When a medical specialty develops its clinical care guidelines, the “experts” in that specialty will review the research literature, and often that evidence base may present a very confusing picture. The results from the studies may be inconsistent, or contradictory. The experts are also faced with the challenge of weighing the benefits of a treatment against its risks. However, there are also instances when the “evidence base” tells a consistent story, across decades and in studies of various types, and when that happens, the experts developing clinical care guidelines can rejoice: science has provided them with a clear picture of what is helpful and what is not.

This provides the clinical context for assessing the importance of Martin Harrow’s latest paper: It adds a new data point to a long list of research findings that all lead to the same conclusion: antipsychotics, over the long term, do not reduce psychotic symptoms, and, in fact, increase the likelihood that such symptoms will persist.

Harrow has now published a number of papers detailing the outcomes of the schizophrenia patients he has followed for more than 20 years. In previous articles, he has reported that those who stopped taking antipsychotic medications did better over the long-term than the medicated patients in every domain: recovery rates, anxiety symptoms, psychotic symptoms, cognitive function, and employment. In his newest paper, Harrow focuses more closely on medication use and psychotic symptoms, and by doing so, he is narrowing psychiatry’s focus to one critical issue: do these drugs provide any long-term benefit?

Antipsychotics, of course, cause many adverse effects, and thus, in any risk-benefit assessment, these drugs need to be effective in reducing psychotic symptoms in order for there to be something on the benefit side of the ledger. If the drugs don’t do that, then there are only risks – i.e. negatives – to be tallied up. And this is why I think we can now say that, with this latest publication of Harrow’s, that the fat lady has sung. The case is closed: psychiatry needs to rethink its use of antipsychotics.

The Evidence Cited for Long-term Use of Antipsychotics

Psychiatry, of course, does have evidence that it can cite supporting long-term use of antipsychotics. Its evidence consists of findings from relapse studies, but, as can be easily shown, those studies do not, in fact, tell of whether the drugs reduce psychotic symptoms over the long-term.

Once Thorazine and other antipsychotics were introduced, researchers ran studies designed like this: They would take a group of patients who had stabilized well on an antipsychotic, and then half of the patients would be withdrawn from the medication, and half would be maintained on it. With great regularity, those abruptly withdrawn from the antipsychotic relapsed at a higher rate. Thus, researchers concluded that staying on an antipsychotic lowers the risk of relapse.

But there are evident flaws in that relapse literature. First, most of the relapse studies involved abrupt withdrawal of the medication, which is known to increase the risk that psychotic symptoms will return. Second, the studies only tell of the return of psychotic symptoms in patients who have been on an antipsychotic; they don’t tell of the risk of relapse in patients who haven’t been exposed to the drugs. Third, they don’t tell of the risk of relapse over longer periods (two years, five years, and so forth.)

Indeed, what the relapse studies prove is this: if a person is stable on an antipsychotic, then it is a very bad idea to withdraw that drug abruptly. They don’t tell of how such treatment affects people over the longer course of their lives.

The Rest of the Evidence

Although it is well-recognized that the relapse studies don’t provide evidence that antipsychotics are effective over the long-term, most in the field assume that that is still true. However, there is a body of evidence, stretching back 50 years, that bears on this question, and when all of it is put together, it tells a consistent story. In brief:

a) In the 1960s, the NIMH conducted a nine-hospital study that compared placebo to drug treatment, and at the end of one year, those initially treated with an antipsychotic had a higher rehospitalization rate. Thus, at this very first moment of the research literature for antipsychotics, there is the hint of a paradox: treatment that is effective over the short term may increase the risk of relapse over the long term.

b) In a retrospective study that compared five-year outcomes for patients treated in 1967 with antipsychotics compared to a similar group of patients treated in 1947 without drugs (as antipsychotics had yet to be introduced), Sanbourne Bockoven found that the 1967 cohort had a higher relapse rate.

c) In three studies funded by the NIMH in the 1970s, which followed patients for one to three years, relapse rates were higher each time for the medicated patients. These findings led the NIMH’s William Carpenter to ask whether antipsychotics induced a biological change that made schizophrenic patients “more vulnerable to future relapse than would be the case in the natural course of the illness.”

d) At that point, two researchers from McGill University, Guy Chouinard and Barry Jones, offered a biological explanation for why the drugs would have this paradoxical long-term effect. Antipsychotics blocked dopamine receptors in the brain, and in compensatory response, the brain increased the density of such receptors. The person’s brain was now supersensitive to dopamine, and this, they wrote, could lead to “psychotic symptoms.”

e) In two cross-cultural studies conducted by the World Health Organization, which compared outcomes in India, Nigeria and Colombia with outcomes in the United States and five other developed countries, the patients in India and Nigeria fared the best. In those two countries, few patients were maintained long-term on antipsychotics, and patients there were much less likely to be psychotic at the end of two and five years.

e) In the 1990s, researchers conducting MRI studies of schizophrenia patients reported that neuroleptic use, at the end of 18 months, was associated with hypertrophy of the thalamus and basal ganglion structures in the brain, and that this enlargement—as University of Pennsylvania investigators reported in 1998 —was in turn “associated with greater severity of both negative and positive symptoms.” Thus, the MRI studies told of antipsychotic-induced changes in the brain that made patients more psychotic over time.

f) In animal studies, researchers at the University of Toronto have reported that the reason antipsychotics “fail” over time, as a treatment for psychotic symptoms, is that they cause an increase in dopamine receptors.

f) A recent randomized study by Lex Wunderink, of the Netherlands, when carefully parsed, tells a similar story. In his study, patients who had stabilized on an antipsychotic were then either maintained on the drug or withdrawn from it (or tapered to a very low dose.) After two years, the relapse rate was higher in the withdrawn/low dose group (43% versus 21%.) However, at the end of seven years, the relapse rate for the withdrawn/low dose group was slightly lower (62% versus 69%), and the key point is this: during those five years (year two to seven in the study), the group that received drug treatment as usual relapsed more frequently than the withdrawn/low-dose group. This is a result consistent with the notion that antipsychotics increase the risk of relapse over the long-term.

g) Finally, we have Harrow’s 20 years’ data. There are two graphics from his newly published paper that neatly summarize his findings.

