I presented the following comparison of the philosophic psychiatry of Thomas Szasz to the psychiatric philosophy of Epicurus in May 2014 at the 167th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in New York City. Because Szasz had died late in 2012 I assumed it would be merely one of several retrospectives of his thought and influence. In the event, mine was the only paper to mention him, and the circumstances afforded me for presenting it proved challenging. I was assigned to the last slot on the last of the five-day conference, to a session titled “Topics of Interest Rarely Presented.” (The first presentation discussed psychiatric patients’ self-assessments of body weight, while the third dealt with psychiatric morbidity among Bangladeshi women in rural and slum populations.) The audience was predictably small, but the paper was quite a hit among them. It has continued to garner favorable remarks in private circulation. Since the second anniversary of Szasz’ death on September 8 is now approaching, it seems a suitable occasion to publish it to a wider audience.

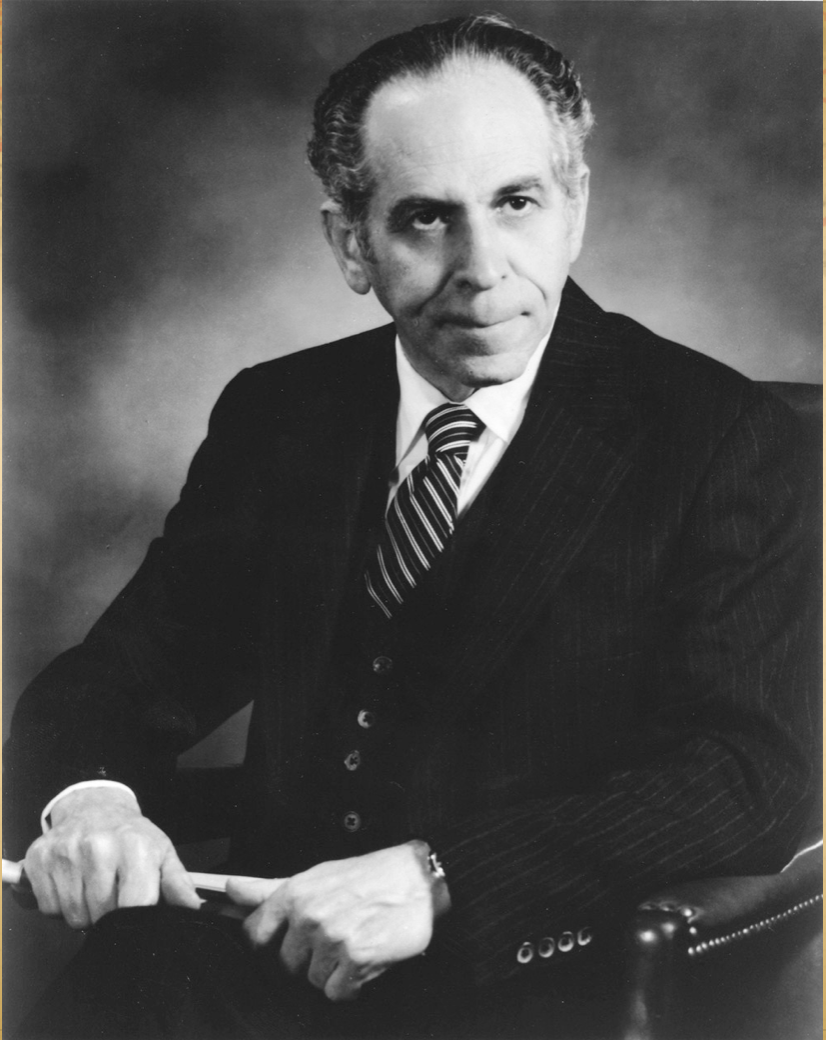

When the American psychiatrist Thomas Szasz killed himself a year and a half ago at the age of 92, I thought there would be a global outpouring in psychiatric circles of sympathy or scorn.1 Instead, his death was largely met with silence, a silence as deafening as the one that attended the second half of his long, prolific, and polemical career. Szasz’ name didn’t show up at all in the APA program last year, and this presentation of mine is apparently the only one to mention him this year. This silent treatment has, ironically enough, and surely against his will, forced him to fulfill the ancient Epicurean ambition to live and die unnoticed (in Greek, lathe biosas, ‘shun the limelight as you pass through life’).

Who Was Thomas Szasz?

I am not sure I need to tell you, but perhaps I do.

From the 1960s through the 1980s, Dr. Thomas Szasz (1920-2012) was the most famous psychiatrist on earth. Born in Budapest, he emigrated to the United States with his family as a teenager and graduated as valedictorian of his class at the University of Cincinnati Medical school. In 1961 he published The Myth of Mental Illness. It was an international bestseller. In it he argued the simple proposition that personal distress and behavioral eccentricity were being wrongly interpreted as medical illnesses, and that attempts to treat such behaviors by medical or surgical means were forever doomed to fail.

Szasz was fond of comparing psychiatry to the Inquisition, psychiatrists to witches, the mental hospital to the Church, and the medieval Age of Faith to what he called the modern Age of Madness.2 He saw psychiatry as the secular successor to the medieval practice of persecuting witches and heretics: it was, he argued, merely a change of name and rationale, rather than a change of substance, in man’s eternal quest to dominate man.3

Szasz’ interpretation seems to present us with a simple binary distinction between supernatural-religious and atheistic-materialist explanations of the world,1 much like the familiar (and ancient) debate between creationism and evolution.4 In rejecting the brain-disease explanation of mental illness, he might seem to be advocating a return to supernatural explanations. Nothing could be further from the truth, however; Szasz routinely referred to God and religion as transparent fictions, tout court. In my view, his focus on the coercive element of institutional psychiatry as the successor of mad-doctoring explains his failure to articulate the position he was advocating as clearly as he might or should have. And that in turn explains why his attempts to repeal psychiatry have failed. A comparison with the ancient Greek approach to mental illness, and especially the philosophy known as Epicureanism, will make my view clear.

First, however, since these issues tend to be fraught with emotional involvement — I imagine some of you are angry or aghast at what I’ve said already — let me now state clearly that I have no professional competence in psychiatry to endorse or reject Szasz’ ideas. My aim is merely to describe and compare them to a system of thought that flourished worldwide in an era that I do know quite a bit about.

Like vegetarianism vs. eating meat, competing explanations for the cause of mental illness are one of those social-ethical fashions that mankind rediscovers every few generations as if it has hit upon a brand new, progressive idea, and to which it goes back and forth. So too are the changing treatments. But contrary to the impression you might get from Szasz’ constant opposition of scientific psychiatry to religious witchcraft, there are not just two, but three ways of explaining so-called mental illnesses. The competition among them in the crucible of classical Greece some 25 centuries ago shows how.

From time immemorial, popular thought in Greece and Rome attributed mental abnormality, as inferred from behavioral deviance, to divine intervention. People believed in possession by supernatural forces, such as gods or demons, and sought to expiate it through the shamanistic sacrifice of animals. Jesus himself was a firm believer in demons and regularly cast them out of people. Amid the Ecclesiastical State of the European middle ages and early modern period, this belief reemerged and prevailed. According to it, the Church held that witches, possession by Satan, and Jews and heretics were responsible for mental abnormality as inferred from behavioral deviance. The sacred symbol of this view is its emblematic treatment, exorcism, or shamanic ritual.

