In the United States and abroad, a growing number of groups have devoted their mission and mindset to rethinking psychiatry, doing their best to encourage dialogue on the mental health system and the pressing need to fix it.

One such group, based in Portland, Oregon, has stayed the course for a decade. Along the way it’s offered platforms for conversation and resources for learning, growing, questioning — all necessary ingredients for change. It’s weathered challenges and adapted, even expanding its vision in the midst of pandemic.

Its name: Rethinking Psychiatry.

Education is a key component of what they do. Events are a related aspect. Building community is another. The project is as diverse and organic as it is committed to change, with all voices welcome and all viewpoints respected: Underscoring everything is a radical inclusivity. There’s no doctrine it pushes, no philosophy it espouses, no membership criteria it requires — nothing beyond a willingness to address the current paradigm and an openness to alternatives.

“All voices, right?” said Marica Meyers, the major force behind Rethinking Psychiatry’s creation. “All voices.”

In the decade since its creation, Rethinking Psychiatry (RTP) has offered symposia, regular meetings, talks, a film festival, and “Truth and Reconciliation” sessions inviting mental health caregivers and recipients to say their piece in peace. Its website, rethinkingpsychiatry.org, provides resources and links to other sites that challenge the pharmaceutical model of care and encourage different takes on mental and emotional well-being.

It’s given a platform to voices too often stifled in mental health discussions, including those with lived experience. And it’s given people in Portland — and lately, with virtual programming, people around the country and the world — a window into alternate approaches, such as the Soteria Houses in Vermont, Israel, and elsewhere that provide non-drugged, non-hospitalized therapeutic living for those experiencing psychosis. An in-depth look into Soteria Alaska, which closed in 2015, is slated for May 23.

Right from the start, the grassroots, volunteer-run group sought to welcome different perspectives — to empower them, not stifle them — in an effort to promote healing and reframe mental healthcare. No individual experience was considered valid or another invalid. No individual choice was considered right or another wrong.

Its mission all along, said longtime member and social worker Rachel Levy: “To help people have true, informed consent. To help people know what really is going on in mainstream psychiatry. . . . We’re definitely not about telling you what treatment to pursue, or what decision to make, but we do want people to have accurate information — and we also want people to know that there are other options and alternatives.”

“That was a huge part of the idea,” said Steve McCrea, another longtime member and clinician. “The Rethinking Psychiatry idea, from the beginning, was that it was an educational movement,” he said. “This is an opportunity for people to A) get together and communicate with other people who have similar concerns; B) get to hear the perspectives of people who have actually experienced the system directly; and C) spread some actual data.”

Creating a platform for change

Rethinking Psychiatry was inspired in part by Anatomy of an Epidemic, the 2010 book by Robert Whitaker that examined the long-term effects of psychiatric drugs. He appeared at its first symposium, which was held at Portland’s First Unitarian Universalist Church — known nationally for its work on social justice.

Back in 2008, Meyers was involved with its economic justice (EJ) group when her daughter, Lisa Coppock, was arrested and later roped into the mental health system — or, as Meyers put it, “the mental illness system.”

That’s the short version of the story. The longer version: One day, Coppock had tried to buy a ticket on rapid transit only to discover the machine was broken. She got on the train anyway, money in hand; two stops later, police officers confronted her. When she explained what happened and offered to pay, one of them ordered her to get off. She asked why. Then, sensing his rage, she ran. “He ran after her, threw her to the sidewalk, bashed her head in, and arrested her,” Meyers said.

After 33 times in court, just as Coppock was due to tell her story, the criminal case against her was abruptly dropped. She was shuttled off to her first hospitalization — where, as her mother puts it, she was “incarcerated in the mental-illness system, held down, needle-raped” with drugs including Haldol, Zyprexa, Abilify, and Risperdal.

The dismissal of charges occurred in March of 2010. In May, Portland announced a $1.6 million settlement in a federal wrongful-death lawsuit involving the same cop, Chris Humphreys, and a schizophrenic man, James Chasse, who died of blunt-force injuries after being chased, tackled, beaten, and tased — allegedly for peeing in public.

For Meyers, the connection with economic justice was clear: Chasse’s family had the money to sue. But so many others don’t and can’t, she said. So many others don’t have any support, anyone helping and advocating the way Meyers helps and advocates for Coppock. “It made me realize how many people on the streets there are who were as brutalized by the system as Lisa was — but they didn’t have the resources to do anything except buckle under.” The EJ group at her church agreed. “So that gave me this platform, gave me an arena.”

In the months that followed, Meyers crossed paths with two other women with their own stories to tell: Cindi Fisher, whose son Siddharta was arrested at age 13 for the theft of a coat he didn’t steal, prompting a cascade of traumatic experiences and an ongoing, decades-long ordeal in the psych system; and Grace Silvia, a newly minted social worker with her own story of depression, trauma, and finding a path with meaning.