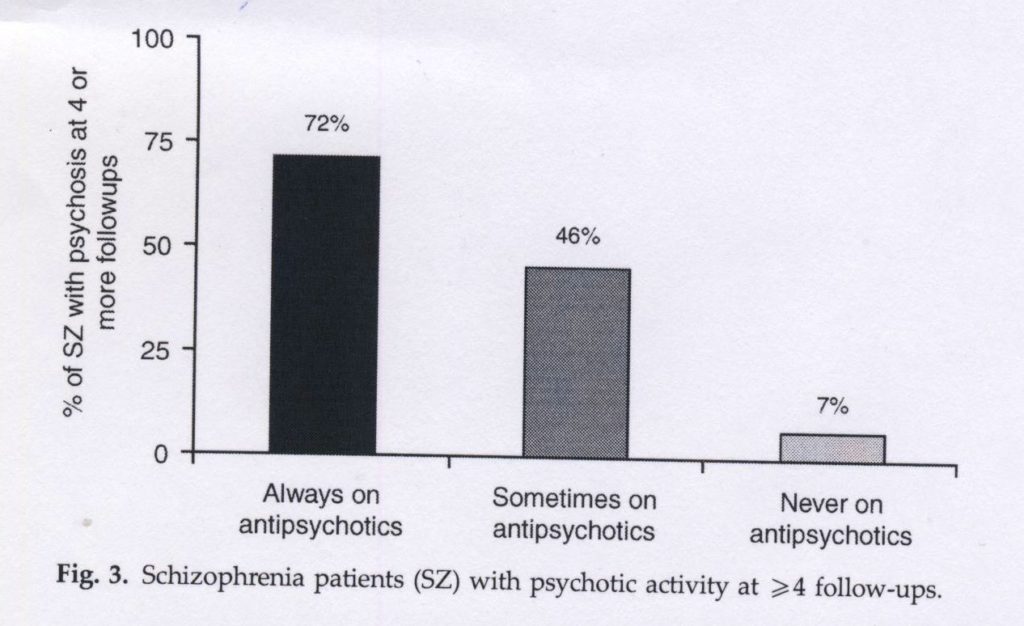

In the first graphic (below), he divides his patients into three groups: those who were always on antipsychotics at the six follow-up assessments; those who sometimes were; and those who were off antipsychotics. He then looks at the percentage of patients in each group who were actively psychotic at four or more of the follow-up assessments:

As can be seen in the graphic, 72% of the medication-compliant patients were persistently psychotic, whereas only 7% of those in the always-off meds group were.

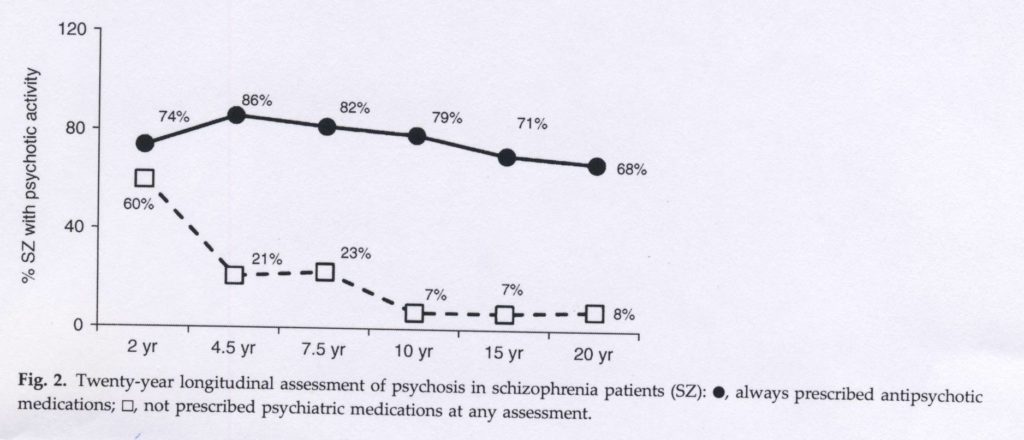

In the second graphic (below), he reports on the presence of psychotic symptoms at each follow-up for those patients who were continually on an antipsychotic versus those who were not on an antipsychotic at any of the assessments.

This graphic shows that at year two, psychotic symptoms were present in the “off-med” group almost as often as in the medicated group. But symptoms then abated in the off-med group, whereas they persisted in the on-med group. This graphic provides compelling evidence that the drugs, at the very least, retard a natural recovery process.

Why the Fat Lady Has Sung

We can see that this body of evidence stretches over 50 years and that it tells a consistent story. The worry that antipsychotics might increase the risk of relapse showed up in the NIMH’s very first one-year study. It showed up in Bockoven’s retrospective study. Next, it showed up in three long-term studies funded by the NIMH in the 1970s. Researchers then offered a biological explanation for why these outcomes were occurring. The WHO’s cross-cultural studies found better outcomes in poor countries where few patients were maintained long-term on antipsychotics. MRI studies identified a drug-induced change in brain morphology that was associated with a worsening of psychotic symptoms. Researchers who developed an animal model of psychosis concluded that drug-induced dopamine supersensitivity leads to treatment failure over time. Wunderink’s randomized study revealed a higher relapse rates between years two and seven for the medicated patients. Finally, Harrow’s long-term study, which is the best such study that has ever been conducted, found that the medicated patients were much more likely to be experiencing psychotic symptoms over the long term.

Harrow’s data does not stand alone. Instead, studies of multiple types are all leading to the same conclusion. Antipsychotics do not reduce psychotic symptoms over the long term and, in fact, increase the likelihood that such symptoms will persist. And imagine if the opposite were true and all these studies showed that medicated patients had fewer psychotic symptoms over the long term. Would anyone then question the long-term efficacy of antipsychotics? Psychiatry would then proclaim that the evidence was overwhelming that the drugs had such positive effect.

In her post on this site, Sandy Steingard presents a very compelling argument for a different use of these drugs: try to avoid initial use if possible, and then, if an antipsychotic is used, see if the person can be subsequently tapered from the medication. And if a person can’t be successfully tapered, prescribe as low a dose as possible. That is a protocol that provides for selective use of the drugs, and there is clearly an “evidence base” supporting a protocol of that type. Indeed, such use could be described as a “best-use” model.

But the obvious question for psychiatry is now this: Can the field as a whole hear the fat lady sing? Or will it turn a deaf ear to her, and continue with care — the regular long-term use of antipsychotics for all — that clearly does harm?