In 5th-century BC Greece, Hippocrates introduced a new explanation—the medical model, which attributed mental abnormality, again as inferred from behavioral deviance, exclusively to natural bodily causes. Hippocratic healers believed in humoral imbalances in the brain, and sought to correct them through the use of neuroleptic drugs, forcibly administered if need be, and confinement in the clinic.5 With the dawn of the Scientific state of the European Enlightenment, this belief reemerged and has come to prevail. Because few people today really believe in demons, witches, or Satanic possession, they, and their governments, hold that chemical imbalances in the brain are responsible for mental abnormality or personal distress as inferred from behavioral deviance. The sacred symbol of this view is its emblematic treatment, excision, of parts of the brain through surgery, electroshock, or neuroleptic chemicals.

The opposition of these two approaches is well known, and figures in every history of psychiatry. What is less familiar today is that in 4th-century BC Greece, yet another view was on offer—the Epicurean model, which attributed mental abnormality, as inferred from behavioral deviance or self-report, to spiritual anguish. The Epicurean model held that man’s universal fear of death was responsible for his mental anguish, which caused and resulted from his poor choices and failure to understand the relationship between his appetites and his responsibility. The sacred symbol of the Epicurean view is its emblematic treatment, talk therapy or exercise, both mental and physical.

The competition among three different models of mental anguish—the shamanic, the medical, and the Epicurean—is hard to map onto today’s context. In part this is because the Epicurean model runs counter to modern scientific thinking. It interpreted the spirit or mind (psyche, soul), not as something immortal and God-given, but as a purely mortal and material product of natural evolution; so it may seem counterintuitive. Since most people today, and especially non-Christians, believe either that the soul does not really exist, or that the mind is just a function of the brain, they have a hard time understanding this approach. For an atheist to say we have a spirit, and to refer to “spiritual well being” (as Szasz does), may strike you as funny. Most unreligious people today would deny that human beings have a spirit. For them, humans are organic compounds of atoms, molecules, electrochemical processes, and no more. There is no room in this picture for a spirit, a word that smacks of religion, superstition, or supernaturalism. Furthermore, today psychoanalysis (talk therapy) and pharmacophysical treatment (lobotomy, electroshock, drugs) are both subsumed under the name psychiatry; whereas in antiquity, the two were in direct competition. The medical model was the province of the Hippocratic healers, or doctors. The Epicurean model was the province of the philosophers and their students. Each group explained distress differently. The philosophers, like psychoanalysts, thought the patient’s psyche was disturbed; whereas the psychiatrists, like the Hippocratics, thought the brain’s chemistry (or humors) were out of balance. (In antiquity, the shamanic model was only believed in by the lower classes and because it is obsolete today, it does not interest us here.)

It is the Epicurean model, I suggest, that Szasz himself hit upon and developed independently—though he was apparently unaware that he was reactivating a view that was not only ancient, but that had once been massively influential on civilized man, and for seven centuries.

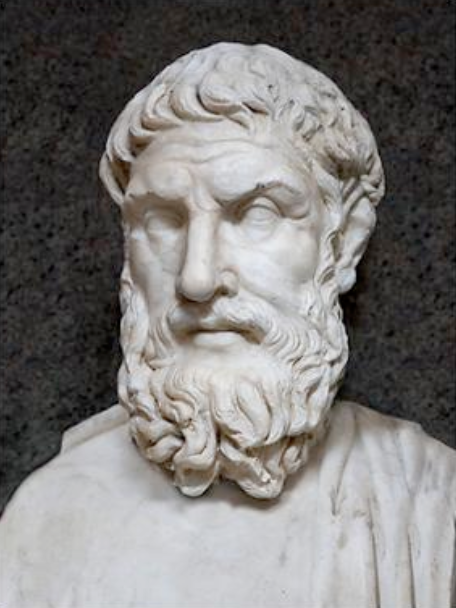

Who Was Epicurus, and What Was His Philosophy?

Born in Samos (Greece) in 341BC, he emigrated to Athens and founded a philosophic school at his private residence, the Garden. Epicureanism soon became the largest of the three main schools of Hellenistic philosophy, overtaking Skepticism and Stoicism. In the wake of Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and beyond, it soon spread to become a world philosophy. It was dogmatic and missionary, transmitted not only by one person to the next but especially through books — books of aphorisms, a manifesto (the tetrapharmakon), and graded textbooks. It met with opposition, first from rival philosophies (Platonism, Stoicism), then from religions (Judaism, Christianity).6 After Epicurus’ death in 270 BC, adherents of his philosophy could be found across all of Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and India. It was especially popular with the middle or bourgeois classes in the vast Roman Empire. It thrived for seven centuries, dying out in the 4th century AD, when it was swamped by Neoplatonism and Christianity (belief in which became legally mandatory in 381 AD). Thereafter, it slumbered for some 12 centuries. In the Renaissance, it revived and gave the chief impetus to the Enlightenment. Thomas Jefferson is only one of several famous self-affirming Epicureans of modern times.

What tenets did Epicureanism hold? Epicurus preached a materialist philosophy. It was rooted in recent scientific speculation about the physical world. He believed everything in the universe was made up exclusively of atoms and empty space, or void, for the atoms to move through. As they moved, the atoms collided at random to form compounds, like water, air, trees, people, planets, and so on. He thought human and animal life arose purely through evolutionary processes; that is, no god created it, no god looked out for it, and no god was preparing rewards or punishments for life after death, because the soul or mind, which was just another collection of atoms, did not survive death – nothing did. Because there was no life after death, there was no heaven and no hell, and the gods, though they did exist, did not care what we humans did or did not do to one another.

This physical outlook necessitated a new moral outlook on human conduct. Epicurus preached that all social arrangements, such as justice, were simply convention. The highest aim of his philosophy was therefore individual pleasure – by which he meant, not binging on food, drink, or sex, but simply acquiring the minimum pleasure necessary to avoid pain. In short, he preached freedom from fear — the fear of death, which he considered the source of human anxiety. The goal was to achieve mental health (ataraxia, tranquility of the mind or soul) by realizing that there is no life after death, and hence nothing to fear from dying. You will surely recognize this as the forerunner of the contemporary secular humanist lifestyle.

His philosophy was, in other words, psychiatric. Talk therapies were explicitly meant to heal the soul and relieve its anguish. If you had told Epicurus you could “fix” a man’s disordered thoughts by shocking or lobotomizing his chest (wherein he thought the soul resided), he would have laughed or cried or tried to talk you out of it. So too, I suspect, with neuroleptic drugs. Epicurus would surely have agreed that disrupting or destroying your body’s material substructure will cause you to think differently, but he would not have agreed that such means could relieve you of your fear of death. While he and other philosophers were trying to reason people into correct opinions, do recall, the Hippocratic soul healers were trying to cure insanity with hellebore, the neuroleptic drug par excellence of antiquity; and the regular folk were still using shamanistic expiations.

Epicurus made no effort (to our knowledge) to oppose the Hippocratic healers, but he certainly opposed religious expiations as pointless and evil. For Lucretius, his great missionary in Rome, the sacred symbol of evil done in the name of traditional piety was a human sacrifice – specifically, the deliberate sacrifice of Iphigenia, the eldest daughter of King Agamemnon in Greek mythology, when he found his political ambitions blocked. For Szasz, the sacred symbol of evil done in the name of psychiatric piety was also a human sacrifice – specifically, the willing sacrifice (as he put it) of Rosemary Kennedy, the eldest daughter of Joe Kennedy, U.S. ambassador to Britain in 1938 and father of U.S. President John F. Kennedy. In Szasz’s account,7 Joe agreed to lobotomize his own daughter when he found his political ambitions blocked.

