In 2011, I had the privilege of joining the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to launch a national program to provide outreach, screening, and treatment services for veterans with depression, post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and other mental health needs. These efforts became a passion for me because during my three years as the president of Student Veterans of America (SVA), we lost some student veterans to suicide. When I received the first notification of a suicide, I felt like a commander who’d lost an airman but didn’t have the resources to stop it from happening again.

At the time, I’d viewed the VA as the consummate experts in the area of veteran mental health and suicide prevention, and felt my job offered the best opportunity to make an impact.

A few years later found me working in New York City as a tech entrepreneur. It was here that I climbed onto the train I’d previously been working to drive: I became a patient in a veteran mental health program.

It was the spring of 2015, and I’d been distracted from the pre-MBA classes I’d been taking at Fordham University due to the tech company I was starting. This led to my being prescribed the stimulant Adderall by a private-sector psychiatrist. A year later, I sought treatment at the VA. Over the next four years, VA doctors prescribed me thousands of pills, at times six different medications at once. Nearly all of them were central nervous system (CNS) drugs or prescribed to treat the side effects of those drugs.

During that time, my life fell apart to the point where many, including me, believed I would never recover. Today, I am completely off the prescribed cocktail I’d been on. Although the journey included a year of immense physical and psychological pain as I withdrew from the antidepressant Zoloft, I survived it.

On November 10, 2019, I co-published a report with journalist Robert Whitaker detailing VA suicide data showing an increased risk of suicide for veterans treated at the VA. The report also documents disproportionately high rates of psychiatric drug prescribing to veterans; many of these drugs are known to increase suicide risk.

I remain a patient of the VA for my regular healthcare, as I have a new goal in life: to help the Department provide the level of care our veterans deserve, and in so doing prompt an inquiry into the drugging of veterans at the VA and its link to the national epidemic of suicides in the military and veteran communities.

That is why I have decided to share my story of treatment at the VA. It may not be every veteran’s story, but it’s a reality for far too many of us.

Growing Up “Up North”

I’m from Alanson, Michigan, which lies within a larger resort area in the northern part of the state. I didn’t grow up in the resort, but rather outside of it, and helped to work it just as my family has done since my European ancestors first homesteaded there in the 1870s. There are those who have summer cottages and spend their weekends “Up North,” as visitors proudly call it, and then there are those who log its hills, excavate its gravel, and fight the wars. I was part of the latter group.

As a kid, I never felt we needed for anything, but I was also aware that we worked for everything we had. There wasn’t any excess. My dad labored for his father — who fought in World War II at Normandy, Ardennes and the Battle of the Bulge with the 820th Tank Destroyer Battalion— and alongside his brothers, two of whom would serve in Vietnam. My mom worked the 3:30 a.m. preload shift at UPS. Her own father had served as a Navy radioman in the Pacific during World War II and all four of her brothers served in the military either during or in Vietnam.

When my grandfather returned from war, he married my grandmother, the daughter of a World War I veteran. Together, they bought land not far from the original family homestead in rural northern Michigan and started a small excavating business. My grandmother ran the books. Their kids worked the family business.

My brother and I would fly like airplanes through the rolling hills of northern Michigan as we rode in the rusty box of my dad’s early-1980s Ford F-150 to reach a relatives’ property to help our parents cut and split firewood for the winter.

Most mornings, my dad took my younger brother and me to school. Growing up, I was never fast to rise. On mornings when I wasn’t moving as quickly as my dad felt appropriate, which was always an hour or two earlier than my classmates, I was properly motivated with a pan of ice water enveloping my face.

In the summer of 1998, between my junior and senior years of high school, I began working for the family excavating business. That summer, I sat inside the steel cab of a front-end loader in the bottom of a gravel pit, baking in the August sun. During those months, I forgot about the snow entirely, and for brief periods, dreamed of it. I learned to operate a dump truck, loader, backhoe and hand shovel; I was following the career path of most of my cousins, uncles, and my dad.

A few months later, two of my classmates told me that they were going into the Air Force. They said I should join them, so I met with the local recruiter.

Aim High

In October of 1999, the fall after my high school graduation, I enlisted in the United States Air Force. I was assigned to the AC-130H Spectre Gunships as an aircraft electrical and environmental systems technician with the 16th Special Operations Wing at Hurlburt Field, Florida. This was the headquarters of the Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC).

The AFSOC motto — “Any Place, Any Time, Anywhere” — permeated our unit culture. What made our planes and our mission different from those of other Air Force units wasn’t our planes’ 105mm howitzers, which used to be on tanks, or the 40mm cannons that used to be on ships. Rather, it was our customers. Our primary mission was supporting Special Forces operators around the globe.

On September 11, 2001, at close to 9 a.m., I was still in bed. I’d worked the swing shift, from 3 p.m. to 11 p.m., the night before. One of my roommates came into my bedroom and said, “You’ve gotta see this, a plane just hit one of the Trade Center Towers in New York.” By the time I made it into the living room, the second tower had been hit.

I’d been to the top of the Trade Centers two and a half years earlier during my high school senior trip to New York City, one of the few times I left northern Michigan growing up. As I marveled at the incredible feats of human ingenuity in the seemingly endless landscape of steel, brick and concrete and considered my limited options after high school, I thought, “Derek, you better soak this in. You’re never coming back.”

I began gagging as tears began to fall down my face as I thought about the people in the buildings.

My friend and I quickly put on our uniforms, got into his Mustang, and drove to base. We wanted to know where we were going to be sent. On Thanksgiving Day, we departed Hurlburt Field en route to Uzbekistan as the U.S. launched the war in Afghanistan. This would be my first of three deployments: two to Uzbekistan and a third to Afghanistan in 2005.

I was incredibly fortunate not only to be part of America’s response to 9/11, but also to remain safe throughout my time overseas. In Afghanistan, my unit was occasionally on the receiving end of rocket attacks, which at times drove us into concrete bunkers. Once, a rocket exploded about 100 to 200 yards away from our living quarters, hitting a truck and a few small buildings, but no one was hurt. We knew the rocket attacks were poorly aimed, and so I never really felt in danger.

Many others weren’t so lucky. I lost a friend who deployed to Iraq in 2005. I’d seen him just a few weeks earlier in Afghanistan. We were supposed to get drinks when we got back to our base in Florida.

In 2005, I transitioned into the Michigan Air National Guard, moved back to northern Michigan, and began classes at my local community college. A year later, I was accepted to the University of Michigan. When I matriculated on January 5th, 2007 — the same day U.S. Senator Jim Webb introduced the Post 9/11 GI Bill into the Senate — I began studies in psychology, as I wanted to work with soldiers and other vets to recover from war trauma. While at Michigan, I felt isolated: As a non-traditional, first generation, working class, 26-year-old military veteran, I didn’t have much in common with my classmates. It was from this transition that I got the idea to start a student veteran group on campus.

At the same time the Student Veterans Association at the University of Michigan started to come together, I began working with other veterans from around the country to start a national student veterans organization. Together in Chicago in January of 2008, we founded Student Veterans of America (SVA). The week prior, I’d bought my first suit.

