The main reason given for depriving a person of his or her liberty by imposing involuntary hospitalizations and/or forced medication is that “the patient poses a danger to self or others.” The assessment that danger exists is then used to justify taking measures to alleviate the threat of harm. And if the danger is frightening enough, then risky measures can be taken that are themselves known to have a fairly high probability of causing significant harm. Danger must be minimized.

The lost art of deliberate clinical inertia: Don’t just do something; stand there!

Now, of course, when people are suffering, we should just stand there only when there isn’t anything more helpful we can do. Then, just standing by them as they suffer—keeping company with them and keeping them from feeling alone or abandoned in their anguish—may actually be doing something. It may be doing something despite how ineffectual and awful it feels not to feel like you’re doing something.

That awful feeling is actually another kind of danger when a person’s strange behavior appears to threaten violence. This is the danger to the clinician’s identity. When faced with a distressing situation, those who have studied and trained to make their meaning in life lie in their identity as healers often feel compelled to do something. If they don’t do something then they have failed at their chosen assignment in life. If the action then taken provides no benefit—and even if it makes the situation worse—at least it reaffirms the clinician’s identity as an expert who doesn’t just stand by passively when faced with human suffering.

In their struggle with these dangers, some leading psychiatrists have even justified the prescription of drugs that are known to increase suicidal thoughts and feelings to treat suicidal thoughts and feelings! And they can do that despite the fact that those drugs (the antidepressants) have been shown to be no more effective than a placebo for the vast majority of patients for whom they are prescribed.

Whether or not the evidence supports the belief, in order for good folks to force treatment on others, they do have to believe that the measures they employ are effective, meaning that they will do more good than harm. However, when that belief is applied to the use of “antipsychotics”—I put the word in quotes because in and of itself it implies effectiveness—we see that the research (even that produced by advocates of medication) does not support the conviction. Thus, the actors must deceive themselves in order to (forcefully) sell dubious, dangerous treatment. This is an example of the evolutionary principle of self-deception in the service of deception.

Indeed, assessing danger and treatment effectiveness involves judgments that reveal as much, if not more, about the one doing the assessment than the one labeled as being at risk. The research shows that the only folks who consistently benefit from the coercive use of antipsychotics and involuntary hospitalization are the ones selling the drugs, running the hospitals, and doing the prescribing. While the cautious, limited use of hospitals and medications appears to benefit some patients some of the time, reliable benefits accrue to the doctors, hospitals, and pharmaceutical companies. Objective measures suggest that, despite the benefit that some may receive (and for whom judicious use of the treatment could be justified), on average, such standard treatment makes life worse for the majority of patients, especially those on whom the treatment is forced.

Stranger danger

In an earlier article, I suggested that there is one thing folks who receive a label of psychosis have in common: The social surround finds something strange about their behavior or statements. They don’t conform to expectations. Therefore, they are “strange.” And I suggested that we have been designed (via evolution through natural selection) to feel that strangeness indicates possible danger.

If that is so—and especially if the standard treatment is more often than not detrimental—we need to be sure we are not over-assessing danger (1) because of a natural tendency to find strangeness somewhat anxiety provoking and (2) because of the assessors’ natural, self-interested bias. Regarding the latter, we must always be wary of the danger of Maslow’s Hammer: “I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.” And psychopharmacology is psychiatry’s hammer.

With this concern, in that earlier article, “A Phenomenological View of Madness and Medicine,” I looked at the interaction between stranger=danger and self-interested bias when it comes to mental health treatment. But first I felt compelled to acknowledge that there is, in fact, a higher rate of violence committed by folks who are labelled psychotic.

The association of “mental illness” with violence and the correlation-causation fallacy

You see, John Monahan, a prominent psychologist whose work was often cited in legal opinions exploring the validity of expert predictions of dangerousness, had long championed the notion that serious mental illness was not associated with increased violence. More recently, however, he felt forced by the data to change his opinion:

The data that have recently become available, fairly read, suggest the one conclusion I did not want to reach: Whether the measure is the prevalence of violence among the disordered or the prevalence of disorder among the violent, whether the sample is people who are selected for treatment as inmates or patients in institutions or people randomly chosen from the open community, and no matter how many social and demographic factors are statistically taken into account, there appears to be a relationship between mental disorder and violent behavior.

The question remained, however, as to why there is a higher rate of violence committed by those diagnosed with major mental illness. I noted that there was also research that suggested that violence was not associated with mental illness directly, but rather with substance abuse. If those diagnosed as psychotic had a higher rate of substance abuse, then indirectly there would be an association between diagnosis and violence, with the latter being due to substance abuse, not psychosis.