Another feature distinguishes Epicurus’ philosophy from that of his rivals and makes it resemble Szasz’ philosophy. That is that he was metaphysically a libertarian:

that is, he believed above all in free will. For him, the soul was certainly a bodily organ (located in the chest), but in his view free will and reasoning emerged from this material substrate, enabling man to break the deterministic chains of Fate and become a moral agent. By persuading a man to reason his way out of irrational fears, such as that of death, man could in turn act upon his atomic makeup, his body, and achieve inner peace. “Human nature is not to be coerced but persuaded,” said Epicurus (Vatican Saying 21, trans. DeWitt). The maxim could have come verbatim from Szasz’ pen.

In fact, mutatis mutandis, everything I have just said of Epicurus is also true of Szasz’ thought. It can be illustrated in almost any of his books.

This view of the soul or mind stands in contrast, by the way, to that championed by Stoics in antiquity and by psychiatry coursework today. Many people suppose that if our thinking occurs in our brains, and is not directed or controlled by gods, then we are foreordained to behave as we do. The Stoics called such determinism, or causes (rather than reasons), to Fate; whereas today we attribute it to genes or chemical imbalances in our broken brains.

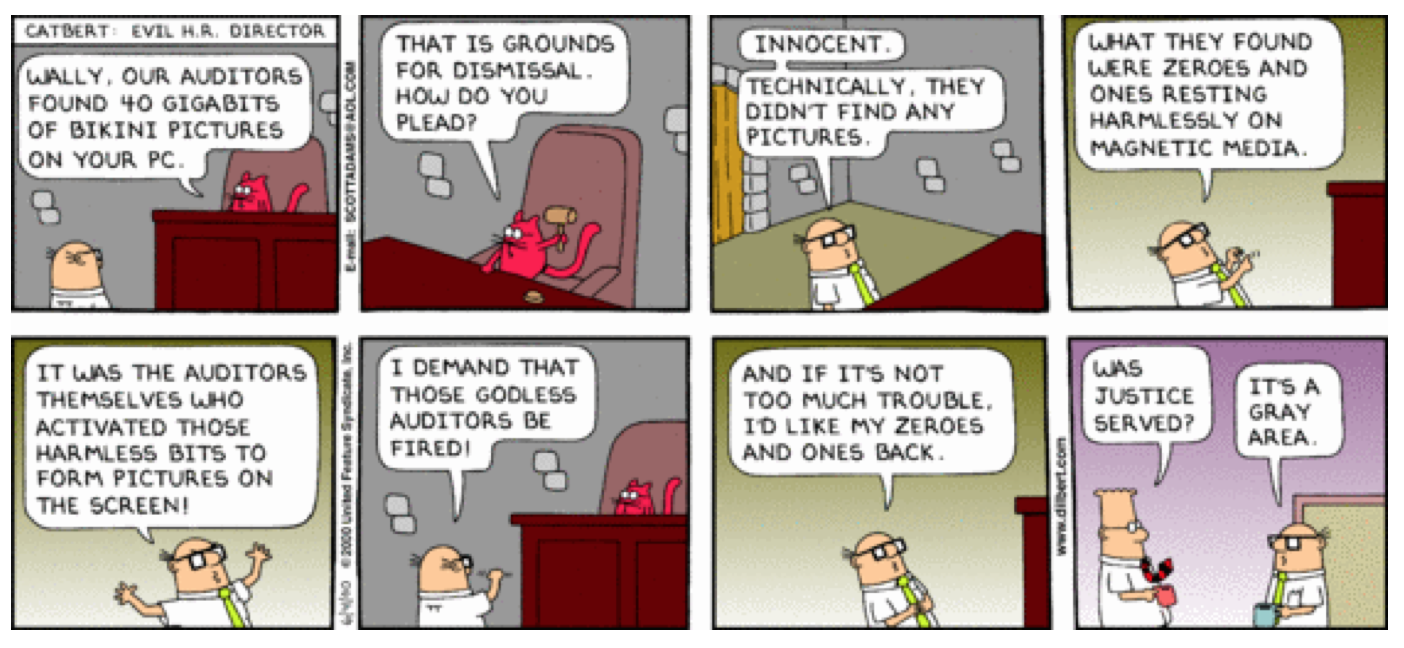

Szasz and Epicurus would both have opposed such thinking as simplistic and overly reductive. What does that mean? Let me illustrate the point with a cartoon. Here is a “Dilbert” cartoon from June 4, 2000, that puts the matter simply.

My interest is in the first four panels. In them Dilbert is caught with risqué photographs on his computer at work. What is his defense? That the pictures are “really” just strings of ones and zeros—that is to say, just binary code. Mutatis mutandis, Szasz or Epicurus would say, those who believe that people behave oddly because their brains are misfiring, instead of acting as they do for reasons they themselves deem appropriate, cannot see the pornographic motives behind strings of binary code.

If their philosophies were indeed similar, why did Epicureanism flourish where Szaszianism has failed? I ask because although he suggested and advocated many, Szasz cannot be credited with implementing any psychiatric, social, political, or legal reforms, save perhaps deinstitutionalization. His philosophy, and especially his chief claim that mental illness is not a medical disease, has not spread throughout the world; rather, it is psychiatry that has flourished and grown worldwide, and has spread throughout all classes in the West.

It cannot be just that Szasz was wrong, if you believe him to be so. Wrong ideas win all the time.

It also cannot be because of their principal tactics of persuasion. Both men liked and employed satire, aphorisms, dogma, candor, and arguing from the excluded middle. Both wrote in the global lingua franca (Greek, English), enjoyed translations, and enjoyed easy access to disseminating their ideas in print.

Clip from “The Last Interview of Thomas Szasz,” a film by Philip Singer, Ph.D

(Trailer below)

There are, to be sure, some signal differences. Epicurus founded a school and named it for himself. He demanded loyalty pledges of his students. He wanted, and became, the Greek messiah. By contrast, Szasz worked at a school. He demanded loyalty pledges of no one. He had no interest in becoming, and did not become, the psychiatric messiah. He believed too firmly in autonomy and individualism for that.

One possibility is that Szasz’ opponents reinterpreted his ideal, autonomy, to mean selfishness, just as Epicurus’ opponents twisted his ideal, pleasure, to mean hedonism. No one wants to be called a glutton or selfish; but I don’t think this explains his failure.

Rather, it seems Epicureanism spread because its endpoint was popular. People wanted to believe there was no (horrible) life after death because its physicalist-atheist underpinnings made sense to them and because believing in it freed them to pursue pleasure, however they defined that word for themselves.

Szaszianism also preached freedom—not from the fear of death, but from coercion. His highest aim, autonomy, sounds pleasant, but it is not. Framed as freedom, autonomy sounds grand. Framed as personal responsibility—accountability, answerability, paying the price, failing—it is exceedingly unpleasant. Therein lies the difference. Pleasure and personal responsibility are not merely different; they are often polar opposites, as we can see when manifested in the case of, say, obesity or alcoholism, and the various treatments of them.