Three weeks after SVA’s founding, I found myself in Washington, meeting with then-United States Senators Jim Webb and Chuck Hagel. Over the next several months, I traveled to Washington seven times to lobby for the passage of the bill while working with student veterans in congressional districts across the country.

On June 19, 2008, the Post 9/11 GI Bill passed through the House. A week later, it was passed in the Senate, and on June 30 President George W. Bush signed it into law. Senator Webb, the bill’s author, later said of SVA’s efforts on behalf of the bill: “Student Veterans of America has played a powerful voice in shaping the debate in Congress for a reformed GI Bill.” I had just turned 27.

The Expert Patient

Not long after, I visited the VA headquarters in Washington, D.C. to meet with a woman who would become the VA’s chief of the Office of Mental Health Services (now the Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention). The meeting was in my former capacity as the president of SVA, which has gone on to host over 1,500 chapters in four countries and represents over 750,000 student veterans.

Entering the meeting, I was skeptical, even bitter. The woman I was meeting with was filling in for Dr. Ira Katz, who was unavailable due to a scandal that had been plaguing him and the Department since the fall of 2007. That was when CBS News had run an exposé titled Suicide Epidemic Among Veterans, which first exposed the growing veteran suicide epidemic. Until this story ran, the VA had not tracked veteran suicides nationally.

CBS ran a follow-up story when the VA pushed back on the report, arguing that the broadcast was “not reviewed by independent scientists as most legitimate studies are.” Next, Congress and the media accused Katz and the VA of covering up veteran suicides at the VA. A Freedom of Information Act request had revealed internal VA emails from Katz with the subject line “Shh!”, in which he wrote that the suicides were “something we should (carefully) address… Before someone stumbles on it.”

So to my surprise, the woman I met with did not seem to be the villain I was expecting. She was kind, empathetic, competent, and honest. She would also soon make history in the organization as the first psychologist to serve as the VA’s chief of mental health. Until her appointment, only psychiatrists and medical doctors had served in that role.

A few years later, she contacted me and asked if I would be interested in joining her at the VA. The role entailed building a new national mental health program for veterans on college and university campuses as part of former VA Secretary Eric Shinseki’s “21st Century Transformation Initiatives.”

I had reservations. I’d worked with the VA in the past and had not liked much of what I saw. The 330,000+-person bureaucracy did not appeal to me, nor did getting lied to to my face, as I’d experienced firsthand from senior VA officials in prior years. However, after conversations with friends and mentors, I came to believe that Secretary Shinseki, whom I already respected deeply along with the mental health chief and her team, sought the long-term cultural change the organization needed. Based upon those factors — and thinking I might be well-positioned to help veterans — I accepted the role.

As I began engaging with social workers and psychologists at VA Medical Centers across the country, I was again surprised. Their passion for and dedication to helping veterans was unparalleled. Not only did they endure their local bureaucracies and seemingly unmanageable caseloads, but also had to hear daily horror stories of combat and military sexual trauma from their patients. It was all part of their daily counseling responsibilities in helping our nations’ veterans through their recovery.

“Pink mist” was a term they learned and heard regularly. (When someone is shot or blown up, their blood spatters into what can best be described as a pink mist in the air.) They listened to the firsthand accounts of veterans losing limbs, watching their friends die in their arms, and what many veterans feel to be the worst trauma of all, surviving when their friends did not.

At the VA, I came to realize I was working with some of the most compassionate, caring, and incredible human beings on the planet. Along with these amazing people, I had the privilege of building the Veterans Integration to Academic Leadership Initiative (VITAL), which I branded with a focus on empowering veterans rather than approaching them as broken toys. As of last year, the program had enrolled 9,000 veterans from 144 colleges into VA care at 24 VA medical centers and provided over 42,000 therapy appointments.

Never did I question, nor do I believe any of my colleagues ever questioned, that our efforts could unintentionally cause harm.

A Student Veteran, Again

By the spring of 2014, I was three weeks into a compressed course load at Fordham’s pre-MBA program and I’d barely opened a book. My first calculus exam was a week away. I was on track to fail the classes, which I’d taken with the goal of strengthening my application to Harvard Business School (HBS).

Struggling to figure out why I couldn’t focus, I recalled that I’d been diagnosed with attention deficit disorder (ADD) in the eighth grade. For years, I felt I had been misdiagnosed and that my academic distractions came from the severe bullying I’d received, all for just being a goofy kid. But maybe I was wrong. Maybe I did have a disorder, and maybe it was time to treat it?

The First Drug Deal

As one might expect, the walls of the psychiatrist’s office I visited featured framed degrees. This one featured Cornell Medical School and Yale. The certificates had their intended effect: They made me feel more confident in my decision to pursue this path.

But as I sat down, I didn’t feel as comforted as I thought I should in meeting with a mental health clinician. Instead, the environment felt transactional, corporatesque. To complement the listlessness of the decor, the psychiatrist’s desk was cluttered with billing statements and invoices.

The conversation began quickly and frankly. He asked why I was there. I told him my academic situation and that I had been diagnosed with ADD as a kid. A few minutes later he wrote me a prescription. Then he asked for $350.

Twenty minutes, $350 (in cash), plus the cost of the Adderall prescription at the pharmacy later, I was handed a drug that sits a molecule away from methamphetamine.

I got an A in calculus. Unfortunately, I also stayed on Adderall, as the psychiatrist and I felt the drug was helping me with my “disorder.”

A month later, I was recruited for a demanding, six-figure job at a level I could have expected after graduating from HBS. When I told the prescriber I hadn’t been sleeping, he looked at my chart. He connected the Adderall with my insomnia. Ambien was added to my drug regimen.

Less than a year after I joined the company, it developed cash flow issues. I was laid off. In a twelve-month period, more than a third of the company turned over. When I started looking for my next steps, a close friend pushed me to start the technology company I had been working on the year before.

From there I set out on my path as a full-time tech startup entrepreneur, following the paths of Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Elon Musk. A few months later, I discovered I was eligible to use the VA for my healthcare.

Entering the System — Manhattan VA Medical Center

At my intake with the VA doctor, they wrote:

29 July 2015

“Male, white, 34 year old, Air Force and Air Force Reserves veteran, served 12 years in the military, honorable discharge, college graduate with a double major in Psych and Political Science. Veteran recently found out that he could get service at the VA. Veteran is seeking treatment for his ADHD, which he was diagnosed when he was in 8th grade. Veteran stated he was given Ritalin then “but it made me feel like a robot.” Veteran has his own firm; he’s the CEO of his firm. Veteran initiated the Student Veterans of America in 2008. Veteran stated that he comes from good upbringing in Michigan. Veteran reported to have been bullied from 3rd grade to 12th grade. “I was bullied a lot in school.” He is apparently diagnosed with ADHD and takes Adderall 10 mg and also Ambien 10mg for insomnia and he apparently has anxiety and depression as well.”

