A new study finds that 86% of people will have met criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis by the time they’re 45 years old, and 85% of those will have met criteria for at least two diagnoses. Exactly half (50%) of the population will have met the criteria for a “disorder” by age 18.

According to the researchers, almost nine out of ten people will meet the criteria for “mental illness” at some point in their life.

This shockingly high rate of “mental illness” is not the focal point of the study. Instead, the researchers write that “these findings suggest that mental disorder life histories shift among different successive disorders.” That is, the implication of their study, according to the researchers, is that people with “mental illness” may have multiple different diagnoses.

The research was led by Avshalom Caspi at Duke University and published in JAMA Network Open.

Caspi and co-authors used data from the Dunedin Study, a population-representative study that followed 1013 people born in Dunedin, New Zealand, in 1972-1973. Trained health professionals conducted in-depth interviews when the participants were 11, 13, 15, 18, 21, 26, 32, 38, and 45 years old in order to assess whether participants met the criteria for any psychiatric diagnoses. The researchers do not specify whether this diagnostic process could have overdiagnosed “mental illness.”

Caspi and co-authors used data from the Dunedin Study, a population-representative study that followed 1013 people born in Dunedin, New Zealand, in 1972-1973. Trained health professionals conducted in-depth interviews when the participants were 11, 13, 15, 18, 21, 26, 32, 38, and 45 years old in order to assess whether participants met the criteria for any psychiatric diagnoses. The researchers do not specify whether this diagnostic process could have overdiagnosed “mental illness.”

Even more startling, the researchers report that 17 people reported receiving mental health treatment but were not captured as having mental illness by the interviews; one of those people died from suicide.

The researchers found that almost four times as many subjects met criteria for schizophrenia than is usually estimated in a population (3.7% versus 1%); a whopping 15% of the participants met the criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder (usually estimated to have a population prevalence of 2-3%).

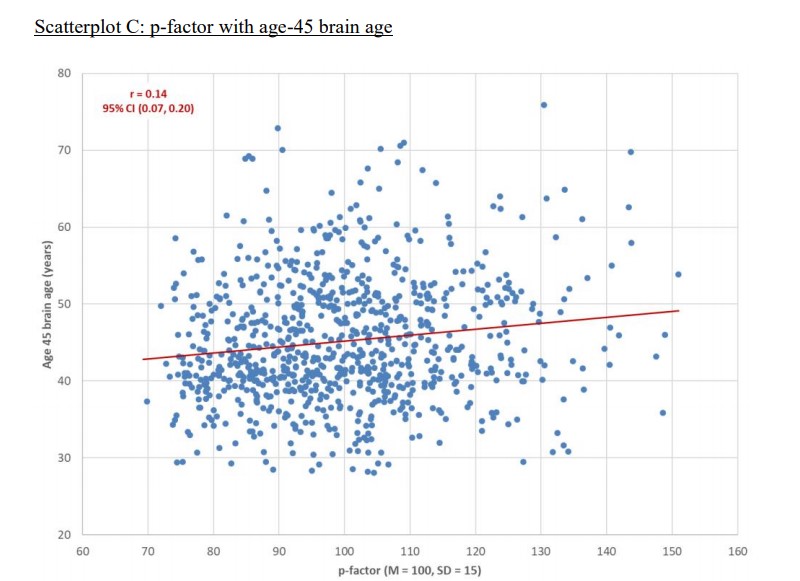

The researchers also write that they “tested the hypothesis that mental disorder life histories, summarized by the p-factor, reflect compromised brain function.” The comparison is unusual since almost everyone in the study had a “mental disorder” at some point, but they conducted a large number of statistical tests, breaking down the people with “mental disorders” into groups such as those with “externalizing” versus “internalizing” symptoms, or those with more diagnoses versus those with fewer. They also used measures of supposed “brain ages,” despite questions about the validity of that measure.

All of their results were “statistically significant” but explained very little. For instance, see the scatterplot below:

In a plot like this, the impact of a finding is demonstrated by how tightly the points (each dot representing a research participant) group around the line. In this case, the dots are scattered widely, and the correlation is minuscule. Some people with “brain ages” in the 70s, for instance, still had the lowest p-factors (likelihood of the most impairment from psychiatric problems), while some people with “brain ages” in the 30s had the highest p-factors. However, this data is reported as statistically significant findings.