This is an example of the correlation-causation fallacy: Mental illness apparently is correlated with increased violence. But the problematic factor is not the “illness” per se; rather the problem may be the attempt to escape from the pain of psychotic experience using drugs. In fact, other research showed that those diagnosed as psychotic who also have a history of substance abuse are not more likely to be violent than those involved with substance abuse without a psychosis diagnosis.

Who started it?

Furthermore, when medication is forced upon a person, physical struggles against the aggressors occur. Indeed, if force is used, then the existence of such struggles is tautological. And when such struggles cause injury or other serious problems, they are then considered examples of dangerous behavior on the part of the patient. This alone would lead to a correlation of psychosis and violence.

If you think that’s farfetched and medication and other forced treatment struggles couldn’t be common enough to account for the association between a major mental illness diagnosis and violence, then you haven’t been involved in the mental health system. To illustrate the problem, I described a patient whose “treatment [was] focused exclusively on ‘medication compliance.’ It, and nothing else of substance, was on every page of Henry’s hospital, treatment record.” At first, folks may feel a person is acting strangely. When they then try to control that person’s behavior with force, is it not possible that they are causing the violence that ensues?

Let’s leave that possibility aside and return to the research findings that show associations between diagnosis, substance abuse, and violence. As noted, the earlier empirical evidence suggested that the direct problem associated with violence was substance abuse.

A new study

Now, a new study supports the conclusion that it is substance abuse that accounts for the increases in violence and not mental illness. Using recidivism (the rearrest rate) of releasees as the target measure, the authors reviewed the data from 10,000 New Jersey state inmates released in 2013.

What they found was that those releasees who had been identified as having a mental illness but who lacked a history of substance abuse had the lowest rate of recidivism, even lower than those who had no history of substance abuse and no diagnosis of a mental illness.

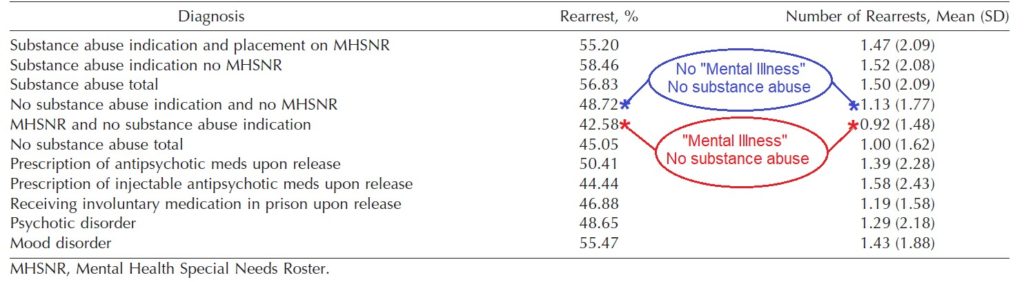

Rearrest by Diagnosis (from Zgoba, et al., 2020)

Comparing the rearrest rate of those with a “mental illness” and no substance abuse history (.92) with those with a mental illness diagnosis and a substance abuse history (1.47), we see a 160% greater rate when both elements are present. The difference is statistically significant (two-tailed p=0.0016). The driving factor does appear to be substance abuse, not mental illness.

What about antipsychotic meds?

A claim could be made that antipsychotic medication accounts for the low rate of recidivism among those releasees with a mental illness diagnosis and without a history of substance abuse. However, only a fifth of those diagnosed as mentally ill had a prescription for antipsychotic meds upon release. In the CATIE Study (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness), close to 75 percent of the patients discontinued their medications during the 18 months of the study, confirming that antipsychotic compliance was the exception, not the norm. Thus we can be fairly sure that relatively few releasees—most likely well under 5%—with a mental health diagnosis took antipsychotic medication regularly during the three years (36 months) of this study.

Furthermore, from the data presented in the research report I was able to calculate the average number of rearrests per releasee with a mental health diagnosis with and without prescriptions for antipsychotic medication. When this is done, we find that the average number of rearrests was almost exactly the same (1.4) for both those prescribed antipsychotic medication as well as the unmedicated group. Antipsychotic medication—with its known risks and dangerous, long-term side effects—had no effect on the rearrest rate.

One policy conclusion that could be drawn from this study is that the attempt to use drugs to make mental patients less dangerous is the exact opposite of what is needed. What we need are effective programs that reduce the use of all unnecessary, harmful drugs, including the antipsychotics.

.

Report comment

Hello, Daniel Kriegman. This is Jeffrey, the same “crazy” Jeffrey you… corresponded? With in the 2000’s quite a bit. The one that once blew your mind regarding something to do with emails.