During this appointment, I received my first prescription from a psychiatrist at the Manhattan VA. The next month, I was back. This time the psychiatrist wrote: “He described anxiety sx: worried about a lot of things, feels restless, has whole body tightness and stress tension between temples. Currently he describes his anxiety as 7/10.”

To help me manage the stress from starting my company combined with the anxiety-inducing effects of the Adderall, the doctor prescribed Gabapentin in addition to the Ambien I was already taking. (Gabapentin is commonly prescribed off-label as a mood stabilizer for anxiety disorders.)

At my next visit to the psychiatrist, he increased my Adderall prescription to 40 mg a day. We’d learned the generic Adderall the VA prescribes seemed to have less strength than the brand-name drug I’d been on, while offering all the same side effects.

A month later, the psychiatrist switched me from the generic Adderall to the brand name drug, but this time to the extended release (XR) version. If you’ve never taken Adderall XR, imagine drinking 50 cups of coffee in a workday. It caused me such anxiety that I developed a vice-like pressure on my temples that made me want to grind my teeth apart. The feeling lasted seven to 12 hours.

Again, my dosage was changed, and I was switched back from Adderall XR to the generic, immediate-release version.

Around this time, my company was accepted into a technology incubator program, part of New York University’s (NYU) Tandon School of Engineering, and now called the Veterans Future Lab. Shortly after that, my business partners and I raised $150,000 to get the company off the ground. We were focused on creating a portable door sensor that could detect break-ins to a hotel room, or any other room that the user wanted secured.

Wash, Rinse, Repeat

An average day for me now looked like this:

5:30 a.m.: I’d start the day with a 20 milligram Adderall to get me moving for my 6 a.m. Soul Cycle class in the West Village. Then I’d shower at the gym and walk to my office at the NYU Future Lab in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood. Throughout the morning, I’d work on investor presentations, review product designs, and check product development status over video conference with my co-founder based in Denver.

12 p.m.: I’d take another 20 mg Adderall. Later in the day, I’d take a Gabapentin to take the edge off the anxiety-causing effects of the stimulant.

1 p.m.-4 p.m.: Investor and partner calls, all while trying to calm myself down enough that I didn’t come off as too intense.

3 p.m.-4 p.m.: I’d occasionally take a quarter of an Adderall pill (5 mg) to keep going. I’d then work until 8 p.m. or 9 p.m.

10 p.m.-midnight: I’d take an Ambien to knock myself out.

And I’d do it all over again throughout the week. I told myself it was working. It wasn’t.

It’s on Fire. All of it. Burning.

Within the year, the company was burning. I’d overestimated how long we could stretch our funding and underestimated product development times. I can’t blame it all on the drugs. At that point the accumulation of failures was catastrophic. Of course, Adderall, Ambien, and Gabapentin weren’t exactly helping.

I held the break-up video conference with my team. Through tears, we thanked each other for the hard work and for having become a tight-knit family. When the meeting ended, I was in a daze. Beyond the failure, I didn’t have a plan. I hadn’t built a parachute for “if” the company failed, because I hadn’t ever suffered a real failure before.

Luckily, I landed a consulting project for the Bob Woodruff Foundation. I’d helped to set up the partnership between the Foundation and SVA years earlier, which led to one of SVA’s first major grants, and I’d maintained relationships within the Foundation over the years.

Unfortunately, I was past the point of burnout. The stress twitch I occasionally had in my left eye while running the company returned. Now more aggressively.

On August 15, 2016 at 1:30 p.m., I felt my heart racing out of control. The eye twitch wouldn’t stop. Two new twitches in my arm and chest developed. I started losing my breath. Coinciding with dizzy spells, my vision started to fade in and out. I quietly packed my bag, then walked the 20 blocks from the Foundation’s office in Herald Square to the emergency room at the Manhattan VA Medical Center at 23rd Street and 1st Avenue.

At the ER, I was told I was having a panic attack. For the first time in nearly three years, my Adderall prescription was suspended. Klonopin, or Clonazepam — a benzodiazepine — took its place daily for a month or two.

A few weeks later I returned to the VA for a physical. At some point, I pointed to a bald spot forming on the back of my head and asked, “Anything I can do about this?” The resident said “sure.” He got approval from a physician and they prescribed me finasteride (Propecia), which I later learned was against VA policies to prescribe for cosmetic use.

Within a few months of starting on finasteride, my cognitive functioning began to decline. Putting together coherent thoughts became difficult. The Woodruff Foundation contract ended. At my next psychiatrist visit in December 2016, I was again switched off of Adderall, which I’d been re-prescribed weeks after the ER visit for the panic attack. In its place, I was prescribed Ritalin.

In January, I returned for what would be my last psychiatry appointment at the Manhattan VA. I was put back on Adderall because we felt the Ritalin was causing intolerable side effects. My cognitive decline was spiraling, faster now. With the confusion I was experiencing, the stimulant was like pouring gasoline into a fire.

I could no longer survive in New York and needed to get back to Michigan, closer to family. When I tried to pack my apartment, I found myself confused and anxiety ridden. I couldn’t even pack a box. I called a close friend from my time in the NYU program and she and her boyfriend came uptown and packed my apartment for me. I could do little more than watch as my life was placed into boxes.

Another friend rented a U-Haul, and together the two of us drove back to Michigan. During the ride back, I felt ashamed, mostly for having failed my way out of New York.

The Train Wreck Arrives at Ann Arbor

Returning to Michigan, I was again rescued by friends. One lent me an extra vehicle and gave me an office at his company where I could work on the consulting projects I’d miraculously managed to acquire. The circumstances leading me back to Michigan hadn’t been good, but I now had a roof over my head, a vehicle for the time being, and an office with friends around me. I had everything but my mind, which was still in decline.

When I tried to get my medications renewed at the Ann Arbor VA, my new psychiatrist renewed the Adderall, Ambien, and Gabapentin without comment. Surprisingly, when I called my new general practitioner (GP), she refused to refill the finasteride. She said it was against the VA’s formulary and was confused about why I was prescribed the drug in the first place, as she could find nothing in my records explaining why I was on it.

Confounding everything else, I now struggled to get out of bed and didn’t have the energy to get through the days (even with taking 40 mg of Adderall daily). In my first meeting with my GP, she wrote:

“Recently moved back to Michigan from NYC. Fatigue/low energy — wants to know why. Denies current depressive symptoms. — Needs baseline labs, particularly given use of medications. He also requests labs to investigate cause of fatigue, including testosterone. Lab tests all came back good.”

When I met with the psychiatrist in April, he added this to my records:

“Patient says: ‘something is wrong.’”

It was. I struggled to put sentences together. At times, my thoughts came out like a word salad. I was terrified that I might have brain cancer. Noting my symptoms of depression and anxiety, he said: “How about we try an antidepressant?”

I was prescribed Zoloft (Sertraline) at 100 mg a day. By this point, I was breaking down, unable to advocate for myself and make sound decisions. Not that it would have mattered. I trusted the psychiatrist. He’s a doctor.

A few weeks later, the psychiatrist wrote:

“I would not recommend Finasteride for psychiatric use.” and “associations found between Finasteride and psychiatric complications including depression and suicidal thoughts. When seen 4/17 had notably increased anxiety and depression.”