In short, Szasz failed not because he was wrong but because he championed an ideal, personal responsibility, that few want to accept. As he knew and said, responsibility is something man is forever hoping to avoid and displace onto another; hence his attribution to Satan or illness as the agent “really” responsible for his poor choices. It is more pleasant to blame his failings on demons, witches, his genes, or his metabolism for his gaining weight—anything but himself.8 The fact that bariatric surgeries, and the unending quest for a weight-loss pill, are on the rise suggests that in the short term, Szaszianism will never succeed.

The other reason Szaszianism has failed is because—on my evidence— psychiatrists do not know what philosophers have to say about the mind or soul. They are committed to the Hippocratic, reductionist-materialist view that it’s just the brain. They aren’t taught that other views are out there. Perhaps they should be.

* * * * *

Download the handout for the talk at the APA here.

The Last Interview of Thomas Szasz,” a film by Philip Singer, Ph.D, is a documentary exploring the controversy & beliefs of anti-psychiatry psychiatrist Dr. Thomas Szasz. For more information please go to Witness Films.

References

(For undocumented statements about Epicurus and Epicureanism, see De Witt, O’Keefe, and Warren.)

De Witt, Norman. 1954. Epicurus and his Philosophy. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Fontaine, Michael. 2013. ‘On Being Sane in an Insane Place—the Laboratory of Plautus’ Epidamnus,’ Current Psychology 32.4 (2013), 348-365.

O’Keefe, Tim. 2010. Epicureanism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Szasz, Thomas S. 1973. The Age of Madness: The History of Involuntary Mental

Hospitalization Presented in Selected Texts. Garden City, New York: Doubleday Anchor. —. 1988. The Theology of Medicine: The Political-Philosophical Foundations of Medical

Ethics. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. (Original work published 1977.)

—. 1997. The Manufacture of Madness: A Comparative Study of the Inquisition and the Mental Health Movement. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. (Original work published 1970.)

—. 2007. Coercion as Cure: A Critical History of Psychiatry. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2007.

—. 2010. The myth of mental illness: Foundations of a theory of personal conduct. New York: Harper Perennial. (Original work published 1961.)

Warren, James. 2007. The Cambridge Companion to Epicureanism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Footnotes:

1. Szasz committed suicide at home on September 8, 2012. His 855-word New York Times obituary is found here. Jeffrey Schaler’s more informative obituary (“Kaddish for Thomas Szasz”) is found here.

2. The Age of Madness, introduction, and The Manufacture of Madness.

3. The Manufacture of Madness.

4. Epicurus, like many other ancient thinkers, believed in evolution.

5. For evidence and references, see Fontaine 2013.

6. In Rabbinic Hebrew, Epicurus’ name became the word for “infidel,” “heretic,” “unbeliever”.

7. Coercion as Cure, pp 152-3.

8. The Theology of Medicine.

* * * * *

This is too much bs to process right now but wanted to he first to put in my kudos to Szasz till I have the patience to “properly” respond.

Report comment

Agreed this is too much bs and also with the kudos to Szasz.

In fact, a much more accurate description of his legacy is can be found here,

http://www.madinamerica.com/2013/05/the-myth-of-mental-illness-revisited-nimh-style/

The bottom line is this: Szasz’s message that no label listed in the DSM has been shown to be a brain disease won over both the NIMH and, at least partially, the APA.

Mainstream psychiatrists are just too proud to admit the obvious. For those of us who have no dog in the fight of who gets what federal dollars, it is patently clear that the current crisis in psychiatry was caused by Szasz.

Report comment

I invite you both to present critiques with more substance than “this is bs,” which is pretty dismissive and disrespectful to the author who put thought into this piece.

Report comment

I would like to add to Emmeline’s comment that if Mad in America is to be taken seriously, it will involve more thoughtful discussion than “this is bs.”

I am excited to have such a thoughtful piece as this on MiA. I know that Mr. Fontaine has put considerable thought and time into it, including time spent with Thomas Szasz.

When Szasz died I was appalled at the lack of coverage and, where there was any (the New York Times), it was clearly unappreciative and uncomprehending of his true message. I tried at the time to solicit some articles to try to fill the gap a little, to some success. But when this article showed up, I was very excited at the depth of information, thought, and appreciation reflected in it.

These days, unfortunately, aligning oneself with Szasz is a risky thing to do; one gets too easily tarred with various unfair labels, all missing the point. If MiA is to move the conversation forward, it will require expanding the conversation around these issues, not shrinking it, until people can see that the concerns we write about on MiA actually do have meaningful connections to all of human life. A piece like this, taking its inspiration from the ancient history, written by a classics scholar, is the kind of article that expands the range and depth of the dialogue, and we are lucky for it.

But having the first comment be “this is bs” sends a message to the world about who MiA readers are and, unfortunately, people draw conclusions about what MiA’s mission is. Those who would wish to dismiss us are given all the ammunition they need with such careless comments. No matter how many reasoned, thoughtful pieces we publish, people conclude – or are allowed to continue to believe – from such offhand comments that this is the true spirit of MiA; this fact has severely limited the pool of authors we can draw from, and the range and quality of the discussion we can have.

On the other hand, MiA considers it a profound responsibility to be as unrestricted a forum as possible, because we feel a profound obligation to people whose voices have not been heard. We like to think we offer a unique forum that has not existed, for people who have been harmed to speak to those who are at least a little open to hearing and changing the dialogue.

So, Emmeline has properly chosen to let these comments stand. But I am saddened that articles that offer such a unique contribution to the conversation would be met, first, with such uncomprehending, dismissive comments. The article may not be your cup of tea, but comments such as these have the effect of dampening the pleasure others find in it. I think that if you look deeply in the article, you find an elegance of thought that can be applied far beyond these relatively circumscribed conversations. It is articles like this that help people realize that we are trying to do more here than thrash out past grievances; we are trying to reconnect conversations about human struggle, which have been made paltry and irrelevant by the false promises of a medicalized solution, to discussions that can encompass human aspiration as well as the beauty and joy to be found by transcending our material being rather than surrendering to it.

That is what a return to the classics can help us appreciate in a unique way, and why I was thrilled to be able to post this article. I hope that the conversation proceeds in a more meaningful and inspiring – or at least appreciative and polite – way from here forward.

Report comment

Emmeline/Kermit,

More later today then. The summary of what my critique will be is this: the author is pulling a straw man. Thomas Szasz was not in the business of religion or providing world views to people. It’s the other co-founders of CCHR who were/are.

Thomas Szasz true legacy is more similar to Martin Luther King’s than to Martin Luther the monk.

I will detail this when I have the time later.

Report comment

Yeah I understand all the concerns about propriety etc.; I made my comment anyway and hope that my deliberate provocativeness will help infuse some passion into what some apparently feel should be an emotionless la-de-da tea-time debate.

Lives are at stake here. Szasz’s deconstruction of the semantic obfuscation of psychiatry has set the intellectual foundation for our liberation, and many of us don’t take kindly to these sorts of hit pieces framed in the trappings of reasoned discourse .

Unless subsequent posters make it unnecessary for me to do so I also plan a more polite response after I’ve had the chance to draw in a few more deep breaths.