Seems like a fairly open and shut case. Long term use of antipsychotics increases the likelihood for episodes of psychosis to persist. But amazingly we are moving in the opposite direction as evidenced by the latest bill in Congress. So now we have the States and Federal government actively allying themselves with a strategy (long term use of neurleptics) that has essentially been debunked as an ineffective and damaging treatment method.

What will it take to shift the treatment strategy of psych docs? Lawsuits, mainstream media articles, patient outcry, more Thomas Insels speaking louder about this?

The moneyed interests and inertia are strong here.

Report comment

It’s about vested interests and false promotion of mental distress as disease. What happens when anyone takes chemicals to provide peace of mind – in the long-term things get a lot worse.

Report comment

The State and drugs

My own experience with ‘maintenance’ neuroleptics was that they were disabling and more likely to cause mental imbalance problems like suicide.

I became productive on very low doses.

I think that doctors don’t fully understand that the drugs are really tranquillizers, and this because they are too caught up in the ‘illness’ mentality.

Report comment

Great point. I remember when I asked several psychiatrists who wanted to prescribe me antidepressants: “what are these drugs supposed to do to me?” and none of them could answer anything else than “they’ll make you feel better”. “Better how?” was usually followed by silence. I think maybe one of them finally said “well, they make you calmer” to which I responded that I don’t want to feel calm and that’s not the problem. I feel like most of the people described now as mentally ill are actually completely normal, only caught up in certain life situations in which going mad is an escape/survival/defence mechanism. Probably in most cases they can even tell what the problem really comes from. But it’s often easier to give someone a pill than to tackle his/her life problems and certainly easier than to face the fact that some problems have no resolution.

Report comment

I felt so angry and sad when I read this article. My son was started on zyprexa in 2007, at the age of 15! We were told that keeping him on these meds would help him to prevent relapse. What a lie!

In 2012, my son was incredibly sick, and he continued to take his zyprexa, along with some other drugs in his psyche med ” cocktail” faithfully every day. I know this because he insisted that I hand them to him personally. He was so severely affected by terrible OCD that he spent an entire day rocking back and forth in his bed, crying and hitting his head with his fist. We decided to hospitalize him. His therapist recommended he get a ” tune up” for his meds.

After the 2 1/2 weeks of ” treatment” he received, being given a completely new “cocktail”, they sent him back home. He was REALLY, REALLY SICK, and the first day home, he climbed a ladder and threatened to commit suicide. He was so angry and crude that he alienated most of his siblings and family members.

There’s a lot more to this story, but right now, our son is experiencing withdrawal from zyprexa, which he quit taking 9 weeks ago. He’s doing so badly that we considered getting him forcibly put in the hospital a week ago, but the mental health agency suggested we call the police to have him hauled there, and we refused to do that. Instead, we spent hours talking with him until he was calm enough.

I’ve been second-guessing this decision all week, but this article is exactly what I needed to read! I don’t know how long it may take for my son to start recovering, but at least I have the evidence I need to wait it out, if possible. Thank you so much for sharing this information!

Report comment

I Hope we have come to a turning point and all Doctors will hear the fat lady sing. We need to shout it from the rooftops!! Yes Jonathan there will need to be more public outcry, media articles and lawsuits to get the message through.

Report comment

Bob,

Any chance you and your colleagues can influence the results of this horrible draconian law given that it negates all the evidence that you have worked so hard to expose and have accepted by main stream psychiatry to minimize the huge harm of life long neuroleptics:

https://www.madinamerica.com/2014/03/people/

Report comment

Today I sent a note to my representatives with links to Sandra’s story, cepuk, and 1boringoldman. Can’t hurt and for me, it always feel good to take some action.

Report comment

Hi Bob,

Of all of your online lectures that I have listened to, I greatly appreciate the observations you made in your C-SPAN Book Discussion on Anatomy of an Epidemic.

In your talk, you correctly point out that in some cases psychosis can have flu-like characteristics of coming and going on its own.

Unfortunately, when a psychotic state occurs, an individual can become vulnerable. Very often a person experiencing psychosis can loose their ability to manage and maintain personal relationships, employment, medical care, and in some cases, housing.

A psychotic experience distorts an individual’s belief system and perceptions. Many individuals experiencing a psychotic state of mind have poor insight regarding the abrupt change in their mental status and refuse to acknowledge that a problem even exists.

Unlike most other conditions, a psychotic state can cause a person to harm themselves or another.

As the cases of Ryan Ehlis and David Crespi exemplify, a first-time psychotic episode can lead to devastating tragedies that will permanently impact the entire family.

Because there is a legitimate interest in public safety, the state maintains a compelling interest in the treatment of psychotic symptoms.

Yes, the case is closed and the treatment of psychosis deserves strict scrutiny.

Not only do psychiatrists need to rethink how our mental health patients are being treated, our mental health advocates must rethink their advocacy agenda. Advocates from opposing views must work together and create a unified advocacy agenda.

“Advocate” is defined as : a person who publicly supports or recommends a particular cause or policy.

For the past 15 years of my life, I have actively engaged in mental health advocacy.

From what I have observed, our mental health system is suffering because of conflicting research and divided advocacy agendas.

Advocates continue to maintain opposing views from different perspectives and refuse to listen to each other.

When it comes to the treatment of psychosis, mental health advocates should be considering more than just the research, we must consider the facts.

In your book Mad in America, you correctly point out that psychosis various underlying causes of psychosis, including untreated infections in the body such as dental carries.

The facts are psychosis can be caused by a number of underlying medical conditions, or exposure to substances.

If we consider the decision in Wyatt v. Stickney 325 F.Supp. 781 (M.D.Ala. 1971), a key issue was that patients have a “constitutional right to receive such individual treatment as will give each of them a realistic opportunity to be cured or to improve his or her mental condition.”

Our mental health patients under observation for psychosis have the fundamental right to know their diagnosis based on Best Practice Assessment standards.

The “Chinese Menu” approach of using the DSM5 is an unfair and unethical medical practice that seriously jeopardizes the health, safety and welfare of the public.

Psychiatry must move towards adopting Best Practice Assessment Standards and integrative care for their patients as outlined in the British Medical Journal.

All persons who are speaking publicly about the treatment of psychosis are acting in the capacity of a mental health advocate. Mental health advocates have a duty of care to ensure patients suffering from psychosis are assessed and treated under best practice guidelines.