The researchers do not address the possibility of overdiagnosis, or of how the broadening of diagnostic categories in each successive edition of the DSM could lead to the pathologization of more and more normal experiences.

Instead, they suggest that their analysis is more accurate than most estimates since they were able to follow a whole representative population cohort from birth and their detailed interviews captured populations that are usually missed, such as homeless people and those not receiving mental health treatment.

****

Caspi, A., Houts, R. M., Ambler, A., Danese, A., Elliott, M. L., Hariri, A., . . . & Moffitt, T. E. (2020). Longitudinal assessment of mental health disorders and comorbidities across 4 decades among participants in the Dunedin birth cohort study. JAMA Netw Open, 3(4), e203221. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3221 (Link)

This will be a little off topic but I want/need your advice/opinions. A few months ago I read Robert Whitaker’s book “An anatomy of an epidemic” and began frequenting this website. I am now withdrawing slowly off these drugs and despite the withdrawal effects I feel better. I used to wake up every single morning wanting to die for hours. Since I significantly dropped my dosage I no longer want to die.

However I am suffering trauma from the atrocities these drugs have done and are doing to me and millions of other people. I befriended a lot of suffering people through the mental health care industry. I still have contact information and could track down contact information for some of these people. I feel a need to help them by telling them the dark truth about the drugs. I need advice regarding that and I don’t know where else to get it besides here.

I realize that probably all of them will think I’m a “crazy” person and my efforts will accomplish nothing. But the result of doing nothing is the same as failure. The only chance to do good is to try. So any personal experiences, thoughts or advice regarding that subject would be appreciated. Thank you.

Report comment

First off, I’m glad you feel better. It can be a long road.

I think as far as people you ‘know’ online, as best as we can know them, it is good to tread carefully, as in slowly.

You could simply share your path, your conclusions and give them links to different articles, websites and also impress how important it is to have info on drug withdrawal or also a support system that is trustworthy.

I think it is also important to impart on people that they might continue to “suffer”, or feel “depressed”, sad etc. That absence of “mental illness” paradigm, does not mean humans do not run into bouts of difficulty.

Also that it is not a failure to be on drugs, but it is imperative that they don’t inherently believe something is “wrong” with them, or that they are ill….

Psychiatry basically has changed even grief into something “abnormal”, yet they have no pills to make people happy or grief free.

They have harsh chemicals that disrupt the brain, that is all they have. Do they help some? perhaps some think they do, but perhaps even just a short while.

You can empower people with info, choices, and it takes time for people to digest the idea that they are not “mentally ill”.

Report comment

It is pretty common for people recovering from a traumatic experience to want to help others do the same. I’d say you’re on the right track in contacting people who have experienced similar things. I wouldn’t waste a lot of time on the “true believers” who can’t consider anything but their own rigid beliefs for fear of their world collapsing, but there are plenty of people who are “on the fence” or who haven’t been helped as promised or who have deteriorated in “psychiatric care” who need people like you to help them out. It’s just a matter of connecting with such people, which isn’t always easy. I also think it’s very important to stay connected with others who agree with your view of things so you don’t start feeling like you’re the “only one.” MIA is really good for that.

I hope someone who has been exactly where you are can chime in and share how they managed to move forward after this kind of trauma.

Report comment

I have tried to convince some of my friends who take psychiatric drugs about their possible dangers without any luck. I have a friend who even started her son on “ADHD” drugs, which turned out to be a gateway drug and diagnosis which led to further drugs and diagnosis, much like my own story. In all this, it’s good to remember that even drug addicts still have a human spirit that can overcome a lot of harm.

One of the things that I hope to address in the book I am working on is the widespread, mainstream deception in the Western world by the mental health industry–how it works and counter arguments. I bought into it myself for so long and deeply, so I have a pretty good understanding of these things. So many people have so much invested in being mentally ill, calling other people mentally ill, and being mental health providers that it can be nearly impossible to break through those ideologies. Popular opinion needs to change.

Maybe you could think of it as trying to convince someone to quit smoking. However, the dangers of smoking are widely known, and quitting abruptly doesn’t cause potentially disastrous withdrawal effect. Educate, inform, encourage, but support the friend for their innate value, regardless of their choices.