E & K I know you’re in a difficult position here, just trying to do my job as you are yours. 🙂

Report comment

Why bs? I don’t agree with every statement the author wrote but it’s a nice reminder that the ideas have been around for hundreds of years. As for whether Szasz succeeded or not and – well, that’s the point where I disagree with the author, mainly on the reasons why current psychiatric model is so popular.

Report comment

Interesting article. Does lack of popularity equal failure? And even if it were so, has the story ended, that we can say who has won and who has lost? Does the story ever end?

RIP, Dr. Szasz. You will live forever.

Report comment

I agree. Not fair to pick on DR. THOMAS SZASZ,just because he had died.

I heard he’d lost a lawsuit (foolishly filed by a family whose member was on lithium and committed suicide). SZASZ tried to get the guy OFF lithium. SZASZ was NOT discredited;he was OVERPOWERED and that’s a different matter.

Who will succeed SZASZ? Dr. Jeffrey Schaler? Dr. Peter Breggin? SZASZ left some mighty big shoes to fill. CCHR keeps SZASZ’ memory alive.

Report comment

Excuse me, institutional psychiatry (imprisonment in mental hospitals) is the successor of mad-doctoring (i.e. the trade in lunacy [or imprisonment in private lunatic asylums]), both are coercive.

Slavery is another coercive practice that Szasz compared with coercive psychiatry. It might be too easy to miss the success of Szasz for the failure of Epicurus. (Seems his school has been out of session for some time now.) If John Brown was instrumental in launching the war that freed people of color from the bondage of chattel slavery, well, there you go. I wouldn’t be too quick to dismiss Dr. Szasz as an abject failure. (Sure, I’m partial in making this little leap of faith, or is it judgment.)

I have a big problem with this blind spot that psychiatry has regarding the harm that it sows. This harm comes directly out of its “coercive element” to put the matter altogether too mildly. Coercion (and the various forms of violence and torture that go with it) should not be trivialized as mere subjects for academic discussion.

Degrading people into statistics may have its rewards, but I would hope we can find some punishments for it myself.

Report comment

You are certainly right about psychiatrists not understanding philosophy. I’m not trying to bash Epicurus. (Isn’t the Epicurean motto: moderation in excess?) Thomas Szasz objected to coercive psychiatry on moral grounds. It denies moral agency to those whom it labels, studies, and mistreats. It does so on would-be medical grounds, but those medical grounds are a fantasy. Psychiatry would deal with magical thinking through its own form of magical thinking, and what you don’t get out of compounding magical thinking with magical thinking is realism. If a person were to seek a guide in a hospital, what would they get out of the effort? Probably a pill. Problem is, the pill won’t lead to a good place, quite the reverse. Especially when the pill has an actual adverse effect on the physical body. The mental body can take it. Robbing people of the opportunities that were promised them is no way to “heal” them, call it what you will.

Report comment

“Isn’t the Epicurean motto: moderation in excess?”

I’m not familiar with this formulation but it sounds like a spoof or caricature of the Epicurean ideal. Epicurus advocated moderation as the ideal way to live. The expression “the golden mean” is one ancient expression of that ideal, and Epicurean poets in antiquity — Horace, Virgil, probably Catullus — celebrated it repeatedly. Like the Epicurean ideal of pleasure, however, it was easily caricatured by his opponents. That is why the name Epicurean today typically conjures up associations with eating deliciously or excessively.

Report comment

I agree with Uprising and Frank (above)

I appreciate your efforts Michael to think creatively about Szasz, but your analysis, although erudite and eloquent, strikes me as naïve. First of all, let me clarify a possible misunderstanding that I fear may create the wrong impression , that may be interpreted as an expression of defeat or despair by Thomas Szasz. You start by saying Szasz “killed himself.” While technically true anyone who has read Jeffrey Schaler’s account knows that this was not an act of desperation but a reasoned decision based on considerations of health at 92. And of course Szasz had written prolifically on suicide as a right and a rational decision. Just to clear that up, Michael–for those who do not know.

You write

“In my view, his focus on the coercive element of institutional psychiatry as the successor of mad-doctoring explains his failure to articulate the position he was advocating as clearly as he might or should have. And that in turn explains why his attempts to repeal psychiatry have failed.”

And you write:

“In short, Szasz failed not because he was wrong but because he championed an ideal, personal responsibility, that few want to accept. As he knew and said, responsibility is something man is forever hoping to avoid and displace onto another; hence his attribution to Satan or illness as the agent “really” responsible for his poor choices. It is more pleasant to blame his failings on demons, witches, his genes, or his metabolism for his gaining weight—anything but himself.”

Let’s take this: “In my view, his focus on the coercive element of institutional psychiatry as the successor of mad-doctoring explains his failure to articulate the position he was advocating as clearly as he might or should have. And that in turn explains why his attempts to repeal psychiatry have failed.” In the first place I strongly disagree with you. I read at least 15 books and many articles by Tom and I think he very strongly and very clearly advocated his belief in autonomy.(You are right that autonomy was probably his primary value.) Second, and more importantly, separating his commitment to autonomy from the oppression of mental patients would have made Szasz an armchair philosopher and not a prophetic advocate, at best an academic mediocrity if not a hypocrite. (I expect you will disagree–so I’ll return to this issue later.) Finally your own explanation for his “failure” overlooks much of Szasz’s argument, which I think explains BEST why his “failure” was almost inevitable– at least in the short run.

Your argument is like saying there is a plutocracy in America because Americans were not willing to accept the idea of equality. You completely overlook the will to power that Szasz finds at the basis of modern psychiatry. This put Szasz in the same boat, to his chagrin, with leftists psychiatrist R. D Laing (who was, contrary to your assertion, the most famous psychiatrist in the 1970s and 80s–more so than Szasz) and philosopher Foucault whose deconstruction of the Panopticon is too often overlooked. One must examine the dialectic of domination in psychiatry and the ideological ruses it assumes which make it appear as a medical enterprise undertaken for the benefit of patients. You cannot understand history if you assume the Masters and the slaves have equal access to knowledge–are equally powerful, have equal means to propagate their ideas. You write as if you assume the best ideas will “win” in the marketplace of ideas as long as they are CLEARLY articulated. My God, read Thomas Kuhn, Noam Chomsky, liberation theology, Anabaptist John Howard Yoder, Marx, Weber, Gramsci, Mills, Breggin (on the psychiatric-pharmaceutical complex), Healy, Whitaker, and Laing.

I included religious thinkers because the Marxist notion that religious ideas are inevitably reactionary is very wrong. There are two modes of Western religion–Constantinian and anti-Constantinian.The former is religion in the service of economic elites and the State and the later is religion in the service of equality, in the service of all beings. It is Constantinian religion –of which I claim psychiatry is a secular expression— which help explain why Szasz “failed.” I make this point in all of my books. At any rate,to reiterate, the success you claim eluded Szasz would have been inconsequential for humanity. It would have excluded the “severely mentally ill”–those for whom Tom was a vigorous advocate. It is better that his ideas live on–even as a thorn in humanity’s flesh, a goad to create a more equal world in the future.

To quote Marx,“The ruling ideas of an epoch are the ideas of its ruling class.” That is not always true but it is the reality every revolutionary(and I do not necessarily mean Marxists) must confront in “normal” times. Tom’s greatest insight–and he shared this with Laing, even though Tom would not acknowledge Laing– was that psychiatrists were the secular priesthood of the current social order.They sanctified it–they defined “reality.” (Tom’s idea were hobbled by his economic Libertarianism which became more pronounced and stingy as he got older.For example his opposition to any Soteria type asylum.)