It is negligence on the part of those speaking, lecturing and writing on the treatment of psychosis to ignore the importance of testing for and treating underlying causes.

As a mental health advocate my goals are to advance:

1. awareness of underlying causes of psychosis/mania and the benefit of treating accordingly

2. a Participatory Model of Mental Health Care

3. proactive bullying prevention programs

Please review the BMJ’s Best Practice Assessment of Psychosis guidelines and if you see fit, include discussion of it in the information you provide the public about the treatment of psychotic symptoms.

http://psychoticdisorders.wordpress.com/bmj-best-practice-assessment-of-psychosis/

Kind Regards,

Maria Mangicaro

Report comment

Right on, Maria.

Report comment

Thank u WW for your response.

Somehow, someway, mental health advocates from opposing views must find common ground to stand on.

Advocates should not be spending valuable time and effort seeking ways to defeat one another.

In order to serve the best interest of those they claim to be advocating for, advocates must seek issues that everyone can agree upon.

The common ground issues are the ones that must be brought to the forefront so that our lawmakers can make educated decisions based on a consensual agreement of best-practice, best- interest, presented as a unified advocacy agenda.

Below is the comment I have submitted to our FL Senators.

I am writing in regards to a Doc Fix that includes Section 224 of House bill (HR 4302).

It is my understanding that this action would use federal dollars to pay for forced psychiatric treatment in our communities.

Our mental health care system is seriously flawed in that most medical and mental health professionals use the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM-5) with an opinion-based process they refer to as a “Chinese menu” approach.

This unscientific method leaves individuals suffering from symptoms of psychosis, mania, delusions, paranoia, etc. quickly assessed and labeled with a severe mental illness and treated with a life-long, one-size-fits-all drug therapy regime.

The “Chinese Menu” approach of using the DSM5 is an unfair and unethical medical practice that seriously jeopardizes the health, safety and welfare of not only the patient, but the public at large.

In Wyatt v. Stickney 325 F.Supp. 781 (M.D.Ala. 1971), a federal district court concluded patients have a “constitutional right to receive such individual treatment as will give each of them a realistic opportunity to be cured or to improve his or her mental condition.”

When a psychotic state occurs, an individual can become vulnerable. Very often a person experiencing psychosis can lose their ability to manage and maintain personal relationships, employment, medical care, and in some cases, housing.

A psychotic experience distorts an individual’s belief system and perceptions. Many individuals experiencing a psychotic state of mind have poor insight regarding the abrupt change in their mental status and refuse to acknowledge that a problem even exists.

Unlike most other conditions, a psychotic state can cause a person to harm themselves or another.

Because there is a legitimate interest in public safety, the state maintains a compelling interest in the treatment of psychotic symptoms.

While forced psychiatric treatment may be deemed necessary, if federal tax dollars are providing the treatment, strict scrutiny must be used. The state must ensure a patient’s fundamental right to receive individual treatment is preserved and best practice assessment standards are available.

Diagnostic accuracy and individualized treatment of psychosis is cost-effective for both the mental health consumer and society.

The British Medical Journal has published guidelines for Best Practice Assessment of Psychosis.

Over 100 medical conditions and a long list of substances can induce a psychotic/manic state, which can lead to a misdiagnosis of severe mental illness.

From what I have observed, our mental health system is suffering because of conflicting research and divided advocacy agendas.

Advocates continue to maintain opposing views from different perspectives and refuse to listen to each other.

When it comes to the treatment of psychosis, mental health advocates need to consider more than just conflicting research, we must consider the facts.

The facts are psychosis can be caused by a wide variety of underlying medical conditions, or exposure to substances and patients are being rubber-stamped with mental illness labels.

Typically, psychiatric treatment fails to test for and treat underlying causes of psychosis.

In many cases, patients are placed at risk and because of the legalization of coercive treatment, the patients are responsible to pay for the treatment they received.

Patients not only continue to suffer unnecessarily, they received outrageous bills for treatment that failed to consider the underlying cause of their symptoms.

These bills should be considered illegal forced contracts of goods, services and accommodations.

If federal dollars are used to pay for forced treatment, patients must be ensured their fundamental right to receive assessment and treatment according to best practice standards is preserved.

Report comment

Did I get it right that the involuntarily treated patients have to PAY for their treatment? Talk to me about insanity…

Report comment

Hi B,

I would love to talk to you about insanity.

I wish I could say April Fool’s Day, but yes, in most stated, for psych patients, forced to stay and forced to pay is the law.

Coercive psychiatry is a unique situation in which our lawmakers have created a system which allows legal forced contracts between mental health patients and providers/facilities.

And also, unlike any other bad product, there is a no refund policy at the drug store for bad pharmaceutical products that induce side effects that can kill you.

I’ve thrown away prescriptions that cost me out-of-pocket up to $250 because I could not tolerate the side-effects.

Many psych patients can’t afford tp purchase food, but they can get plenty of lethal medications paid for by their insurance.

Adderall has become a very popular medication to obtain and sell, as taking stimulants affects the metabolism of alcohol in the body. As a result we are seeing increases in DUI accidents/related deaths.

Mental health advocates with opposing views will argue with each other about what type of treatment “psychotic” patients should receive, but they don’t seem to care about getting them food to eat.

And also, psychiatrists will order lab-work/tests to run up the patients bill and then never even review the results, or give them to the patient.

I recommend to all psychiatric patients that they obtain their medical records and lab work from all of their doctors.

It’s no mystery to me why on average our “mentally ill” are living 25 years less than our mentally healthy population. Yet, no one really seems to care about helping them receive proper medical and dental treatment.

My own situation involves an occupational disease that manifested as an acute manic episode. Long-term chemical exposure in the work environment caused toxic encephalopathy (Multiple Chemical Sensitivities).

I was misdiagnosed with manic-depression with psychotic features and it took several years before I found help through alternatives/Functional Medicine.

As Bob correctly points out, psychosis can have flu-like characteristics of coming and going on its own.

The reason why symptoms of psychosis can sometimes come and go is because there are a multitude of underlying conditions, such as food allergies, or undetected infections, that exacerbate symptoms, even many years after recovery.

Here is a copy of a +$8000 bill that I received after an abscessed tooth exacerbated symptoms of psychosis and I was forcibly treated for psychotic symptoms.