To sum up, I’m sorry, I really don’t have any helpful advice for you regarding how to warn your friends of the dangers of psychiatric drugs. I haven’t had any success in doing it. Maybe you could give them a copy of Anatomy of an Epidemic and hope for the best. Good luck!

Report comment

Willoweed, been where your at. You might want to read these as they might more fully inform what you’re experiencing from a ‘fellow traveler’ who needed a bigger picture and more informed Iintel on the entombment that lasted 14 years …or ‘How did that happen to ME’?

I’m out, with guided withdrawal (with ‘aftershocks’), an official, DOCUMENTED VACATED “lifelong SMI diagnosis”, and am doing really, really well. (“A Unicorn: Changing a Diagnosis” RxISK.org 2018 and “Full Moral Status” MIA 2019).

I’ve done some peer counseling regarding how to effectively ‘fight the power’ with SAFETY within the industry, the first principle.

After 5 years of research and healing, these are some enlightening, supportive, and validating writing….

“The Latest Mania: Selling Bipolar Disorder” David Healy PLOS Med, 2006… also NIH.

Nailed it and made my weep…my story.

“The Book of Woe: The DSM and the Unmaking of Psychiatry” Gary Greenberg 2013.

Nailed it with snarky black humor.

“Cracked: The Unhappy Truth About Psychiatry” James Davies 2013.

A UK version of nailing it.

BTW, I found it very tricky to ‘assess’ other’s emotional challenges. I listened to what they wanted, contrasted with the ‘listeners’ in the industry. I found that sharing my strategy and tactics to assert my rights and insistence on TRANSPARENCY and SAFETY per THE INDUSTRY’S OWN RULES, STATUTES, AND LANGUAGE was paramount…and possibly first steps to regain their confidence and ultimately, they’re power.

I found not everybody can or wants to get out, but they’re aware of the danger and their lack of a voice. They need some coaching (I certainly did)…as they’re drugged and their ‘caretakers’ ostensibly are not. Big handicap when you’re negotiating safe care for your brain.

If they were ‘game’ to make a calculated run for it, I gave them resources and tactics that worked for me to achieve my freedom, a changed ‘diagnosis’ (Anxiety!) and the fantastic rest of my life…Their choice to use, modify, or discard.

Good luck

Report comment

Sounds like a great approach for being truly helpful to another person!

Report comment

I’m not very profound, as some of the regulars may tell you, but I do know that the antipsychotic movement problems (dyskinesia, akathisia) you and others might be having can (at least sometimes) be treated with manganese salts, preferably by an orthomolecular medical guy, but I can propose a starter program if you can’t find a practitioner (you don’t want to do this without guidance, as manganese can do bad things in excess).

Report comment

“According to the researchers, almost nine out of ten people will meet the criteria for “mental illness” at some point in their life.”

Well since the “mental health” industry believe that all dreams, gut instincts, and even thoughts are “psychosis,” that would imply 100% of people should meet the criteria for “mental illness.” But at what point does the “mental health” industry look stupid and absurd? Not to mention criminal, since the primary actual societal function of both the psychologists and psychiatrists is covering up child abuse and rape.

https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/01/23/18820633.php?fbclid=IwAR2-cgZPcEvbz7yFqMuUwneIuaqGleGiOzackY4N2sPeVXolwmEga5iKxdo

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

And all this illegal child abuse covering up – and, of course, subsequent pedophile aiding, abetting, and empowering – is by DSM design.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-child-does-not-have-bipolar-disorder/201402/dsm-5-and-child-neglect-and-abuse-1

The “mental health” industry must be so proud of the “pedophile empire” they systemically helped to create?

https://www.amazon.com/Pedophilia-Empire-Chapter-Introduction-Disorder-ebook/dp/B0773QHGPT

And at what point do we say to the “mental health” industry, you’ve killed too many innocent people? “8 million people die each year due to” their “invalid” “mental illness[es],” and no doubt, due to their neurotoxic psychiatric drugs.

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2015/mortality-and-mental-disorders.shtml

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml

That would amount to the systemic psychiatric slaughter of approximately 400,000,000 people over the past 50 years. It’s past time to end the systemic, psychiatric slaughter of innocents.

Report comment

Thank you Peter for your all your work.