On May 15, 2017, a month after being first prescribed Zoloft, my general practitioner annotated the following in my record:

“Here to follow up on energy, use of Finasteride, concentration. — Finasteride prescribed September 7 2016. Relates that symptoms of fatigue started in fall (not exactly sure timing relative to Finasteride) (feelings like you don’t want to get out of bed…. symptoms kept on worsening). In March symptoms “got really worse.” And “Energy crashed (also around time he stopped taking Finasteride). 2 months now without Finasteride. Calf pain somewhat better but not completely. The long term effects (after stopping) Finasteride remain unclear.”

At this point, it was clear finasteride was the likely cause of my psychiatric complications and depression, but sadly, this fact wasn’t reflected in my treatment plan. The Zoloft prescription was continued.

Around this time, I became familiar with the term “Post–Finasteride Syndrome.” It was also in this medical note where my leg pain was first recorded. This note would be important later as I began to withdraw from Zoloft.

My latest consulting projects ended, one for a technology company and another for a global auto supplier. For the latter company, I was tasked with developing a global startup technology investment strategy for the German-based firm. Even with my reduced ability to function, everyone believed I was still me.

By the time the contracts ended, though, I was non-functional and unemployable. The combination of the Post-Finasteride Syndrome and the life-numbing effect of Zoloft led me to believe the best I could ever do again would be mowing my parents’ lawn. By then, I was living in their basement.

I began to accept that I might have a permanent disability and began thinking through the logistics of making a new life as a disabled person work. I thought, “Will I just live in my parents’ basement for the rest of my life? Doing chores could help offset my burden, but how do I make money to subsist?”

This entire period confounded those close to me, no one more than myself. Today I look back on this time with profound sadness, as I had lost my ability to think and care for myself.

A Second Chance and a False Start

One day out of the blue, the auto supplier I’d consulted for called me. They needed someone with leadership skills to help them work through production delays. It was around this time that I started to get some of my energy back, the result of the finasteride finally working its way out of my body. I was brought into the company, treated like a part of their team, and trusted to help them navigate the supply chain challenges they were experiencing.

I was back! I didn’t need the antidepressant. I was no longer depressed!

On September 27, 2017, I called my psychiatrist — it had been four months since I’d last seen him. I simply needed to get my Adderall, Ambien, and Gabapentin refilled. During the 15-minute call, I informed him that I had stopped taking Zoloft and that I was doing great! I could hear the concern in his voice, but he didn’t explain why. I didn’t think much of it, but I’ll never forget it, as it seemed very odd.

While I thought I was doing “great!”, I was actually manic from antidepressant withdrawal. This was something I was unaware of, as I’d never heard of antidepressant withdrawal before. I would later learn that withdrawal can cause agitation, paranoia, physical pain, and other symptoms.

On October 13, a little more than two weeks later, my psychiatrist updated my records:

“Pt phoned, asks about restarting sertraline. Lost job last week. Currently staying at his parents.”

He renewed my prescription over the phone. It had been four months since I’d seen him last; I wouldn’t see him again for another four months. All the while my psychiatric medication was renewed and mailed to me.

I was back to being unemployable again. The antidepressant seemingly muted my ability to care about anything. I didn’t care about getting out of bed, about getting a job or even about feeding myself — so much that for the first time in my life, I stopped shaving and grew a beard. I also met with my GP, as my foot and leg pain had inexplicably worsened. She wrote: “Toe pain — R big toe numbness for half a year or so. Also a little in L toe. — Being treated for ADHD and depression.”

I was back to being unemployable again. The antidepressant seemingly muted my ability to care about anything. I didn’t care about getting out of bed, about getting a job or even about feeding myself — so much that for the first time in my life, I stopped shaving and grew a beard. I also met with my GP, as my foot and leg pain had inexplicably worsened. She wrote: “Toe pain — R big toe numbness for half a year or so. Also a little in L toe. — Being treated for ADHD and depression.”

By this time, my body had finally gotten used to the Zoloft again, and I was starting to become semi-functional. I found the energy to piece together a data story based on my market research on the mobility and artificial intelligence sectors from my work for the auto supplier earlier in the summer.

I decided to move back to the Ann Arbor area to try to get a job, and began living with a close friend, his wife, and their two young children. After meeting with a few of my old mentors and professors and sharing some of my findings with them, we formed a working group of University of Michigan senior leaders, professors, students, and alumni and began investigating the impacts of technology on the workforce and society.

On January 29, 2018, I finally met with my psychiatrist for the first time in eight months. He wrote in my file:

“He has been living with friends who have 2 small children and this is going fine. Has not worked formally since October.”

He added Generalized Anxiety Disorder to my growing list of diagnoses and increased my Zoloft prescription from 100mg to 150mg. This was in combination with the 40 milligrams of Adderall, 300 milligrams of Gabapentin, and 10 milligrams of Ambien I was already on.

Things weren’t “going fine.” I was still unemployed. While I split and stacked firewood and helped with my friends’ kids, who were now calling me “Ujo” (Slovak for uncle), I wasn’t paying rent.

I still don’t like saying it, but whether it was an AirBnB or a friend’s couch that kept a roof over my head, the fact was that I was homeless. And it was like that off and on for close to a year. The psychiatrist noted that I was interested in pursuing video teletherapy. I wasn’t. I had been asking to see a counselor but VA policies required that I go through a month-long group program first, which I was not comfortable with, so I was denied. As a result, teletherapy was all that I was allowed to do. I didn’t need a computer screen. I needed a person to help me figure out what was wrong with me.

I had the support of my friend and his beautiful family, but I felt so very alone.

The higher dose of Zoloft affected me terribly. I spent the next few weeks in bed. During the next few months I was nearly immobilized, and again lost all motivation to care for myself. The technology and society working group I had put together at the university never met again.

In mid-February, I met with my GP. I had come to trust her, as I could see that she had been fighting unsuccessfully to get me in to see a counselor. I felt she saw what I knew: The person we were looking at wasn’t me.

This time, she tried to get me in to see primary care mental health, but since I was already enrolled in the VA’s formal mental health system, VA policies wouldn’t allow it. Again we discussed my foot pain and toe numbness. With all of the tests she ran, we still weren’t getting any answers.

In early March, I received a call from the same friend who had lent me a vehicle and an office the year before, asking if I would go to work for him. He’d seen how much of a mess I was, but he’d mentored me a decade earlier when we’d first started SVA and he too knew that the man I’d become wasn’t me. That, and he prided himself on investing in undervalued assets. At this point, he was buying at the bottom of the market.

The Epiphany that Saved my Life

A few weeks later, after finally holding a job for the first time in six months, I was talking with a friend. She volunteered that her antidepressants were being increased. That she was on medication surprised me, so the only appropriate question I could think of was, “How is your counseling going?”

She shared that she wasn’t seeing anyone because her insurance didn’t cover it. I was shocked. During my time working at the VA, I would have been outraged if I had learned that a psychiatrist working as part of my program was prescribing psychiatric medications and the veteran wasn’t getting counseling. Drugging someone is not treatment.

