An extensive systematic review and qualitative meta-analysis, published open-access in Journal of Mental Health, summarizes past qualitative studies of the perspectives of people diagnosed with psychosis on their experiences using antipsychotic medication. The researchers identified four meta-themes across past studies: short-term benefits, adverse effects and coping processes, surrender and autonomy, and long-term compromise of functional recovery. Their results suggest that while people identify positive benefits of antipsychotics for acute and short-term use, they generally experience adverse effects and feel that antipsychotics compromise their long-term recovery.

“A reported challenge in psychosis is that a substantial sub-group of patients stop taking antipsychotic drugs before recommendations indicate,” the authors write. “Rather than assuming that this decision is due to denial or a lack of insight, as is often suggested, it should be explored whether such a decision results from an autonomous process in which the more experienced patient needs to negotiate the level of perceived freedom vis-à-vis his or her own psychotic experiences.”

Guidelines recommended treatment with antipsychotics for persons experiencing psychosis during the acute phase and throughout maintenance and recovery. However, while antipsychotic medications have been shown to be effective at reducing symptoms in the short term, they can bring severe side effects and challenges when used long-term, including adverse effects on cognitive functioning, reduced quality of life, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome, among others.

To improve and highlight the importance of shared decision making in healthcare, the authors of the present study sought to systematically describe and summarize the qualitative, subjective perspectives of service users regarding the use of antipsychotic drugs.

The aim of the study was to re-analyze and summarize qualitative studies on patient perspectives of using antipsychotic drugs. The search for articles was completed September, 25th 2018 and all previously published articles meeting criteria were selected for screening. To be included in the final analysis, articles had to be published in English, peer-reviewed journals, conducted with samples meeting DSM or ICD criteria for a psychotic disorder, using qualitative methods to explore the first-person experience of taking antipsychotic medication. Thirty-two articles were included in the final analysis.

Most studies (30/32) were classified as at least satisfactory in quality. Across all studies, 519 individuals were accounted for, most of which identified as Anglo-American. Participants ages ranged from ages 13-70, were 42% female, and were prescribed first- and second-generation antipsychotics.

Four themes were identified across the studies. These include: (a) short-term benefits, (b) adverse effects and coping processes, (c) surrender and autonomy, and (d) the long-term compromise of functional recovery.

Short-term Benefits:

During the acute-phase, when psychotic symptoms were severe, participants reported that antipsychotic medications were efficient in reducing their psychosis symptoms. Individuals were more comfortable committing to short-term antipsychotic treatment than long-term use.

“I’m very satisfied with the treatment I received. I got a lot of help. I felt very safe on the ward. I trusted [my psychiatrist] She was fantastic … all the staff was actually like that … . I was difficult to deal with, I must admit, I wasn’t a very easy patient. . .. I decided to use my antipsychotic medication for one or perhaps two years, then I thought I would be able to sustain myself without it. I will adhere to my doctor’s recommendation”

Adverse Effects and Coping Processes:

This theme reflects the participants’ perspectives that antipsychotic treatment came with consequences that were challenging. Despite the difficulties in finding an optimal dose that minimizes side effects while alleviating psychotic symptoms, participants mostly felt that the benefits outweighed the side effects during the acute stage. However, once psychotic symptoms dissipated, they thought that the side effects became detrimental to their mental health.

“The significance of these experiences was also emphasized in the article titles in which long-term treatment was described in terms such as ‘the least worst option,’ ‘the greater of two evils?”’ and on-going use was dependent on positive effects outweighing negative ones.’”

Significant side effects reported included functional decline, sedation, sexual dysfunction, and weight gain. These side effects were strongly associated with non-adherence to the medication.

“The medication makes me put on weight actually, reduces my motivation, changes other people’s attitudes towards me for the worse, makes me feel depressed, sometimes I’m restless, sometimes has a negative effect on my day to day living. Well just that it makes me so physically disabled, so it reduces my ability to function normally.“

Surrender and Autonomy:

Patients described participating in treatment as a feeling of surrender. Participants reported this a stressful process in which they had to trust that their prescribers were “knowledgeable and (at least) benign.” Patients did not feel involved in treatment decisions during the early stages, which lead to many adverse experiences of the patients.

Patients felt that their personal treatment preferences were disregarded, that there was a lack of trust in them from their providers, and that their personhood was repeatedly invalidated. This lead to challenges in collaboration, feelings of powerlessness, resignation, and the termination of antipsychotic treatment. In some cases, patients reported that providers would employ sanctions if the patient did not submit to their treatment.