I filed a complaint with the facility that this was an illegal forced contract that deprived me of my fundamental right to receive necessary medical treatment for an abscessed tooth.

They dropped the bill completely.

The facility I was “treated”, along with NAMI, would run an ad in the Sunday paper showing a baby behind bars, stating children with “untreated” “mental illness” end up in jail.

Nice advertisement for bad “treatment”.

Another facility I was “treated” at ran an EKG that showed possible anterior infraction. My doctor never even looked at the results and I was never informed there was a problem.

Nice of them to administer drug therapy for “mental illness” and ignore physical illness.

The treatment of psychotic symptoms is boiling down to a battle between Medication Management v. Open Dialogue, while failing to address treatable underlying conditions.

Albert Einstein defined Insanity as: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

Mental Health Care = Insanity in America

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1HGhDuHaojrVnYGaipMnJ6PAEVSCMdWpZK_5zLd42Xyo/edit?usp=sharing

Kind Regards,

Maria

Report comment

Chinese menu and DSM

You can find the DSM in anyone if you try hard enough, or ask enough leading questions. Its the longterm tranquillizer treatment approach that turns the diagnosis into reality.

For someone with emotional problems that come to a head the solution has to be in the Psychological process, or else the problems remain. Once the problems get dealt with, a person can get back to the same normal life as everyone else.

Report comment

Hi Fiachra,

Here is an article from Psychiatric Times “Catching the Right Fish”.

http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/dsm-5-0/catching-right-fish

As Dr. Thomas Szasz tried to explain, the concept of “mental illness” is something our society has bought hook, line and sinker.

Report comment

Thanks for the cogent summary connectING the dots psychiatry fervently wishes not to connect. I would add another dot:

The WHO’s final report on its international schizophrenia longitudinal studies puts an exclamation on its earlier 5 year studies. “Recovery from Schizophrenia,” (2007) reports another follow up that showed the WHO’s prior findings held up after 25 years. If anything, the developing countries’ advantages were even more unavoidable.

Here is the report on the Agra, India center patients: “ Forty-five (73.8%) of the 61 cases alive at the 25-year follow-up had been in complete remission at the initial 2-year follow-up, and 77% were currently asymptomatic.” (p. 80).

Moreover, “In the last 2 years of follow-up, 72.7% of the Agra cases never used neuroleptic medication.” (p. 82). The authors give an understated nod to the implications of the connection between high recovery and low drug use: “… the fact that recovery rates were so high suggests a much lower need for maintenance medication.” (p. 82)

However, the authors minimize the fact that the study center with the lowest neuroleptic use had by far the best outcomes. They conclude: “In spite of the fact that use of neuroleptics is uncommon and hospitalization is not the usual treatment choice, global outcomes in the final 2 years of follow-up was noted as much better. Examining various variables yielded no relationship that could be specifically related to outcome beside family care. It is therefore surmised that schizophrenia runs a natural course, and the longer the survival, the better the outcome.” (p. 84)

The chapter on the 25-year follow up at the Cali, Colombia center similarly noted “the short duration and the small number of hospitalizations as well as the sporadic use of treatment,” concluding, “Such evidence suggests the existence of a disease process less malignant than the one usually attributed to schizophrenia. Similar findings in several contemporary studies indicate the need for a change of paradigm – namely, the notion that schizophrenia inevitably evolves toward chronicity and deterioration should definitely be eradicated.” (p. 98)

The book’s concluding chapter: “Consistent with the earlier findings … course and outcome for subjects in the developing centers were more favorable than for their developed world counterparts. Most of the difference registers early on, in the initial two years of illness …. But even for subjects whose early course was poor, the likelihood of later recovery favors those in the developing centers (42 vs. 33%).” (p. 178).

But in an apparent effort not to be drummed out of the psychiatry club, and to avoid having their conclusions ignored altogether, the authors’ conclusion chapter doesn’t breathe a word about freedom from neuroleptics affecting developing nations’ good outcomes. They focus instead on culture and family.

Report comment

They also have very good outcomes in Finland with the use of Open Dialogue approach, which concentrates on the societal and psychological intervention rather than drugs in the first episode psychosis cases. They have also observed the correlation between use of antipsychotic meds and worse outcome.

Report comment

Hi Peter

I don’t think there’s any mental health false economy in India, and its not in their interest to invent one – the disability comes from the treatment.

Without the treatment the forced medicating is not an issue either.

Report comment

Robert Whitaker I think you have a typo of two ” f )” categories.

If psychiatrists are in fact doctors, the news ( of long term outcomes) should be widely distributed.

Hand washing before childbirth took years to be accepted, and ulcer-causing helicobacter pylori took twenty years to be accepted.

Report comment

I wonder what effect the long-term use of anti-psychotics as an addition to an anti-depressant for the treatment of depression will be.

Report comment

Talk about the double whammy! I have friends who were told by psychiatrists that they needed to take Abilify in addition to their antidepressant because the Abilify jump starts the antidepressant and makes it work sooner and better! What a huge pile of bull feces! And yet people swallow this hook, line, and sinker! I would have thought that everyone by now knows that antidepressants work no better than placebo and can end up causing depression and suicidal and homicidal tendencies. Is everyone in this country standing around with their heads in the sandk?!!!

Report comment

True, I was also offered Ability for depression and the psychiatrist got very confused when I asked why the heck is he giving me an anti-psychotic. Apparently that was to treat my anxiety symptoms which come with depression. I have a feeling that as soon as you have one problem and they start you on drugs then you tend to develop other problems (I’ve heard some call it unmasking;P ). Depression -> SSRI -> anxiety -> Abilify -> aggression/psychosis -> hospital, more drugs in higher doses -> life time zombie

Report comment

What they call “unmasking” is actually the detremental effects of the drug causing harm to people, but you obviously understand this because of how you end your response. People need to wake up and quit listening to all this horse manure that psychiatry and the drug companies are putting over on us.

Report comment

What about Ketamine. Is this a cry for help?

Report comment

I believe that Big Pharma holds the power, here, dangling drugs as though they were candied colored panacea. Psychiatry is merely a pawn in their game, and they’re not exactly doing very good PR work for them. Society, as a whole, has never really regarded psychiatry very highly, and now, psychiatrists are alienating those that have come to them for support, big time, with their overt and covert betrayal to the cause of health and well-being. People have been waking up to this for a long time, and at present, that particular choir of voices is getting louder and stronger.

