his depression. That’s what the treatment guidelines for suicidal depression then advocated, and they still do today.

In her book, Night Falls Fast: Understanding Suicide (1999), Johns Hopkins University psychologist Kay Jamison—who first met Styron at his 1989 Hopkins talk and provided clinical advice to him during his second depression—recommends “specialized and aggressive use of medications” to treat suicidal urges, which, as per her biological perspective, she attributes to “genetic vulnerabilities, severe psychiatric illness and acute psychological stress.”

Nowhere in Jamison’s bestselling book is there any mention of how childhood trauma—say, sexual abuse or the chaotic family circumstances experienced by Styron—can play a role in the onset of deep despair decades later.

Thomas Styron is convinced of the wisdom of the advice given by his father—the father that was the sensitive writer, and not, to use the phrase of his sister Alexandra, “the “emotionally unevolved human being.” Accepting that there is no quick fix made a big difference in Thomas’s life—he has been free of depression ever since—and he has seen it validated numerous times in his clinical work over the past twenty-five years. “There is good empirical evidence that if you are patient enough, depression will lift on its own. If you let the pain in, it often just runs its course.”

A Clash of Narratives

The promoters and defenders of the conventional narrative, which is that depression is a biological illness, manage to stuff Styron’s struggles with depression into a “biological” box. While it is sometimes acknowledged—even in that conventional narrative—that antidepressants and other somatic treatments ultimately failed to help him, the conventional narrative still has a place for Styron: he was “treatment resistant.”

It’s not that the dominant paradigm of care has any flaws that might require further examination; it’s simply that it can’t be expected to help everyone from depression, which is essentially a mysterious illness.

But as can be seen in this re-examination of his life, William Styron had a difficult childhood, and he understood that his descent into the depths of depression, following the triumph of his novel Sophie’s Choice, was related to the deep emotional pain that he had lived with for decades. And his first bout of depression, as Styron realized, was then exacerbated by a psychiatric drug, Halcion; fortunately, after stopping Halcion during a 7-week hospital stay in which he did some soul searching, his depression quickly improved. However, 14 years later, when a new episode visited him, a despair apparently triggered by his writing difficulties, he entered into a world of one course of aggressive somatic psychiatric treatment after another, and never again came out of his despair.

That’s a different life story, one that, it might be said, provides a powerful warning about how our biological paradigm of care may sometimes not be at all helpful—or may even be harmful—to patients suffering from depression.

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

Gee, ain’t it funny how ODD…No, not that ODD! I mean Obsessive Depressive Disorder, once cannibalizing the life of a single individual can then leap to other members of his immediate circle and send many family members and associates careering, perpetually, into the eerie half-light of The Mental Health Zone.

Report comment

This is a (psychiatric) disgrace. I suspect I could do a better job than that, using nutrients off his pharmacies’ shelves, than his doctors did with their access to all the stores’ prescriptions.

Report comment

I bet you listen to those you try to help too.

If one said, “Hey, since trying this herb you recommended I can’t sleep and feel nervous all the time,” you wouldn’t double the dosage. (Then forcibly inject it when he/she demurs.)

Report comment

Childhood with angry disinterested parent(s) would have a lot to do with depression. Happened to my mother, and me also, except mine were emotionally dead as well as disinterested. I think the mind makes a lot of parts, each one almost a person in itself (IFS model), and they are all doing their thing, which explains the chaotic nature of feelings in life. The mind is complicated. If you knew all the parts and what each one was up to, it would make sense.

Report comment

But could Styron’s life story instead be a cautionary tale that warns us of some serious problems with contemporary psychiatric treatment

I think hardly, unless one already pretty much knows the deal about psychiatry. I think his book likely sent many people down the primrose path to hell, and I think Abbie Hoffman might have been one of them. I believe Styron was sitting in front of me at Abbie’s memorial, and I remember his talk striking me as egotistical and self-absorbed.

[Just googled this. Styron knew Abbie & testified at the Chicago 7 trial, and wrote about Abbie’s suicide in his book, published later in 1989.]

Report comment

If anyone here wants to know anything about human psyche. …

I am not able to say everything in just one post, I can only leave the correct address. Wisdom is everything, and psychiatry is just a nowadays form of inquisition.

Do not forget that psychiatry has no connections with wisdom and the original nature of the psyche. Death has,human psyche has, but authoritarians are far away from it. I have in my ass everything which they have to say about psyche. They are using the wrong language. Well, psyche odes not exists for them. Corrupt murderers traitors and liars. Crazy apollonians.

