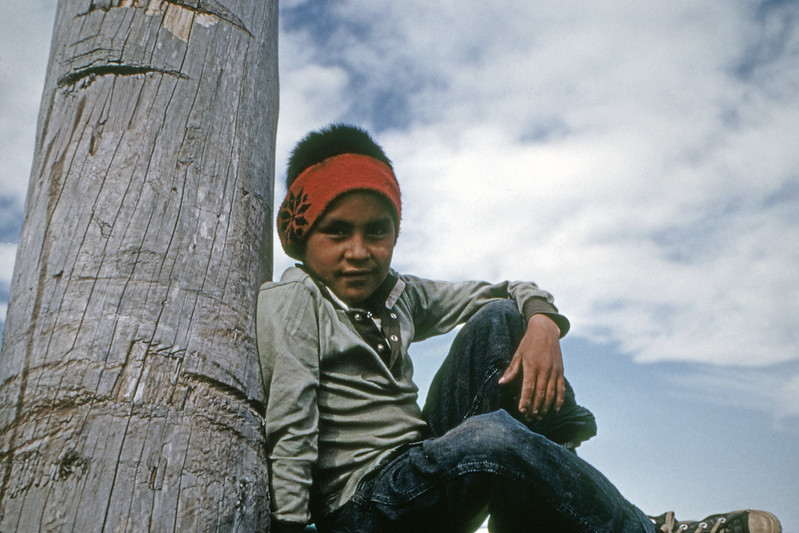

Traditional psychiatric care has failed to address the increasing rates of suicide among Native Alaskan youth in the Arctic. In response, researchers from Harvard and the University of Michigan studied how suicide is locally understood and how culturally responsive and human rights approaches to mental health could be applied in this setting.

The researchers, Lucas Trout and Lisa Wexler, published their findings in the Health and Human Rights Journal. They report that while suicide was understood by some as the result of “mental illness” (in line with the psychiatric model), it was also seen as a consequence of intergenerational trauma, social inequity, and relational factors (in line with the social model) by others. Trout and Wexler argue that suicide should be addressed through a social medicine and human rights approach to global mental health.

“Alaska Native youth suicide rates have become among the nation’s highest in the past 60 years . . . Paradoxically, the rise of youth suicide across the North American Arctic closely parallels the development of colonial infrastructure, including health systems and public services, in indigenous communities. Suicide rates have increased in tandem with the rapid and imposed social change that has characterized the ‘modernization’ of the Global North in various waves of colonial settlement,” the authors write.

“Rapid, imposed social change and the dissolution of shared structures of meaning are implicated frequently in public discourse, as well as some research, as drivers of contemporary youth suicide.”

Suicide rates are on the rise in the United States and across much of the world. Research has shown that suicide rates can increase when groups face systemic discrimination, including racial minorities, sexual minorities, and people who live in poverty.

Suicide rates are on the rise in the United States and across much of the world. Research has shown that suicide rates can increase when groups face systemic discrimination, including racial minorities, sexual minorities, and people who live in poverty.

While suicide is often approached as a psychiatric issue, research suggests people who use antidepressants are at higher risk of attempting suicide. On the other hand, evidence suggests that social interventions can reduce suicide levels. For example, suicide rates of low-wage workers are reduced when the minimum wage is increased.

Suicide rates are also on the rise in indigenous communities throughout the world. In Canada, the Nunavut people are ten times more likely to take their own lives than the general Canadian population. In Australia, indigenous people are five times more likely to do so. The social, economic, political, and historical ramifications of colonialism have been identified for contributing to suicidality within these groups. This is not dissimilar to the Alaskan context. According to the authors:

“The welfare colonialism embodied in health bureaucracies, public health infrastructure, and ‘Western’ forms of care is linked to the generation and maintenance of indigenous health disparities, including suicide. In response, Alaska Native leaders have called for community-based and decolonizing approaches that emphasize the protective value of culture, traditions, and sovereign systems of care.”

Global mental health care efforts with culturally sensitive and decolonial lenses have adopted indigenous healing practices and adapted their interventions by changing their discourses on suffering, utilizing local knowledge, and addressing their relational, cultural, and sociopolitical needs.

In this study, the researchers were interested in understanding how health and mental health professionals make sense of Alaskan Native youth suicide, the systems that influence how these professionals work, and the communities that they work within. The study aimed to better define the issue of suicidality in this context and to explore alternative approaches to reducing suicide rates. Trout and Wexler interviewed health professionals and analyzed their transcriptions and also draw on twenty-five years of clinical, research, and policy experience.