But it is still Big Pharma that is calling the shots given that it is their $$$ which talks loudest in that world. They seem to have a lot of support from other powers that be. Even if people go off psych meds in droves, then that will only serve to increase the power of other medical-phrama alliances, as psychiatry will no longer be useful to them, and would only serve as a liability to their mission of profit, rather than as an asset to it.

My curiosity is focused on which domino will be the first one to fall, that will knock down all the others in order to, once and for all, break up this incredibly lousy and socially betraying system of bad “medicine.”

Report comment

I think they are partners Alex, and they’ve gotten so greedy that they’ve been found out. Now, after 30 years of tranquillizer medicine most ‘psychiatrists’ are not qualified at anything else, so they have nowhere to go.

Report comment

I agree that psychiatry has painted itself into a corner, as they have failed to adequately address issues, while insisting that they are doing ‘the best they can.’

While perhaps they have done the best they can with what THEY know, what they know is not nearly all there is to know about the mind, heart and spirit, which other healers DO know. Of course, these other healers to which I refer don’t have political or financial clout, and sadly, that makes all the difference in whom we ‘trust.’

Individuals seeking support for mental distress and other manifestations of the psyche now have opportunities to seek support from other, more knowledgeable sources, with more effective ways of addressing issues of mind, body and spirit. It is up to each person to find what works best for them. There are solutions to these issues, which are not always terribly complicated, whereas psychiatry insists that people are ‘limited.’ Not all healers believe in these limitations, nor in anything chronic. This is part of awakening to the truth about ourselves, and of how society operates.

Big Pharma, on the other hand, can tap any medical branch to sell their product, so that will take longer to dissipate. Nature tends to contain remedies for everything and anything, but, on the whole, we have become accustomed to chemicals, which go against nature. The powers that be–from greed, as you say–run a brilliant PR campaign that has convinced people they need these chemicals, and now millions are addicted, not just to the chemicals, but also to the thought and idea that they need these chems. So people pay out the nose for them or rely on the government to do so, on their behalf, creating yet another dependency) and not only is nothing remedied, things tend to get worse and conditions become unnecessarily chronic. It’s a tragic hamster wheel, until people wake up to the fact that they’re being lied to, and until they can learn to, once again, trust nature and the natural course of energy.

Report comment

Hi Alex

Maybe doctors have to cooperate with the way things are done and can only express themselves when they get into authority, but at the same time lots of established doctors must be aware that the medical approach is barmy.

Any time I see a newspaper over here there’s a new wonder drug discovered. Not for mental illness though, I think they have already moved from this, and the patents are running out as well.

Report comment

“Maybe doctors have to cooperate with the way things are done and can only express themselves when they get into authority”

To me, that would speak of the hierarchy that defines and runs our systems, which I believe is one of the things that has caused so much confusion and so many problems. These hierarchies are illusory, as it is often based on deceit and misrepresentation, and are based on nothing more than aggressive power, not at all indicative of who really knows what and who is qualified to heal and coordinate, but more about who is most cleverly manipulative and pushy.

Only expressing one’s self when in authority is kind of cowardly, don’t you think? Those are the ones who actually have authority issues which cloud neutrality and objectivity–i.e., false sense of self and personal power. Their power is based on their ability to control others by exploiting peoples’ vulnerability, fear, and desperation. That’s how I see it, in any event.

“Any time I see a newspaper over here there’s a new wonder drug discovered. Not for mental illness though, I think they have already moved from this, and the patents are running out as well.”

Well, that’s a start, at least! One day, we’ll realize that there is no such thing as a ‘wonder drug,’ other than on an individual basis. Different things work for different people. We’re all different and respond differently to different things. I don’t see how anything else could be true.

Report comment

Well, except maybe for oxygen, water, nature in general. These seems to work miraculously for an awful lot of people!

Report comment

“Mental illness” is the camel’s nose. But rackets are such an America thing. It is another symptom of why America is now stuck in a cul de sac. Beyond a certain point the pursuit of wealth fails a society. We are at the stage of falsehoods now. How long this can last I do not know. I am still wondering why Obama’s speech writers would put a big fat juicy lie in his speech in Belgium to an elite European audience, namely, the Kosovo referendum. Maybe the speech writers are as illiterate and ahistorical as he is. In any case the view from the cul de sac is very limited. Psychiatry is largely a fraudulent profession which has done a great deal of harm. I can not recall a single film in which a psychiatrist appears where he/she is not presented as an evil element. And for years I used to see a bus around town that had “Psychiatry Kills” painted on the side. So true.

Report comment

Very much like global warming! The greed is on one side of the argument and the legitimate science is on the other side…

Report comment

You all got to see the film Ward No. 6 based on a short story written by Anton Chekhov about a director of a mental hospital in Russia that becomes an inmate of that same hospital.I found it streaming on Netflix just enter Ward No. 6 in the search box.

I wish there was a deeper understanding within all people of the more natural healing systems ,energy healing systems like YuenMethod, also Traditional Naturopathy and Homeopathy among others. Health is a natural progression from these modalities.Also Hal Huggins protocol dentistry is much more important than most everyone realizes. Investigate Paracelsus Klinic (google it).

Report comment

Hi Bob, forgive me for not having read the recent Harrow article in full, or I might have already figured this out, but here is the question I worry will come up if I try to cite the article as being definitive:

I am imagining that people who believe more in “antipsychotics” will say that probably what happened was that those who were having better outcomes anyway tended to get off drugs successfully (while those who tended not to be having better outcomes might have tried to get off drugs but usually got put right back on them after they did poorly off them.) Also, they might ask if the people who were off drugs 10 or 20 years later were really all the same people as those who were off drugs at 2 years, or was it the case that some of those off drugs at 2 years went downhill and got put on drugs, while some of those on drugs at 2 years did relatively well and got off drugs – so that over time, there was a filtering so that those who tended to be doing better for whatever reason showed up in the “off drugs” category.

In other words, they will say that it isn’t that drugs worsen outcomes, but those with worse outcomes tend to be the ones that end up on drugs over the long term.

Is there a way we can prove that this explanation can’t be correct? If we can’t disprove that explanation, then the “fat lady” will have to hold off her singing for a bit longer, much as we might wish to hear her voice.