We are tired of arguing the obvious, and as cults go, one cannot argue with them.

I am encouraged that this phenomena called “mental illness” is now affecting psychiatrists and a HUGE number of nurses and doctors, teachers and politicians. Percentages don’t lie, do they.

Report comment

Obviously, a business decision. If we can convince enough people that they are sick, in need of lifelong psychiatric drugs, therapy, mental hospitalization, institutionalization, group homes, the lives of the sane, normal mental health professionals can only get better and better by comparison.

Report comment

Caroline I agree, well said.

Magdalene

Report comment

Thanks, Magdalene!

Report comment

It’s kind of mind-blowing that the authors of this study don’t even consider the concept of overdiagnosis, given their results. It’s pretty obvious to me that if almost everyone qualifies as mentally ill at some point, then no one does. It’s a meaningless concept.

Or rather, if we define MI as a deviation from the norm, but clusters of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors so defined turn out to be so common that they ARE the norm, then we should now define anyone NOT meeting the criteria for MI as mentally ill.

The idea that we as a society allow a small guild (APA) to decide who’s normal and then build a “scientific” research enterprise around that is absurd.

Report comment

Once we allow for subjective “diagnosis” based on observer opinions, there is no end to who and what may get “diagnosed.” I think that’s the clear and obvious conclusion from this observation – when there is no objectively definable line of “normal,” sooner or later, everyone is diagnosable. Which, as you say, makes “abnormal” the new normal!

Report comment

Great points, Miranda! Maybe the psychiatrists who wrote the DSM should be locked up and forced to take drugs for their own good, of course, so they can be more normal.

Report comment

I agree with Miranda.

It would be good to see some form of major public international enquiry, on how and why legal justice systems, insurance companies, courts, judges and state parliaments around the world – legally endorsed the DSM in the first place?

Report comment

I think these institutions just assumed that psychiatrists were on the up and up and took them at their word.

Report comment

“It’s pretty obvious to me that if almost everyone qualifies as mentally ill at some point, then no one does.”

Why?

Would you also say that “It’s pretty obvious to me that if almost everyone qualifies as physically ill at some point, then no one does”?

It’s quite common for people to have physical maladies. For some people, it’s temporary, and others have chronic physical health conditions (e.g., high blood pressure, asthma, epilepsy, diabetes, cerebral palsy, blindness, deafness, muscular dystrophy). Offhand, I don’t see why the same wouldn’t be the case with mental illness: that it’s common, and for some people it’s temporary, and for others it isn’t. However, that doesn’t imply that we understand mental health conditions as well as physical health conditions in terms of diagnosis or treatment.

Report comment

Perhaps she was referring to the high percentage which points to a very good chance that you and I and our “caregivers” are “mentally ill”.

And then of course there are opinions that people are “mentally ill”.

Report comment

Diagnosis shifter, eh? That’s a good one. Are you a wereschizophrenic, or a dual genus lifeform (AKA bi-polar)? Or are you just an amorphous diagnosis shifter? And, no, medical doctors don’t have anything to do with that sort of thing whatsoever. It’s all *cough, cough* about the “science”.

Report comment

“For the purposes of this Act a person has a mental illness if the person suffers from a disturbance of thought, mood, volition, perception, orientation or memory that impairs judgment or behaviour to a significant extent.”

significant extent being a very subjective term. Consider the state of mind when one sneezes. Thus the whole country is mentally ill, and I therefore call for all legislation passed through our Parliament to be repealled (as it was passed by mad white men) and the land be handed back to it’s rightful owners, the Chinese. lol

Report comment

Thank you, Peter Simons, for bringing this article to our attention. A lifetime prevalence rate of 86% for mental disorders? Something is seriously wrong with our society.

Report comment

Popular opinion needs to change.

Report comment

Due to my unfortunate, past ‘relationship’ with the industry (Bipolar 1/SMI) and the 6 years of subsequent research while recovering following my self-rescue, here is what I can offer…

“Overdiagnoses” are a result of financial manipulation by Pharma, the trickle down of billions to the APA ($30 million { , _} annually), publishers of the DSM-molding criteria to new and ‘rebranded’ {off-label} product, ‘research and consulting’ graft to psychiatrists to diagnose appropriate to the new drugs hitting the market (ProPublica “Dollars for Docs”).