It wasn’t until the next night that I asked myself: “How many drugs am I on? When was the last time I saw a counselor?”

Through the fog of meds, I used my fingers to count the number of drugs I was taking. When I hit my second hand and my sixth finger, I was in shock. Then I tried to recall the last time I’d seen a counselor at the VA.

I’d been using the VA for nearly three years at that point. I’d been prescribed nine different drugs. During those three years, I’d never had a single session with a counselor or psychologist.

I no longer trusted my psychiatrist. When I’d arrived at the Ann Arbor VA from New York City, I’d been unable to advocate for myself. When I did occasionally question the cocktail I was on, I pushed the thought out of my head. I figured, “He went to medical school, he knows what he’s doing.”

Withdrawal

I started taking myself off the drugs over the course of three to four weeks. After nearly four years of taking Adderall and Ambien daily, as prescribed, and Gabapentin as needed, I had no issues with stopping.

When I started withdrawing from Zoloft, which I’d only been taking for a year, I started having terrible withdrawal symptoms. My ears started droning with pressure as though my head would explode (the same feeling you get when driving down the interstate at 70 miles an hour with the back windows down). I started to have brain zaps, which coincided with blank spots where brief blips of time disappeared. I was so dizzy and nauseated I could barely stand without nearly getting sick.

As all of this was happening, a social worker friend sent me an article that ran in the New York Times the day before: “Many People Taking Antidepressants Discover they Cannot Quit.” Reading the article, I realized I was going through acute antidepressant withdrawal, I took a half-dose and all my symptoms immediately vanished.

Two days later, on April 9, 2018, I went to my GP without an appointment. I was still traumatized by the acute withdrawal event. My doctor wrote:

“Walks in this afternoon to be seen urgently. Decided that medications are making him worse, not better. Started working out, got a job, decided he is feeling better and wants to get off meds. Then he started to cut down on sertraline from 150mg to 100mg to 50 mg. Then quit it, went from 50 mg to off and then got severe physiological symptoms — tremor, nausea, tinnitus and pulsation, agitation. The pt feels he has been overtreated for years and wants to get off of the meds. Pt was not aware until recently of the rebound potential and the physiologic “withdrawal” symptoms. Of note, he still would like to see a psychologist/therapist. He is frustrated that he needs to see a video therapist when he is living in AA, and he does not want to go to group therapy. He requests that we attempt again to have him see a psychologist or SW. Alerting [name redacted psychiatrist] to this request.”

I learned the hard way that once on an antidepressant, you can be trapped on the drug for years — and for some people, permanently. During my withdrawal, I experienced bouts of rage and felt as though I were being fed gunpowder. Walking down the street, I hoped someone would look at me wrong so I could get into a fight. (Which was unlike me, as I’ve never been violent.) I became paranoid to the point that I believed I was being followed and that my phones were tapped, and I had nightmares I cannot forget.

The physical pain was as bad, and at times worse than the psychological pain. During this period, I was doing physical labor, working as a mover. I didn’t know it, but the terrible daily physical pain I was experiencing in my muscles and joints, especially in my feet and legs, were being caused not by exertion but by the antidepressant.

I went back to the psychiatrist for what I thought would be the last time, but I didn’t receive much help. His version of supportive therapy didn’t feel incredibly supportive:

“Gave feedback what he is experiencing is highly unusual,” the psychiatrist wrote, and “He decided not to pursue tele-health therapy. Continues to resent the requirement of Treatment Planning Class [group therapy] and not asking to pursue additional therapy today.”

Through the articles I found on the Mad in America website, I learned a new term. I was “iatrogenically harmed” (injured by medical treatment) and was suffering from protracted antidepressant withdrawal. Still, because of VA policies, I still wasn’t allowed to see a counselor. (I now believe some of these policies are in place to deliberately delay access to treatment, thereby protecting the VA facility’s performance metrics, a more sophisticated manipulation of appointment times than what happened at the Phoenix VA and other VA medical centers in 2013.)

When I tried to get the VA to submit an adverse drug reaction report, I found myself having to explain to the psychiatrist what exactly I was asking. I told him I wanted it reported, as I wrongly assumed that every time a veteran has a bad reaction to a drug, it is recorded in a centralized system, through which VA leadership can identify medications which might be harming their patients. (The system does exist, but isn’t used as VA policies dictate.) I just wanted to make sure that what happened to me didn’t happen to anyone else.

It took me an entire year to get off Zoloft. The psychological pain, isolation, physical pain, and injuries I incurred as part of withdrawal were debilitating. Most doctors and psychiatrists are largely unaware of the severity of the side effects of antidepressants or the extreme dangers associated with withdrawal, and most patients at the VA are not adequately informed of the risks of these medications. It wasn’t until at least six months into my withdrawal that my own psychiatrist started to believe some of the symptoms I was experiencing. (I detailed my full withdrawal story in a blog, “Ambushed by Antidepressant Withdrawal.”)

Treatment Summary and Supportive Therapy

A year ago, an old clinician friend who ran national veteran mental health programs for the University of Michigan asked me, nearly in tears, “Derek, you’re not a layperson, how did this happen to you?” Without hesitation, I replied, “It was the drugs.”

Since that conversation, I’ve had time to further research the drugs and psychiatric medications that harmed me and to better understand what happened. “It was the drugs” encompasses 80% of the problems I experienced. But I’ve been forced to recognize there is more to the issue than just the drugs.

In four years of treatment at the Department of Veterans Affairs, I was prescribed thousands of pills. At times, six different medications at once. With the exception of the finasteride, all of the drugs were prescribed as a result of the original misdiagnosis of ADHD, or to counter the side effects of other drugs.

In those four years I never had a single therapy session with a VA psychologist or counselor.

And in four years of treatment, I’d received a total of five hours of “supportive therapy” from my prescribing psychiatrists. This averages out to just over an hour of supportive therapy annually.

The supportive therapy I received from my psychiatrist visits at the Manhattan VA averaged 15.625 minutes over the course of nine appointments in 1.5 years. At the Ann Arbor VA Medical Center, the average amount of supportive therapy I received from my prescribing psychiatrist was 15.7 minutes. Seven sessions over 2.5 years.

For two of those years, I lived with the constant thought of death. It is fascinating that I am alive to write this.

In Ann Arbor I went eight months without seeing my prescribing psychiatrist, all while being prescribed multiple psychoactive medications. As per VA policy, I called the VA pharmacy line every month to get my prescriptions refilled. Within days of the call, the drugs were most commonly delivered to my parents’ house, as my financial and housing situation was so unstable that I didn’t know where I’d be living from week to week.

At both the Manhattan and Ann Arbor VA medical centers, I had requested counseling for ADHD, my original diagnosis. At both facilities, I was told the VA didn’t have anyone who specializes in ADHD. When I asked for a referral, I was told they could not do that either.