Why do you think Szasz compared Psychiatry to the Inquisition? The priesthood legitimizes and sanctifies the power of the dominant elites. And like the priesthood Psychiatry maintains social control. BTW Tom’s antipathy toward Laing abated ephemerally in the early 90s after Laing’s premature death, and Szasz wrote the Foreword to my first book, despite its quasi Laingian spiritual argument, Madness, Heresy and the Rumor of Angels: The Revolt against the Mental Health System. Ron Leifer,a dissident psychiatrist and Buddhist, was a protégé and friend of Szasz (and later of mine) whom I interviewed for that book–- Ron did not go along with Tom’s unfortunate opposition to any equalizing role for Government.

Szasz’s point was Psychiatry like the Inquisition (see,The Manufacture of Madness) was not really concerned with the cure of souls but the persecution and control of social deviants (“witches,” Tom argued, were not “mentally ill” –the revisionist Psychiatric position–but indigenous local healers, usually female, who competed with priests as healers) including heretics. Leifer, a psychiatric heretic, had lost his job at the University–(SUNY-Rochester) when he defended the tenured Szasz whom the University was trying to silence. Szasz lost his classes and Ron lost his job. AS did Ernest Becker who also defended Szasz. You overlook the fact that Szasz repeatedly claimed that the real goal of Psychiatry was not cure of souls, but social control–a point made by powerfully by Leifer in In the Name of Mental Health.

In Szasz’s book on the Inquisition he predicted coercive psychiatry would continue until humanity gave up its tendency toward “existential cannabalism”–that is until the powerful repudiated the will to power.

You write,”In short, Szasz failed not because he was wrong but because he championed an ideal, personal responsibility, that few want to accept.” Again you are over-simplifying. Szasz’s work gave rise to the mental patients’ liberation movement–and that movement ought not be lightly dismissed.(You do not even mention it.) Despite complaints about its own under-emphasis on responsibility, it accepted personal responsibility(which includes the right of freedom and autonomy) in principle and it made the achievement of full citizenship rights and responsibilities part of its program, albeit unachieved. Thus it became a social force that embraced and symbolized the ideal of personal responsibility-–among the lowest caste of “schizophrenics” no less. He could not have done THAT had he adopted your Epicurean strategy–and that would have been an ineffable loss.

But you keep conflating the Master and the Slave. It’s like saying slavery was supported in America because Americans could not accept the idea of equality. Blacks did support equality and by the civil war most abolitionists did as well. Those who had a financial interest in slavery did not accept equality. And they had the economic means to promulgate their ideas.(Only a minority in the South had actually owned slaves.) Remember psychiatrists had a diagnosis for slaves who ran away from slavery—a pathological condition termed “drapetomania” (cited by Szasz) described by physician Samuel Cartwright in Diseases and Peculiarities of the Negro Race.

No your study of Szasz is creative and noble but your idea that he should have abandoned his advocacy for “the mentally ill” and thus presumably been more acceptable is misguided. Perhaps you think he would have gotten psychotics in the master’s house that way through the back door.AS someone who worked in these clinics in the 1980s, before and after I got my PhD, I can tell you it doesn’t work that way. The idea that psychotics were “severely and incurably disabled” was an intractable self fulfilling prophecy. Szasz greatest accomplishment may well have been that his ideas empowered the oppressed –the “schizophrenics”–and gave rise to a movement that proved the psychiatric narrative was wrong.

I must admit in my current writings I reject the secularism of the Szaszian narrative. I argue it is time to go beyond the Szaszian phase, the Enlightenment phase, of the survivors’ movement –without abandoning it– onto a second phase of the movement,by explicitly affirming the spirituality of the Mad, by emphasizing the gifts of the Mad, by helping the mad to complete their initiation as prophets, poets and visionaries of humanity. That was the theme of my article published here shortly after Tom died.

http://www.madinamerica.com/2012/11/szasz-and-beyondthe-spiritual-promise-of-the-mad-pride-movement . My newest book of the Mad Pride movement is called The Spiritual Gift of Madness…

Thanks for your contribution.

Best, Seth

Seth Farber, Ph.D.

http://www.sethHfarber.com

Report comment

CORRECTION: SUNY- SYRACUSE

is where Tom and Ron Leifer were.

SF

Report comment

Thank you for your reply, Dr. Farber. Let me address some of your points in the same order you did.

I published my thoughts on Dr. Szasz’ suicide in a letter just uploaded to Szasz.com. In choosing the time and means of his death I believe he was self-consciously acting in the tradition of Socrates. You can find my reasoning here: http://www.szasz.com/szaszfesttwo.pdf.

In the second instance you object to the same sentence that an earlier commenter did, which I agree was badly worded (and which I replied to above). You write, “I read at least 15 books and many articles by Tom and I think he very strongly and very clearly advocated his belief in autonomy”. You raise a good point. Did Szasz value autonomy or freedom more highly? Are the two words simply synonymous, the one Greek and the other Saxon? It would be helpful to find a statement from him on the matter.

From your description of “Constantinian religion”, a notion with which I’m familiar only from your comment here, as well as the sweeping Marxian analysis of history and notion of “the Mad” that you offer, I will respectfully disagree. Of course power is at stake, as I thought I made clear — insufficiently so, evidently.

On your final point, I didn’t suggest, nor meant to suggest, that Szasz ever did or should have abandoned his advocacy. As I make clear in the letter linked to above, I believe his suicide was the final act of his lifelong advocacy.

I thank you again for your critique.

Report comment

Well I’m afraid I misunderstood you to mean Szasz’s FOCUS was the problem.

Well if not you have attributed Szasz “lack of success” to two contradictory causes. On the one hand, Szasz you claim is unclear about autonomy. His lack of clarity is why he has not been able to “repeal psychiatry.” On the other hand, you tell us his account is rejected because it is unappealing because people do not want to be autonomous because that is to be held accountable.. If the latter is true than his lack of clarity is irrelevant.If anything it should only make his account more appealing.

Certainly Szasz’s account could be both unclear and unappealing. But you cannot invoke contradictory ideas to explain his “lack of success.”

On the one hand you say he failed because he did not make himself clear to psychiatrists. On the other hand to the extent that he made himself clear you say

his model alienated people.

You do not even address the problem Szasz considered central: The mental health system destroys and dehumanizes those it claims to help. You don’t present a solution. You treat that problem–integral to Szasz’s ouevre–as if it is parenthetical. Szasz deals with human suffering.

Second you certainly did NOT deal adequately with the issue of power. You say “power is at stake” But your model completely ignores power. You mention it but you don’t include it in your explanatory schema. Virtually everything Szasz wrote was based on the idea that psychiatrists’ goals conflicted with the goal of those citizens who are deemed mentally ill. You completely ignore this and seem to imply that Szasz would agree with you that had he been clearer and had his account not frightened people with talk of accountability(a contradictory position, I repeat) then Szasz would have been “successful.” But that is nonsense because Tom knew that the interests of psychiatrists and that of “mental patients” conflicted.

The former wanted to exercise social control–that is their social role for which they are remunerated. The latter do not want to be controlled (under the guise of being helped), they want the rights of citizens, they want the abolition of forced treatment–they want them even at the cost of being held accountable, of bearing the burden of freedom because this is what it means to be human.