I’m glad you’re still alive, and hope you are doing well. I am better than ever, and pushing further every day.

This is where I’m at in life: https://youtu.be/6_vzD8rWgas

You once “treated” me as a “professional”, with the ultimate “conclusion” being, narrowly summed up, that I needed a partner. And you were right. Unfortunately, that’s never happened. It’s the “last” thing I need to “complete” my “recovery”, but with where I am at right now…

Here’s a fun one for ya! https://youtu.be/DC42g6mRGUI

And you were right; life is trouble; https://youtu.be/07ytbMU5oXU XD XO XD No but seriously, I’m one the edge, feeling like a spiritual successor to Hunter Thompson.

I never did pay you for your online “therapy”, it doesn’t feel right considering how much it has guided me to where I’m at now. Get ahold of me.

Report comment

BBC News – US Supreme Court backs protection for LGBT workers

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-53055632

“..An employer who fires an individual for being homosexual or transgender fires that person for traits or actions it would not have questioned in members of a different sex,” he wrote…”

Society is full of potentially gratuitously dangerous people without “Mental Illness”. Whats so special about the “Mentally Ill”?

Report comment

In my opinion the Epidemic in Irish Suicide and Familicide can be directly traced to the commonplace use of Psychiatric Drugs in the “normal population”.

Report comment

Thank you Dan.

It begs the question. Is it better to be predictable or unpredictable? Aren’t we all unpredictable?

And it is why it can be dangerous to hire a cop, give him a gun.

It is why it is dangerous to see a shrink. He has possession of very damaging drugs.

It is why it is dangerous to have weapons of mass destruction in the fingers of politicians.

It is why it is dangerous to place power into the hands of those who rule over others.

In this way, everyone is dangerous, but the ones that hold the most power are ultimately the most dangerous. They hold the ability and do so, to seriously harm thousands.

Report comment

I agree, forced treatment is violence. The doctor that medically unnecessarily force treated me was eventually convicted by the FBI for fraud, because he was medically unnecessarily harming many people for profit

I also agree the antidepressants and antipsychotics are neurotoxins, harmful drugs. And thus the use of those drugs should be curtailed.

Report comment

“At first, folks may feel a person is acting strangely. When they then try to control that person’s behavior with force, is it not possible that they are causing the violence that ensues?

Let’s leave that possibility aside ….”

Lets not. Lets consider the situation where a ‘bait and switch’ is used. Where a person is not acting strangely but we want them to in order to justify our actions against them. We give the command to do to contradictory actions simultaneously. “Stand up, sit down” and the failure to comply is justification to place the person in handcuffs. Of course when we try to do that they ‘resist arrest’ and thus require the use of more force. So what happens when we beat them to unconciousness? Their ‘passive resistance’ requires the use of even more force, and there has been an unfortunate incident which will require medical intervention.

And with the ability of hospital Operations Managers to distribute fraudulent documents to lawyers and other relevant bodies wishing to investigate the matters? The sky really is the limit.

I think that as long as the data (and documents) are being tampered with, any story we wish to be true, will be. Personally I don’t consider being unconcious or dead as being “passive resistance” but there are others who are in positions of power who do. And with systems that follow the rules laid down by Machiavelli, that the ends always justify the means, nothing is going to change.

And as long as we stay busy discussing fraud? Who benefits?

Report comment

Yes the bait, it is employed more often than not. It comes in many forms but oh so obvious.

I have had to use psych 101 a few times.

Report comment

I see this discussion as somewhat glossing over the whole problem of lack of bravery in humans, as well as lack of understanding on the part of mental health professionals. This due partly to a few references to “evolution” which I don’t think has any bearing on this subject.

My argument is, on the one hand, that mental health professionals need to be trained to be “brave” in situations where they are dealing directly with people who are “acting strange.” We have all experienced situations like this. It is really not that uncommon. But most of us are not trained to maintain control in such situations in a professional manner. Mental health workers should be. And that means minimal use of force, as use of violent force or threats just escalates the situation, which is widely understood to be the case.

On the other hand, “acting strange” should not serve as a justification for the cowardly act of forceful restraint and injection, especially on the part of mental health professionals. We have to confront some of the less noble human traits in this regard. There is an element of psychosis in the action of restraining and drugging the “psychotic!”

I was interested in the distinction made between drug use and mental illness. I always considered drug use a form, or symptom, of mental illness. It’s one reason, after all, that some people “feel better” after taking a placebo. The pill gives the person a reason to feel better, an external cause, as they have lost track of their own cause in such matters. Of course, an illicit drug habit tends to result in over-spending for more drugs, and then the temptation to steal, and thus to commit violent acts. I would like to see if the study took into account what exactly the person was arrested for doing and in what context.