At the Ann Arbor VA, I made multiple requests to see a counselor for depression and anxiety. VA policies required me to complete a month-long group program before I could see a counselor individually, which I did not feel comfortable doing. This was the same policy that played a role in the suicide death of Army Veteran Daniel Somers, who became one of the original whistleblowers on the negligence occurring at the Phoenix VA Medical Center in 2013. His parents have been fighting to have this policy changed since his death. It wasn’t fixed and it harmed me.

When I asked again, I was told that without going through the group program the only other option was telehealth, in which I would speak to a counselor through a TV screen. I passed on that also. The idea of talking to a screen at the Ann Arbor VA was ridiculous, as the psychologist was likely on the other side of the wall. After multiple denials of counseling and failed attempts by my primary care doctor as she advocated inside the bureaucracy for me, I gave up asking.

Closure

The following is the transcript from my final meeting with my former psychiatrist at the Ann Arbor VA Medical Center on May 29, 2019.

Prescriber: How’s your family?

Derek: A lot better when I’m not being an asshole and blowing up on them.

Derek: I want to talk to you about my diagnosis even going back to my ADHD diagnosis: because originally when I came in I was diagnosed as a kid with ADHD, or ADD then, and then as an adult in 2014 when I was taking classes at Fordham I had gotten behind in a couple classes, I went to a psychiatrist because I remembered I got diagnosed as a kid, I got put on Adderall, and then when I transferred over to the VA, the diagnosis rolled right over into the VA. We never looked at social circumstances of what was going on in my life during those times; so for childhood, I got bullied for 10 years, like daily tormented, spit on, kicked, beat up, every day for like close to ten years. So if that’s going on, it’s going to make it awfully difficult to pay attention to your math class. Then as an adult, when I was taking classes at Fordham, I got behind in the classes because I was excited about the technology company that I was starting.

Prescriber: When I first saw you, I am usually careful to try to make sure, to try to, um, um not to just take it at face value, to try to substantiate the diagnosis by going over symptoms. What did I write [now looking at notes on computer]. I said symptoms including being easily distractible, careless mistakes, avoidance of tasks requiring sustained mental effort, starting but not finishing tasks, difficulty organizing complex tasks, frequent fidgeting, feelings of inner restlessness, those are all symptoms in the book of ADHD, they are also very subjective, you know… when it’s the kind of thing if we’re inclined to diagnose so that we can go down the list and you can say yeah, I have this symptom, if we’re inclined not to you can say well not so much. That it’s not in any way an exact science. There’s no real test for it. So it’s just a clinical diagnosis, just based on self-reporting of symptoms.

Derek: Because I was on the Adderall, that drug actually acted as a waterfall. I went from Adderall to Ambien because I couldn’t sleep because I was on the stimulant, so I’ve got insomnia; and then I’ve got anxiety, so then I’m on Gabapentin; and then I’m on Viagra because it’s a side effect of the Adderall; and then ultimately Zoloft for depression. It started with Adderall and all these other drugs were really treating disorders that were created because of the Adderall, not that I had any underlying condition.

Prescriber: And it did you more harm than good.

Derek: Can we edit in my records that it was misdiagnosed, or can we get it removed from my records?

Prescriber: I can’t get it removed, but I can put in a note in that we want to question that. Did I, was the symptoms I just listed, were those not accurate, or do, do you think you were just like embellishing the amount of difficulty you were having with those things, that it wasn’t really that bad? Because those would qualify for the diagnosis.

Derek: We never really addressed the core issues which put me on the drugs in the first place, which were social. That I was bullied and that I was ultimately starting a tech company. The real direction I should have gotten in New York should have been “drop the classes, start your company”; not “here’s a stimulant because you’re distracted from your classes.”

Prescriber: There’s other diagnosis, but there’s also generalized anxiety, what do we think about that?

Derek: Adderall. I was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder and I shouldn’t have been on a stimulant when I’m walking around with panic attacks.

Prescriber: You never had the panic attacks other than when you were on the stimulant?

Derek: Correct.

He stares at his screen as a clock audibly ticks off the sixteen seconds of silence that pass.

Prescriber: You want me to say, we think in retrospect you think it was misdiagnosed. I’ll say that.

Acknowledging the Suicide Epidemic at VA Medical Centers

At my second-to-last appointment with my former prescriber, he volunteered: “I’ve never had a patient who has had as many issues with these medications as you.” I replied: “Maybe I’m just the one that came back.”

In the spring of 2018, at the same time I was suffering with acute antidepressant withdrawal, I attended a suicide awareness walk, hosted in the parking lot of the Ann Arbor VA Medical Center. While there, I met Lauren Bowen, the walk’s organizer. Through resilience, desperation and anger, and knowing what had happened to her family was not right, she created this walk in honor of her husband, who’d killed himself two years earlier, less than 10 miles from the same VA Medical Center.

Through conversations with Lauren and other veterans, I realized that her family’s story and my story were not an exception. They are the rule. A June 2019 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report that sampled prescribing practices at five VA facilities found that only 15% of veterans were offered talk therapy in lieu of psychiatric drug treatments. Forty-one percent of veterans who were receiving mental health treatment at those facilities were prescribed drugs alone.

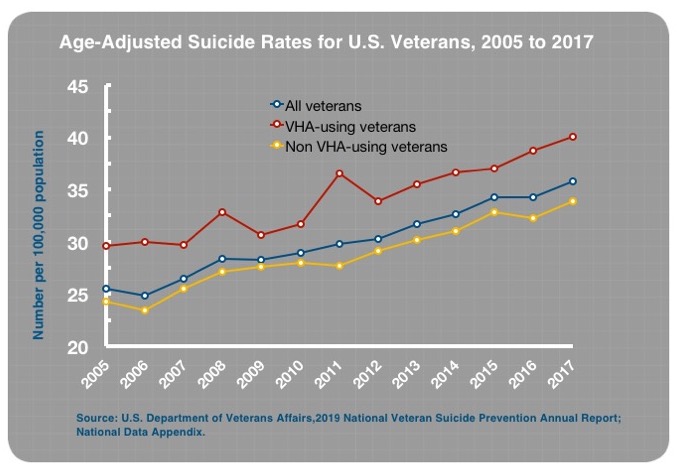

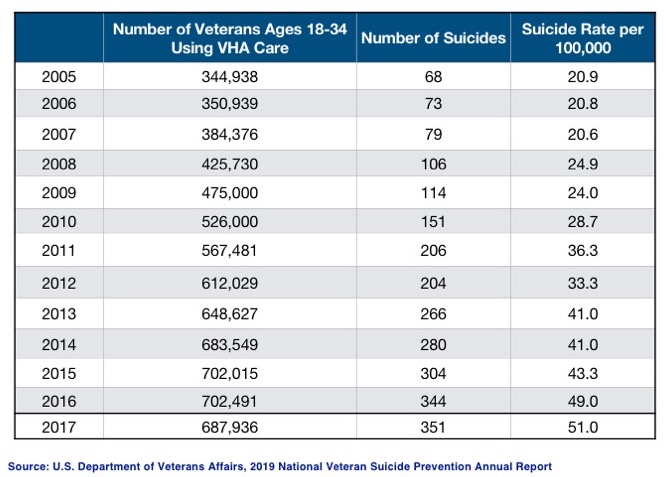

The following statistics were developed using the VA’s appendix data from their annual suicide reports, 2018-2019. They have not been published anywhere except at Mad in America, and have not been publicly disclosed by the VA:

- Suicide rates for veterans who use the VA are 32% higher than for veterans who do not use the VA.