Report comment

Hi Ron

I was diagnosed Acutely Schizophrenic in 1980, Chronically Schizophrenic in 1984, and then Schizo affective with poor prognosis. I quit depot medication in 1984 through a slow taper with oral medication.

I became fit for work as a result of this, and moved back into normal employment and independence. I have remained well since with the help of Psychotherapy. This is where the answers were for me.

The real disability was due to drug induced movement disorder.

Report comment

Which came first the chicken or the egg? Who is paying for all this sh@t?

Report comment

I think that most people are not genuinely ‘Schizophrenic’ to begin with, but being in the system turns them into mental cases. The value of Psychotherapy is that it can put everything right again, even the mental imbalance caused by the drugs.

Report comment

Okay , you go to the thief that robbed you to get un-stolen, you go to the thug to get un-beaten, you go to the drug dealer to get un-drugged. RIGHTtttt.

Report comment

Hi markps2

The Psychotherapy was totally outside of Psychiatry. It was what I asked for at the beginning, and it worked for me.

As far as thieves and thugs and drug dealers are concerned I would do as much as I legally can to expose them.

Report comment

Fiachra , it is a good thing you found healing.

Report comment

Hi Ron,

I’m not sure what conclusions to make of this study. But in any way, in this paper Harrow divided the patients to three groups: those who ate neuroleptics all the time, those who at times ate neuroleptics and those who never ate neuroleptics (possibly seemingly). For instance, in that second graph, it seems it includes patients only from the first and third group, that is, those who took neuroleptics all the time and those who didn’t ever take it, maybe from the two year point. It still seems possible that people from first and third group jumped to the second group, that is, the group who sometimes used neuroleptics. Etc.

I don’t see it’s any kind of a definite proof that neuroleptics make it worse in long term for every person with the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Often we haven’t even very clearly even defined what “better” or “worse” even mean, except through some psychologic tests.

However, let’s begin with this: it’s common “wisdom” among psychiatrists and lay-people alike that “schizophrenia” is a single brain-degrading cellular level brain disease alike to Parkinson’s (often only reverse in the dopamine function), and that psychologists or psychiatrists can reliably determine its presence with their tests, etc, and often that perhaps only drugs can prevent that degration, and drugs should be given to every “schizophrenic”. This is a very common view of what “schizophrenia” “is”. By the law of contradiction, Harrow’s studies at least show this view of “schizophrenia” is not right. There’s something wrong in there somewhere, probably in many places.

Report comment

Hi Hermes, I can definitely see how to argue for all the conclusions you have made, especially about the study showing there is something wrong with the conventional view of “schizophrenia.” But I know Whitaker was trying to go further than that with it, and I still have unanswered questions about that.

Report comment

I am also concerned about this weakness in the argument. It would seem that a person’s probability of initially being placed on medication is higher if their symptoms are more intense. That would mean the people not on medication are those who had the least severe symptoms to begin with and thus were more likely to recover anyway.

Report comment

It’s interesting to think… even assuming these chronic illnesses do exist as they are reported to (I feel dirty) might this data show that if they are not used sparingly their effectiveness is reduced ?

Like a Parkinsons patient with l-dopa ?

Report comment

barrab,

Does any tranquillizer work in the long-term? Alcohol is brilliant for social anxiety, but in the long run an alcohol reliant person can get very paranoid. When an alcoholic stops drinking he joins a group not just to stay off the alcohol, but to remain sane.

Report comment

You are definitely right about careful use, if this was done there would be no serious problem to begin with!

Report comment

To Maria:

“Coercive psychiatry is a unique situation in which our lawmakers have created a system which allows legal forced contracts between mental health patients and providers/facilities. ”

Can’t that be challenged in courts? I mean it has to be in conflict with some basic protections…

Report comment

Hi B,

While the use of coercion in psychiatry stirs a lot of controversy among advocates, no one really seems to care about who gets stuck with the bill.

Coercive psychiatry means a mental health patient is forced to contract and purchase products, services and accommodations without choices or alternative options.

The contractual relationship between a psychiatrist ordered to treat a patient, as well as the contract between a facility detaining a forcibly treated patient, should be challenged in court.

In the U.S., “liberty of contract” is implicit in the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Under forced treatment laws, mental health patients are deprived liberty to contract.

Report comment

So in theory you could challenge this in courts for being unconstitutional in a class action lawsuit?

Report comment

Looking at the paper, the conclusions section from the executive summary seems to warn against making the sort of strong claim that Whitaker does in this post:

“The 20-year data indicate that, longitudinally, after the first few years, antipsychotic medications do not eliminate or reduce the frequency of psychosis in schizophrenia, or reduce the severity of post-acute psychosis, although it is difficult to reach unambiguous conclusions about the efficacy of treatment in purely naturalistic or observational research. Longitudinally, on the basis of their psychotic activity and the disruption of functioning, the condition of the majority of SZ prescribed antipsychotics for multiple years would raise questions as to how many of them are truly in remission.”

The paper seems to provide evidence that is consistent with the claim that antipsychotics impede recovery from psychosis, but it also does not demonstrate that that claim is in fact the case.

Report comment

“Influence of prognostic factors. We also analyzed prognostic factors that may influence SZ outcome, controlling for prognostic factors (Vaillant, 1978) and pre-morbid developmental achievements (Zigler & Glick, 2001). SZ continuously prescribed antipsychotics had significantly poorer developmental scores on the Zigler scale (t=2.09, df=36, p<0.05). However, when controlling for this by comparing SZ from each group who had poor prognosis scores on both prognostic indices, SZ continually prescribed antipsychotics had significantly more frequent periods of psychotic activity than SZ continuously not on antipsychotics (χ2=4.11, df=1, p<0.05). "

from the paper. In other words: when they controlled for prognostic factors data had the same trend. Of course there may be some factors that were not reported that led to difference in treatment but from the evidence available it still stands.