Your piece is based on the canard that Szasz could have appealed equally to mental patients or psychiatric survivors AND to psychiatrists—and been “successful.”. Szasz’s model is based on conflict. And because psychiatrists and the State–and I would add the billion dollar drug companies– have more power they will win–in the short run. You write,” His philosophy, and especially his chief claim that mental illness is not a medical disease, has not spread throughout the world; rather, it is psychiatry that has flourished and grown worldwide, and has spread throughout all classes in the West.” You are not judging Szasz by the standards of Epicurus–you are judging him by the standards of Batman! Captain Marvel. Napoleon. It’s an unfair and meaningless comparison.

Your model is based on the idea of a harmony of interests between mental patients and psychiatrists.That is in fact the verdict of consensual reality: Psychiatrists treat patients. You don’t seem aware that Szasz deconstructed this myth of harmony, this ideology of doctor and patient. His accomplishments were intellectual and moral. But you don’t understand that because you’re oblivious to the suffering of people n the mental health system–or if not you’re not letting readers in on your awareness.

But you have no solution. You tell us that if Szasz was only less confusing he would have repealed psychiatry. This would be like telling Trotsky if his writing were less rhetorical he would have convinced the capitalists to stop exploiting the workers, and there would not have been a need for a Russian revolution!! I am not a Trotskyist–I use this as an analogy to emphasize your failure to grasp the conflictual nature of Szasz’s model, the conflictual nature of human society.

There is only one way to get around this problem. The only place I recall Szasz discussing it explicitly was in The Manufacture of Madness, published in 1970.In this book Szasz appeals to humanity to give up “existential cannabalism.” By existential cannabalism Szasz means e.g.,the psychiatrist enhances his own status by destroying the meaning other people–his patients–give to their lives. In this book Szasz posits that humanity will evolve spirituality so that enough of us will give up cannabalism to transcend the conditions that threaten to destroy all of humanity.

In his other books Szasz is not explicit. He appeals to human beings’ sense of morality. Whether he thinks he will be successful or not is unclear. But Szasz at least had a criterion of success. It would be ending exploitation in the mental health field.Of course he knew one person or 1000 persons could not achieve that goal. (Furthermore that is only one domain.) I don’t know whether Szasz thought his work advanced that goal.

Epicurus, you say, was “successful” because he had lots of followers. And Szasz didn ‘t.There is another criteria you present of success. But you tell us Epicurus had a lot of followers because he avoided dealing with the issues that disturbed people. In other words he was evasive. So what is the point of the comparison? The Moonies have many followers. The Scientologists have many followers. The Hari Krishnas had more followers than Szasz. That does not make them more “successful.” Szasz did not want followers. You picked a catchy title but it seems to me to be an unfair and meaningless comparison.

Seth

Seth Farber, PhD

Report comment

Seth: You note that masters have more information than the slaves. This was especially true when I was institutionalized. I was certainly given no contravailing information, like the works of Laing, Szasz, or Foucault, so as to give me the autonomy to decide for myself. This was 1989′ only about five years after the “Mental Patient” Liberation’s successful demonstration at the psychiatric conference.

Report comment

Thanks for your comment, Mr. Blankenship. Regarding the relationship of mad-doctoring to coercive institutional psychiatry (your first sentence), I believe we are saying the same thing, though I now see I may have worded my statement poorly. I simply meant that his focus on the coercions inherent in institutional psychiatry tended to draw attention away from the real-world implications of just what “freedom” means (since freedom and responsibility are the “positions,” or rather ideals, that he advocated). Szasz certainly did say that freedom won’t necessarily make you happy; he only said so much less often than he might have.

Report comment

I haven’t met many descendants of slaves who want a return to the practice of slavery. Not being a slave, I’d say freedom and responsibility are less ideals than they are realities, and if they’ve become ideals, unreachable goals, basically illusory, as some suggest, we’ve got a problem. I don’t think they are illusory. I think we can say with more certainty that freedom is more likely to make a person happy than slavery. Additionally, I think we can safely say that slavery is more likely to make a person miserable than freedom. Were happiness the highest aim, and I question that assumption, I am certain that the way to it is not going to be through bondage to the will, whimsy, desire and demands of other people who imagine themselves to be superior. We can pretend that free people are slaves but, all the same, they are free people, and as such, they are free to engage in any such pretense they choose. Coercion, let me state, is no way to happiness either, at least, in so far as the coerced are concerned. The problem I have, Mr. Fontaine, with your post and presentation is the abstractness, and the distance, from your subject matter that you seem to maintain. Epicurus was a contemporary of slavery; Thomas Szasz of coercive psychiatry. One thing Szasz had in his day, over Epicurus in his, was the example of the abolitionists. Slavery ran its course, and coercive psychiatry will run its course. It is a course that will not be run by keeping people in bondage. It is a course that will be run when they are liberated from bondage. The poet Robert Bly once wrote a poem about casualties from the Vietnam war reduced to figures on newsprint. This is what I see in your post, too. Given the great man theory, the life of Napoleon was taken to be more valuable than the lives of thousands of other men. How many patients’ lives, for instance, is the life of any one psychiatrist worth? That’s a pretty unsettling question, isn’t it? I guess you knew your audience. I don’t think it’s the kind of question that would have gone over at an APA convention.

Report comment

The battle for human right is a battle never to be won… or lost. It continues and will go on as long as humanity exists.

Report comment

Has anyone noticed that almost all humans spend the first three years of their lives being completely dependent on someone who has to put their autonomy second, at times, on behalf of the dependent one?

Report comment

I’ve always wanted to bring childhood up in the context of ‘nature versus nurture’ arguments. We don’t have one here, but how appropriate anyway.

In primitive cultures, the dividing line between adulthood and childhood was something like reaching the age of 12. In more modern cultures, it is around the age of 18, or by extension, 21.

Mental health law would retract age of consent laws, and thus some major leaps of judgment have been made about the perceived, or the impugned, childishness (always unproven beyond a reasonable doubt in any court of law) of certain adult individuals. Mental health law, in my view, is illegal or unconstitutional law.

Implicit in the freedom to bear children is the responsibility for their welfare. Reneging on this responsibility can result in removal of the child, if the evasion is caught, or punishment, if the child is injured or dies. Here, as you can see, I don’t think the someone you refer to has put their autonomy second. I think that someone has put autonomy first, and here sacrifices come out of the autonomous decisions made for the sake of delayed and/or immaterial rewards.

A baby left to its own devices will perish. The innate survival (thrival or whatever) gene must be entirely lacking at such an early age. Explain that one.

Report comment

“authority, unless justified, is inherently illegitimate and that the burden of proof is on those in authority. If this burden can’t be met, the authority in question should be dismantled.” N. Chomsky

A toddler is not able to express substantial autonomy but a 9yr old can and a teen definitely can.

Report comment

CORRECTION

SUNY-SYRACUSE

is where Szasz and Leifer were

not Syracuse.

SF

Report comment

I must say that I found this post offensive because it seems that Michael was/is trying to be very provocative about Dr. Szasz in his presentation when he is writing for a critical or even antipsychiatry group who tend to admire those few heroes who exposed the truth about psychiatry and the so called mental “health” system at huge cost to themselves.