Fisher described the moment she met Meyers at a Whitaker book event in 2010. “I didn’t know her at all. I just happened to be in the front seat, and she was in the front seat next to me — and she had a daughter in the system, and I had a son.” Siddharta, who experienced his first break at 17, had been struggling in its grips for years already.

The two mothers talked about their children and the need for change. Then they exchanged numbers. “And I got a call from her,” Fisher said, “and it was like, she was serious.”

Silvia, meanwhile, recalled attending a breakfast for FolkTime, an Oregon non-profit providing space and programs for people with lived experience. “And afterwards, this feisty woman starts — as people are leaving — walking through the crowd with purpose, waving flyers.”

The feisty woman was Meyers. Fisher calls her “the fireball behind it all.”

In February, the fireball brought Whitaker back to Portland for “Mad in Oregon,” an event held at First Unitarian and sponsored by an assortment of organizations including the church’s EJ group. A little while later, Rethinking Psychiatry was officially born with plans for a full-blown, two-day symposium jam-packed with programming.

Shortly before its launch, Meyers’ daughter was released from the hospital — a year after she had been involuntarily committed. The move was out of the blue. “And if I hadn’t been there? I mean, this is why people are on the street, right? . . . They traumatize them. They tell them they’re sick, and they push them out the door,” Meyers said. “But they pushed her right into the lap of Rethinking Psychiatry.”

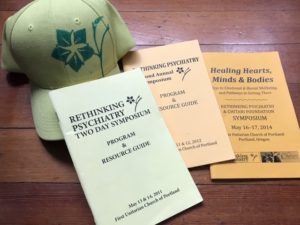

Lisa, an artist, created a cheerful flower logo — still in use to this day — for the sunny yellow hats the volunteers wore. “And they sort of said it all: ‘We’re leading the way, the light is on, wake up.’ And Lisa was there,” Meyers said. “I can’t tell you how moving that was to me.”

So much hope

The program for that first symposium, also dandelion yellow, was more than 60 pages long — crammed with workshops, resource listings, “cafe conversations.” Attendees heard stories of iatrogenic horrors and healing, of medication and peer services, of theories and fallacies and the need for self-care. There were sessions on exercise, acupuncture, comic-book storytelling, cognitive behavioral therapy, Shiatsu massage.

Workshop leaders included Will Hall, who talked about harm reduction in coming off antipsychotics. Donetta Hayes, who described the plight of African-American children on psychotropic drugs. David Oaks of MindFreedom, who talked about activism, peaceful protest, and community organizing.

Fisher, for her part, spoke of her work as founder of M.O.M.S., a movement of parents advocating for their children — and for change.

“It was just so inspiring to hear all these different groups,” she said. Agreed Meyers: “It was so positive. And that’s why I feel like Rethinking Psychiatry gave people an arena to talk about their reality, to feel safe, to not be ashamed. And to share it.”

In those early years, RTP hosted a total of three symposia, all of them held at First Unitarian. The second one, in May of 2012, included workshops on mysticism and madness, on the wisdom of foster children, on nutrition and energy healing and Emotional Freedom Technique. The third one, a May 2014 gathering titled “Healing Hearts, Minds and Bodies,” had sessions on non-drug pathways through depression, on holistic approaches to well-being, on recovery from trauma and the power of laughter.

“There was so much hope — you know, that truly, there is another way,” Fisher said. “And that we had been hoodwinked, to put it lightly. We’d been horribly deceived about what was helping our kids. So I would say that the symposiums gave us enough fuel, enough hope, enough belief, that we could come together for change.”

Over the years, RTP has spread the word and offered platforms for the Reimagining Recovery neurodiversity group. For the Hearing Voices Network. For Peer Respites crisis support. For the Foundation for Excellence in Mental Health Care — now known as OpenExcellence.org — also based in Portland, a key comrade-in-arms in Rethinking Psychiatry’s formative years. It’s one of 20 organizations listed on the resource page, which highlights a diversity of groups that envision and bushwhack alternate paths to wellness.

Its website archives virtually every event ever mounted by the group, old and new, large and small: Scroll down, and you’ll find a November 2019 screening of “Gaslight,” the 1944 film that coined the term now widely used to describe psychological manipulation (free popcorn provided). Asked for other notable events from recent years, Fisher cited a March 2019 event that showcased the Tahoma Sanctuary in Tacoma, Washington, which provides space and nurtures independence for those with lived experience. Another one: a December 2018 appearance by Deborah Schwartzkopff, a survivor of electroconvulsive therapy and founder of ECTJustic.org.

“We were able to bring much more exposure to alternatives and choices — in kind of a centralized place,” Fisher said. “And especially once we got our website, and could continue to share those links.”

Openness to alternatives is the only requirement

All along, a vast chorus of voices have informed and benefited from Rethinking Psychiatry: parent advocates, survivors of the mental health system, concerned providers, more. People arrive in its circle with a diverse multitude of perspectives and their own stories to tell, finding a safe space to expose truths and explore choices. But consensus on issues isn’t a given. It isn’t even an aim.