Psych comprises #1 or #2 (fluctuation over a decade) positions of receiving sheer amount of $ compared to any med specialty), and Big Insurance who happily, successfully herd any client towards ‘pit stop’ psychiatry (drugs), effectively nullifying qualified therapy as an option for most.

All of this is easily achieved as Pharma is the #3 contributor to The Hill, following ‘Energy’ and Wall Street. Big insurance is happy to collude. And EVERYBODY sucks the teat of government programs, Medicaid and Medicare.

The poor and the old are especially targeted and drowned in psychotropics-sedation-increased mortality as a result of under representation. Clean-up on aisle 1…or the non-voting constituency. Who cares?

The judiciary requires ‘definitive’, ‘authoritative’ language to deal with DTS/DTO…and folks who are just different. Never mind that psychiatry is a self-annointed authority. Courts do not like ‘loose threads’ and, like medicine, loathes the sentence “I don’t know”.

Psychiatry is grateful for the ‘legitimacy’ bestowed by the ultimate authority, the courts.

Perfect symbiosis.

Life goes on and it is good for these guys.

Commerce, retail, marketing. Define your market, label (legally!) as ‘lifelong’, rule with a gloved fist. (“Isn’t stigma awful? Fight Stigma!”).. with fear of death-suicide-for non-compliance.

The definition of a cult is… agenda, proselytize, recruit….and rule with fear. Done and done.

The falsely generated (thanks Allen France$!) bipolar ‘epidemic’ following the 1995 DSM IV is textbook Harvard biz school 101.

See Time magazine’s cover story (2002) “Young and Bipolar” detailing the U.S. pediatric bipolar explosion of bipolar diagnoses from 40,000 to 800,000!!! following publication. Adult diagnoses tripled…only in the U.S., not Western Europe. And people wanted the pills as they weren’t informed about the probable consequences. Hell, the INDUSTRY wasn’t sure about short-term, long-term prognosis…too busy counting cash. The FDA also has a $ymbiotic relationship with them.

My diagnosing doctor gave me a 20-minute assessment before labeling and drugging me-for-life (presenting with insomnia from financial stress..and GREAT insurance). She gave me a combo-platter of drugs that day featuring Seroquel, off-label (at that time-schizophrenia scrip).

I was in the hospital by nightfall with Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome, paralyzed for 8 hours. When I was told to ‘shake it off’…she. gave. me. more.

She was taking $65,000 a year from Pharma (“Dollars for Docs” listing), her biggest donor was Astra Zeneca, makers of…wait for it…Seroquel. Chemo for a cold.

IWhelp, it went down from there…. for 11 years, passed around the industry, ending up in state/Medicaid clinics. No Bueno for me.

Check it out…..

“Bipolar Disorder: The Shift to Overdiagnosis” U.S. National Library of Medicine 2012

“Some Conditions Misdiagnosed a Bipolar Disorder” Amy Norton Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2016

“Overdiagnosis of Bipolar Disorder: A Critical Analysis of the Literature” U.S. National Library of Medicine 2013

“The Increasing Frequency of Mania and Bipolar Disorder ;Causes and Potential Negative Impact” NIH 2012

My 2 faves…

“The Latest Mania: Selling Bipolar Disorder” David Healy PLoS Med 2006 **** CRYSTAL CLARITY of the hustle***

….and for some alarming, black humor that speaks to the industry as a whole…

“UNPECIFIED MENTAL DISORDER? THAT’S CRAZY: PSYCHIATRY’S DIAGNOSTIC BIBLE HAS BROADENED THE DEFINITION OF MENTAL ILLNESS TO ABSURDITY’ Leonard Sax, Wall Street Journal 2015.

BTW…my ‘exit’ diagnosis was.’.UNSPECIFIED ANXIETY’…I am a huge fan of irony.

Bruce McEwen, PhD, “The Hostage Brain” introducing me to the term/concept ALLOSTATIC LOAD.

It is important in this discussion. I hope you check it out..

Report comment

LOL! Derp! Once you accept the premise that feelings are a threat, you’re, literally, on your way to quacking out ANYONE!

Good on you for quantifying a human cost to psychiatry’s grift.

Report comment

You don’t fit our criteria for “serious mental illness”. What’s wrong with you!?

Report comment