Report comment

There are a lot of good points here. A couple of notes.

a) As for the Harrow study, this latest study is one of many he has written reporting his outcomes. As B (above) notes in his comment above, Harrow looked at different prognostic factors, and concluded that controlling for them, he still found more psychotic symptoms in the continually medicated patients. Moreover, and this is key, it isn’t that the off-med group at year two is doing much better than the medicated patients on psychotic symptoms, they are roughly the same. What happens is that the off med group, which is doing little better than the medicated group at year two, gets much better from year 2 to 4.5. You are seeing a healing process there off meds that you don’t see in the continually medicated group. Furthermore, if you look at his earlier studies, he found better outcomes in every subset of patients (grouped by prognostic factors) in the patients who were off neuroleptics. So his study, standing alone, is one data point, and it says this: over the long-term those taking neuroleptics were much more likely to have persistent psychotic symptoms.

b) Second, the point I was trying to make in this post is that the Harrow data doesn’t stand alone. It is a data point in a long line of data points, which tell a consistent story. The hypothesis that the drugs cause a dopamine supersensitivity that increases biological vulnerability to psychosis arose thirty-five years ago (in response to other clinical studies,), and the Harrow data is consistent with that theory. That is the point. It is all telling the same story, and that is where this conclusion comes from: the pieces of the puzzle fit together.

c) As for the WHO studies, that is another data point, and yes, as noted above, the 15-to-20 year data are quite compelling, showing better long-term outcomes in places where people weren’t regularly maintained on neuroleptics.

d) Finally, in terms of the burden of proof, remember it is the responsibility of those doing a medical intervention to show that it is efficacious. It isn’t enough to simply criticize the many, many studies that tell of worse outcomes associated with continual neuroleptic use; the providers need to point to studies that show the drugs improve long-term outcomes. They admit they have no such studies. So what you have here is this: a consistent body of studies, of many times, stretching across 50 years that tell of drugs that impair long-term recovery, and even increase psychotic symptoms. You don’t have any that show the opposite.

And that is why I think we can fairly say that the fat lady has sung on this topic.

Report comment

Hi Bob, While the fat lady sang for me a very long time ago on the question of whether long term antipsychotic drug use is generally a good idea, and while I think it is clear that the preponderance of the evidence is pointing to long term antipsychotic treatment being overall detrimental for most people, I still wonder if I could convince a more skeptical person that this latest study carries much weight of itself.

The question I raised earlier was whether it could be reasonable hypothesized that the people who tended to incline toward long term problems anyway got quickly put back on drugs when they tried to quit, while others who were inclined toward recovery managed to stay off drugs when they quit them, resulting in the use of drugs being just correlated with worse psychosis rather than causing it.

I don’t think the bit about prognostic factors really answers that question, because one might expect that within the group with better prognostic factors, some would still be individually inclined toward more long lasting psychosis (within group variation), and some not so much, and if those individually inclined toward more long lasting psychosis then got steered more toward staying on drugs, then you would get a result much like Harrow got, but it wouldn’t be due to the drugs causing the problem.

If I knew that the group being off meds at 4.5 years consisted of the same people as those off meds at 2 years, then I think the case for the drugs being detrimental would be strong as you suggest. But if the group off meds at 4.5 years consists partly of people who were off meds at 2 years, and partly of those who were on meds at 2 years but who tended to be doing better and so managed to safely get off by the 4.5 mark, while those who were in the medicated group at 4.5 years consists partly of those who were medicated at 2 years, but also partly of those who were not medicated at 2 years but then relapsed and got put back on medications, then the meaning of the better results at 4.5 years might be very different – if might mean perhaps just a tendency for those who tended to do poorly to end up on drugs, with that being much better sorted out at 4.5 years than at 2 years.

So I agree with you there are lots of other reasons to think that the drugs do increase problems for people in the long run, but unless I’m missing something, I don’t think I could put the kind of weight on this study that I could on something like the Wunderink study, where it is hard to argue that it was anything other than the reduced medication that led to the better functional outcomes. (In that study the group on less or no medication didn’t have less psychotic symptoms, they just were more than twice as likely to recover in other ways – which might also lead people to questioning if the drugs really do increase psychotic experiences in the long term.)

Anyway, I’d be happy to hear about any holes in my reasoning, I’m just trying to sort this out in my own mind, so I can be sure of where I’m coming from when I communicate with possible hostile audiences.

Report comment

You’re of course right that is hard to prove causation from this particular study but the point is: it’s not the only one. I think for me the most telling one is actually the WHO study since there you’re unlikely to see a difference between the groups on meds and not on meds due to differences in symptoms severity: in some countries you simply don’t use as many drugs as in the developed world. Still you see the same trend. I think that in fact “Finally, in terms of the burden of proof, remember it is the responsibility of those doing a medical intervention to show that it is efficacious.” is the most compelling argument. If people who are not put on drugs do well without them and people who are on them don’t do well anyway then what’s the point? Even assuming that the people in the on-meds group were really more severe cases then anyway most of them still have no benefit. Given the serious side effects of these drugs it’s a valid question if they should be used at all. I think the only way to have a direct answer would be to do a controlled long-term study with drug vs placebo but I assume that isn’t really possible due to a number of factors. However, the data seems to be good enough for me to at least say that the drugs should be the last resort and only given if other alternative approaches fail.

Report comment

Hi B, Before the drugs came, and back before the asylums were invented, people still went mad but they didn’t get diagnosed as Schizophrenic or Bi polar. Most people recovered. You didn’t have a situation like what you have today with long term disability affecting 2 to 3 percent of the country.

The Asylums were supposed to be helpful places, and then they became an industry, and open to abuse.

Myself, I would have needed some kind of psychotherapy to remain recovered. This is available to me in the community though (through the 12 step and other recovery groups).

Report comment

Thanks a lot for your further thoughts, Robert. I feel persuaded after seeing the Harrow study in the context of the others. The Harrow study is observational and thus difficult/impossible to draw causal conclusions from, but randomized experiments appropriate for drawing such causal conclusions have found the same thing, thus a larger picture is being drawn wherein a fat lady can be seen singing 🙂

Report comment

The psychiatric drugs are to control people, not to medically help them.

It is obvious from the start. There is no psychotic molecule, virus or bacteria.

The drugs help in that they help the patient obey orders. That is all.

[ If a patient is poor he is committed to a public hospital as a “psychotic.” If he can afford a sanitarium, the diagnosis is “neurasthenia.” If he is wealthy enough to be in his own home under the constant watch of nurses and physicians, he is simply “an indisposed eccentric.”] Pierre Janet (1859-1947)

Report comment

http://www.straightdope.com/columns/read/748/whats-the-origin-of-the-opera-aint-over-till-the-fat-lady-sings

Report comment