Because there’s no philosophy or locked-in doctrine, Rethinking Psychiatry is open to all. That openness to all voices, so formative in the group’s creation — “I think that is a strength,” said McCrea, who’s also a comment moderator for MadinAmerica.com.

“One of the critiques of anti-psychiatry is that it can itself become so dogmatic — that a person, for example, who is taking psych drugs of some sort for whatever reason will feel shamed or excluded or criticized. You know, looked down on — because they are still participating in the system in some way,” McCrea said. “And we definitely did not want that message to be getting out at all.”

So if someone finds a psych med or something else helpful for them, McCrea said, “That’s great. You’re not the problem. The problem is the system coming out and telling you that you have depression and that you have to take these drugs, and if you don’t take these drugs, then that’s more proof that you have — what’s that thing they call it? Anosognosia? That you somehow don’t recognize the problem that we all know you have? That’s the problem. The problem is the system labeling, stigmatizing, and, you know, discriminating against people because they happen to feel or think a particular thing.”

And that’s the last thing Rethinking Psychiatry wants to do. “So we’re very open to people from any viewpoint on what is and isn’t helpful.” There are folks on psych meds and folks who aren’t. A person’s credo — whether religious, political, or personal — doesn’t matter. “The main point was for people to be willing to reexamine the model, the basic model. . . . That,” he said, “was the only real criterion for membership.”

That lack of doctrine and radical inclusiveness led to some turmoil when, in 2014, the group was accused of kinship with the Church of Scientology. The flap involved an active Rethinking Psychiatry member “who happened to be a Scientologist” — as McCrea put it, and others agreed — and prompted a breach with First Unitarian. The breach caused a move from its premises; Rethinking Psychiatry then spent five years at an assortment of venues before settling permanently into another Portland church, Montavilla United Methodist.

In response to the accusations, the group posted a “letter of inclusivity” reaffirming its independence and openness:

“We accept no funding or control from, nor do we promote any religion, other organization, government entity, corporation, or drug company. . . . We do not discriminate on the basis of race, sexual orientation, religion or any other group affiliation or identity.”

In the end, McCrea said, the group stayed true to its principles. People often equate any views opposing the pharmacological model with Scientology, using the label to dismissively broad-brush anyone who’s critical of psychiatry. And when they do, he said, he has a response. “If a person says, ‘Are you a Scientologist?’ I say, ‘Why are you talking about religion? I was talking about science. You know, what’s religion got to do with it?”

“Like a lifeline for them”

Everyone has the right to be who they are, say who they are, and be heard as they are: That’s one of Rethinking Psychiatry’s foundational principles, and affirming that has been its quest from the beginning. It was and remains a matter of human rights and justice of all stripes — economic, restorative, social.

“It did have to do with social justice,” Meyers said, reflecting on the group’s founding, her daughter’s story, and the stories of so many in the system. Labeling people as “the other,” as “the problem,” diagnosing and incarcerating them — “I do think people are waking up, now, to this component.”

In a 2015 event, still on YouTube, McCrea talks about ADHD and the too-common, trigger-finger tendency to label and medicate it. He talks about his own son’s toddler years — his nearly constant state of motion, the way he’d barrel ahead on a hike, fall down, get up, and barrel ahead once more.

Then McCrea asks those gathered: “Is there something wrong with him, or is that just who he is?”

On the phone recently, the question was floated back at him. Couldn’t that be asked of anyone? Isn’t it the crux of the conversation — at Rethinking Psychiatry, or anywhere — regarding mental health, the current system, and how to change it?

“It is,” he said. “It is. . . It’s like a battle going on over this question.”

He called it “almost the central issue of this whole psychiatry/anti-psychiatry axis.” At one end, “There’s people who believe that because you’re doing something that society finds difficult, that means that you have a problem and that you need to be fixed.” At the other end, a school of thought that says “it’s up to you to decide whether you think it’s a problem or not. And if you want to do something about it, then my job is to help you figure out what you want to do.”

Ultimately, Rethinking Psychiatry rethinks psychiatry by offering new ways of shaping the narrative, which is currently and overwhelmingly dominated by a mental health system fixated on diagnosis and drugs. Altering that narrative, in both psychiatry and the culture at large, means chipping away at its assumptions and providing information that tells another story: Levy, for one, has seen small, inching advances in the awareness of alternative approaches and how those alternatives are discussed.

“A tiny bit,” she said. “A glacial pace. I think a lot of people are invested in the dominant narrative — I think especially people who have worked in the field a long time.” While the conversation has at least cracked open in the last decade, McCrea said, “There’s still that same kind of disregard for actual facts. To me that’s kind of like the most disturbing thing about the whole field of psychiatry.”

Still, say its longtime members, Rethinking Psychiatry has seen its impact in multiple ways.

One is its success in educating people, in disseminating a wide range of resources. A second is all the conversations held among people of varied backgrounds — including those with lived experience — and the ties formed between groups with similar aims. A third is the sense of community, created over 10 years’ worth of programming and potluck dinners. A fourth is the emergence of hope and shared commitment to change.