“He told me that [unless I took the medication] I would never be able to go to a normal school … and that I would never be able to finish high school normally. And that I would never graduate. And that I needed to get used to the idea that I would be on medication for the rest of my life … that’s what he actually told me.”

During the acute/early stage when patients experience significant cognitive symptoms, they felt it was important that providers take extra effort and time to ensure that patients understood the information they shared about the antipsychotic drugs. After the acute stage, when psychotic symptoms subsided, patients felt it essential that information about the etiology of psychosis, effects and side effects of antipsychotic medications, and the expected duration of use be presented truthfully and in a manner that the layperson can understand.

In the long-term patients reported that it is “essential that communication was reciprocal, respectful, and involved a high degree of user involvement both in treatment planning and treatment delivery.” Importantly, patients preferred professionals who viewed recovery as an individual matter and who appreciated that antipsychotics are not necessarily the main ingredient in recovery. If this was not the case, resistance and non-adherence were more likely. Patients also reported using various sources to gain knowledge about their diagnosis that helped the move from “surrender to authority,” as they formed an independent opinion on the process and an increased sense of personal agency.

Long-term Compromise of Functional Recovery:

Importantly, participants perceived the use of antipsychotics as a barrier to their individual efforts and their sense of agency as they work toward recovery. Being on medication was viewed as an obstacle in being able to separate the improvements made in their recovery as coming from their own decisions and actions or the medicines. This reduced the amount of credit they gave to their own efforts. Long-term use was also associated with stigma, which leads to participants feeling that they were not suitable for social inclusion and citizenship.

“When you go out it is like advertising you have a mental illness, so the side effects draw attention to the fact that you have a mental illness. And even though you might be quite well mentally, the side effects stigmatize you…you can’t even go over to your sister’s place and go out into the yard without the neighbors thinking she’s got someone there who is mentally ill…you know your legs are going up and down all the time and they think you’re a lunatic. It’s like wearing a sign on your forehead”

Participants also reported feelings of a having to manage a balancing act between anxieties about relapse, keeping them on the medications, and worry about the long-term harm caused by the medications. Overall, this tension leads to feelings of being in a “drug labyrinth with no possibilities for escape, which gave rise to a sense of inadequacy, emotional flattering, and fear.”

“It was like the lesser of two evils . . . you can be scared and paranoid or you can have no saliva. I was going to take the no saliva but . . . it was trial and error. . . I am glad I got to the stage. . . where I actually feel like they are working.”

However, some participants had positive feelings about long-term use and reported taking steps to adapt their dosing to fit their everyday lives such as dose-reduction or manipulating the times at which they would take the medication.