“Re- Visioning psychology”. James Hillman

I have also a song for psychiatrists RESISTANT to wisdom.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VJuXKeiM4_0

Heil Psyche. By bye psychiatry.

You are using the wrong language, and false empiricism for describing psychological reality. And you have no idea what psyche is.

Report comment

another good story is in THE NEW YORKER

APRIL 8TH—–THE BITTER PILL…why do we know

so little about how to stop taking psychiatry drugs…

Report comment

It’s business. There’s no steadier drug customer than an addict- someone who can’t stop using and will do anything to get his/her fix, including robbing banks, and even their grandmothers, to get the money to score. This is one reason dealers frequently have home arsenals.

Report comment

Trying to treat depression by altering the brain chemistry…isn’t that what alcoholics already do? The big difference between an alcoholic and a “meds compliant consumer” is one regularly visits the bartender. The other sees a guy who claims the soul is an organ and the drugs he pushes will save it.

If a bartender were found to be kidnapping former customers and forcing them to drink copious amounts of Scotch or whiskey he would get in big trouble. And he can’t bill Medicaid for the booze.

Report comment

Rachel: Your point is well taken.

Paris Review recently posted an early interview with Styron:

https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/5114/william-styron-the-art-of-fiction-no-5-william-styron

Here’s what he said about his working method when he was 28:

I like to stay up late at night and get drunk and sleep late. I wish I could break the habit but I can’t. The afternoon is the only time I have left and I try to use it to the best advantage, with a hangover.

So before his crisis in the 1980s, he was no doubt drinking a lot to deal with his chronic anxiety. To go from bartenders to psychiatrists was a natural move for him.

Report comment

Curiously, Andrew Solomon’s first episode of “agitated depression” was also misdiagnosed benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. Coming from a family fortune from the pharmaceutical industry, he was convinced that he needed serious psychiatric drug treatment. He went through years of antidepressant switches and more adverse reactions — no doubt also misdiagnosed as psychiatric symptoms — and now claims to be in a drug-balanced state.

He’s been preaching about the need to treat depression and the effectiveness of antidepressants ever since. Of course, he did delve into his history and found good reason for psychiatric disorder — very few among us do not have this!

His journey into psychiatric drugs is recounted in an article he wrote for the January 4, 1998 New Yorker, Anatomy of Melancholy https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1998/01/12/anatomy-of-melancholy

David Foster Wallace experienced years of misdiagnosed Nardil withdrawal syndrome. He experienced round after round of additional psychiatric drugs. He was convinced the drugs were making him worse. Did he kill himself because he thought he had an incurable psychiatric condition?

These circumstances are contained in a February 28, 2009 New Yorker piece by D.T. Max https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/03/09/the-unfinished

“….In the late eighties, doctors had prescribed Nardil for Wallace’s depression. Nardil, an antidepressant developed in the late fifties, is a monoamine oxidase inhibitor that is rarely given for long periods of time, because of its side effects, which include low blood pressure and bloating. Nardil can also interact badly with many foods. One day in the spring of 2007, when Wallace was feeling stymied by the Long Thing, he ate at a Persian restaurant in Claremont, and afterward he went home ill. A doctor thought that Nardil might be responsible. For some time, Wallace had come to suspect that the drug was also interfering with his creative evolution. He worried that it muted his emotions, blocking the leap he was trying to make as a writer. He thought that removing the scrim of Nardil might help him see a way out of his creative impasse. Of course, as he recognized even then, maybe the drug wasn’t the problem; maybe he simply was distant, or maybe boredom was too hard a subject. He wondered if the novel was the right medium for what he was trying to say, and worried that he had lost the passion necessary to complete it.

That summer, Wallace went off the antidepressant. He hoped to be as drug free as Don Gately, and as calm. Wallace would finish the Long Thing with a clean brain. He entered this new period of life with what Franzen calls “a sense of optimism and a sense of terrible fear.”….”

D.T. Max later published a biography about Wallace with more detail.

After going off Nardil, Wallace embarked on the kind of hell anyone who has experienced antidepressant withdrawal syndrome will recognize, replete with misdiagnosis, denial, and hypersensitivity to subsequent psychiatric drugs. Since he had a long psychiatric history and prior suicide attempts, his suicide is attributed to his pre-existing mental condition.