A fifth, no less significant, is its effect on individuals in pain.

“Every now and then we would get emails or phone calls from someone in distress, and we would try to refer them onto any resource that we might have,” said Cindi Fisher. There were times when they weren’t sure they could continue, she said. The core circle of volunteers was never large and always working hard. But each time, wondering whether they could press ahead, “We would get an email, or someone would pass the message on, that this was like a lifeline for them — and they hoped we continued.”

Others interviewed made note of this, too. The system itself may be resistant to change, they said, and the narrative itself maintains its stubborn hold. But the people who’ve learned from RTP, who’ve taken inspiration and an alternate approach from it: That’s huge.

“I think we’ve had a lot more impact individually than on the broader society,” Levy said. “I wish we had more impact on the broader society . . . but we definitely had people, over the years, say that it’s helped them to see that another way is possible. We’ve even had a few people say that they think that our group saved their lives — which is amazing to hear. As far as anything broader, I think we’ve at least helped people see that there are other options and alternatives out there.”

Added McCrea: “I think people who were doing alternative things — I think they got a little more energy, a little more acceptance probably, from our support.”

Still making its mark, even during COVID

In the Portland area, Meyers said, Rethinking Psychiatry has indeed left its mark. Within the social system in particular, people are aware of it. When she mentions it, people know what it is. And the need is still there, as RTP and other movements press to acknowledge voices that “the patriarchy” shouts down, she said. There’s no question more people are thinking, and talking, about mental health issues in the context of social and economic justice.

“So the answer is yes. The answer is yes, it’s made a difference,” Meyers said. “And it still is.”

This past year, responding to the pandemic, the group scaled back from its regular monthly meetings and went online — still committed to its founding principles, and still forming connections with other groups on similar missions with similar values. While the turn to virtual was hard locally, “We’re trying to continue building community in COVID,” Levy said. “And the fact that people can learn from other parts of the world has been one of the very few silver linings.”

Grace Silvia agreed. “It’s a trade-off,” she said, “because every single one of us has a deep grief about not doing it in person.” She noted one regular participant, a “brilliant” guy, unhoused, who brought so much to the meetings: “He was a really important part of the in-person community. He doesn’t have a computer and internet. He’s not a part of it anymore.”

At the same time, the move to virtual “opened up possibilities to have speakers not just locally” but nationally and beyond, Silvia said. At one point, making plans for online programming, it hit her: “I said, ‘Ohhhhh, we can have Voyce speaking!”

She means Voyce Hendrix, former clinical director and executive director of the original Soteria House in San Jose, where psychiatrist Loren Mosher first created an alternate, non-hospitalized model of care. “The man is a treasure,” she said of Hendrix, who remains a significant and continuing voice in the efforts to rethink psychiatry. “I called him — talk about chutzpah — and he answered, and we talked for hours.”

Rethinking Psychiatry’s subsequent virtual events with Hendrix include nearly three hours of interviews with him and, just last month, a two-and-a-half-hour webinar devoted to Pathways Vermont, its Soteria House, and the Soteria concept from inception to now. Hendrix, warm and wise, provides the perspective of one who lived and worked in the original house and saw the deeply human credo at play there — “being with versus doing to.” The aim of Soteria, amplified and celebrated in Rethinking Psychiatry’s programming, is to give people a supportive path through challenging episodes without drugging them, hospitalizing them, or dehumanizing them.

In his parting words at the close of the Soteria webinar, Hendrix addresses his hosts: “You guys have captured Soteria. My impression: sort of blown away.” The words used in conversation might be different, using new terms — “peers,” “recovery” — to capture the gist of its mission. “But the essence of it is there. And I’m impressed.”

You can hear someone yell “Whoo-hoo!”

The portrait of Soteria, the affirmation of Rethinking, the recognition of alternate approaches to well-being and recovery — “It was so deeply moving and celebratory,” Fisher said. “It’s like I just wanted to shout YES!”

She said her son is back in the hospital, waiting for discharge — the latest chapter in a long saga with the system that shaped them both. “His path has changed the whole trajectory of my life,” Fisher said. “And it has been incredibly painful, but where I am today, and who I am today: I’m on the exact path that I needed to be. The despair, the rage, the traumatizing that I have felt regarding what was done to him, my hopelessness, my helplessness: It all served to, what?” She paused. “To put me on a path that is full of purpose and passion and hope.”

Evolving organically, for humanity’s sake

Upcoming for Rethinking Psychiatry are many more virtual events, including summits and sessions highlighting peer approaches and the Soteria model in different parts of the world. Next up: that May 23 session on Soteria Alaska. After that, a June 20 presentation on Soteria Israel and a July 11 session on peer-respite houses. Then, down the line, RTP will offer a month-long “Peer Respite / Soteria Summit” with organizers in the US, the UK, Germany, Israel, and beyond.