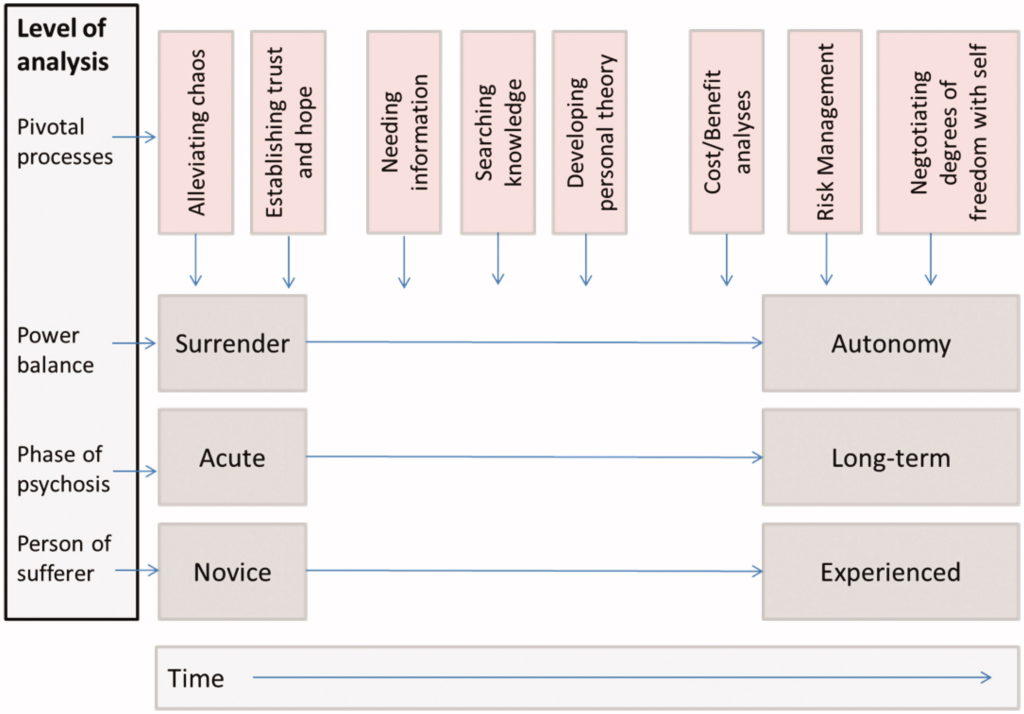

The authors of the study propose a first-person experiential model of using antipsychotic medication. Based on the analysis of the 32 reviewed studies, this model provides a developmental frame for understanding the experience of users.

Perceptions and experiences of antipsychotic use were different between for short-term acute care vs. long-term recovery-oriented perspectives. During the acute phase, the focus of the users was in their need to silence the chaos and the cost-benefit analyses and risk-management analyses became the central focus in later stages of service use.

Additionally, the process of developing autonomy followed a similar developmental path as the user developed increased knowledge and information aided in re-establishing feelings of autonomy after the initial surrender. This process allowed for the eventual re-establishment of feelings of personhood and a sense of self, which are central to the recovery process. The authors summarize that “. . . evolving knowledge, value-based opinions, and need for a sense of personal responsibility seem to constitute an overarching process.”

The authors of this study argue that the present results emphasize the importance of having the prescribing and use of antipsychotic drugs tailored to the patient’s individual symptoms, functioning, and experience. This may suggest an understanding of the decision-making process that users engage in as they decide to stop or decrease their antipsychotic use.

****

Bjornestad, J., Lavik, K. O., Davidson, L., Hjeltnes, A., Moltu, C., & Veseth, M. (2019). Antipsychotic treatment–a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of qualitative studies. Journal of Mental Health, 1-11. (Link)

“Results suggest that people identify positive benefits of antipsychotics for acute and short-term use”

Is it really a fact that antipsychotics can help people with acute psychosis? Make it shorter in time and less intense, but not longer and more intense?

Report comment

This reads largely as an advertisement for the antipsychotics, in my opinion. And positively advertising the antipsychotics isn’t what MiA used to be about. This part is true, “Patients felt that their personal treatment preferences were disregarded, that there was a lack of trust in them from their providers, and that their personhood was repeatedly invalidated.”

I will say, I’m one of the millions of people who wrongly had the adverse effects of the antidepressants misdiagnosed as “bipolar.” From the DSM-IV-TR:

“Note: Manic-like episodes that are clearly caused by somatic antidepressant treatment (e.g., medication, electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy) should not count toward a diagnosis of Bipolar I Disorder.”

So I was put on antipsychotics, even though I was not “psychotic.” But because the psychiatrists are systemically misdiagnosing the adverse effects of the antidepressants as “bipolar” (see Whitaker’s work, and this problem will only get worse, since that disclaimer was taken out of the DSM5), thus my circumstance is not uncommon.

I’d like to point out that when the psychiatrists misdiagnose the adverse and withdrawal effects of the antidepressants as “bipolar.” And then add an antipsychotic to try to “cure” this misdiagnosis, they will likely always harm the client.

Because both the antidepressants and the antipsychotics are anticholinergic drugs. And combining the anticholinergic drugs is likely to cause anticholinergic toxidrome. Anticholinergic toxidrome is a medically known way to make a person “psychotic.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

But since anticholinergic toxidrome is NOT in any DSM, thus is NOT a billable DSM disorder. It is always misdiagnosed and mistreated by the psychiatrists and doctors. And since the psychiatrist has made the client “psychotic,” to avoid mentally comprehending the harm they have done, the psychiatrists delude themselves into believing they had made a proper diagnosis.

This is a Catch 22 situation for the client. But since the primary actual function of our “mental health” industries, both historically and today, is profiteering off of covering up child abuse and rape.

https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2019/01/23/18820633.php?fbclid=IwAR2-cgZPcEvbz7yFqMuUwneIuaqGleGiOzackY4N2sPeVXolwmEga5iKxdo

https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/04/heal-for-life/

As exemplified in part by the fact that the DSM is, by design, a “bible” which requires all child abuse survivors to be misdiagnosed, in order for all “mental health” workers to be paid.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-child-does-not-have-bipolar-disorder/201402/dsm-5-and-child-neglect-and-abuse-1

It’s highly likely that these child rape covering up psychiatrists, do in reality have as a goal, Catch 22ing their clients. And since the psychiatrists’ motives are evil and illegal, this would explain why they disregard their clients’ personal treatment preferences, do not listen to or trust in what their clients say, and invalidate the personhood of their clients.

