Before I went off to college, my mom gave me some advice: Smile. Be nice to everyone you meet and you will have no problem fitting in. Desperate to make up for my lack of friends, I took her advice too literally and walked around campus with a constant smile on my face. Not a full smile, but a vague, remembering-something-funny smile—the sort of expression I hoped might portray the openness my mom was referring to without crossing the line to lunacy.

By sophomore year, after many failed attempts to make friends, I decided to get a job at a nearby coffee shop. Within the first week, I became close with a girl named Harley. She and I had a lot in common, from binge-eating problems to anti-social tendencies, but my absolute favorite quality of hers was her honesty. She could say anything to anyone and get away with it because her observations were always hilarious, until the day she turned around and started observing me:

“Hey, did you know you walk by my class every Tuesday?”

I shook my head.

“Yeah, and you’re always smiling. It’s really strange.”

Really strange. After a year and a half of upholding what I thought was a friendly demeanor, all I had managed to do was come across as really strange. I went home that night and promised myself never to take my mom’s advice again.

A couple of years after I graduated and moved back home with my parents, I decided to go for a walk. I kept my gaze down and my expression flat—a look I knew well from high school. People weren’t drawn to me when I acted this way, but they weren’t invited to make fun of me either. Appearing closed-off instead of strange seemed like the better option, that is until I walked by a neighbor who noticed my gloomy appearance and felt inspired to say:

“Smile! It gets better.”

When I looked up, he had a big grin on his face, as if he was trying to visually teach me how to smile. His intentions were good, but in the moment, his words felt cruel. I was twenty-one years old, lonely, depressed, and unbelievably insecure. The last thing I wanted was a stranger telling me to smile when I could hardly think of a reason to fake one myself. I walked away feeling more confused about my appearance than before.

A few months later, deep in the trenches of depression, I stopped caring what people thought of me. I stopped thinking about Harley and my mom. I stopped thinking about the girl in high school who told me I giggle too much and the bartender who asked why I looked so happy in my license picture and the professor who told me I never smile. I stopped trying to figure out whose perception was the truth. These questions didn’t matter anymore. All my insecurities just sort of drifted away as I fell into a pill-induced sleep, too weak from the muscle relaxers I’d taken to make any conscious facial expression at all. Suicide had begun to feel like my answer.

The next morning, I was rushed to the emergency room and transferred to the psychiatric floor. As the nurses walked me in, my first instinct under the heat of all the other patients’ eyes was to smile. Happiness was the last emotion I was feeling, but in the face of strangers, I reverted back to my mom’s advice. As the nurses disappeared and left me standing there, a large forty-something-year-old man emerged from the crowd.

“Let me guess: You took some pills thinking you were cool, is that it?”

Immediately, my nervous smile drained. His face changed, too.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to offend you.”

By this point, I was so broken down, so rejected by every facet of my life that I could no longer hide how I was feeling. The wall covering my true emotions had crumbled and now, for once in my life, I didn’t care if strangers could see them. That first day in the hospital was my first day as an adult where I actually looked the way I was feeling.

Joey never went to group meetings. He hardly ever came out of his room. I only knew his name because of our morning check-ins, where attendance was mandatory. We all had to sit in a circle and go around the room stating who we were and what we hoped to accomplish that day. I came up with a new goal every morning, hoping to impress the nurses with my enthusiasm and convince them to let me go home. Each time it was my turn to speak, the nurses lit up. They thought I was proof that their in-patient program worked, but really I was a big phony. By my third day in the hospital, I had gone back to my old vacantly smiling ways, except now instead of smiling to fit in, I was smiling to get out.

I both admired and pitied Joey because he was not a phony. He said the same thing every day: “I want to work on feeling happier.”

I wanted to clue him in—let him know he had to change his answer if he ever wanted to go home. The nurses would never let a depressed kid like him leave until he showed some kind of improvement.

By day six, I couldn’t take it anymore. I invited Joey to go with me to the evening AA meeting. These meetings happened every night at 8 p.m. and were open to everyone. A guest speaker would arrive and help pass the hour between dinner and bedtime as we all sat around a big table to listen. Some of the patients offered their own stories, but most of us remained silent. Participation was passive. I knew Joey would blend in well.

“But I don’t have a drinking problem,” he said.

“Neither do I, but anyone can go. All you have to do is listen. The stories can actually be pretty interesting.”