- Between 2005 and 2017, there was a 144% increase in suicide rates for 18-to-34-year-old veterans who used the VA for their care.

- There was a fivefold increase in the actual number of suicides for that age group.

During the same period, suicide rates for 18-to-34-year-old veterans not using the VA for their care have increased by 57%, and in non-veterans in the same age group, by 30% — also concerning but certainly not as dramatic as the 144% increase for vets using the VA.

These statistics might sound shocking, but they shouldn’t. One does not need a PhD to know what is going on here. Multiple studies have confirmed that antidepressants can cause suicidal thoughts and behaviors. A meta-analysis of 702 randomized clinical studies found that suicide attempts were more than twice as high in those treated with an SSRI antidepressant compared to placebo.

That is why the FDA requires a “Black Box Warning” that states: “Antidepressants can cause suicidal thoughts and behaviors.” And when we consider the prescription rates of psychiatric drugs with Black Box Warnings to veterans inside and outside the VA, and then add in barriers to accessing counselors while allowing patients to go months and years being prescribed psychiatric medications without meeting with a counselor, the suicide rates should not surprise.

This is just one example of negligent prescribing and treatment practices, which have been codified into VA policy. We shouldn’t be looking for efficacy in treatment modalities, as is the current approach with evaluating mental health programs. Instead, we need to conduct forensic investigations to understand how we’ve become so efficient at what Lauren Bowen calls “stacking bodies.”

The report Robert Whitaker and I published the day before Veterans Day shows that veterans diagnosed with a mental health condition and who are treated by the VA have suicide rates that are double the rates for veterans who are also diagnosed but receive no treatment at all.

If you’re interested in learning what is defined as “treatment” in this data, so am I. The part of treatment that I am convinced is causing harm, based on experience and from a simple review of the data and FDA warnings, is prescribed antidepressants.

Resolution

I thought I had a diagnosable condition, and I thought I could get help for it. Based upon the treatment I received, I was wrong. Since I got off the cocktail of drugs I was prescribed, I’ve gone from unemployable, and homeless — I still don’t like saying it — to operating at a level I never have before. I’ve been properly motivated.

Seven months ago, I took my last dose of Zoloft, after a yearlong protracted war of withdrawal about which I, alongside millions of others, had received no warning.

Six months ago, I started working for Mad in America, where I help veterans, service members, and their families tell their stories and share their experiences with the DoD and VA mental health systems. These stories help others recover from prescribed harm while giving people the information necessary to make sound decisions regarding their treatment plans. (If you would like to tell your story, please email me at [email protected]). I know the benefit: These stories played a role in saving my life.

Four months ago, I delivered the keynote address at the Veterans of Foreign Wars National Memorial Service in front of over 2,000 people, where I spoke about my experience and the cause of the veteran suicide epidemic.

Three months ago, I co-founded WalkThere.org with old friends from SVA. As I went through my struggles of the past five years, I recognized that I was alone, I didn’t have a purpose, and I wasn’t taking care of myself. To solve for this isolation and to encourage healthy lifestyles, we host 20-minute weekly walks to help people become more connected with their friends, neighbors, and families.

Two months ago, the American Legion and the VFW passed national resolutions that I authored earlier in the year, urging Congress to investigate the role of antidepressants in causing veteran suicides.

And for the past year, I’ve been filming a documentary on my withdrawal and all of these efforts. When I figured out what had happened to me, I knew this might be a show to watch.

I thought the psychiatrists knew what they were doing. I thought the system was safe and the drugs had been well researched and worked as advertised. I was wrong. I wasn’t aware of the questionable circumstances that brought these drugs to market, as is described here by the law firm Baum, Hedlund, Aristei and Goldman.

Had I known what I know now, I never would have taken any of these drugs, and I absolutely would not have taken a role in which my outreach efforts to get veterans into mental health treatment might place thousands of lives at risk.

If I had concerns, I wouldn’t have gone to the VA for my care. But really, that wouldn’t have helped me, as this is not a VA problem. This is a mental health in America problem. The VA is a reflection of the “best practices” in the private sector.

There is a saying in the technology industry: “If you put a technology behind a good solution, it makes that solution exponentially more effective, but if you put a technology behind a bad solution, it makes that solution exponentially worse.”

In this case, the VA’s codification and streamlining of prescribing policies are that technology. The VA does what the private sector does, only more efficiently, which is why the VA disproportionately prescribes what we are now learning to be high-risk drugs.

Many experts within the military and veteran mental health-industrial complex are likely to say that much of what I am saying is wrong. That I’m making it up. That, as the VA said of the CBS expose, this “was not reviewed by independent scientists as most legitimate studies are.” They may also say, as referenced in the VA’s 2018 National Suicide Data Report, that veterans who use the VA are a higher needs, and therefore a higher risk, population. They’ll say this is why the suicide rates are higher for veterans who use the VA.

I say that some veterans who use the VA may have greater needs than non-VA using veterans; but this cannot explain 32% higher suicide rates at VA medical centers, or a 144% increase for 18-to-34-year-old veterans at the VA, or a fivefold actual increase in suicide among this age group at the VA.

I trusted the system. Not just the VA, or the mental health “system” nationally, but our government. I trusted the drug companies, the VA, the FDA, and most importantly Congress to have done their jobs and to have acted ethically.

This is a Crisis: #StoptheTrains

In Lauren’s words, every time her husband went to the VA, “he came home more discouraged, more broken and worse than before.” Until he didn’t come home.

I wrote this story not as an advocate or a leader in the veterans community but as a veteran. I’ve been fighting for change for nearly a year now and it has not been easy.

The victims and survivors of these harms have been left to suffer in isolation, with too few people fighting for them.

Democrats are afraid of digging into the suicides at the VA and with these drugs, as they are afraid of Republicans and the White House privatizing the VA. Some veterans organizations are afraid of digging into the suicides at the VA and these drugs for the same reason. While noble, the harm being inflicted is not worth the cost of not investigating.

Republicans are afraid of digging into the suicides at the VA and these drugs as they fear it may harm the President in an election year. (This situation is not President Trump’s fault. This crisis was inherited, and even if he knew it was a problem, he could not possibly have known its extent.)

Many mental health professionals are afraid of talking about the drugs and veteran suicides, as it comes with a possible admission that we might have unintentionally been causing harm.

Nearly all of those who could help do not want to touch this issue, as either they, their spouse, or their children are on these drugs, and feel as though a question about antidepressants is an attack on them and their decisions, which it is not.

This leaves me, Lauren, my friends Amanda Burrill, David Joslin, and Lindsay Church, all of whom shared their stories, alongside millions of others, who have been harmed or lost a loved one, on our own. We know that we are victims, but are left with few to fight for us.