This is a synopsis of how today’s multibillion dollar, primarily child rape covering up, pedophile empowering, scientifically “invalid” “mental health” system works.

Report comment

Yes it is very pro pharma-psychiatry.

Articles like this completely ignore those of us who experience terror AND dry mouth etc thanks to taking the drugs. You complain to the quack. “How come I’m loonier than ever?’ He tells you the “meds” never ever do that and yells at you for “non compliance” though you take the drugs that mess up your thoughts and cause seizures. All you did was “pill shame” by honestly telling how they effect you.

Psychiatry is gas lighting. Pure and simple. They made me question my sanity until I totally lost it.

Report comment

You can be scared and “catastrophising” and overcome this without tranquillizers (once somebody shows you how).

Lots of people have done this before you!

Report comment

The main goal of psychiatry was to build the proper image of the psyche, not to get rid of the psyche. Drugs were to help in dealing with psychosis, not to destroy the essence of psychosis.

Psychiatry is the biggest enemy of the psyche. They hate everything that is not material and does not involve making money. Because it is a calculating soulless child of lies and mammon. Psychiatry have destroyed the essence of the psyche.

They are not intrested in the reality of the psyche, they can’t see the need or psychological value of psychosis or depression. For them psyche is just pure evil. They just want to destroy it in the name of theological or materialistic negation.Sometimes when I think about differences between psyche and the coarse reality of apollonic/spiritual negation I wonder when this all will collapse. Because they have gone too far with destroying the proper image of psychological reality.

Why, you, authoritarians,hate psyche so much? Because of fear? Or because non material reality is still satan for you?

Report comment

And of course the idea of Recovery, is simply classifying people who have nothing wrong with them as lab rats. Any involvement in giving out such drugs, or even writing an article about it, is medical abuse.

And then “participants reported that antipsychotic medications were efficient in reducing their psychosis symptoms.”

Again, classifying people who are angry or in distress as having some kind of an illness.

Report comment

I hate antipsychotics. Been on them for seven years. Poison. Now they give them to babies

Report comment

They are a doddle to come off. What isn’t a doddle is trying to live with schizophrenia. Of course some people never had schizophrenia in the first place and so when they tell you how easy it is to live with schizophrenia are really pulling the wool over their own eyes. They haven’t got a clue.

Under the line here schizophrenia doesn’t exist. It’s a nothing.

But text is cheap.

Out here in the real world schizophrenia is like living in a one-person war-zone every day of your life.

Not everyone wants to live in a war zone every day of their life.

They just can’t handle it or don’t want to handle it.

There are lots of people that never had schizophrenia, that had some kind of blip and were misunderstood, and got treated really badly. I feel sorry for them but I have no sympathy for their lack of understanding of schizophrenia and its true sufferers. They do the true sufferers of schizophrenia a terrible injustice.

Having said that… 7 years away from the war zone is surely long enough to consider going back and seeing if you can handle the fight?n

Report comment

rasselas,

Nice to see you again.

Living in the real world might very frightening for lots of people that don’t at all have “schizophrenia”.

Report comment

That’s true, Fiachra but I wasn’t focusing on the feelings so much as the effects of living in a kind of virtual war-zone. Which can be frightening and thrilling all at once, sustainedly stressful in ways that impact a person’s life in unparalleled ways.

In others words, the experience and impact of The Fear upon the person with schizophrenia will be remarkably unalike how fear impacts the general population, even in an actual war-zone.

This is why people with schizophrenia have been afforded disability status and concomitant disability rights. It would be uncivilised for society to dismiss the impact of schizophrenia on a person, and thus deny disability rights, and I for one will always push back against any attempts to do so.

Report comment

While this study gets a very broad view of the effects correct for many, it stops & pats itself on the back when summarizing…..ridiculous considering the ubiquitnous of the data that has been available in any community clinic or private practice for decades.

Many would prefer to read about ‘the Fix’; stop prescribing any drug unless it’s SAFE.

As it stands, that would be NEVER for what’s defined as ‘mental illness’….but some folks want that option.

Overstating the obvious, bloodjessly discussing the need for responsible prescribing & expecting applause from the exploited and damaged is naive.

As this represents some kind of scientific epiphany and insight is ridiculous and offensive.

Report comment

Yep. Captain Obvious to the rescue! 😀

Report comment