Their results were summarized as oppositions: (1) psychiatric vs. social explanatory models for mental health, (2) bureaucratic and relational forms of care, and (3) biomedical vs. biosocial models of care delivery. These binaries were identified as a tool to more simply explain complicated and complex layers of data.

Explanatory Models: When discussing explanatory suicide models, interviewees talked about being guided by interventions that are based on psychiatric knowledge and beliefs, even as they personally believed that social and structural factors were at the basis of suicidality.

Social explanatory models imply that social determinants cause suicide, but it also involves a sort of social logic to suicide. For example, while some talked about suicide as an outlet for the negative cultural and relational experiences individuals suffer, others highlighted how suicide could be used for social benefits such as seeking the attention of others.

There were also differences when addressing alcoholism as a factor of suicidality. For non-Natives, alcoholism was seen as a cause of suicidality, while Natives saw the relationship between alcoholism and suicidality as mediated by the sociohistorical conditions.

Care: When referring to forms of care, health professionals mentioned being burdened by the limits of their profession and by bureaucracy. Within a bureaucratic system of care, health workers were seen as professionals who used predetermined decision trees to make clinical judgments.

In contrast, within a relational model of care, “the individual matters specifically, emotively, and contextually. Acts of care emerge in this sense from an active relationship that itself establishes one’s capacity to help.”

The participants understood that Native clients have needs that cannot be attended to within the limits of their professional role. They saw their professional roles as insufficient for alleviating suffering and reducing suicidality. One of the participants, who was an Alaskan Native, removed a suicidal family member from clinical care and instead strengthened the child’s relationship with the family, land, and culture.

Systems of Health Care Delivery: While biomedical systems of care focus on delivering accurate and timely diagnoses of categorized diseases, biosocial systems attend to the social factors that influence distress, the personal or individual distress they cause, and the barriers to accessing efficacious treatment.

In Arctic Alaska, biomedical treatment of suicidality often involves isolating the person in a room, miles away from their community, and removing the person from lethal weapons or items so that they cannot hurt themselves through physical restraints. Afterward, they are referred to local mental health services, but these are underutilized due to skepticism about their relevance and utility, and the rejection of bureaucratized biomedical care. The authors explain:

“While there was a notable lack of consensus regarding what a truly biosocial care system might look like in the context of mental health, key recommendations included addressing the social determinants of health at the root of mental, emotional, and social suffering; attending to cultural safety in existing care systems, and supporting the community- and culture-based healing initiatives in addition to formal clinical care.”

This study highlights the limitations of suicide prevention and treatment for Alaskan Natives when the standardized “care” system is based on traditional psychiatric care and Western cultural norms. The authors call for a redefining of suicide care so that it can be tailored to the culture, history, and needs of this community and its neocolonial context.

“Suicide care involves navigating within caring relationships through the most practical and exigent of risks, the prescriptive nature and practicalities of care systems, and the complex social conditions that give rise to the level of suffering that suicide inherently marks.”

Additionally, the authors suggest the promotion of social medicine and human rights in global mental health care. This implies addressing the social determinants of mental health, in this case relating to colonialism and its broader cultural, social, political, economic, and relational effects.

A social medicine and human rights approach also involves providing care that goes beyond the technical and bureaucratic – that attends to moral and emotional needs, is person-centered, and understands the meaningful role of the patient-caregiver relationship.

****

Trout, L. & Wexler, L. (2020). Arctic Suicide, Social Medicine, and the Purview of Care in Global Mental Health. Health and Human Rights Journal, 22(1) (Link)

“the authors suggest the promotion of social medicine and human rights in global mental health care.”

Until forced psychiatric treatment, which is the epitome of a human rights violation, is eliminated. The “mental health” industries will never have a “human rights” based system.

Report comment

We need to find the people who have our lives inside them, and their lives are inside us, where we belong to each other. When life has so many distractions that we fail to meet one another in depth, then we’re in a lot of trouble.

Report comment

Psychiatric Care Fails to Address High Suicide Rates of Native Alaskans. Psychiatric care as I understand it might make matters worse.

Report comment

As long as they look for suicide within a person or even their close community or lack of, we won’t find the reasons. The subject is only a reflection, and becomes the diversion, but they do create jobs.

Silly society to benefit from it’s own harms.

Report comment