The Summit will likely be held over the five Sundays in August, probably between 9 a.m. and 12 p.m. Pacific time; other events will run from 10 a.m. to 12 p.m. Silvia urges anyone who’d like to help plan to email the group at [email protected]. She also urges anyone who’s interested in future events to sign up for the newsletter (the red button) at RethinkingPsychiatry.org.

“What is the future for Rethinking? It might be that we do this,” Silvia said. Possibly programming that looks at drug companies. Possibly more on Soteria. Possibly in-person meetings at some point and occasional, real-world events. “Who knows, who knows?” But whatever happens, “It will evolve organically. Hear, hear. And whoever joins the core team — it will evolve based on who shows up. That’s how it’s always been. But I have a huge burst of energy with this,” she said of the latest virtual plans and outreach around the world. “It’s so exciting.”

All of this is affirming for Rethinking Psychiatry’s longtime members, who’ve shouldered the work and navigated the struggles of a grassroots, volunteer-run, radically democratic effort to challenge and change the prevailing approach to mental healthcare.

“The fact that we are still going — I do feel really glad about that,” Levy said.

In a way, that stick-to-it-iveness alone feels like an accomplishment. “I think so. I know a lot of groups have come and gone in this time — and yeah, especially after COVID, a lot of groups kind of fell by the wayside. . . . I mean, it has been tough,” she added. “There’s always other things we could be doing — and you know, there have been things that we haven’t agreed on. But the fact that we are still staying focused on what we do have common ground on? Definitely, I feel good about that. And it does make it worth it when we hear people say how much it has changed their lives.”

For the “fireball” behind its founding, Rethinking Psychiatry remains a cause for gratitude and wonder.

“It’s been six years since I stepped back,” Meyers said. “I can’t say enough about the people that have continued to provide this space.” In the years since, Meyers has spent time volunteering (though not lately, due to COVID) as a teacher in Kenya. She’s living with Lisa, who’s now 40 and pursuing her own path toward healing and transformation.

Via her mother, Coppock was asked if she had any comments on Rethinking Psychiatry.

“I think those who have come together around Rethinking Psychiatry are a brilliant group,” she replied, “as it is so essential to our humanity that we Rethink Psychiatry.’”

And that, said all who were interviewed, takes time.

“The Swahili I’ve learned is polepole, which is ‘slowly, slowly,’” Meyers said. Maybe the paradigm hasn’t yet shifted. Maybe the system hasn’t yet changed. But that doesn’t mean it won’t in the future — and that doesn’t mean people aren’t being empowered right now.

“Yes indeed, we’re getting there, and Rethinking Psychiatry definitely is. . . . And it takes my breath away,” she said. “It takes my breath away.”

Great work, Amy, in profiling this organization for change and the lovely humans behind it all.

Report comment

Yes, this was a very inspiring blog about the important and necessary political efforts organizing against the oppressive Disease/Drug based Medical Model. A noble cause carried out by a very noble group of committed human beings.

Report comment

There’s nothing left to rethink. Psychiatry must go.

Report comment

I am glad that people are actively engaged in the process of “rethinking psychiatry.”

Because some people (hopefully more and more) will end up drawing the same conclusion that I have made over the past decade.

That is: psychiatry (as a medical specialty) should be abolished. It is based on pseudoscience and causes FAR MORE HARM than good in the world.

Richard

Report comment

I agree with this. Many who eventually become antipsychiatry activists begin (like I did) with a “critical psychiatry” stance. There is an evolution of viewpoint that takes place as people gather more information, and I don’t think it’s proper for me to judge where people need to be on that path. I don’t hesitate to lay out facts for people to hear, and I don’t for a minute buy that doing so is somehow “shaming” people who don’t want to know the information. But I don’t expect people to agree with me just because I said so, and I try to meet people where they are and help them take whatever next step seems right for them. Psychiatry takes away people’s ability to make their own decisions about things. I’m not going to do the same, even if people see things differently from me.

However, when we’re talking about systems of oppression, there is no mercy!

Report comment

I agree with this , well said.

Report comment

First, I know of VERY FEW true anti-psychiatry activists who come from the “mental health” or “critical psychiatry” worlds, and their opinions are secondary to the true struggle, which is largely in opposition to the “professional” milieu in which they operate. This is regardless of whether they’re pleasant people to “have a beer with.” Those who respect the concept of survivor self-determination have no problem acknowledging this. And as Steve is indeed one of our very few true “allies” I’ll proceed:

I don’t hesitate to lay out facts for people to hear, and I don’t for a minute buy that doing so is somehow “shaming” people who don’t want to know the information.

This is my essential point. How someone “feels” about the information you give them is largely beyond one’s control. Once presenting such info is construed as “making” someone feel a certain way the conversation is no longer reasonable, but based on emotion. Further

I try to meet people where they are and help them take whatever next step seems right for them.

Which is often nothing at all for the moment. Simply presenting people with the truth is sufficient, if they don’t want to hear it there’s no need to argue. When people are ready to assimilate the information they will; often they’ll come back with more questions.