The following article shows that psychiatry has not survived due to its great helping/healing capacity, but rather, due to the fact they sold out to Big Pharma and together made billions that helped buy politicians, the legal system and all the power for themselves that money can buy based on lies and fraud. Thus, this fascist psychiatry industrial complex or the therapeutic state that Dr. Szasz so brilliantly defined and exposed has nothing to do with health and everything to do with supporting the current 1% robber barons at the horrific expense of the majority subjected to the worst kinds of social control, brain/body destruction in the guise of health/help and the violation/robbery of all human, civil and constitutional rights.

http://www.evolutionnews.org/2013/05/how_a_scientifi071931.html

I don’t think it was necessary to make such a big deal of Dr. Szasz’ suicide for those of us who did not know because doing so creates the type of circus that has gone on with the death of Robin Williams while the decision to end one’s life can be based on very rational, well thought out reasons based on the pros and cons and not the so called “mental illness” the mental death profession pretends so they can impose their own form or torture/murder instead for profit and power with the pretense of concern and help. But, I think Szasz did pretty well in the media when he died and the fact his many books stay in print and keep selling shows that people brainwashed, deceived and horribly betrayed by modern biopsychiatry and its bogus, invalid stigmas and useless, poison drugs are grateful for support and validation from these noble old timers with a conscience like Dr. Szasz, Dr. Peter Breggin, Dr. Loren Mosher, Dr. Paula Caplan, Dr. Stuart Kirk, Dr. David Cohen and many others when they begin to see through this arrogant fraud. Dr. Fred Baughman, Neurologist, says all DSM stigmas voted in by consensus like ADHD and bipolar are 100% fraud to push the latest lethal, lucrative drugs and other forms of lobotomy on patent. Dr. Baughman claims that such actions by psychiatry constitute the worst medical crimes against humanity ever since children have become the major targets for this vile brain damage demolition enterprise. Psychiatry instigated the Nazi Holocaust with its horrific eugenics agenda they continue today in the guise of genetics research to blame the victims for social oppression, greed induced poverty, growing inequality, racism, sexism and many other environmental and social ills. As practice for the Holocaust psychiatry gassed to death those they stigmatized as “mentally ill” or otherwise useless eaters BEFORE Hitler came to power. In fact, Hitler praised psychiatry’s eugenics theories in his infamous book, Mein Kampf before he got involved in politics! It was psychiatry that persuaded Hitler to move the gassing apparatus from mental hospitals to the concentration camps with such “doctors” making selections for work or immediate death and even more horrific “scientific” experiments on twins like those of Mengele just as is done today in the guise of science and “mental health.” Also, psychiatry kept killing patients even after the war ended until they were forced to stop doing it openly by the Nuremburg Trials, Catholics and others opposing their psychopathy and malignant narcissism. Experts who conducted the Nuremburg Trials acknowledged that without psychiatry, the Holocaust would never have happened. So, obviously, people never learn when it comes to “snakes in suits” or demons tempting us in different guises/disguises.

So, when a dubious field like psychiatry has the whole power of a corrupt industry like Big Pharma with their billions and equally corrupt politicians and regulatory agencies with the foxes guarding the hen houses with revolving doors, I don’t think that psychiatry’s supposed success can be attributed to Szasz’ failure. Anyone challenging this Goliath is attacked and discredited viciously as a Scientologist and other garbage with tons of Big Pharma money to destroy careers and terrorize others into silence just as they do with their so called “patients” on behalf of their fellow abusers in power. Psychiatry also plays the role of enabling the outer pretense of a democracy while using the bogus DSM stigmas to attack, discredit, isolate, terrorize, institutionalize, lobotomize and all their other horrors in the guise of mental health just like Soviet Russia and other fascist states pretending to be democracies. So, when Dr. Szasz advocates for freedom while psychiatry’s role is to violate any citizen’s every individual, human, democratic civil right using their fraudulent biopsychiatry paradigm as a cover while also helping Big Pharma and others to make billions, it isn’t hard to see who would/will “win,” but I guess that depends on what one sees as “winning.” Though one may “win” in this rat race, the winner is still a rat. As Guns ‘n Roses sang, “welcome to the jungle….”

I think Dr. Szasz did win and succeed because he left his brilliant thoughts behind in his books and other work and all the lives he touched and saved like Dr. Peter Breggin, the conscience of psychiatry, with their great thoughts, compassion, wisdom and exposure of “psychiatry: the science of lies” and “toxic psychiatry” to help victims to unbrainwash themselves and become survivors/escapees of this horrific plague on humanity! Bob Whitaker’s books have been life savers for many as well as he exposed the truth about the epidemic psychiatry created rather than healing anything.

There is the story of a young boy throwing star fish back into the sea that he finds on the beach. An old man comes along and chastises him on such a futile enterprise since the boy can’t save the huge number of starfish there. The boy responds that it matters to the starfish he is able to save. The same mentality can be applied to those saved from the Holocaust or whenever a human being decides to do the decent thing rather than the evil or expedient thing. Sadly, with the decline of the best of religion, many people have never even learned the basic ethics of the golden rule and other necessities for a decent civilization. I agree with Seth Farber that there is the hijacked Constantinian Christianity and that of Jesus and his followers which is another version of the therapeutic state versus freedom, compassion, wisdom and enlightenment.

I have said elsewhere that I used to feel somewhat grateful that I wasn’t born during the Nazi Holocaust and other horrible times when in reality the fact that psychiatry sold out to Big Pharma in the 1980’s when they decided to “dance with the devil” as one APA president with lots of lucrative Big Pharma ties said to justify the destruction of so called patients makes me realize that psychiatry just continues its usual horrific crimes against humanity unabated in one guise or another whether it is state enforced witch hunts, Inquisitions and other fascist abuses just as Dr. Szasz wisely exposed, so he reminds us to beware of wolves in sheep’s clothing and other Trojan horses pretending to help during all these “times that try our souls.”

Thank you for posting here, but again, I am offended by some of your post due to my great admiration and respect for Dr. Thomas Szasz. I think you could have been a bit more sensitive and respectful of your readers and I am still not sure I get your message or overall point other than to discredit Dr. Szasz, which I think failed miserably because you are comparing apples and oranges or using a rigged system with the so called “winner” already all too well established to tolerate any competitors or critics.

I appreciate your writing here because your piece gave me much food for thought. Based on what you have added in your comments, perhaps I have misunderstood your analysis of Szasz. I agree with much of what Seth Farber says in that the power elite get to create the accepted version of the so called “truth” or “reality” they wish to prevail just like the winners get to write the history books. It doesn’t make it so!

Report comment

Donna,

I’m sorry you find the post offensive. If you read it a second time it may appear less so.

Report comment

Michael,

Perhaps if you read my post as I read yours you may see why I was/am offended by just about anything that smacks of defending the current bogus biopsychiatry paradigm that Szasz so brilliantly exposed in my opinion.

Report comment

Thank you for this. For me the issue is, do we need to spend our energy responding to this kind of thing when there’s so much more vital and concrete work to be done? I just don’t understand the agenda here, and it appears I’m not the only one, thanks for validating our emotions.

Report comment

A superb critique of psychiatry’s Big Pharma/DSM sellout by another conscientious objector!

Commentary: Against Biologic Psychiatry December 01, 1996 | Bipolar Disorder, Cultural Psychiatry, Major Depressive Disorder

By David Kaiser, MD