I’ll continue to fight, as will my friends, but it shouldn’t be this way. This is a crisis. That means everything stops and this takes priority until we can stop the bleeding.

I hope Congress and the White House can be willing to investigate what is happening at the VA and inside DoD, as any further expansions of mental health programs inside or outside the government are likely to replicate what we are currently doing, and that is causing great harm.

I know. This is my story, but I am many.

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

Hi Derek,

Thank you for your sharing your trip through the system, and glad you came through it.

I found this part of your story very telling.

“A year ago, an old clinician friend who ran national veteran mental health programs for the University of Michigan asked me, nearly in tears, “Derek, you’re not a layperson, how did this happen to you?” Without hesitation, I replied, “It was the drugs.”

It is exactly the attitude that, those people, the laypersons are the ones who usually fall into the trap.

Only those suffer “illnesses” and receive “diagnosis”

They make a big mistake thinking of us as “laypersons”.

Perhaps they mean “sheep”

Report comment

It really shows the intense differentiation made by many or perhaps even most “professionals” between themselves (sane people) and their clients (insane people). It is this differentiation that makes it next to impossible for such professionals to be genuinely helpful to their own clients.

Report comment

And the irony is that, in reality, it is the “professionals” who are the DSM deluded (insane people), and us “laypersons” who have the science on our side (sane people).

Thanks for sharing your story, Derek. And you are correct, the antidepressants (and other psych drugs) are dangerous, mind altering drugs, that do destroy lives.

Report comment

Yes Steve.

Like people using that (MI) word in public or online

the old “there is no shame” is always used. It is like saying “there are different people” and adding “there is no shame in that”. Saying “there is no shame in that”, is a very condescending thing to say.

I used to frequent an Italian bar, during the day to relax and get my cuppa. A variety of folks sitting on the patio, chatting.

I have listened to quite a few psych students theorizing. Quite the amazing trip. 🙂

I usually carry duct tape for my mouth, should the need arise.

Report comment

Makes me wonder how Joe Adams is doing. He had two spectacular psychotic episodes about 60 years ago in which he suffered various delusions about being reincarnated religious fanatics of the early Reformation era. Eventually he became California’s Director of Mental Health (this was probably when the state was toying with alternate “mental health” treatments in the 1960’s, Adams having been working for Hoffer and Osmond when he had the hallucinatory episodes and received megavitamin B3 and C as treatment).

Report comment

I found Mad In America shortly after the site went up, have commented a number of times and related my experience, but perhaps this is a good time to share it again.

I am a US Navy Submarine Force veteran of the Cold War and Vietnam Conflicts. In the 1970s, before the diagnosis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder was developed, I was diagnosed with schizo-affective disorder by Veterans Affairs psychiatrists. After eight years of hostile and unsuccessful treatment with psychiatric drugs which severely damaged me both physically and emotionally to the point of ischemic strokes and suicidal ideation, I was extremely fortunate to recover completely within a few months. I had learned about Orthomolecular Therapy based on tissue mineral analysis of a hair sample and Creative Psychology through my own research and in 1982 was able to obtain a source of these treatments independent from the VA and at my own expense.

The cost of Orthomolecular Therapy and Creative Psychology is a fraction of that for biological psychiatry and the culture of life-long disability it creates.

My VA-assigned psychiatrist, who later rose to the presidency of the American Psychiatric Association, refused to acknowledge my use of Orthomolecular Therapy, the hair test results, or Creative Psychology and termed my recovery a “spontaneous remission”. Since 1982, I have lived a healthy, productive life, free of not only the need for psychiatric drugs, but all other prescription medicines as well.

I later learned that the lab I used, Analytical Research Labs, Phoenix AZ, recommended to me by friends in the nuclear field, was already a VA contractor. The VA was using tissue mineral analysis, not for therapeutic purposes, but forensic ones, to detect the presence of substances vets might have used in an attempt to self-medicate.

In 2007, concerned about the suicide rate of veterans diagnosed with PTSD, I began to attend a PTSD group at a VA CBOC Clinic. After only a few meetings where I shared my story with other veterans, I was taken aside by an unlicensed VA psychologist and VA psychiatrist, a graduate of a one-star foreign medical school. In a twenty minute interview they diagnosed me with paranoid schizophrenia, a rare and extremely disabling condition, and banned me from further participation in the PTSD group.

When this new diagnosis affected the renewal of my life insurance policy, I requested the medical records of my recovery in the 1980s. I discovered that all such mental health records in DVA VISN 1, in the 1978 to 1990 time period, had been spoliated. No records remain. I am convinced that thousands of veterans could have made recoveries similar to mine, with thousands of lives saved, had VA psychiatrists run studies on Orthomolecular Therapy and Creative Psychology instead of destroying all evidence of a veteran’s drug-free recovery and attempting to discredit him.

Report comment

Collectively, they need to protect something. One on one, if they had no support, they crumble.

Psychiatry has no emotional investment in anyone’s life.

However, if the majority collectively gathered to call them out, they could never survive.

Report comment

TERRIBLE ANXIETY

Q. Do Psychiatric Drugs cause Anxiety?

A. In my experience they can cause Terrible Anxiety.

Q. Is it possible to overcome this Anxiety?

A. Yes it definitely is.

Q. How?

A. In lots and lots of Normal Ways (and by carefully coming off the medication).

Report comment

Somatic Psychotherapist Peter Levine demonstrates PTSD Recovery

https://youtu.be/Oz8tnuXbNAY

Report comment

Thank you,

Powerful, very important and deeply moving.

Report comment

This is an outstanding report Derek driving home how deadly the medical model of drugs and labels are to veterans and the general population. As always in psychiatry the real causes of a person’s difficulties or distress etc are ignored and instead drugs and labels are pushed as happened to you with the label of “ADHD” and later the effects of the drug “finasteride”.

As you say, your story is not the exception, it is the rule and “The VA is a reflection of the “best practices” in the private sector.”

Yes, we all unfortunately trusted doctors, the system and government and found out the hard way how misplaced that trust was. It is stomach-turning to hear the media and other sources encouraging people to seek “help” in the mental health system when it is that very “help” that breaks people and drives them further into despair.

I commend you for your diligence, commitment and all your work and involvement in the ongoing fight to stop this harm and help save lives. Keep up the good work!

Report comment

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OziqRm6Hc4E

Report comment

This therapy combines elements of Sufism, yoga, martial arts and zen into a very effective package. It is warrior training for the battle of life.

Watch the film about the early years of George Gurdjieff available at many sites on line.

https://archive.org/details/GurdjieffMeetingsWithRemarkableMen

This is what I called “Creative Psychology” in my post above, a term coined by biochemist Robert S. DeRopp who was a student of Gurdjieff and wrote many books on the subject of personal growth, all very much worth reading, especially “The Master Game – Beyond the Drug Experience”

https://selfdefinition.org/psychology/Robert-S-De-Ropp-The-Master-Game.pdf

Report comment

Interesting Subvet,

I never heard of him, I will check it/him/them out.

Report comment