Anyway I think we all agree that the logical end result of rethinking psychiatry would be to conclude that it should be discarded. Though I think it’s more than a matter of psychiatry being “unscientific”; history is replete with occurrences which were clearly “based on science” but nonetheless evil. Think Hiroshima.

Report comment

Just to clarify, I was not talking only about “critical psychiatry” people from the “professional” ranks. I know of plenty of clients/survivors/victims who totally bought into the “mental health” narrative to start with, then began moving to “Critical” as they learned and experienced more of the failures and damage that the system doles out, and eventually to a more abolitionist stance. Laura Delano is only one good example. I agree it is true that most antipsychiatry activists don’t come from the professional ranks, but “peer workers” and some fringe therapist types (like me) who never did embrace the “medical model” are certainly worth spending time educating. Stephen was another good example of someone who worked in the system but never bought into it, and came to a more radical position through observing the way he was treated in his “peer” role. Such people to me are very much worth educating, as their evolution does happen with some frequency, in my observation.

Of course, I agree that being “scientific” is a necessary but certainly not close to sufficient criterion for any kind of claim of “medical treatment.” And that there are many areas where science is not able to really provide any answers, such as the nature and function of the mind itself.

Additionally, I’m not a pure “professional” type, as you may remember.

Steve

Report comment

Wasn’t addressing my comments primarily to you, except in a positive sense.

However if Laura has “assumed an abolitionist stance,” please tell me more — Laura was probably my singular inspiration for thinking it might be worth getting back into this stuff, but has been pretty remote since starting Inner Compass. I think we may have a political disagreement in that when we last spoke she seemed to think that psychiatry could be “made obsolete” by getting people off drugs and the like; in my view, while valuable, that just gets them back to square one to deal with the same system they started with. But whatever, she might need to keep me and AP at arms length for what she sees as strategic reasons. Not sure.

I don’t remember arguing against education btw, if I did refresh my memory.

Report comment

“One of the critiques of anti-psychiatry is that it can itself become so dogmatic — that a person, for example, who is taking psych drugs of some sort for whatever reason will feel shamed or excluded or criticized.

I’m sorry to see Steve repeating this time-worn (and thread-bare) myth. He should know way better than this by now. I challenge anyone, including Steve, to produce a legitimately anti-psychiatry article or statement which “shames” anyone for taking psychiatric neurotoxins.

Also Steve, if you are going to say that this is a “critique of anti-psychiatry” you should also concede that you see no legitimacy in such a “critique,” unless you do, in which case you should document and defend it. Because people respect you, legitimately, and when you mention such a “critique” you are in effect legitimizing it in many people’s eyes.

Someone “feeling shamed or excluded” is not the same as being shamed or excluded. By saying “for whatever reason” you sort of acknowledge that this feeling cannot be blamed on the anti-psychiatry movement; however it does little to dissuade those who are already prepared to read the “shaming” narrative into anti-psychiatry, for whatever reasons.

Report comment

It’s a legitimate critique of AP activists when dealing in real time with people who aren’t going to come back to keep hearing the message if they feel shamed. And contrary to your personal opinion, feelings fucking matter.

When we are engaging in academic/scientific discussion or debate, our aims are entirely different (or should be) than when we are participating in a real world group where inclusion is paramount. Caring about how people actually feel is more important than telling them what’s wrong with feeling that way.

In my most recent work, I never argue with anyone when they mention their psychiatric diagnoses or drugs. And I don’t engage for very long even here when it is clearly upsetting. Whom would it benefit if they stop hearing me because they feel shamed? Since when has anyone’s feeling changed by being told they shouldn’t feel that way?

You’d do better to save the hostility for those perpetrating the harm and show some compassion to the victims of such. Or at least keep it academic and let those doing the advocacy work on the ground get the message out in a way that is actually accessible to those still in the system.

I have grown, I suppose. I want to convey a message of care and love regardless of where people are at in their journey. I find that more ears open to what I have to say with that approach. I still have my moments of intolerance, where my anger at the harm that’s been done to me clouds my ability to connect with love and compassion to those in front of me. So perhaps you’re having a moment here…

Report comment

I want to reiterate here that when you cause further hurt to someone who is hurting, you aren’t speaking truth to power, you are wielding power. In that case, you have to ask who you are actually serving. Meeting folks where they are at doesn’t mean constant correction until they see things as you do.

When my daughter asked for help paying the copay for her “antidepressant” prescription the other day, I didn’t reply with an admonition that the drugs aren’t good for her or that they aren’t really antidepressants. I asked her how much she needed. She didn’t need an activist in that moment, she needed a mom. Context matters.

Report comment

I don’t see anti-psychiatry as dogmatic. I don’t think there are enough people calling themselves anti-psychiatry to be dogmatic. I see psychiatry as something of an imposition, and, therefore, dogmatic. One is dogmatic for opposing psychiatry? Really? I don’t think so. Anti-psychiatry is a choice. Since when has psychiatry ever allowed freedom of choice. I don’t think they, that is, mental health workers and psychiatrists, are really keen on the idea of “suffering fools”. If they were, then they’d let people be.