In my experience, after reading thousands of reports from patients and collecting more than 6,000 longitudinal case histories of psychiatric drug tapering and withdrawal symptoms on my Web site Surviving Antidepressants http://survivingantidepressants.org/index.php?/forum/3-introductions-and-updates/ , physicians, including psychiatrists, generally do not recognize any psychiatric drug adverse effects and almost invariably misdiagnose withdrawal as relapse or emergence of a new, weird psychiatric disorder calling for high dosages of lots of drugs, which tend to make people worse.

Clearly, there is a longstanding area of physician error in misdiagnosis of psychiatric drug adverse reactions and withdrawal symptoms and consequent patient harm. My belief is they think such adverse reactions are so rare, they’d never see them in their patients. They presume everything is a horse, not a zebra. Too bad we’re losing so many zebras.

Report comment

There is something to be said about the fact that antidepressants and tranquilizers just do not mix well together when prescribed to the same patient. Surely, it seems like such a good idea at first. Prescribe an anti-depressant such as an SSRI as a 1st line of pharmaceutical treatment and then prescribe some sot of a benzodiazepine tranquilizer for bad anxiety/panic attacks/insomnia/nightmares. Sounds like a winner, right?

Sadly, benzodiazepines can worsen pre-existing depression, as Styron correctly noted. Having read Darkness Visible in its entirety, I do recall that the first tranquilizer Styron was prescribed was Ativan, not Halcion. Somewhere along the lines, Styron receives a change from an already short-to-intermediate acting Ativan to an even shorter acting Halcion that can be even more problematic than Ativan. The author of this article correctly notes that Dalmane was given to Styron at the hospital to stop Halcion, but Dalmane is also a benzodiazepine tranquilizer, and not an antihistamine, as the author suggests. As cold turkey from any long term benzo use is not recommended under any circumstances, it makes sense that Styron was given a much longer lasting Dalmane in place of the short-acting Halcion, which has such a ridiculously short half-life that it may be impossible to taper off of directly. It’s no wonder Styron was so angry at the FDA about allowing this particular drug.

But going back to my original theme, I have myself exeprienced much agitated depression from benzodiazepine tolerance and withdrawal syndrome, and it is actually that this syndrome, when severe enough, will make a patient generally unable to tolerate an antidepressant that might have been tolerated prior to commencing the use of benzodiazepine. Now, if a psychiatrist insists on a patient taking the antidepressant, then the patient faces a dilemma of either a) not taking the antidepressant at all and pretending that they do, b) taking it in much smaller dosages, as the ability to tolerate it is further reduced, or c) allowing the doctor to add another CNS depressant type medication to be able to tolerate the anti-depressant or d) increase the dose of the prescribed benzo to counter the antidepressant’s side effects, risking even more problems with benzodiazepines and even more central nervous system instability, which may in the end cause the patient to be labeled “treatment-resistant”.

Nowadays, whenever I see the words “treatment resistant”, I always can’t help but wonder if benzodiazepine is/was a part of their medication regimen.

Report comment

The so-called “antidepressants” do not work any better than placebo. This is proven. So they are useless and are many times dangerous, often inducing the very thing that they’re supposed to protect people from, wanting to take their own lives or the lives of others. “Treatment resistant” is just psychiatry’s response when their so-called treatment proves to be totally useless. People should stay away from benzos and “antidepressants”.

Report comment

They did effect me. The SSRI known as Anafranil kept me awake for 3 weeks in a row. Brought on psychotic mania–for which Dr. M blamed me.

#patientshaming is my rebuttal to #pillshaming. The latter hash tag is just the psych establishment’s attempt to cover its naked rump with a kleenex. Not hard to see through.

Report comment

I have read all those books, most of them while I was in graduate school. I recall what Styron said of Dr. Gold, that he liked the man well enough, but that the doctor had failed to help him.

I remember Andrew Solomon’s head trip with “agitated depression” which was clearly drug-induced. He does say so.

As for inability to write, that’s about the worst thing that can happen to a writer. Or…being told you aren’t allowed to write and threatened with drugs if you do. I remember when I went into the nuthouses, I asked for a pencil and paper and that was all I needed to feel okay.

To work through trauma from hospital abuse I wrote in my blog, told the story over and over until I was done with it. Writing is not only a comfort for me, but it is a means for activism and communication. I believe the one thing I want to do more than anything is to tell my story so that others will be forewarned, and also to bring hope to people. Yes, there is life after psychiatry.

Report comment

This is fascinating and very sad to read.

Report comment

Thank you for taking the microphone back from NIMH and handing it to Styron and the people who most knew and loved him. This is a beautifully written and important story.

Report comment