“Interesting” sounded less disrespectful in my mind, but I knew Joey would know what I meant. Just about anything was more interesting than staring at the clock, which took up the majority of the hospital days.

Joey agreed to come. During our supervised trip down to the first floor, he walked beside me. I had a hard time making conversation with Joey and I’m not exactly sure why. He stared at me while I spoke, which made me uncomfortable. Usually, I can read faces, but Joey’s was too full of thoughts. He spoke slowly, but I knew that inside, his mind was heavy with words. By the way his pimples swelled on his face and the homemade, candy necklace hugged his neck, I could tell Joey had seen more of this world than most people our age. He had experienced the cruelty too.

I wanted to hold his hand, but I knew that would be inappropriate. As “mentally ill” patients, we were supposed to maintain a level of disconnect from each other, as if we were contagious. We were miserable and lonely, but we had to mask these feelings. Hidden in corners, away from the nurses, we would confide in each other and talk about our lives outside the hospital. Whenever the clipboards and pens discovered us, we would go back to pretending. We would talk about how much better we were feeling and how positive our outlooks on life had become. Lying was necessary. Those nurses and their clipboards held all the power.

Once inside the meeting room, Joey sat next to me. I waved “hi” to several of the other patients as they entered and flocked around. Inside the hospital, I was a social butterfly and knew practically everyone on my wing, but at home, I was a nobody and a loner. I never knew I could be such a con artist. If only I had the energy to fake it one hundred percent of the time, then nobody would suspect a thing. Joey didn’t wave “hi.” He had no social skills to fake, so I kept him close. I empathized with him because he was the true me, emotionally naked.

Ten minutes into the meeting, Joey got up and walked toward the door. I thought he was going to the bathroom and forgot to ask a nurse to escort him, but when I caught a glimpse of his wide eyes, I realized something was wrong. One of the nurses rushed over in her trying-to-appear-calm, speed-walking way. She put her arm around him, but her embrace didn’t touch him. Her comfort hovered stiff an inch or two away from his trembling body. She escorted him out of the room and back up the elevator to the third floor. I wanted to follow, but for the sake of my own progress, I knew I couldn’t. I had to retain my healthy, happy, and ready-to-go-home guise. I had to remain still.

When the meeting was over, I found Joey sitting behind a wall in the bedroom quarters. He seemed more or less content, stringing together another candy-beaded necklace. I sat next to him but didn’t say a word. I knew questioning him wouldn’t help—prying made us all feel small. I hoped my company would be enough.

“My father is an alcoholic,” he said.

He was looking at me now, his half-finished necklace resting on his lap. I didn’t know what to say, so I didn’t say anything.

Joey went on, “He strangled me once. Like this.” He wrapped his hands around his neck. “He told me he wished I was dead.”

I swallowed, my throat suddenly dry. I tried to form a response.

“Jesus. That’s terrible. Do you still live with your dad?”

“Yes.” He looked down. “After this, I have to go back home to him.”

I breathed in deep. Now I knew why Joey didn’t bother to fake. He had no reason to. No matter where he was—in the hospital or at home—the world around him didn’t care. The nurses wanted to fix his brain, but they were only numbing the damage done by his father. Back home, the cycle for Joey would start all over again. I, on the other hand, had a family who cared. Even though I was mad at them for abandoning me and for hurting me when I was young, at least I had a reason to try and get out of this place.

As I thought over these things, Joey stared as he often did, thinking a hundred things at once but not saying a word. Despite the rules and the possibility of a setback, I moved in close and hugged him hard. He didn’t like others invading his space, but with me, he hugged back. I held him longer than I think I’ve ever held anyone. We both needed it.

“You have a lot of positive energy,” he said. “I feel safe when I’m around you, like I could tell you anything.”

I wished Joey’s words were true, but I think he was picking up on my phony façade. Still, it was one of the nicest things anyone has ever said to me.

Boxing is a process and a cycle, and delicious cutlets is the thing that are never too much.

Report comment

How much role play goes on in the wards? People pretending to be ‘medical’ people, others pretending to be patients who are either getting better or not depending on which direction they wish to take with this system of abuse.

I think you might enjoy this book by Yukio Mishima, Confessions of a Mask. I read it many years ago now. It must have been 15 BCD (Before my Civil Death).

Good to know some people get knocked down and get back up within this system, because when I got told I would be fuking destroyed for complaining about being kidnapped and tortured (yes I can prove it) they literally smashed my life to pieces. It did mean that others were harmed but the government has ways of ensuring the public doesn’t see their mistakes. Maybe they’re just knocking you down to toughen you up for the real world, and with me they wanted me dead because of speaking the truth? I don’t really know anymore, and to be honest care even less after 9 years of not seeing my family or being allowed access to even my personal belongings because of a government cover up. And I am now certain my community doesn’t care either, they no longer look at the ‘mask’, just turn to the wall for the Dead Man Walking.

I thank you all.

They prefer the narrative of the fraudulent documents sent to the Mental Health Law Centre to the Truth, the one where I was a mental patient and could lawfully be tortured and kidnapped. And consider how flimsy that protection from torture is, simply a matter of legal status that can be changed via fraudulent documents distributed by a Clinical Director (who I might add can afford to smile being paid $300K plus for committing serious offences against the community, though considered to be in their “best interest”). Exposing the ‘mechanism’ of psychiatry to the public of course would mean they may no longer consent to treatment (hey wait, they don’t) and well, that would require extra ordinary powers to ensure they public could be treated.

Torturing and brain damaging citizens is not a medical procedure, it is human and civil rights abuses. Confronting these delusional doctors with the truth is going to be a dangerous thing to do, the psychotic can react very badly to being confronted directly with the truth. Perhaps this is why the medical fraternity is allowing these people to think they’re doctors, so they can break it to them slowly that they’re not?

Report comment

Agreed.

Report comment

I think there’s something to be said for having a smile on your face. I find that people tend to smile back, if you have a mild smile on your face … which is nice. And you have such a pretty smile, your eyes even seemingly smile.

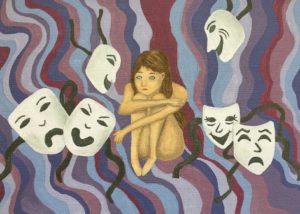

I think Joey’s comment was sincere, but I understand your distrust of it, based upon your painting. Keep trying to trust in the good within humanity. I do believe we are in the midst of a battle of good and evil, and do believe good will win over evil. Please pray good wins over evil.

Report comment

That’s great. Thank you so much.

Report comment

What’s your point?

Report comment

Great story. Thanks for sharing that with us. Could it be a chapter in a more lengthy book? I would encourage you to keep writing (and smiling). Smiling is like sunshine, ocasionnally it’s “too hot” but on most days, it is welcomed. In passing, I spend 4 to 5 days a week, every week, in hospitals, for: immunotherapy, chemotherapy and dialysis. Everyone has their nose in their phones: from doctors, nurses to other workers. In the hallways, elevators, and rooms.

We patients still smile amongst ourselves and so do the volonteers. The world has changed.

Report comment

Funny how no one talks about “sadness shaming.” Why do we need to go around grinning like the Cheshire Cat all the time for crying out loud?

And the “depression is a disease” is no help. It’s just a ploy to obligate you to take the “meds” and pretend they make you happy even when they make smiling nonstop more difficult than ever and you feel too numb to enjoy anything. And the original problem making you depressed is as bad or worse than ever.

People will quit yelling at you for being unhappy if you tell them you’re taking psychiatric drugs. That’s the only benefit I experienced long term.

One of the early Simpsons episodes showed Lisa going through the blues. In the end she pulls out of her funk when her mother, Marge, tells her the family will be there for her no matter how she feels and she doesn’t have to fake a smile anymore. Lisa smiles and tells her mom that this time it’s real.

Maybe once we quit treating the blues like leprosy fewer people will be depressed?

Report comment

It is horrible when there is no where to go home.

Report comment

If Joey had a woman like Melissa in his real life, he’d be cured within a month.

Report comment

Melissa this piece is both heart-warming and heart breaking. I commend you for your kind spirit in reaching out to Joey and others even though you struggle yourself. Being kind and supportive to each other is at the heart of promoting human welfare. The facade of psychiatry is that people in need of support or compassion realize it’s better to cover up their real feelings or what happened to them because psychiatry will only use it against them. This so-called “help” from psychiatric services could not be more deceitful and pathetic. When families are the reason behind a person’s trauma it’s even worse and I feel very badly for Joey having no safe place to go.

Report comment

Thank you angelic one for your love and kindness unlike most here you have no agenda other than pure love.. That is very precious.. Oh for more like you .thank you

Report comment

This is a stunning piece. I love what J and madmother13 say, and I agree wholeheartedly. Melissa, you are a gift to the world, and an example for it. Thank you ♥

Report comment