Report comment

Frank

I don’t think anyone here has said that an anti-psychiatry stance or an anti-psychiatry political position by itself is “dogmatic.”

Being anti-psychiatry and calling for the elimination of psychiatry as a medical specialty is a legitimate position to take in today’s world. It can be backed up by real scientific analysis, and by an objective assessment of how psychiatry functions as an oppressive institution in society.

I think the point that Steve and KS are making, is that any legitimate political movement or ideology can be incorrectly understood and carried out by veering into a form of “dogmatism.” That is: rigid or mechanical applications of a set of principles or beliefs that ignores context and nuance related to specific circumstances and people.

Richard

Report comment

Thank you for this, Richard.

Frank, I do not believe that the antipsychiatry position is in itself dogmatic. Not at all. I am firmly AP and I take no prisoners when it comes to speaking truth to power – to those are actually in positions of power or privilege. That is also when my writing shines best – when there is fire in my belly, so to speak.

But when I am dealing with people in real time, where I don’t have the luxury of wordsmithing my response, then conveying a compassionate accepting presence is, I find, the most effective way to break down barriers so that they can actually hear the message. If a person feels judged and all you can manage is a retort that they shouldn’t feel that way and give a detailed list of why their perceptions are all wrong, you’re missing an opportunity for connection with that individual because they aren’t going to hear you. Accurate or not, they hear more judgement piled on top of how they already feel. It reinforces what they already think about your position. This is why, as Richard put it, context and nuance related to specific circumstances and people matters.

People change when they feel inspired by seeing a better way. But you have to break down their barriers first. That’s the bottom line.

Report comment

Dear Kindred Spirit,

Knock me over with a feather!

I am astonished at the love pouring out of your comments! I feel drenched in your love.

That is not an obligation to bestow more. You are free to be where ever your mood takes you. I just wanted to honour you.

As for the daughter, put her across your fiercely protective maternal knee and thrash her and send her to her room with no pockey money. The goading button pusher!

(in jest).

Report comment

Wonderful article Amy about brave people. People who no doubt have made a massive difference in lives.

I thought about how if an injury or death were or does occur in a soteria type setting, the media, through nudging from psychiatry jumps on it. Governments swallow the hype, it’s convenient.

Places like Soteria lead to true healing for many, not to chemical lobotomies.

It does not get much better than causing people to think, to think about stuff they have never thought about.

To really examine WHAT it is that they are complacent in allowing by not thinking.

And that is what this is about.

Report comment

What a wonderful community, and especially one that is able to show radical acceptance. I wish we could get something like that going here in Ohio.

Report comment

I’d agree if you changed the title of this article by one little prefix..How about, dot da dah, Grassroots Activism: De-thinking Psychiatry Builds Community? I’m not really keen on any community of abductors, prison warders. and torturers, or of haters in general, even if they’ve got abduction, imprisonment, and torture confused with “mental health care”, or, at least, any sort of “cure” for other examples of confused thoughts.

Report comment

Yo Frank. Don’t hit too close to home.

There’s a basic contradiction here. With the prison abolition movement, those who are objectively the immediate oppressors — i.e the guards and wardens — are pretty clearly identified and identifiable, and there is no pretense that they have your best interests at heart.

Psychiatry is also a branch of the prison system, however Orwell has helped it construe those who are objectively our oppressors — those charged with rearranging our thoughts and behavior to conform to those deemed appropriate — as friends and “peers” who care do care about us and have our best interests at heart. This role confusion lies at the heart of psychiatry’s power, and makes it hard for us to define our political targets. But they’re there.

Report comment

I am not sure if I agree with you as to a comparison between the prison abolition movement– the guards and wardens– and the anti-psychiatry movement having been a prison guard myself. However, from news and reports, it seems that they are now convincing the inmate that the “crimes” that got them into prison were “mental illness-related” and now they must take this pill or engage this type of therapy, etc….Still, I do not see psychiatry as a branch of the prison system. If anything, the prison system may be a branch of psychiatry. Psychiatry at its very base is meant to be evil, although many will deny it. This also includes its child, the study of psychology. Psychology and sociology partially “evolved” from “social Darwinism”—Darwin taken to its worst. Psychology and sociology have been used to “enslave” people in various forms. Psychology and sociology claim they can solve either the the individual’s ills or society’s ills and both would like to cast out God from their midst. I would consider psychology and sociology as branches of Marxism. Prisons existed long before Marx. I think, in time, we may be able to reform prisons. Reforming psychology, psychiatry, sociology, etc. are nothing but a fantasy. Even the Harry Potter book series has more credence. Thank you.

Report comment

Well part of my basic analysis is that psychiatry IS a branch of the prison system, set up to deal with areas of thought and behavior not normally addressed by prisons and judges, though there is also some overlap.