As for meds, I would have thought they would have increased the chances for rearrest, not decreased them. These meds have violence as one of their (side) effects. But most in this study weren’t on meds, or they were attempting to “self-medicate.”

So I’m not sure what the point of all this is. Drug abuse, mental illness and “acting strange” are all correlated. Society wants those people off the streets and out of sight, and they hire mental health workers and police to do that. Society dictates the way those people are handled, as much as do the workers who must deal with such people directly. If the results are damaging, then it is society which is psychotic, not just the police or the mental health workers, or the “mentally ill.”

Outcomes from interventions can be improved by re-training the people who engage in such interventions. That much is clear from the Open Dialog experience in Finland. But who will re-train the rest of society? Last I knew, Open Dialog was only in use in very limited areas. Yet it works much better than “standard” interventions. So we have a problem in society in general as well as in the field of psychiatry. It could be seen, itself, as a kind of psychosis.

Report comment

“If the results are damaging, then it is society which is psychotic……….”

Report comment

“There is an element of psychosis in the action of restraining and drugging the “psychotic!””

Certainly what I observed from Dr “i’m the Boss around here” just before he found out he wasn’t the Boss around there and had to leave his little task assigned to him by one of his Bosses. He really needs to learn to disguise the psychosis which shows in his eyes while he murd …. I mean unintentionally negatively outcomes people in the Emergency Dept.

“But most of us are not trained to maintain control in such situations in a professional manner.”

So true. Nurse, could you give this to patient X? I guess they get a little eager, and ‘hands on’, when they’re young.

Report comment

https://youtu.be/ppQdFRRo9UE

Acting Very Strange

Is Acting Very Human.

Please people can we stop with the “meds” business? THEY ARE DRUGS.

I know that this article is meant to distinguish between “taking your meds” and “seeking illicit drugs”

But psych drugs are NOT medicine.

Report comment

HearHear! Jan

One could only consider a drug as “medicine” if one found it helpful, and it did no harm.

When one is in nature and finds it soothing, it could be appropriately referred to as,

“that was the perfect medicine for me”

Report comment

And is there in fact such a distinction, other than in terms of legality?

Report comment

If provided to someone in a nite club they are considered to be one of a class of intoxicating substances and the act of providing them (without knowledge) is considered a crime (intoxication by deception, and if used to commit a further offence say kidnapping or sexual assault, then stupefying with intent to commit an indictable offence).

But if they are provided to a person who has the status of “patient” and they willingly take them of their own volition (actually in fact after the way police have dealt with my matters even if you are ‘spiked’ with them) they are considered medicine. It an interesting means of making what are considered criminal acts appear to be lawful, that is ‘spiking’ someone and then having a doctor commit the offence of conceal evidence of a crime and attempt to pervert the course of justice by signing a prescription post hoc. It actually opens up the possibility of police being allowed to use known torture methods and can then change the status of the person who has been tortured to one of “patient” and the allows them to be forced into ‘treatment’ to conceal the acts of torture. Not that those without a “sophisticated knowledge of the law” (Head of the AMA) would understand how to conceal these acts of State sanctioned torture as ‘medicine’.

I like the way the Community Nurse went through some verbal gymnastics with “substances, chemicals, medicines and drugs during his slandering of me in his documentation. The “spiking’ of me with benzos an act of medicinal necessity, whilst my refusal to answer his questions regarding any ‘medications’ I might have been taking was documented on his statutory declaration as being “refused to answer re substance abuse” (something a lawyer would recognize as being no “reason” to be locking someone up for further questioning. Not in my State of course which has arbitrary detentions for mental health professionals due to the negligence of our ‘protector’ the Chief Psychiatrist. Refusing to answer a question by a public official grounds for the administration of intoxicants without knowledge and the use of weapons to cause an ‘acute stress reaction’ before interrogation aka torture if it were done by the Ghanaian government, but not if done by a 5 eyes Nation apparently).

So I’m with you Jan, drugs not medicine. And as I have pointed out to our current Minister for Health these were acts of torture and kidnapping NOT “referral and detention”. It’s a matter of preferring them to be considered ‘medicine’ whilst the person is made into an addict, and then revealing one self when they attempt to stop taking these drugs and begin to suffer from withdrawal symptoms. And likewise making questions of law, questions of ‘medicine’, not unlike the child raping priests whose victims had no right to make complaint (they were after all not considered to have legal or mental capacity)

Steppenwolf said it best

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sTss9K0LXJ0

The Pusher is a Monster, loves to leave your mind to scream.

Report comment