What constitutes “crime” or “evil” is often relative and subjective, the issue is verboten thought and behavior, which varies from culture to culture but is suppressed, partially by psychiatry, across the board.

Report comment

Oldhead, I know we sort of disagree on this. It may really be just a matter of semantics. As bad as the prison system may or not be. This is dependent on country, state, jurisdiction, etc. In my silly opinion, psychiatry, etc. is far, far worse than the prison system. First, in psychiatry you may or may spend time “locked up” in some hospital. And, yes, many times, the “in-patient” is stripped of his or her rights. However, most “psychiatric patients” are treated as “out-patients.” Thus, the “psychiatric patient” thinks he or she is “free” when he or she is not; as opposed to someone locked up in one of the millions of prison systems; where the person knows for at least time he or she is “locked up.” The person in the prison system, depending, on the crime, knows there is the time limit to the incarceration. The “psychiatric patient” is only briefly aware of any time limit and he or she gets further in to the morass and evil pf psychiatry, etc. the whole idea becomes fuzzy until it almost becomes mute. In the prison system, the legalities will usually release the prisoner at the appointed time. In psychiatry, etc. the only person who can release the person is him or herself. I know this gets almost nit-picky. I guess on one wavelength, it could be considered part of the prison system. There are definite overlaps at times, most usually to the detriment of the “patient.” The prison system and in fact the whole legal system do use psychiatry, etc. as a tool or even a weapon against the accused, which, in the end blurs all truth and if any actual justice was done. And, I think, there are those out there who are so dangerous and evil that all fails them or will fail them. But, maybe it is questionable if these people are truly redeemable. But, on the whole, I still believe, by its very nature, psychiatry, etc. itself is so evil that even the prison system, with many flaws, is almost seen as “good.” However, the more the prison and the legal system use psychiatry, etc., they will become part of the psychiatry, etc. rather than the other way around. So, I guess, as things go, I would say that the prison system is part of psychiatry, etc. Thank you.

Report comment

Amy, I thoroughly enjoyed your article. It highlights the tale of a community that does not want to produce something such a bottle rattling production line of organic wine, or bales of colourful knitwear, or gardens of free range chickens, but is a community that wants to build a community. As does Soteria itself. This requires having the integrity to explore fearlessly just what makes a community and what breaks it. I do sometimes wonder what exactly a community is. Is it just a numerical gathering of disparate characters? Or is it a beautiful herd, like antelope, all peacefully grazing in the same approximate direction? Can communities destroy individuals for the sake of the community? Do communities rescue individuals? Endlessly fascinating to ponder this.

And Grace Silvia, it is fantastic to put a name to a face. Your photo looks like you have just dared yourself to keep summoning God and this Divine has blown a honey breeze through your hair.

Report comment

Steve, your photo is full of joyous excitement. I saw your youtube on ADHD and like the way you turn negatives to positives. I can see why you feel diagnosis is a negative and almost seems an act of humiliation. So I can see why you rather a world with no diagnosis.

Report comment

Thank you for your kind words! I’m glad you found the training inspiring. I’m not always full of “joyous excitement,” but I do try to get there at least a few times a day!

Report comment

This is a very interesting article that describes a unique group of people. I have also read these comments with many statements to ponder. I am leery of “social justice” or even “civil rights” as they apply to the “anti-psychiatry” movement, although, at times they do apply. I think there are those who desire to “defund psychiatry” similar to movements across the country that desire to “defund the police.” And, of course, there is the necessity of de-legitimizing what many consider an already illegitimate science, psychiatry. I am really not sure if any of these are the answers to the problem of psychiatry, etc. There is a lot of money here and a lot of people and their families who depend on income from psychiatry, etc. but that doesn’t make psychiatry, etc. moral or legit. I am concerned about politicizing psychiatry, in that this has a tendency to be like the mud that harbors itself in a fan to plaster you against the wall. I do lean towards God as the answer, but, I am no fool, in that many may not, for may reasons, feel comfortable with this position. I did not come to anti-psychiatry through critical psychiatry. I came because I was victimized by the terror and horror of psychiatry, lost a decade or more of my life, and nearly died. I thought psychiatry was the answer as I thought other similar lines of thought were the answer. They were not. However, through the pain, I have learned a lot about who I am, etc. and continue to learn. However, those of us who are survivors of psychiatry’s evil remain hidden, unheard, almost like the lepers of Biblical Times. Yes, we do interact in society, something the Biblical Lepers were not able to do, but, we do so silently, sometimes hiding who we really are and what we really have experienced and know. I have no answers. Yes, we need each other. We need kindness and understanding. And, we also need to be able to tell the world, in this case, you must choose. If you accept your diagnosis; if you accept your treatments, pills, etc. then you have not yet crossed the threshold towards anti-psychiatry. Yes, it is difficult to get off the drugs and the treatment wheel, but you must make some sort of commitment to get off. You must make some sort of commitment for redemption and freedom. The more who do this, the stronger our voices will be. Thank you.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment